Heroes of Vietnam: Death in the Ia Drang Valley

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

Originally published January 28, 1967.

Spc. 4/c Jack P. Smith was a supply clerk in the 1st Air Cavalry Division in South Vietnam. Smith’s company — Charlie Company of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry (Regiment) — had never been in action, and Smith, who was 20 years old, had come to believe that it never would. “We thought we were a sham,” Smith recalls today. “We dug and walked and looked for an enemy who was never there.”

In November 1965, units of the 7th Cavalry began to make the first American penetration in force of a communist stronghold near the Cambodian border. On November 15, Smith’s battalion was ordered in to help the 1st Battalion, which was meeting strong resistance. This was the beginning of the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, the first pitched battle fought by American soldiers in the war for Vietnam, and the bloodiest engagement of the long and divisive struggle.

After a day of marching into the jungle, Smith and the 500 other men of the 2nd Battalion came upon a clearing, known on the maps as X‑ray, where the 1st Battalion was fighting. The names of the soldiers have been changed, but in all other respects, this is what happened.

The 1st Battalion had been fighting continuously for three or four days, and I had never seen such filthy troops. Some of them had blood on their faces from scratches and from other guys’ wounds. Some had long rips in their clothing where shrapnel and bullets had missed them. They all had that look of shock. They said little, just looked around with darting, nervous eyes.

Whenever I heard a shell coming close, I’d duck, but they’d keep standing. After three days of constant bombardment, you get so you can tell from the sound how close a shell is going to land within 50 to 75 feet. There were some wounded lying around, bandaged up with filthy shirts and bandages, smoking cigarettes or lying in a coma with plasma bottles hanging above their stretchers.

Late that morning, the Cong made a charge. About 100 of them jumped up and made for our lines, and all hell broke loose. The people in that sector opened up with everything they had. Then a couple of our Skyraiders came in. One of them dropped a lot of stuff that shimmered in the sun like green confetti. It looked like a ticker-tape parade, but when the things hit the ground, the little pieces exploded. They were anti-personnel charges. Every one of the gooks was killed. Another group on the other side almost made it to the lines. There weren’t enough GIs there, and they couldn’t shoot them down fast enough. A plane dropped some napalm bombs just in front of the line. I couldn’t see the gooks. But I could hear them scream as they burned. A hundred men dead, just like that.

My company, Charlie Company, took over its sector of the battalion perimeter and started to dig in. At three o’clock another attack came, but it never amounted to anything. I didn’t get any sleep that night. There was continuous firing from one until four, and it was as bright as day with the flares lighting up the sky.

The next morning, the order came for us to move out. I guess our commanders felt the battle was over. The three battalions of PAVN (People’s Army of Vietnam — the North Vietnamese) were destroyed. There must have been about 1,000 rotting bodies out there, starting about 20 feet from us and surrounding the giant circle of foxholes. As we left the perimeter, we walked by them. Some of them had been lying out there for four days. There are more ants in Vietnam than in any place I have ever seen.

We were being withdrawn to Landing Zone Albany, some 6 miles away, where we were to be picked up by helicopter. About noon the column stopped and everybody flopped on the ground. It turned out that our reconnaissance platoon had come upon four sleeping PAVN who had claimed they were deserters. They said that there were three or four snipers in the trees up ahead — friends of theirs who did not want to surrender.

The head of the column formed by our battalion was already in the landing zone, which was actually only 30 yards to our left. But our company was still in the woods and elephant grass. I dropped my gear and my ax, which was standard equipment for supply clerks like me. We used them to cut down trees to help make landing zones for our helicopters. The day had grown very hot. I was about one-quarter through a smoke when a few shots cracked at the front of the column.

I flipped my cigarette butt, lay down, and grabbed my M-16. The fire in front was still growing. Then a few shots were fired right behind me. They seemed to come from the trees. There was firing all over the place now, and I was getting scared. A bullet hit the dirt a foot to my side, and some started whistling over my head.

This wasn’t the three or four snipers we had been warned about. There were over 100 North Vietnamese snipers tied in the trees above us — so we learned later — way above us, in the top branches. The firing kept increasing.

Our executive officer (XO) jumped up and said, “Follow me, and let’s get the hell out of here.” I followed him, along with the rest of the headquarters section and the 1st Platoon. We crouched and ran to the right toward what we thought was the landing zone. But it was only a small clearing — the L.Z. was to our left. We were running deeper into the ambush.

The fire was still increasing. We were all crouched as low as possible, but still keeping up a steady trot, looking from side to side. I glanced back at Richards, one of the company’s radio operators. Just as I looked back, he moaned softly and fell to the ground. I knelt down and looked at him, and he shuddered and started to gurgle deep in his stomach. His eyes and tongue popped out, and he died. He had a hole straight through his heart.

I had been screaming for a medic. I stopped. I looked up. Everyone had stopped. All of a sudden all the snipers opened up with automatic weapons. There were PAVN with machine guns hidden behind every anthill. The noise was deafening.

Then the men started dropping. It was unbelievable. I knelt there staring as at least 20 men dropped within a few seconds. I still had not recovered from the shock of seeing Richards killed, but the jolt of seeing men die so quickly brought me back to life. I hit the dirt fast. The XO was to my left, and Wallace was to my right, with Burroughs to his right. We were touching each other lying there in the tall elephant grass.

Men all around me were screaming. The fire was now a continuous roar. We were even being fired at by our own guys. No one knew where the fire was coming from, and so the men were shooting everywhere. Some were in shock and were blazing away at everything they saw or imagined they saw.

The XO let out a low moan, and his head sank. I felt a flash of panic. I had been assuming that he would get us out of this. Enlisted men may scoff at officers back in the billets, but when the fighting begins, the men automatically become very dependent upon them. Now I felt terribly alone.

The XO had been hit in the small of the back. I ripped off his shirt and there it was: a groove to the right of his spine. The bullet was still in there. He was in a great deal of pain, so a rifleman named Wilson and I removed his gear as best we could, and I bandaged his wound. It was not bleeding much on the outside, but he was very close to passing out.

Just then Wallace let out a “Huh!” A bullet had creased his upper arm and entered his side. He was bleeding in spurts. I ripped away his shirt with my knife and did him up. Then the XO screamed: A bullet had gone through his boot, taking all his toes with it. He was in agony and crying. Wallace was swearing and in shock. I was crying and holding on to the XO’s hand to keep from going crazy.

The grass in front of Wallace’s head began to fall as if a lawnmower were passing. It was a machine gun, and I could see the vague outline of the Cong’s head behind the foot or so of elephant grass. The noise of firing from all directions was so great that I couldn’t even hear a machine gun being fired three feet in front of me and one foot above my head.

As if in a dream, I picked up my rifle, put it on automatic, pushed the barrel into the Cong’s face and pulled the trigger. I saw his face disappear. I guess I blew his head off, but I never saw his body and did not look for it.

Wallace screamed. I had fired the burst pretty close to his ear, but I didn’t hit him. Bullets by the thousands were coming from the trees, from the L.Z., from the very ground, it seemed. There was a huge thump nearby. Burroughs rolled over and started a scream, though it sounded more like a growl. He had been lying on his side when a grenade went off about three or four feet from him. He looked as though someone had poured red paint over him from head to toe.

After that everything began getting hazy. I lay there for several minutes, and I think I was beginning to go into shock. I don’t remember much.

The amazing thing about all this was that from the time Richards was killed to the time Burroughs was hit, only a minute or two had elapsed. Hundreds of men had been hit all around us, and the sound of men screaming was almost as loud as the firing.

The XO was going fast. He told me his wife’s name was Carol. He told me that if he didn’t make it, I was to write her and tell her that he loved her. Then he somehow managed to crawl away, saying that he was going to organize the troops. It was his positive decision to do something that reinforced my own will to go on.

Then our artillery and air strikes started to come in. They saved our lives. Just before they started, I could hear North Vietnamese voices on our right. The PAVN battalion was moving in on us, into the woods. The Skyraiders were dropping napalm bombs a hundred feet in front of me on a PAVN machine-gun complex. I felt the hot blast and saw the elephant grass curling ahead of me. The victims were screaming — some of them were our own men who were trapped outside the wood line.

At an altitude of 200 feet, it’s difficult to distinguish one soldier from another. It’s unfortunate and horrible, but most of the battalion’s casualties in the first hour or so were from our own men, firing at everything in sight.

No matter what you did, you got hit. The snipers in the trees just waited for someone to move, then shot him. I could hear the North Vietnamese entering the woods from our right. They were creeping along, babbling and arguing among themselves, calling to each other when they found a live GI. Then they shot him.

I decided that it was time to move. I crawled off to my left a few feet, to where Sgt. Moore and Thompson were lying. Sgt. Moore had been hit in the chest three times. He was in pain and sinking fast. Thompson was hit only lightly in the leg. I asked the sergeant to hold my hand. He must have known then that he was dying, but he managed to assure me that everything would be all right.

I knew there wasn’t much chance of that. This was a massacre, and I was one of a handful not yet wounded. All around me, those who were not already dead were dying or severely wounded, most of them hit several times. I must have been talking a lot, but I have no idea what I was saying. I think it was, “Oh God, Oh God, Oh God,” over and over. Then I would cry. To get closer to the ground, I had dumped my gear, including the ax I had been carrying, and I had lost my rifle, but that was no problem. There were weapons of every kind lying everywhere.

Sgt. Moore asked me if I thought he would make it. I squeezed his hand and told him sure. He said that he was in a lot of pain, and every now and then he would scream. He was obviously bleeding internally quite a bit. I was sure that he would die before the night. I had seen his wife and four kids at Fort Benning. He had made it through World War II and Korea, but this little war had got him.

I found a hand grenade and put it next to me. Then I pulled out my first-aid pack and opened it. I still was not wounded, but I knew I would be soon.

At that instant, I heard a babble of Vietnamese voices close by. They sounded like little children, cruel children. The sound of those voices, of the enemy that close, was the most frightening thing I have ever experienced. Combat creates a mindless fear, but this was worse, naked panic.

A small group of PAVN was rapidly approaching. There was a heavy rustling of elephant grass and a constant babbling of high-pitched voices. I told Sgt. Moore to shut up and play dead. I was thinking of using my grenade, but I was scared that it wouldn’t get them all, and that they were so close that I would blow myself up too.

My mind was made up for me, because all of a sudden, they were there. I stuck the grenade under my belly so that even if I was hit the grenade would not go off too easily, and if it did go off I would not feel pain. I willed myself to stop shaking, and I stopped breathing. There were about 10 or 12 of them, I figure. They took me for dead, thank God. They lay down all around me, still babbling.

One of them lay down on top of me and started to set up his machine gun. He dropped his canister next to my side. His feet were by my head, and his head was between my feet. He was about six feet tall and pretty bony. He probably couldn’t feel me shaking because he was shaking so much himself.

I thought I was gone. I was trying like hell to act dead, however the hell one does that.

The Cong opened up on our mortar platoon, which was set up around a big tree nearby. The platoon returned the fire, killing about half of the Cong, and miraculously not hitting me. All of a sudden a dozen loud crumph sounds went off all around me. Assuming that all the GIs in front of them were dead, our mortar platoon had opened up with M-79 grenade launchers. The Cong jumped up off me, moaning with fear, and the other PAVN began to move around. They apparently knew the M-79. Then a second series of explosions went off, killing all the Cong as they got up to run. One grenade landed between Thompson’s head and Sgt. Moore’s chest. Sgt. Moore saved my life; he took most of the shrapnel in his side. A piece got me in the head.

It felt as if a white-hot sledge hammer had hit the right side of my face. Then something hot and stinging hit my left leg. I lost consciousness for a few seconds. I came out of it feeling intense pain in my leg and a numbness in my head. I didn’t dare feel my face: I thought the whole side of it had gone. Blood was pouring down my forehead and filling the hollow of my eyeglasses. It was also pouring out of my mouth. I slapped a bandage on the side of my face and tied it around my head. I was numbed, but I suddenly felt better. It had happened, and I was still alive.

I decided it was time to get out. None of my buddies appeared able to move. The Cong obviously had the mortar platoon pegged, and they would try to overrun it again. I was going to be right in their path. I crawled over Sgt. Moore, who had half his chest gone, and Thompson, who had no head left. Wilson, who had helped me with the XO, had been hit badly, but I couldn’t tell where. All that moved was his eyes. He asked me for some water. I gave him one of the two canteens I had scrounged. I still had the hand grenade.

I crawled over many bodies, all still. The 1st Platoon just didn’t exist anymore. One guy had his arm blown off. There was only some shredded skin and a piece of bone sticking out of his sleeve. The sight didn’t bother me anymore. The artillery was still keeping up a steady barrage, as were the planes, and the noise was as loud as ever, but I didn’t hear it anymore. It was a miracle I didn’t get shot by the snipers in the trees while I was moving.

came across Sgt. Barker, who stuck a .45 in my face. He thought I was a Cong and almost shot me. Apparently I was now close to the mortar platoon. Many other wounded men had crawled over there, including the medic Novak, who had run out of supplies after five minutes. Barker was hit in the legs. Caine was hurt badly too. There were many others, all in bad shape. I lay there with the hand grenade under me, praying. The Cong made several more attacks, which the mortar platoon fought off with 79s.

The Cong figured out that the mortar platoon was right by that tree, and three of their machine-gun crews crawled up and started to blaze away. It had taken them only a minute or so to find exactly where the platoon was; it took them half a minute to wipe it out. When they opened up, I heard a guy close by scream, then another, and another. Every few seconds someone would scream. Some got hit several times. In 30 seconds, the platoon was virtually nonexistent. I heard Lt. Sheldon scream three times, but he lived. I think only five or six guys from the platoon were alive the next day.

It also seemed that most of them were hit in the belly. I don’t know why, but when a man is hit in the belly, he screams an unearthly scream. Something you cannot imagine; you actually have to hear it. When a man is hit in the chest or the belly, he keeps on screaming, sometimes until he dies. I just lay there, numb, listening to the bullets whining over me and the 15 or 20 men close to me screaming and screaming and screaming. They didn’t ever stop for breath. They kept on until they were hoarse, then they would bleed through their mouths and pass out. They would wake up and start screaming again. Then they would die.

I started crying. Sgt. Gale was lying near me. He had been hit badly in the stomach and was in great pain. He would lie very still for a while and then scream. He would scream for a doctor, then he would scream for a medic. He pleaded with anyone he saw to help him, for the love of God, to stop his pain or kill him. He would thrash around and scream some more, and then lie still for a while. He was bleeding a lot. Everyone was. No matter where you put your hand, the ground was sticky.

Sgt. Gale lay there for over six hours before he died. No one had any medical supplies, no one could move, and no one would shoot him.

Several guys shot themselves that day. Schiff, although he was not wounded, completely lost his head and killed himself with his own grenade. Two other men, both wounded, shot themselves with .45s rather than let themselves be captured alive by the gooks. No one will ever know how many chose that way out, since all the dead had been hit over and over again.

All afternoon we could hear the PAVN, a whole battalion, running through the grass and trees. Hundreds of GIs were scattered on the ground like salt. Sprinkled among them like pepper were the wounded and dead Cong. The GIs who were wounded badly were screaming for medics. The Cong soon found them and killed them.

All afternoon there was smoke, artillery, screaming, moaning, fear, bullets, blood, and little yellow men running around screeching with glee when they found one of us alive, or screaming and moaning with fear when they ran into a grenade or a bullet. I suppose that all massacres in wars are a bloody mess, but this one seemed bloodier to me because I was caught in it.

About dusk a few helicopters tried landing in the L.Z., about 40 yards over to the left, but whenever one came within 100 feet of the ground, so many machine guns would open up on him that it sounded like a training company at a machine-gun range.

At dusk the North Vietnamese started to mortar us. Some of the mortars they used were ours that they had captured. Suddenly the ground behind me lifted up, and there was a tremendous noise. I knew something big had gone off right behind me. At the same time I felt something white-hot go into my right thigh. I started screaming and screaming. The pain was terrible. Then I said, “My legs, God, my legs,” over and over.

Still screaming, I ripped the bandage off my face and tied it around my thigh. It didn’t fit, so I held it as tight as I could with my fingers. I could feel the blood pouring out of the hole. I cried and moaned. It was hurting unbelievably. The realization came to me now, for the first time, that I was not going to live.

With hardly any light left, the Cong decided to infiltrate the woods thoroughly. They were running everywhere. There were no groupings of Americans left in the woods, just a GI here and there. The planes had left, but the artillery kept up the barrage.

Then the flares started up. As long as there was some light, the Cong wouldn’t try an all-out attack. I was lying there in a stupor, thirsty. God, I was thirsty. I had been all afternoon with no water, sweating like hell.

I decided to chance a cigarette. All my original equipment and weapons were gone, but somehow my cigarettes were still with me. The ends were bloody. I tore off the ends and lit the middle part of a cigarette.

Cupping it and blowing away the smoke, I managed to escape detection. I knew I was a fool. But at this stage I didn’t really give a damn. By now the small-arms fire had stopped almost entirely. The woods were left to the dead, the wounded, and the artillery barrage.

At nightfall I had crawled across to where Barker, Caine, and a few others were lying. I didn’t say a word. I just lay there on my back, listening to the swishing of grass, the sporadic fire and the constant artillery, which was coming pretty close. For over six hours now, shells had been landing within a hundred yards of me.

I didn’t move, because I couldn’t. Reaching around, I found a canteen of water. The guy who had taken the last drink from it must have been hit in the face, because the water was about one third blood. I didn’t mind. I passed it around.

About an hour after dark there was a heavy concentration of small-arms fire all around us. It lasted about five minutes. It was repeated at intervals all night long. Battalion Hq. was firing a protective fire, and we were right in the path of the bullets. Some of our men were getting hit by the rounds ricocheting through the woods.

I lay there shivering. At night in the highlands the temperature goes down to 50 or so. About midnight I heard the grass swishing. It was men, and a lot of them too. I took my hand grenade and straightened out the pin. I thought to myself that now at last they were going to come and kill all the wounded that were left. I was sure I was going to die, and I really did not care anymore. I did not want them to take me alive. The others around me were either unconscious or didn’t care. They were just lying there. I think most of them had quietly died in the last few hours. I know one — I did not recognize him — wanted to be alone to die. When he felt himself going, he crawled over me (I don’t know how), and a few minutes later I heard him gurgle and, I guess, die.

Then suddenly I realized that the men were making little whistling noises.

Maybe these weren’t the Cong. A few seconds later, a patrol of GIs came into view, about 15 guys in line, looking for wounded.

Everyone started pawing toward them and crying. It turned me into a babbling idiot. I grabbed one of the guys and wouldn’t let go. They had four stretchers with them, and they took the four worst wounded and all the walking wounded, about 10 or so, from the company. I was desperate, and I told the leader I could walk, but when Peters helped me to my feet, I passed out cold.

When I regained consciousness, they had gone, but their medic was left behind, a few feet from me, by a tree. He hadn’t seen me, and had already used his meager supply of bandages on those guys who had crawled up around the tree. His patrol said they would be back in a few hours.

I clung to the hope, but I knew damn well they weren’t coming back. Novak, who was one of the walking wounded, had left me his .45. I lost one of the magazines, and the only other one had only three bullets in it. I still had the hand grenade.

I crawled up to the tree. There were about eight guys there, all badly wounded. Lt. Sheldon was there, and he had the only operational radio left in the company. I couldn’t hear him, but he was talking to the company commander, who had gotten separated from us. Lt. Sheldon had been wounded in the thighbone, the kneecap, and the ankle.

Some time after midnight, in my half-conscious stupor, I heard a lot of rustling on both sides of the tree. I nudged the lieutenant, and then he heard it too. Slowly, everyone who could move started to arm himself. I don’t know who it was — it might even have been me — but someone made a noise with a weapon.

The swishing noise stopped immediately. Ten yards or so from us an excited babbling started. The gooks must have thought they had run into a pocket of resistance around the tree. Thank God, they didn’t dare rush us, because we wouldn’t have lasted a second. Half of us were too weak to even cock our weapons. As a matter of fact, there were a couple who did not have fingers to cock with.

Then a clanking noise started: They were setting up a machine gun right next to us. I noticed that some artillery shells were landing close now, and every few seconds they seemed to creep closer to us, until one of the Cong screamed. Then the babbling grew louder. I heard the lieutenant on the radio; he was requesting a salvo to bracket us. A few seconds later there was a loud whistling in the air and shells were landing all around us, again and again. I heard the Cong run away. They left some of their wounded a couple of yards from us, moaning and screaming, but they died within a few minutes.

Every half hour or so the artillery would start all over again. It was a long night. Every time, the shells came so close to our position that we could hear the shrapnel striking the tree a foot or so above our heads, and could hear other pieces humming by just inches over us.

All night long the Cong had been moving around killing the wounded. Every few minutes I heard some guy start screaming, “No, no, no, please,” and then a burst of bullets. When they found a guy who was wounded, they’d make an awful racket. They’d yell for their buddies and babble awhile, then turn the poor devil over and listen to him while they stuck a barrel in his face and squeezed.

About an hour before dawn the artillery stopped, except for an occasional shell. But the small-arms firing started up again, just as heavy as it had been the previous afternoon. The GIs about a mile away were advancing and clearing the ground and trees of Cong (and a few Americans too). The snipers, all around the trees and in them, started firing back.

When a bullet is fired at you, it makes a distinctive, sharp cracking sound. The firing by the GIs was all cracks. I could hear thuds all around me from the bullets. I thought I was all dried out from bleeding and sweating, but now I started sweating all over again. I thought, How futile it would be to die now from an American bullet. I just barely managed to keep myself from screaming out loud. I think some guy near me got hit. He let out a long sigh and gurgled.

Soon the sky began to turn red and orange. There was complete silence everywhere now. Not even the birds started their usual singing. As the sun was coming up, everyone expected a human-wave charge by the PAVN, and then a total massacre. We didn’t know that the few Cong left from the battle had pulled out just before dawn, leaving only their wounded and a few suicide squads behind.

When the light grew stronger, I could see all around me. The scene might have been the devil’s butcher shop. There were dead men all around the tree. I found that the dead body I had been resting my head on was that of Burgess, one of my buddies. I could hardly recognize him. He was a professional saxophone player with only two weeks left in the Army.

Right in front of me was Sgt. Delaney with both his legs blown off. I had been staring at him all night without knowing who he was. His eyes were open and covered with dirt. Sgt. Gale was dead too. Most of the dead were unrecognizable and were beginning to stink. There was blood and mess all over the place.

Half a dozen of the wounded were alive. Lord, who was full of shrapnel; Lt. Sheldon, with several bullet wounds; Morris, shot in the legs and arm; Sloan, with his fingers shot off; Olson, with his leg shot up and hands mutilated; and some guy from another company who was holding his guts from falling out.

Dead Cong were hanging out of the trees everywhere. The Americans had fired bursts that had blown some snipers right out of the trees. But these guys, they were just hanging and dangling there in silence.

We were all sprawled out in various stages of unconsciousness. My wounds had started bleeding again, and the heat was getting bad. The ants were getting to my legs.

Lt. Sheldon passed out, so I took over the radio. That whole morning is rather blurred in my memory. I remember talking for a long time with someone from Battalion Hq. He kept telling me to keep calm, that they would have the medics and helicopters in there in no time. He asked me about the condition of the wounded. I told him that the few who were still alive wouldn’t last long. I listened for a long time on the radio to chitchat between medevac pilots, Air Force jet pilots, and Battalion Hq. Every now and then I would call up and ask when they were going to pick us up. I’m sure I said a lot of other things, but I don’t remember much about it.

I just couldn’t understand at first why the medevacs didn’t come in and get us. Finally I heard on the radio that they wouldn’t land because no one knew whether or not the area was secure. Some of the wounded guys were beginning to babble. It seemed like hours before anything happened.

Then a small Air Force spotter plane was buzzing overhead. It dropped a couple of flares in the L.Z. nearby, marking the spot for an airstrike. I thought, My God, the strike is going to land on top of us. I got through to the old man — the company commander — who was up ahead, and he said that it wouldn’t come near us and for us not to worry. But I worried, and it landed pretty damn close.

There was silence for a while, then they started hitting the L.Z. with artillery, a lot of it. This lasted for a half hour or so, and then the small arms started again, whistling and buzzing through the woods. I was terrified. I thought, My Lord, is this never going to end? If we’re going to die, let’s get it over with.

Finally the firing stopped, and there was a ghastly silence. Then the old man got on the radio again and talked to me. He called in a helicopter and told me to guide it over our area. I talked to the pilot, directing him, until he said he could see me. Some of the wounded saw the chopper and started yelling, “Medic! Medic!” Others were moaning feebly and struggling to wave at the chopper.

The old man saw the helicopter circling and said he was coming to help us. He asked me to throw a smoke grenade, which I pulled off Lt. Sheldon’s gear. It went off, and the old man saw it, because soon after that I heard the guys coming. They were shooting as they walked along. I screamed into the radio, “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot,” but they called back and said they were just shooting PAVN.

Then I saw them: The 1st sergeant, our captain, and the two radio operators. The captain came up to me and asked me how I was.

I said to him: “Sorry, sir, I lost my —— ax.”

He said, “Don’t worry, Smitty, we’ll get you another one.”

The medics at the L.Z. cut off my boots and put bandages on me. My wounds were in pretty bad shape. You know what happens when you take raw meat and throw it on the ground on a sunny day. We were out there for 24 hours, and Vietnam is nothing but one big anthill.

I was put in a medevac chopper and flown to Pleiku, where they changed dressings and stuck all sorts of tubes in my arms. At Pleiku I saw Gruber briefly. He was a clerk in the battalion, and my Army buddy. We talked until they put me in the plane. I learned that Stern and Deschamps, close friends, had been found dead together, shot in the backs of their heads, executed by the Cong. Gruber had identified their bodies. Everyone was crying. Like most of the men in our battalion, I had lost all my Army friends.

I heard the casualty figures a few days later. The North Vietnamese unit had been wiped out — over 500 dead. Out of some 500 men in our battalion alone, about 150 had been killed, and only 84 returned to base camp a few days later. In my company, which was right in the middle of the ambush, we had 93 percent casualties — one half dead, one half wounded. Almost all the wounded were crippled for life. The company, in fact, was very nearly annihilated.

Our unit is part of the 7th Cavalry — Custer’s old unit. That day in the Ia Drang Valley, history repeated itself.

After a week in and out of field hospitals, I ended up at Camp Zama in Japan. They have operated on me twice. They tell me that I’ll walk again, and that my legs are going to be fine. But no one can tell me when I will stop having nightmares.

Postscript: Jack Smith did recover from his wounds and was sent back to his unit in Vietnam, where he served as a supply clerk from January to July 1966. He did not see any more action. He finished up his military career training recruits at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

—“Death in the Ia Drang Valley,” January 28, 1967

Carlos Bulosan’s ‘Freedom from Want’

In 1943, the Post commissioned four writers to craft an essay to accompany each of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, which had quickly come to represent America’s moral imperative during World War II. You can read the other three essays here.

Freedom from Want

Originally published March 6, 1943

If you want to know what we are, look upon the farms or upon the hard pavements of the city. You usually see us working or waiting for work, and you think you know us, but our outward guise is more deceptive than our history.

Our history has many strands of fear and hope, that snarl and converge at several points in time and space. We clear the forest and the mountains of the land. We cross the river and the wind. We harness wild beast and living steel. We celebrate labor, wisdom, peace of the soul.

When our crops are burned or plowed under, we are angry and confused. Sometimes we ask if this is the real America. Sometimes we watch our long shadows and doubt the future. But we have learned to emulate our ideals from these trials. We know there were men who came and stayed to build America. We know they came because there is something in America that they needed, and which needed them.

We march on, though sometimes strange moods fill our children. Our march toward security and peace is the march of freedom — the freedom that we should like to become a living part of. It is the dignity of the individual to live in a society of free men, where the spirit of understanding and belief exist; of understanding that all men are equal; that all men, whatever their color, race, religion or estate, should be given equal opportunity to serve themselves and each other according to their needs and abilities.

But we are not really free unless we use what we produce. So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves. It is only when we have plenty to eat — plenty of everything — that we begin to understand what freedom means. To us, freedom is not an intangible thing. When we have enough to eat, then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things. Then we are not merely living but also becoming a creative part of life. It is only then that we become a growing part of democracy.

We do not take democracy for granted. We feel it grow in our working together — many millions of us working toward a common purpose. If it took us several decades of sacrifices to arrive at this faith, it is because it took us that long to know what part of America is ours.

Our faith has been shaken many times, and now it is put to question. Our faith is a living thing, and it can be crippled or chained. It can be killed by denying us enough food or clothing, by blasting away our personalities and keeping us in constant fear. Unless we are properly prepared, the powers of darkness will have good reason to catch us unaware and trample our lives.

The totalitarian nations hate democracy. They hate us because we ask for a definite guaranty of freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom from fear and want. Our challenge to tyranny is the depth of our faith in a democracy worth defending. Although they spread lies about us, the way of life we cherish is not dead. The American Dream is only hidden away, and it will push its way up and grow again.

We have moved down the years steadily toward the practice of democracy. We become animate in the growth of Kansas wheat or in the ring of Mississippi rain. We tremble in the strong winds of the Great Lakes. We cut timbers in Oregon just as the wild flowers blossom in Maine. We are multitudes in Pennsylvania mines, in Alaskan canneries. We are millions from Puget Sound to Florida. In violent factories, crowded tenements, teeming cities. Our numbers increase as the war revolves into years and increases hunger, disease, death, and fear.

But sometimes we wonder if we are really a part of America. We recognize the mainsprings of American democracy in our right to form unions and bargain through them collectively, our opportunity to sell our products at reasonable prices, and the privilege of our children to attend schools where they learn the truth about the world in which they live. We also recognize the forces which have been trying to falsify American history — the forces which drive many Americans to a corner of compromise with those who would distort the ideals of men that died for freedom.

Sometimes we walk across the land looking for something to hold on to. We cannot believe that the resources of this country are exhausted. Even when we see our children suffer humiliations, we cannot believe that America has no more place for us. We realize that what is wrong is not in our system of government, but in the ideals which were blasted away by a materialistic age. We know that we can truly find and identify ourselves with a living tradition if we walk proudly in familiar streets. It is a great honor to walk on the American earth.

If you want to know what we are, look at the men reading books, searching in the dark pages of history for the lost word, the key to the mystery of living peace. We are factory hands, field hands, mill hands, searching, building, and molding structures. We are doctors, scientists, chemists, discovering and eliminating disease, hunger, and antagonism. We are soldiers, Navy men, citizens, guarding the imperishable dream of our fathers to live in freedom. We are the living dream of dead men. We are the living spirit of free men.

Everywhere we are on the march, passing through darkness into a sphere of economic peace. When we have the freedom to think and discuss things without fear, when peace and security are assured, when the futures of our children are ensured — then we have resurrected and cultivated the early beginnings of democracy. And America lives and becomes a growing part of our aspirations again.

We have been marching for the last 150 years. We sacrifice our individual liberties, and sometimes we fail and suffer. Sometimes we divide into separate groups and our methods conflict, though we all aim at one common goal. The significant thing is that we march on without turning back. What we want is peace, not violence. We know that we thrive and prosper only in peace.

We are bleeding where clubs are smashing heads, where bayonets are gleaming. We are fighting where the bullet is crashing upon armorless citizens, where the tear gas is choking unprotected children. Under the lynch trees, amidst hysterical mobs. Where the prisoner is beaten to confess a crime he did not commit. Where the honest man is hanged because he told the truth.

We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.

If you want to know what we are — we are marching!

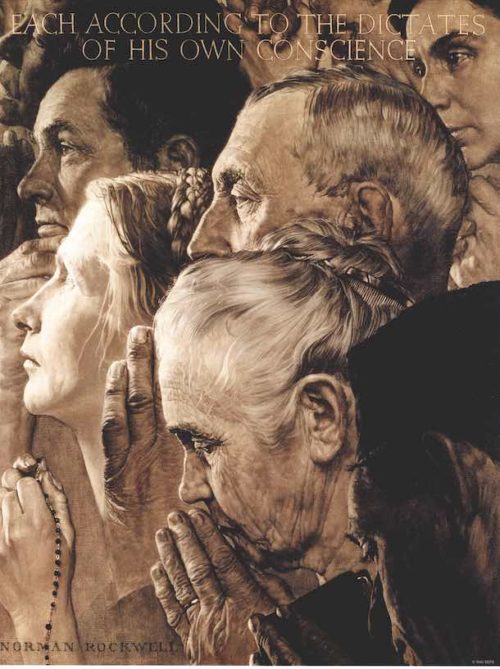

Will Durant’s ‘Freedom of Worship’

In 1943, the Post commissioned four writers to craft an essay to accompany each of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, which had quickly come to represent America’s moral imperative during World War II. You can read the other three essays here.

Freedom of Worship

Originally published February 27, 1943

Down in the valley below the hill where I spend my summers is a little white church whose steeple has been my guiding goal in many a pleasant walk.

Often, as I passed the door on weekdays when all was silent there, I wished that I might enter, sit quietly in one of the empty pews, and feel more deeply the wonder and the longing that had built such chapels — temples and mosques and great cathedrals — everywhere on the earth.

Man differs from the animal in two things: He laughs, and he prays. Perhaps the animal laughs when he plays, and prays when he begs or mourns; we shall never know any soul but our own, and never that. But the mark of man is that he beats his head against the riddle of life, knows his infinite weakness of body and mind, lifts up his heart to a hidden presence and power, and finds in his faith a beacon of heartening hope, a pillar of strength for his fragile decency.

These men of the fields, coming from afar in the uncomfortable finery of a Sabbath morn, greeting one another with bluff cordiality, entering to worship their God in their own fashion — I think, sometimes, that they know more than I shall ever find in all my books. They have no words to tell me what they know, but that is because religion, like music, lives in a world beyond words, or thoughts, or things. They have felt the mystery of consciousness within themselves, and will not say that they are machines. They have seen the growth of the soil and the child, they have stood in awe amid the swelling fields, in the humming and teeming woods, and they have sensed in every cell and atom the same creative power that wells up in their own striving and fulfillment. Their unmoved faces conceal a silent thankfulness for the rich increase of summer, the mortal loveliness of autumn and the gay resurrection of the spring. They have watched patiently the movement of the stars, and found in them a majestic order so harmoniously regular that our ears would hear its music were it not eternal. Their tired eyes have known the ineffable splendor of earth and sky, even in tempest, terror, and destruction; and they have never doubted that in this beauty some sense and meaning dwell. They have seen death, and reached beyond it with their hope.

And so they worship. The poetry of their ritual redeems the prose of their daily toil; the prayers they pray are secret summonses to their better selves; the songs they sing are shouts of joy in their refreshened strength. The commandments they receive, through which they can live with one another in order and peace, come to them as the imperatives of an inescapable deity, not as the edicts of questionable men. Through these commands they are made part of a divine drama, and their harassed lives take on a scope and dignity that cannot be canceled out by death.

This little church is the first and final symbol of America. For men came across the sea not merely to find new soil for their plows but to win freedom for their souls, to think and speak and worship as they would. This is the freedom men value most of all; for this they have borne countless persecutions and fought more bravely than for food or gold. These men coming out of their chapel — what is the finest thing about them, next to their undiscourageable life? It is that they do not demand that others should worship as they do, or even that others should worship at all. In that waving valley are some who have not come to this service. It is not held against them; mutely these worshipers understand that faith takes many forms, and that men name with diverse words the hope that in their hearts is one.

It is astonishing and inspiring that after all the bloodshed of history, this land should house in fellowship a hundred religions and a hundred doubts. This is with us an already ancient heritage; and because we knew such freedom of worship from our birth, we took it for granted and expected it of all mature men. Until yesterday, the whole civilized world seemed secure in that liberty.

But now suddenly, through some paranoiac mania of racial superiority, or some obscene sadism of political strategy, persecution is renewed, and men are commanded to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto Caesar the things that are God’s. The Japanese, who once made all things beautiful, begin to exclude from their realm every faith but the childish belief in the divinity of their emperor. The Italians, who twice littered their peninsula with genius, are compelled to oppress a handful of hunted men. The French, once honored in every land for civilization and courtesy, hand over desolate refugees to the coldest murderers that history has ever known. The Germans, who once made the world their debtors in science, scholarship, philosophy, and music, are prodded into one of the bitterest persecutions in all the annals of savagery by men who seem to delight in human misery, who openly pledge themselves to destroy Christianity, who seem resolved to leave their people no religion but war, and no God but the state.

It is incredible that such reactionary madness can express the mind and heart of an adult nation. A man’s dealings with his God should be a sacred thing, inviolable by any potentate. No ruler has yet existed who was wise enough to instruct a saint; and a good man who is not great is a hundred times more precious than a great man who is not good. Therefore, when we denounce the imprisonment of the heroic Niemoller, the silencing of the brave Faulhaber, we are defending the freedom of the German people as well as of the human spirit everywhere. When we yield our sons to war, it is in the trust that their sacrifice will bring to us and our allies no inch of alien soil, no selfish monopoly of the world’s resources or trade, but only the privilege of winning for all peoples the most precious gifts in the orbit of life — freedom of body and soul, of movement and enterprise, of thought and utterance, of faith and worship, of hope and charity, of a humane fellowship with all men.

If our sons and brothers accomplish this, if by their toil and suffering they can carry to all mankind the boon and stimulus of an ordered liberty, it will be an achievement beside which all the triumphs of Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon will be a little thing. To that purpose they are offering their youth and their blood. To that purpose and to them we others, regretting that we cannot stand beside them, dedicate the remainder of our lives.

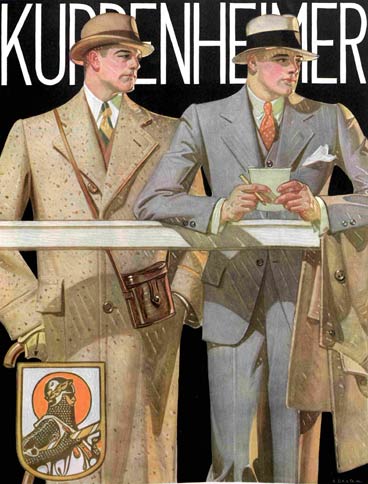

Why Do Men Dress That Way? 1930s version.

In case you hadn’t noticed, fashionable clothing for men has barely changed over the past 200 years.

The coat-tie-trousers-hat ensemble was established in the 1820s. The only significant change has been the abandonment of the hat, once the most personal and most expressive item in a man’s wardrobe.

While the basic elements have remained constant, men’s clothing has seen countless variations over the past two centuries. Each year, it seems, brings new coat lengths, tie widths, and lapel cuts. But as this 1930 advertisement shows, there is a strong resemblance between the suit of today and of 70 years ago.

In the ’30s, a Post article posed the question that has occurred to most men who’ve wandered the aisles of a clothing store and shaken their head at the strange, new fashions: “Where do they come up with this stuff?” Based on his experience as a buyer, Arthur van Vlissingen declared that new styles weren’t dictated by either clothing retailers or manufacturers; neither could afford to gamble on an upcoming trend.

New styles become popular only when men see other men wearing them. “Men, unlike women, seldom discard a garment simply because the style has meanwhile changed. The average man who buys one of our suits wears it until, from his standpoint, it is worn out. … But men are none the less sensitive to style. They will [only] buy clothing which is … the fashion in their social circles, whatever these circles may be. They are determined to start even with their fellows every time they get new outfits,” Vlissingen wrote.

But this only explains how styles grew, not how they were born. He explains that, ultimately, new fashions were started by men who had their clothes made for them. These men included the successful executive, who needed to prove his ability to sense a new trend and his willingness to invest in it. Also included was the salesman, who had to demonstrate to his customers that he was aware of the latest developments, both in his own business and in fashion.

Younger men followed “styles which take shape at the places where the country’s leisured and socially prominent loaf, such places as Palm Beach and Newport, Aiken and Southampton, White Sulphur and Virginia Hot Springs.”

Another major influence on fashion in the 1930s was college—one university, in particular. “The fashions in clothing worn by our male population, between the ages of 14 and perhaps 25, usually get their start at Princeton,” Vlissingen wrote.

“Harvard is a very large university, in a great city which influences the students’ styles heavily. [But] it holds to a tradition of careless dress—well-made clothes seldom dry-cleaned and never pressed. Yale is more compact and more finicky, but New Haven is also a large city. Princeton is in a smaller town, off by itself where it can incubate a style effectively. Practically every Princeton student is well dressed, whereas only one-third or so of the Yale men can qualify by our standards.”

Whether they were at a resort or on a campus, these young men made up “a selective group of people, to whom adheres social prestige, [which] absents itself from cities all over the country. During their absence these men quite unconsciously decide what sorts of clothing they wish to wear. Then they scatter to their homes and are imitated by their friends, from whom, in turn, the style spreads in ever-widening circles.”

In addition to the fashion example set by the successful executive or the big man on campus, American men’s tastes were strongly influenced by the clothing they saw actors wearing in motion pictures.

Mr. Jinks, the well-known wholesale grocer of a mid-Kansas town, would indignantly and honestly deny that he buys his clothes according to what he sees at the movies. But the chances are that his clothier can recognize in Mr. Jinks’ halting description of the suit he wants, the outfit against which Marlene Dietrich pillowed her comely cheek at the Lyric last night.

No longer can a New York salesman come into Mr. Jinks’ store wearing a shepherd-plaid suit with two-inch checks, a red necktie, with a diamond horseshoe, and a pair of high-yellow shoes—not if he wants Mr. Jinks to think he’s dressed in the latest style.

Mr. Jinks may not be particularly alert about styles, and maybe he has not been in a town of more than 25,000 population for two years. But, like almost everyone else on the North American continent, Mr. Jinks goes to the movies. So does the traveling salesman. Which helps to account for the fact that the old-fashioned traveling man in loud clothes has gone the way of the passenger pigeon. Douglas Fairbanks and his well-dressed fellows have done him to death.

Gone are the days when movies introduced men to elegant dinner jackets, stylish sport coats, and raffish neckwear. Today’s movies are more likely to reflect the style du jour: work pants, T-shirt, and baseball cap, which are worn by movie moguls, software tycoons, and every big man on campus. Perhaps the 200-year-old fashion for men will, at last, be replaced.

1930s Fashion: Men’s Suits

Helping Men Become Better Caregivers

For many families, caregiving duties automatically fall to women. According to an AARP study, most caregivers are female. But the same study showed that more men are starting to take on the caregiver’s role. That’s good news on the gender equality front. But if things are getting fairer, there’s still progress to be made. And to put it plainly, male caregivers could use a little help.

Marc Silver discovered this firsthand when his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2001, and though he stood by her and eventually figured out how to be a good caregiver, he’s the first to admit he made plenty of mistakes along the way. After their ordeal (his wife is doing fine at present), he wrote an instruction manual to help other caregiving-challenged men. His book is called Breast Cancer Husband, How to Help Your Wife (And Yourself) Through Diagnosis, Treatment, and Beyond. I recently caught up with Marc to talk about his experiences and to find out what advice he has for other men.

Q: Why do men need extra help when it comes to caregiving?

A: Caregiving is a role that a lot of guys are unfamiliar with, and particularly in the case of breast cancer, it is thrust upon them with no time for preparation. Personally I just remember feeling totally clueless and getting a few things completely wrong.

Q: For example?

A: Well, my wife Marsha called me immediately after her diagnosis. She’d just been told out of the blue that she had breast cancer. She was looking for some husbandly advice and solace, and my first reaction over the phone was, “Ew, that doesn’t sound good.”

Q: Uh, oh.

A: It gets worse [laughs.] We continued to talk a bit more, but only about logistics, when what she was needing at that point was sympathy and compassion. Then, at the end of the conversation I hung up, stayed at work all day, and didn’t come home until the usual hour.

Q: What did your wife say about that?

A: Marsha told me later, “I must have called the wrong husband.”

Q: In doing research for your book, did you find that your initial reaction—let’s be nice and describe it as missing her emotional cues—was a common one?

A: There are plenty of examples of men who ran straight home to be there for their wives when a cancer diagnosis was made. But yes, many men make mistakes like these, and I’ve heard of worse.

Q: Like what?

A: After a speaking engagement for my book, a couple came up to me and the husband told me that his reaction to his wife’s diagnosis was, “Well, you want to stop for dinner at Hooters?” I asked him if he was trying to be ironic or funny, but he insisted he was just thinking about a good place to get a meal.

Q: Sounds like men can’t cope initially and go into autopilot. Is this denial?

A: Yes, I think so. But it’s a very human reaction. One therapist I interviewed for the book said, “Nobody is sitting there saying, ‘Oh gosh, I hope I get to be a caregiver for a loved one who is diagnosed with cancer.’”

Q: So, guys shouldn’t beat themselves up too much about initial blundering?

A: No, they shouldn’t. That is very important. It is inevitable that you are going to do things that are going to tick your wife off or be not the kind of things she needs at that time. But you can learn from that. A lot of woman said to me that the motto for the husband is: “Shut up and listen.”

Q: Is there something inherently different about men that makes it harder for them to be good caregivers? Or, are men just not socialized to get it? Is it nature or nurture?

A: In my research I found a little bit of both. Men are simply not taught to tune in to others emotionally the way women are. On the nature side, doctors point to studies showing women have more of the hormone oxytocin, which promotes empathy.

Q: Still, it sounds like you’re saying, with some help, men can and do learn to be better caregivers.

A: Yes, absolutely. A big challenge is that men like to be problem-solvers. Instead, they need to learn that their role, as a caregiver, is to be an echo or a foil: Let her talk things through with you without interrupting to say, “here’s what you should do.” You’re not supposed to be in charge here. She is the boss.

Q: Does that make you the assistant?

A: Yes, exactly.

Q: Can you give an example of being supportive, without taking charge?

A: It is very common for a patient to be overwhelmed by all of the medical information. So, it’s important to join her at all medical appointments. Make lists of her questions for the doctors prior to each visit, and keep the list in front of you during the visit to make sure all of them get answered. Also, take good notes on these medical conversations so you can go over the details later.

Q: Your book title stresses helping your wife and yourself. How so? Isn’t that selfish?

A: Part of what you have to do as the caregiver is to be selfish sometimes. Whether it’s going out for a bike ride or watching a movie you like. You need time for yourself to recharge.

Q: So, if caregivers have a need to, say, go play golf or take a bike ride for a few hours, that’s ok?

A: Yes, but I would always ask my wife’s permission first. I interviewed Cokie Roberts for the book. She said when she was going through breast cancer, friends would call up and ask what could they do. And her first response was: “Play tennis with my husband.” It is certainly much harder to be the patient, but it is tough to be a caregiver too.

Steven Slon is the editorial director for The Saturday Evening Post. This column was first published by Beclose.com.