Walter Winchell: He Snooped to Conquer

If he is remembered, the journalist and radio man Walter Winchell evokes a few different types of memories. Baby boomers might recall the narrator of the 1959 series The Untouchables. Their children might have caught the HBO biopic Winchell that starred Stanley Tucci as the fedora-donning gossip columnist. Younger people likely won’t recognize the name Walter Winchell at all. But consider this: every time you guiltily click on a link promising a juicy scoop on a washed-up actor, Winchell is somewhere, smiling.

In his heyday, Winchell commanded a collective audience of about 50 million Americans — two-thirds of the adult population in the 1930s. As biographer Neal Gabler claims in American Heritage magazine, anyone walking the streets on a warm Sunday evening in any city in America at the time would hear Winchell’s staccato voice through successive open windows on their way, giving updates on the war in Europe or a famous couple who might be “infanticipating.”

Making and breaking celebrities and politicians in his syndicated columns and radio broadcasts, Winchell built a complicated legacy. Though he often leveraged his platform to give a voice to everyday Americans, Winchell’s lifelong quest for popularity became his own undoing.

A new PBS American Masters documentary, Walter Winchell: The Power of Gossip, offers viewers a new look at how, for better or for worse, Winchell created “infotainment.” The documentary tracks the gadfly’s rise during the Great Depression and his slow decline in the McCarthy era, with Whoopi Goldberg as narrator and Stanley Tucci reprising his role as Winchell.

Director Ben Loeterman says that he was drawn to Winchell’s story as a sort of explanation of the current state of news media: “I think understanding the origins of how news is shaped and delivered and the importance of story, that has become absolutely part of journalism today, started in that sense, I think, with Walter Winchell.”

Winchell’s career arc can be simply understood with his own words: “From my childhood, I knew what I didn’t want: I didn’t want to be cold, I didn’t want to be hungry, homeless, or anonymous.”

In his early years reporting Broadway gossip at Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic (a tabloid commonly called the “Porno-Graphic”), Winchell learned that “the way to become famous fast is to throw a brick at someone who is famous.” He quickly made enemies, namely the Schuberts, who banned him from their theaters. Winchell secured a hefty readership, though, with his euphemistic claims about Jazz Age New Yorkers. Soon enough, he was rubbing elbows with Ernest Hemingway, Al Capone, and plenty of others who feared and respected his power of the press. He regularly attended Manhattan’s Stork Club, where anyone who was anyone knew to find him.

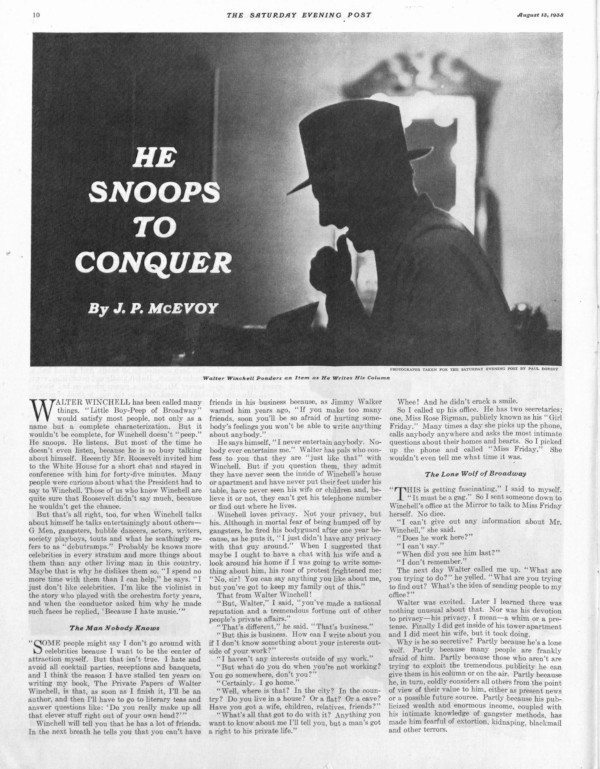

J.P. McEvoy turned a journalistic eye onto Winchell and his brand of “personal journalism,” writing the profile “He Snoops to Conquer” in this magazine in 1938. “Because he was fearless, talented, tireless and tormented by an unappeasable itch for success,” McEvoy wrote, “he arrived at his present peak — where he lives in a state of ingenuous surprise that he has arrived and a gnawing fear that he cannot remain.” Winchell was making about $300,000 a year at the time, between movies, radio, and his column at the Daily Mirror, which was syndicated to thousands of papers across the country. He had become famous for, among other things, coining provocative slang many called “New Yorkese.” H.L. Mencken, in The American Language, noted Winchell’s introduction of several words and phrases into the lexicon. Reno-vated (divorced), obnoxicated, Hard Times Square, intelligentleman. A young couple might be cupiding or “makin’ whoopee.”

Winchell’s reports weren’t limited to celebrity gossip, though. He was an early, outspoken critic of Nazism, taking shots at Hitler as a “homosexualist” called “Adele Hitler” (“he put a hand on a Hipler … ”) and regularly blasting antisemitic Nazi propaganda. When a German-American man named Fritz Kuhn began rallying Nazi sympathizers, first in the Friends of New Germany and later in the German-American Bund, Winchell found a nearer target for derision (“the SHAMerican”). Kuhn thought of himself as a sort of “American Führer,” organizing youth camps and rallies with the growing Bund in the ’30s. Right before more than 20,000 Nazis and Nazi sympathizers descended on Madison Square Garden in 1939 for George Washington’s birthday, Winchell tore into “the Ratzis … claiming G.W. to be the nation’s first Fritz Kuhn … There must be some mistake. Don’t they mean Benedict Arnold?” Winchell was delighted when Kuhn was sentenced to prison for embezzlement that year, writing about how the warden would be “the chief sufferer.”

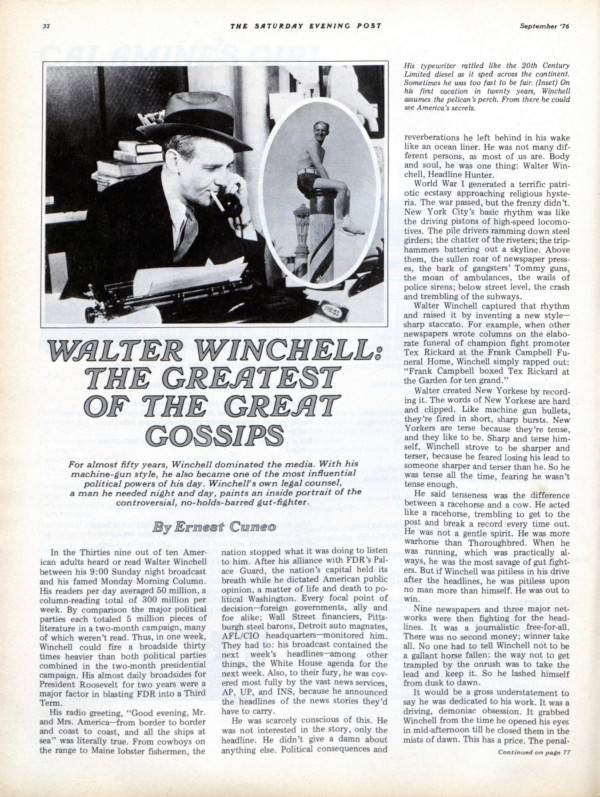

At the start of President Roosevelt’s first term, Winchell praised the president as “the nation’s new hero,” sparking a close relationship with the administration that would prove fruitful for both of them. Years later, Post editor and former Roosevelt liaison Ernest Cuneo wrote all about how prominently Winchell had figured into their strategy to get FDR a third term (“Look, Walter,” I wanted to say, “you are the Third Term campaign.”).

Winchell was taken with President Roosevelt — and perfectly happy to act as a patriotic mouthpiece for the New Deal and American intervention in the war — but after Roosevelt left office, the gossip reporter found himself politically stranded. In 1951, Winchell affronted African-American performer Josephine Baker when he failed to defend her allegations of racism at his beloved Stork Club. Then, in 1954, he frustrated public health efforts by incorrectly announcing on his broadcast that a new polio immunization “may be a killer,” contributing to a dangerous anti-vaccination backlash. Winchell was really sunk, however, after he aligned himself closely with Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn.

“If he thought there was a star he could hitch himself to,” Loeterman says, “that was more important than the politics or any of the rest of it.”

Winchell transferred his disdain for Nazism into the anti-Communist witch hunts of the ’50s. He had vocalized his opposition to communism throughout his career, but McCarthy and Cohn made him an honorary member of a new — doomed — club. As Gabler put it, “he would lose because his populism had transmogrified into something cruel and unmanageable, just as his detractors had charged. Once a lovable rogue, Walter Winchell had become detestable.” He had brief stints on television in the ’50s, but nothing stuck. Winchell’s newspaper and radio routines were things of the past, and he had cultivated too much public distrust.

Although he faded from the public eye, Winchell’s mark was already made: the “welding” of news and entertainment. Two years after his death, People magazine was launched, and no shortage of commentators and gossips have haunted our screens and papers since. Kurt Andersen wrote in the Times about the evolution of Winchell’s personal journalism, “As star columnists leveraged their columns to accumulate personal celebrity and their personal celebrity to generate more readers, the market for their sort of journalism grew.”

If Winchell isn’t remembered, then he ought to be, if only so that we can more clearly understand that clickbait has a snappy, five-foot-seven predecessor who was one of the most famous men of his time.

Featured image taken by Paul Dorsey, The Saturday Evening Post, August 13, 1938

Good News About Bad News

“I’ve got some good news and some bad news.”

You’ve undoubtedly said that before. Whether you’re a parent, a teacher, a doctor, or a writer trying to explain a missed deadline, you had to deliver information — some of it positive, some of it not — and opened with this two-headed approach.

But which piece of information should you introduce first? Should the good news precede the bad? Or should the happy follow the sad?

As someone who finds himself delivering mixed news more often than he should or wants to, I’ve always led with the positive. My instinct has been to spread a downy duvet of good feeling to cushion the coming hammerblow.

My instinct, alas, has been dead wrong.

To understand why, let’s switch perspectives — from me to you. Suppose you’re on the receiving end of my mixed news, and after my “I’ve got some good news and some bad news” windup, I append a question: “Which would you like to hear first?”

Think about that for a moment.

Chances are, you opted to hear the bad news first. Several studies over several decades have found that roughly four out of five people prefer to begin with a loss or negative outcome and ultimately end with a gain or positive outcome, rather than the reverse. Our preference, whether we’re a patient getting test results or a student awaiting a mid-semester evaluation, is clear: bad news first, good news last.

But as news givers, we often do the reverse. Delivering that harsh performance review feels unsettling, so we prefer to ease into it, to demonstrate our kind intentions and caring nature by offering a few spoonfuls of sugar before administering the bitter medicine. Sure, we know that we like to hear the bad news first. But somehow we don’t understand that the person sitting across the desk, wincing at our two-headed intro, feels the same. She’d rather get the grimness out of the way and end the encounter on a more redeeming note. As two of the researchers who’ve studied this issue say, “Our findings suggest that the doctors, teachers, and partners … might do a poor job of giving good and bad news because they forget for a moment how they want to hear news when they are patients, students, and spouses.”

We blunder — I blunder — because we fail to understand the final principle of endings: Given a choice, human beings prefer endings that elevate. The science of timing has found — repeatedly — what seems to be an innate preference for happy endings. We favor sequences of events that rise rather than fall, that improve rather than deteriorate, that lift us up rather than bring us down. And simply knowing this inclination can help us understand our own behavior and improve our interactions with others.

For example, social psychologists Ed O’Brien and Phoebe Ellsworth of the University of Michigan wanted to see how endings shaped people’s judgment. So they packed a bag full of Hershey’s Kisses and headed to a busy area of the Ann Arbor campus. They set up a table and told students they were conducting a taste test of some new varieties of Kisses that contained local ingredients.

People sidled up to the table, and a research assistant, who didn’t know what O’Brien and Ellsworth were measuring, pulled a chocolate out of the bag and asked a participant to taste it and rate it on a 0-to-10 scale.

Then the research assistant said, “Here is your next chocolate,” gave the participant another candy, and asked her to rate that one. Then the experimenter and her participant did the same thing again for three more chocolates, bringing the total number of candies to five. (The tasters never knew how many total chocolates they would be sampling.)

The crux of the experiment came just before people tasted the fifth chocolate. To half the participants, the research assistant said, “Here is your next chocolate.” But to the other half of the group, she said, “Here is your last chocolate.”

The very best endings are not always happy in the traditional sense. Often … they’re bitter sweet.

The people informed that the fifth chocolate was the last — that the supposed taste test was now ending — reported liking that chocolate much more than the people who knew it was simply next. In fact, people informed that a chocolate was last liked it significantly more than any other chocolate they’d sampled. They chose chocolate number five as their favorite chocolate 64 percent of the time (compared with the “next” group, which chose that chocolate as their favorite 22 percent of the time). “Participants who knew they were eating the final chocolate of a taste test enjoyed it more, preferred it to other chocolates, and rated the overall experience as more enjoyable than other participants who thought they were just eating one more chocolate in a series.”

Screenwriters understand the importance of endings that elevate, but they also know that the very best endings are not always happy in the traditional sense. Often, like a final chocolate, they’re bittersweet. “Anyone can deliver a happy ending — just give the characters everything they want,” says screenplay guru Robert McKee. “An artist gives us the emotion he’s promised … but with a rush of unexpected insight.” That often comes when the main character finally understands an emotionally complex truth. John August, who wrote the screenplay for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and other films, argues that this more sophisticated form of elevation is the secret to the success of Pixar films such as Up, Cars, and the Toy Story trilogy.

“Every Pixar movie has its protagonist achieving the goal he wants only to realize it is not what the protagonist needs. Typically, this leads the protagonist to let go of what he wants (a house, the Piston Cup, Andy) to get what he needs (a true yet unlikely companion, real friends, a lifetime together with friends).” Such emotional complexity turns out to be central to the most elevated endings.

Researchers Hal Hershfield and Laura Carstensen teamed up with two other scholars to explore what makes endings meaningful. In one of their studies, the researchers approached Stanford seniors on graduation day to survey them about how they felt. To one group, they gave the following instructions: “Keeping in mind your current experiences, please rate the degree to which you feel each of the following emotions,” and then gave them a list of 19 emotions. To the other group, they added one sentence to the instructions to raise the significance that something was ending: “As a graduating senior, today is the last day that you will be a student at Stanford. Keeping that in mind, please rate the degree to which you feel each of the following emotions.”

The researchers found that at the core of meaningful endings is one of the most complex emotions humans experience: poignancy, a mix of happiness and sadness. For graduates and everyone else, the most powerful endings deliver poignancy because poignancy delivers significance. One reason we overlook poignancy is that it operates by an upside-down form of emotional physics. Adding a small component of sadness to an otherwise happy moment elevates that moment rather than diminishes it. “Poignancy,” the researchers write, “seems to be particular to the experience of endings.” The best endings don’t leave us happy. Instead, they produce something richer — a rush of unexpected insight, a fleeting moment of transcendence, the possibility that by discarding what we wanted we’ve gotten what we need.

Endings offer good news and bad news about our behavior and judgment. I’ll give you the bad news first, of course. Endings help us evaluate and record our experiences, but they can sometimes twist our memory and cloud our perception by overweighting final moments and neglecting the totality.

But endings can also be a positive force. They can help energize us to reach a goal. They can help us edit the nonessential from our lives. And they can help us elevate — not through the simple pursuit of happiness but through the more complex power of poignancy. Closings, conclusions, and culminations reveal something essential about the human condition: In the end, we seek meaning.

From When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing by Daniel H. Pink, published by Riverhead. An imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Daniel H. Pink.

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Numbed by Media: Newspaper Reading as a Dissipation

Over 16,000 newspapers were feeding America’s hunger for news in 1900. People were becoming better informed, but Post editors worried the constant exposure to violence, injustice, and scandal in the papers was making Americans incapable of outrage.

The first peril of careless newspaper reading is that of being morally hardened by constant contact with the physical and spiritual evils of the world, without being called upon to any action with regard to them.

It requires a notable degree of moral culture to keep from becoming “used to” such things; and there are few things worse for us than to grow accustomed to men’s sufferings and their sins, so that these no longer evoke pity, or indignation, or any other emotion in us.

The great minds are those which show the least disposition to become familiar with wrong, so as not to feel indignation every time they see it. They have a moral freshness which is our right and normal condition. They never “get used to” good or evil.

It is very hard for us to keep this freshness of moral impression in our daily contact with what the newspaper tells us of the world’s evil. It is even harder not to be deceived as to the comparative weight of evil and goodness in the world. The newsgatherer is drawn naturally to the former.

—“Newspaper Reading as a Dissipation,” Editorial by Robert Ellis Thompson, March 11, 1899

This article is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Americans Should Not Fear the Media

This past year was a landmark year for ordinary citizens in the news. Without the hurricane survivors, student protestors, mass shooting victims, and sexual abuse survivors who agreed to speak to reporters, our understanding of some of the most important issues of the day would be murky at best. By giving firsthand accounts of what happened on the ground — or on the casting couch — before reporters arrived at the scene, citizen sources perform an important public service. But behind every citizen we see in the news is another story — about their interaction with journalists and the repercussions of their decision to go public — that audiences rarely know much about.

Occasional glimpses behind the scenes are telling — and troubling. A hurricane survivor bawls out a journalist in a video that goes viral. Student gun-control advocates later face cyberharassment and conspiracy theories.

I’ve spent the last 10 years interviewing ordinary people about what it feels like to become the focus of news attention. I spoke to victims, heroes, witnesses, criminals, voters, experts, and more. All were private citizens. Their stories raise important questions for journalists and audiences, and for anyone considering speaking to a reporter. They also hold important clues about media trust at a moment when online disinformation is a major concern, and public confidence in mainstream news has reached an alarming low.

Journalists control how people’s stories are told to the public: what is included, how it is framed, and who is cast as the hero or the bad guy.

Understanding how non-journalists see the news media is an essential step in rebuilding public trust. One of the most striking lessons I learned from speaking to citizen news sources is how differently they tend to see journalists from how journalists tend to see themselves. My interviewees mostly thought of journalists not primarily as citizens’ defenders against powerful people and institutions, but as powerful people and institutions in their own right.

Journalists seem powerful to ordinary citizens for several interrelated reasons. The first is that journalists have a much larger audience than most people can reach through their social networks. Journalists can be gatekeepers to publicity and fame. But, most importantly, they control how people’s stories are told to the public: what is included, how it is framed, and who is cast as the hero or the bad guy.

Those decisions can have favorable or destructive consequences for the people they are reporting about — consequences that are magnified online. And yet, journalists seem to dole out those benefits or damages pretty cavalierly.

To many non-journalists, the news media’s relationship to the public seems fundamentally unequal, and potentially exploitative. Ordinary people who make the news experience that inequality firsthand. Even when journalists are compassionate, friendly, and professional, the structure of the encounter usually feels lopsided.

News subjects are usually more deeply invested and involved in newsworthy events than journalists. That’s why journalists seek them out. Subjects were there when the shots rang out or were on intimate terms with the deceased. They feel these are their stories.

And yet, journalists swoop in to gather what they need in a process that feels both invasive and mysterious. Often, people decide to speak to reporters because they see it as an opportunity to address the public about an important issue, or enjoy the benefits of publicity. But the price of inclusion in the news product is control over how their story is told. Journalists quickly move on to the next story. Subjects stay on the ground to clean up the rubble and bury the dead — and manage the impact of the news coverage on their lives.

At a time when everything is googleable, that impact is exacerbated by online publication in two main ways. The first is that mainstream news articles perform very well in online searches. Old articles, once relegated to basement archives, now pop right up when you search for someone’s name and stay there possibly forever. Speaking to the press about sexual harassment, for example, was always risky. Today it brings with it the prospect that anyone googling you in the future — employers, landlords, students, dates — will know about that episode in your life.

Cyberabuse is the other big problem. Studies find online harassment is increasingly common. The controversial issues and breaking news events that thrust ordinary citizens into the media spotlight tend to trigger strong sentiment. That has long been true, but, before the internet, it took more effort to contact people named in news stories. Today we consume news on the same devices we can use to contact those people. Many of my interviewees reported receiving social media messages from strangers — some supportive, some abusive — as well as seeing themselves become fodder for online commentary. Not all news stories trigger digital blowback, but I have found that controversial stories almost always do.

Despite the unforeseen consequences of their news appearances, most of my interviewees liked the reporters who wrote about them and felt they had benefited from the experience overall. But in most cases, that one positive experience appeared to do little to shake their negative attitudes toward the news media as a whole.

For example, a woman I’ll call Ruby, who had survived a gang shooting in Harlem, described the reporter who had interviewed her as “gutsy, friendly, honest.” But she thought he was the exception to the rule.

That reporters don’t always take unethical advantage of their position was a welcome discovery to some interviewees, but it was not nearly as salient as the feeling that they always could.

Caty (another pseudonym) summed up the sentiment well. A New York City restaurant owner, she believed her business, threatened with closure, had been saved by a sympathetic news article. On the surface, hers was a classic story of a journalist defending a citizen against an oppressive bureaucracy. Caty was grateful to the newspaper and the reporter. But our interview ended like this:

Q: Is there anything else you think I should know?

Caty: My biggest thing is, the press has so much power. They should know the power they hold, and they should be ethical. The doctor is there to take care of a patient, over anything else. The press is there to tell the truth. And that’s been lost.

To many of the people I have interviewed, like Caty, the news media was a powerful entity that hulked over the citizenry. It was supposed to look out for citizens but often took advantage of them instead.

In short, it was a bully.

That helps explain why, shocking as it may seem, people may find it cathartic to see a news subject lash out at a reporter, whether it’s a hurricane survivor, a congressional candidate … or even the president of the United States.

The idea that many citizens feel like David to the news media’s Goliath may be hard for journalists to stomach or believe. It is the exact opposite of how journalists normally think of themselves. In their view, the news media works and fights on behalf of the people. Journalists are David, facing down the powers that be in the name of the citizens.

And yet, if news institutions want to regain long-waning public trust, they need to address the widespread perception that the news media is more interested in serving itself than the public. They would do well to highlight not just their accuracy, but their care, empathy, and ability to listen to the little guy.

This article is featured in the January/February 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.