North Country Girl: Chapter 33 — The End of Childhood

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. This is the last chapter in the series.

Michael Vlasdic’s mother, the German professor, was always obliging; that summer, she taught a full load of classes, leaving Michael’s house delightfully parent-free for hours and hours. I loved Michael. I never wanted to leave his arms. To be with him, I had spent the past six months fretting over my personal monthly calendar — is it safe to have sex this day? The day after? After every “safe” day I was convinced I was pregnant and doomed right up until my trusty body proved otherwise.

Now the 60s made a further encroachment in Duluth: Planned Parenthood came to town. Until then, the only doctor I knew was my pediatrician, Dr. Bergman, who had seen me in my white Carters undies and examined me for pinworm.

The girl grapevine went into full swing. “I heard if you’re sixteen you can get birth control at Planned Parenthood and they don’t tell your parents,” said a wide-eyed Wendi Carlson. I was one of their first customers. I was so desperate to have as much sex as possible with Michael, to be free of the tyranny of the menstrual cycle, that I turned up at their downtown office and bravely asked to see a doctor. I was ushered into the exam room of a very nice woman doctor, another thing I had only seen on TV. I cringed through my first pelvic exam, even though the nice doctor complimented me on my “textbook cervix.” When my legs were back together and on the ground, the doctor handed me a prescription that read “To regulate flow” and told me to come back in a year.

I had drugs and Michael and his empty house and no more worries about being knocked up. It was a fun summer. I tried to be mindful of the time on my work day when I had to punch in at The Bellows at four to make sure that those idiots who showed up for a steak dinner at five would have a fresh crisp salad. But we were insatiable. One afternoon, as I felt Michael poking me in the leg, ready for a third bout, I raised my kiss-swollen face up off the bed and saw to my horror that it was a quarter to four. Michael was pulling me down; of course he didn’t understand why I had to be at The Bellows on time. Unlike everyone else I knew, Michael did not have a summer job. He refused on principle to work for the man. “Who cares if you’re a few minutes late?” he grumbled. “It’s not like you’re doing anything important.”

The real German, I was determined to keep the salads running on time. I threw on my clothes, not bothering to wash. Michael grudgingly offered to walk me the ten minutes down to The Bellows. Walk? I need to go at a quick trot to get there on time.

I was two blocks away from the restaurant, waiting at the corner to cross the busy-for-Duluth Superior Street. Traffic finally slowed as a bus pulled up and stopped. I started to dash across the street, certain Michael was beside me. But he had seen the car behind the bus veer left to go around it. I did not. I felt a bang and landed on the hood of a cab, looking into the horrified face of the driver. The next thing I knew I was on the ground and Michael was standing over me, red-faced and sobbing, as the bus driver and the cab driver both shot out of their vehicles. I assured everyone I was fine, and got up to continue on to work. No one was going to let that happen; I was guided over to the curb by several hands and forced to sit. Soon an ambulance showed up, and even though I was still protesting — who would make the salads and defrost the shrimp? — I was loaded inside. Before they shut me in, I called over Michael, who bent over me for my last words, which were to call The Bellows and explain that I had been hit by a car.

At St. Luke’s Hospital I was X-rayed and palpitated and asked if I knew the name of the president and what day of the week it was. I did, and nothing was broken; when my father showed up (who had called him?) they were ready to release me. I pulled my jeans on over the yellow and purple bruise that covered my left leg from knee to hip, pushed myself off the examination table and fell over. I could not put any weight on that leg.

My father drove me home in silence, then helped me onto the living room couch, the first time he been in the house since the day he left. He stayed until my mother finally bustled in, furious at having been summoned home by some stupid kid thing, and even angrier that my dad got to act the part of the responsible parent. As soon as he was gone, she lit in to me: how in the world does anyone get hit by a car? Couldn’t I see it coming? She was also suspicious of where I had been all that afternoon; it was July, I was not doing homework at Michael’s house.

In a few days I had recovered enough to lean against the big stainless steel sink at The Bellows, peeling shrimp and cracking oysters; and to figure out ways to make love on Michael’s narrow bed without his weight, however slight, on my injured thigh. Michael kissed the bruises, fading into less corpse-like shades, and told me how sorry he was, how he had just been about to warn me when I went teacups over kettles on the hood of the taxi. He did not feel badly enough to go out and look for a job himself; I kept working and kept spending my paycheck on drugs.

Summer ended and that golden age of youth, senior year, started. Saturdays were still reserved for Michael and acid, but every Friday I was with my friends in the White Delight, cruising up and down Duluth, in search of where the action was. Our senior year parties became wilder, more abandoned, with more booze, more drugs, and dozens of kids in various stages of intoxication. We huddled around house-sized bonfires on the lake shore, tossing empties into the flames and laughing hysterically at nothing. We smashed into the Anderson’s basement; the crescendo of “Stairway to Heaven,” still new to our ears, made conversation impossible and unnecessary.

There were a few casualties. Betsy James had a fight with her boyfriend, and took off on his motorcycle; he found her a block away pinned under it, with a broken leg and a large patch of her skin left on the asphalt. Craig Whiteman, one of East’s few greasers, polished off a six-pack of Grain Belt at a party and accepted a dare to break into old lady Congdon’s mansion. No one knew that Dorothy Congdon was a champion skeet shooter who slept with a loaded shotgun beside her.

My band of sisters grew closer together as high school graduation neared. We had forged a sacred bond, at a time when our hearts and souls were soft and malleable, and our feelings strong and blood hot. Our friendship was built on years sharing our teenage loves and disappointments, laughing, drinking, sometimes crying, and always caring deeply. We knew that college and jobs, new lovers and new friends, would soon disrupt the centrifugal force that kept us together, though we vowed not to let that happen.

Michael and I also believed with the fervor of a religion that we were destined to be forever together, the fever dream of first love. But while I had despaired every time my period was half a day late, Michael romanticized the possibility of us having a baby. He longed for an addition to his tiny two-person family and got all misty-eyed listening to Crosby, Stills, and Young’s “Our House.” We shared a dream of a small apartment in Minneapolis, filled with sex and drugs, college textbooks and cats, where we would fall asleep in each others’ arms, but my dream definitely did not include a baby.

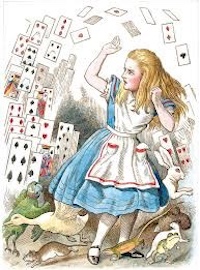

While my heart was sworn to Michael, the rest of me was stirring with other desires. Being safely on the Pill turned a key in my mind, which opened up a new world of sexual possibilities. Emily Dickinson wrote “There is no frigate like a book, To take us miles away,” and for years books had been my only escape from my stolid small town life and boring middle-class family. I could get lost again and again in the exploits of Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf, Arthur and Merlin, Dorothy and Alice, and all those other plucky young heroines. Then I discovered that drugs could shanghai my mind, transport me to different realms. Now I realized that there was another vehicle that could take me away on adventures: my own body.

I started looking at other boys with a hungry curiosity. What would it be like having sex with them? How would they smell, how would they touch me? Would the sex be better or just different? And maybe just different would be exciting enough. According to Time magazine, which still made its weekly appearance in our mailbox, the sexual revolution was in full swing. I was a willing recruit to any revolt. Even my own mother, still pretty at thirty-seven and post-divorce slim, had seduced a former stalwart of the Catholic Church and father of six, and was busy trying to get him to dump his wife and marry her.

The culture, my body and mind, and the nice people at Planned Parenthood were all encouraging me to expand my sexual horizons; the only reason not to was that Michael, my sensitive, moody lover, would be hurt. So I never told him about the others. I was callow and callous, and from a distance of many years, I can see that I was not the adventuress I thought I was — just an asshole.

There was Jonathan, who had been making me laugh since seventh grade advanced math. He was a behind-the-scenes stagehand for all our aspirational high school plays, painting flats, adjusting the lights, and cracking up everyone in earshot. The plays our high school put on were ancient chestnuts, chosen for their ability not to offend anyone: starting with “My Three Angels” (misspelled on every poster as “My Three Angles”), about a trio of fugitives from Devil’s Island, through “You Can’t Take It With You,” with its cast of thousands.

That play provided my one chance for glory on the stage. I had been trying out in vain for a part in one of East’s plays since I was a sophomore. Our creepy drama teacher Mr. Canfeld had given every single leading role for the past three years to milquetoast Grace Myers; rumor had it that she let him feel her up. On my ninth audition for him, Mr. Canfeld felt sorry for me, ignored my lack of acting ability, and cast me as Olga, the White Russian countess, who shows up in the final act to deliver her three lines. After our second and closing performance, cast and crew gathered in somebody’s parent-less house for one of the epic theater parties. Drunk and high, Jonathan and I were talking, then giggling like lunatics, then kissing. We locked ourselves in a bathroom so we could take some of our clothes off. As I had hoped, it was different and it was fun, like taking a roller coaster ride together. Miraculously, Jonathan and I became better friends.

One sub-zero Saturday night, Michael Vlasdic and Needle both sick with the flu, Roger and I ended up alone, driving aimlessly around Duluth in search of a party. Sitting next to him on the front seat, like boyfriend and girlfriend, I realized I liked his craggy profile and scooted over a little closer, feeling a pleasurable tingling. When Roger put his arm around me, a bolt shot through my body to where his hand rested on my shoulder; we both felt the electricity through our winter woolens. Without saying a word, Roger steered for Skyline Drive, the favorite parking place for Duluth teens. We stretched out as much as we could in the back seat and committed our double betrayal, he of his friend, me of my soulmate. When we were done, we felt a bit bad and swore it could never happen again. But it did, and it was furtive and secret and thrilling.

I had always had a little crush on handsome, sleepy-eyed Jack France, who showed up occasionally at Open Mind meetings to read his angsty poetry. He was like me, a flitter among groups, a smart athlete who got high. Now I side-eyed him in Mr. Burrows’ class, where he sat alone in the back, gazing out the window. I wondered what it would be like to kiss him.

I found out on a yellow Bluebird bus making its bumpy way back from Telemark, Wisconsin, after a day of spring skiing. Nancy Erman had organized a school ski trip, one of the last hurrahs of our senior year. We skied stripped down to sweaters and blue jeans, luxuriating in the sunshine that was almost warm. There was such joy in the day, in our forever young bodies that we sent hurling recklessly down the slopes, again and again, until the lifts slowed and stopped and it was time to go home. Jack and I had skied together that day, and it didn’t take much wrangling on my part to end up sitting next to him on the tot-sized school bus seat. Jack shook out a package of Lucky Strikes from his pocket and lit a cigarette. Then we kissed. I thought I was the world’s best, most experienced seventeen-year-old kisser; I was knocked for a loop. Jack’s kisses shrunk the entire world down to the two of us, nothing but slightly chapped lips and gentle exploring tongues and the taste and smell of tobacco which reminded me of fall’s burning leaves. On the bus, in parkas and long johns and snow-soaked Levi’s, there was nothing more we could do than kiss, and the kisses were everything.

Jack and I never went any further. For years, every time we ran into each other, Jack and I would end up in dark corners where we shared those deep soulful kisses, sometimes for hours, until he took off one autumn on a solo cross-country bike trip to Seattle, where he leapt off the George Washington Memorial Bridge.

Being with Jonathan, Roger, and Jack was fun, it was sex with no agenda, no strings attached. It wasn’t about love, or negotiating a relationship, or even about my desperate desire to be thought of as pretty and sexy and cool.

I was beginning to regret the plans that Michael and I had made, that we’d go off together to the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and live happily ever after. I was going to spend my first year in a dorm; he would stay with a friend of his mother’s who had offered him almost free rent and board. Eventually we would find an apartment and move in together. In the pleasant mist of these daydreams, I didn’t think about how we would pay the rent; his mother had no money, I knew neither of my parents would subsidize my living in sin, and Michael had never shown the slightest desire to find a job. I had left the salad and the shrimp at The Bellows behind; my vast restaurant experience got me hired as a waitress at The Flamette, where despite my dropping a full glass pitcher of maple syrup my first day and my inability to carry more than two plates at a time, I was making enough to buy drugs and squirrel away some spending money for college.

East High had no guidance counselors to talk to about universities; the only adult who had spoken to me about college was my grandmother, who offered to pay my tuition if I went to St. Scholastica, a Catholic woman’s school right there in Duluth. No thank you.

I filled out the application for the University of Minnesota, wrote the essay, tore out and filled in a check for $15 from my mother’s checkbook (she had finally gotten her own bank account), and sent the package off to Minneapolis, never doubting that I would get in and never considering applying to any other schools. The housing catalog that came with my acceptance letter featured a brand new, co-ed dorm, the only dorm that allowed 24-hour visitation from the opposite sex — as long as you had your parents’ permission. I checked the box for Middlebrook Hall on my housing form, forged my mom’s name on the permission slip, and fell into a fantasy of unlimited sex with unlimited college boys, with an occasional guest appearance by Michael Vlasdic.

For once the reality matched the daydream. My perky, adorable, All-American college roommate, Nancy Lowe, went back to her suburban home every weekend to work at the local pizza place and have sex with her own boyfriend, leaving me a wonderfully empty dorm room for entertaining. I was sandwiched between boys; at Middlebrook Hall the sexes alternated floors. My new friend Liz Hepper, who I had met in her dorm room closet, where she was chugging a bottle of Southern Comfort, introduced me to a herd of funny, smart boys from her hometown of Rochester, including a pharmacy major who had very good drugs. There were so many boys in my dorm, and they were all so interesting and cute. And out on the huge campus there were 20,000 more, surrounding me in class, eating dinner in the cafeteria, napping or reading or throwing Frisbees on the still-green campus lawns.

Despite all our plans, despite my absent roommate and the 24-hour visitation, despite how much I thought I looked forward to the first time I could sleep with him, entwined and spooned and inhaling his sweet spicy scent, Michael and I never spent a single night in my skinny dorm bed.

Before the first week of college was out, I called Michael and broke up with him, in the worst way possible, over the phone.

There was another important phone call that first month of my freshman year. My mother called to tell me that she was moving to Colorado Springs. She did not tell me that she was moving in pursuit of the ex-Catholic father of six, who had finally left his wife; he had also left Duluth to live on a small ranch in Colorado. I was instructed to come back home that weekend to box up anything I did not want sold or thrown out; my mother and sisters were downsizing from a six-bedroom stately home to a two-bedroom apartment.

I wandered through 101 Hawthorne, most of the rooms already empty of furniture. Almost everything was gone from my old bedroom, where I had spent so many nights tripping, transfixed by the golden glow from the streetlight streaming through the trees. A few summer clothes hung in my closet; I put them in my suitcase, looking forward to catching some boy’s eye in my cute Indian-print sundress in the spring.

I went back down to the TV room, where our bookshelves were, and where two large cardboard boxes sat gaping. “Put what you want to keep in one,” said my mother. I pulled from the shelves the books that had been my youthful frigates: Alice’s Adventures, the Tennile drawings only slightly defaced from Crayolas wielded by my sister Lani. The Wizard of Oz. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. The Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Anderson, minus “The Little Mermaid” and “The Little Match Girl.” I opened up the books Michael had given me, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, each frontispiece signed “I love you” illustrated by his round smiling face. My heart gave a small twist as I stowed them in the moving box. Next came the never-paid-for plays of William Shakespeare, three heavy tomes, The Histories barely cracked. I added The Guide to Minnesota Fauna and Flora, which had been handed to me by the outdoorsy old lesbian who had dragged me around Duluth’s fields and woods. Here was Angelique and the Sultan, with steamy seduction scenes on every page, never returned to Kathy O’Dell. A ragged paperback sci-fi novel, The Blind Spot, that I had read three times in a row, on that trip to Mexico, lacking any other English-language reading material that was not dental-related. And of course the fruit of my junior year with Mr. Burrows, the two volumes of American history and literature, typed out night after night, with my name printed on the spine in gilt letters.

I sealed my cherished books up in a moving box and told my mother that was all I wanted shipped to Colorado. That Christmas break, in my mom’s ticky-tacky Colorado Springs apartment, I sat in the living room, hemmed in by our old furniture: the mahogany dining table for six, the gold and cream French Provincial sofa and matching end tables, and the immense cabinet TV. I opened a cardboard box identified as “Gay’s Books” in black marker. It contained stained Junior League cookbooks, several years of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, a collection of Harold Robbins paperbacks, a single addendum to the World Book, dated 1960, and a battered Webster’s dictionary. My childhood was gone.

North Country Girl: Chapter 32 — Bamboozled at East High

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

As if we were still in elementary school, we teenagers delighted in anything that was a disruption in the school day. One poor kid, not the brightest light in the harbor, made a series of phone calls to the East office, claiming he had placed a bomb in the school, freeing the rest of us outdoors into the grey chill of a Duluth spring, no time to fetch coats or mittens from our lockers. Standing where somebody decided was a safe enough distance from a bomb, we kept warm by huddling in our little cliques, reveling over being sprung from chemistry or French II or metal shop.

Since the fake-bomb-threat miscreant had been spotted at the school’s one and only pay phone immediately before each evacuation, we all knew who he was, but our lips were sealed. The last time he called in a bomb threat, he must have been unhinged by the many thumbs up shot his way by passing students; he stuttered out to the school secretary, “And this isn’t (miscreant’s name)!” We never saw him after that.

Assemblies also broke up the school day; unlike the thunderous pep rallies held in the acoustically challenged gym, during assemblies you could have a whispered gossip or flirtation with the person next to you or even go to sleep.

One morning the crackly voice of Mr. Srdar, the principal, came over the ancient mesh loudspeakers mounted in every classroom. “Attention students: There will be a special assembly at ten o’clock tomorrow. All students are required to attend.” Rumors flew: was a friendly policeman in uniform coming to talk to us about drugs? Did they finally figure out which teacher was sleeping with his students? The worst scenario was yet another visit from Junior Achievement, touting the virtues of capitalism and on the prowl for future Titans of Industry. If that were the case, at least we could all catch an hour nap.

The next day we trooped into East’s auditorium and reverted to rowdy eight-year-olds; the big room rang with shouts, laughter, and whistles. The principal shushed us down into a quiet roar, and we jostled for seats, seats whose wooden bottoms had been worn so slick and shiny by generations of teenage bottoms that if you slumped or fell asleep you were in danger of sliding to the floor.

Mr. Srdar stood at the podium someone had thoughtfully placed on the left side, where it caught the watery spring light. He introduced the day’s special guest, who would speak to us about the famine in Africa.

This was unexpected and shut us up. We looked from side to side, acknowledging that every single one of us, even kids who couldn’t find the world’s second largest continent on a globe, had been implored to “Think of the starving children in Africa” when staring down a plate of grey meatloaf, calf’s’ liver, or boiled-to-death broccoli, which was supposed to make the disgusting mess more appetizing.

An earnest young man in khakis stepped up to the podium, introduced himself, and spoke about the war in Biafra, waving around a copy of National Geographic. He described the starving children he had seen, their stomachs bloated, their eyes dull. He said when the children’s hair turned red it was a sign that they were dying. Their bodies were not taking in enough nutrients to create the dark hair pigment: a little red-haired African child was a walking corpse.

He was good, so good that no one questioned why he had no photos, only a copy of a magazine, or why, if he was just back from Africa, he was as pale as any Minnesotan in March.

When he made a little choking noise in his throat, and dropped his head, girls all around me started to weep, searching in their bags for Kleenex to blot their tears and blow their noses. Even a few of the boys were squirming and blinking. This went on for a while, the young man droning on with his dramatic descriptions of dying kids and keening mothers. I wondered what the hell is going on here?

Then came the pitch. This nice young man was raising money for the starving children of Africa (no, we still couldn’t just send them our spinach and fish sticks) through a brand new kind of fund-raiser: a Walk-A-Thon, a 20-mile trek through Duluth. To participate, we had to ask our parents, parents’ friends, aunts, uncles, grandparents, any available adult with money in pocket, to sponsor us at so much a mile — preferably a dollar.

He said, “Imagine you’re holding a little African in your arms. Imagine that baby’s scrawny limbs, the distended belly barely covered in rags, the head that seems too large topped with a scruff of tightly curled, rust-colored hair. That baby is looking at you with big brown eyes, pleading for help. If you do not participate in the Save Africa Walk-a-Thon, you are dumping this poor dying baby out of your lap and letting that baby die.“

Even the football players were sniffing now, and some girls were red-faced from bawling. Mr. Srdar dabbed his own wet eyes with a big white hankie, congratulated the young man on the noble work he was doing, and assured him that he could count on East High students.

The Walk-A-Thon was scheduled for that Saturday. We were told the meeting place and instructed to bring our sponsors’ money with us. We were not given sign-up sheets, collection envelopes, buttons, pamphlets, or t-shirts. None of us thought this was odd as we went about pestering parents, family friends, and relatives for money.

I knew better than to ask my own mom, certain what her response would be to giving away money to perfect strangers. My dad and one set of grandparents were Missing In Action, the other grandparents hundreds of miles away. I walked over to Lakeview Avenue, my old block, and knocked on the McCauleys’ door; they were an older couple who were always good for a couple of boxes of Thin Mints or Samoa Girl Scout cookies. I was not nearly as eloquent as the young man and had a hard time explaining why Mrs. McCauley should give me the immense sum of twenty dollars so I could go on a walk. She pulled a crumpled one from a change purse, I took it, thanked her, and headed over to Michael Vlasdic’s house.

Michael was not walking. He had no interest in any extracurricular activities besides listening to records, taking drugs, and screwing me. Always a good sport, Mrs. Vlasdic gave me a twenty and told me I was a gutes Maedchen.

On a bright spring morning, a sympathetic mother delivered me and a passel of my friends to the Walk-a-Thon starting point, where the young man stood with a clipboard, writing down kids’ names, taking their money, handing out blurry mimeographed maps, and thanking us for saving all those babies’ lives.

We were somewhere in West Duluth, a neighborhood I hadn’t been in for years, and then only to visit the small and smelly Duluth Zoo, where an irate, aggressive and way too close squirrel monkey had once tried to snatch my mom’s beehive hairdo off her head. As I squinted at the blurry map, trying to make sense out of all the random rights and lefts, the young man blew a whistle and we headed off en masse.

The first five miles weren’t so bad, we were with our friends, we were outside in the fresh sun of spring, joking and laughing, and extremely proud of ourselves. We were the better angels, the generation that was going to save the world. The next month, on April 22, a bunch of us do-gooders would be down on Park Point beach, celebrating the first Earth Day, saving the planet by creating rickety sculptures of driftwood while tripping on LSD.

By mile 10, there was no more laughter, only silent plodding. We wore flimsy sneakers and carried nothing; running shoes, bottled water, and energy bars had yet to be invented. I don’t know if anyone made it past the fifteen-mile mark. At that point I hobbled home, fell on the couch, and gingerly took off my Keds and ankle socks to reveal swollen, throbbing, blister-covered feet, while my mom yelled at me for being gone all day without calling.

What hurt even worse was finding out that our nice young man was not saving babies, but lining his own pockets. Too late Mr. Srdar got a phone call from a high school in St. Cloud, telling him to be on the lookout for a traveling flimflam man, who like Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man, went from one innocent small town to the next, selling us nothing, not even big trombones or ratatat drums.

Even though I had watched Michael Vlasdic tear up during that hornswoggle of a speech, now he was miffed that I had given away his mom’s twenty dollars, which would have bought four hits of acid.

Since my father had left, my own cash flow had trickled down to nothing. My mom did not have a bank account in her name. It took several phone calls and several weeks before my dad would reluctantly show up to place some actual cash in my mom’s hand. She would then, almost as reluctantly, peel off a few bills for me. From that pittance I had to pay for my share of gas and booze on Friday nights with my pals, and for the drugs Michael and I took on Saturday.

But suddenly it was summer, school was out, and I was sixteen, old enough to find a job. The Flamette, a diner that was swarmed with tourists in the summer, hired high school girls. My friends Nancy, Betsy, and Debbie waitressed there, I looked on, jaw agape, as they competitively counted up their tips after work. I filled out a Flamette application, leaving the “Experience” section blank, and was shown the door.

I next applied to be an A&W carhop; the manager took one look at my scrawny arms and knew that I would immediately dump a tray laden with those heavy glass mugs of root beer and ice cream over myself or a customer.

I lowered my sights to restaurant kitchen work. When we were still a family, my father had spent enough money at the Bellows Steak House that the manager recognized me as I sat in the waiting area on a June afternoon, clutching my application form. He hired me as a salad girl. I would work four nights a week and make $1.90 an hour.

My work night started at four o’clock. My primary duty was preparing the mix for the big salad that came with every dinner and that was ninety percent iceberg lettuce. In the basement prep kitchen I’d give each head of lettuce a good thunk on the bottom and twist out the core as instructed by the scary chef. He had also shown me how to operate the electric lettuce shredder without losing a finger, but I was too terrified of that whirling, deadly contraption to put a hand anywhere near it. Instead I stood across the room and tossed heads of lettuce towards the blades, again and again, gathering the bits that went all over the floor and adding them to the giant plastic salad bin.

I assembled salad after salad so that they could be delivered, cold and crisp, to diners who would smother them with French, Thousand Island, or Roquefort. It was my job to keep the tripart salad dressing servers filled; I never washed those servers, just gave them a quick wipe with a kitchen rag to clean off the crust along the sides of the silvery cups and the top of the ladles.

My other task was making shrimp cocktails, and boy, Duluthians loved their shrimp cocktails. After the eight hundred salads were made and chilling, I pulled a huge bag of shrimp out of the freezer and dunked it in a sink filled with lukewarm water. I spent the next hour peeling and deveining shrimp, stopping to pull out salads for early bird diners and hoping that they wouldn’t order the shrimp cocktail as basically they would get shrimp-flavored ice cubes.

The nadir of my night was when some brave or deluded soul ordered a platter of oysters or clams on the half shell. While unordered shrimp ended up in the next night’s scampi, the restaurant had no use for leftover bivalves, so I could not defrost them in advance. I had to struggle with each frozen shell, holding it under running water, attacking it with an oyster knife, and cutting my own hands to pieces. Then I had to slice a lemon.

Finally, towards the end of the night, with a few hateful customers lingering in the dining room trying to decide if they should have one more Grasshopper or Golden Cadillac or Brandy Alexander, the kitchen would quiet and slow. The cooks scraped black squares of pumice up and down the grill while the waitresses snuck back to my little area to grab a forbidden smoke. I was in awe of these creatures, with their elaborate updos, kabuki eyebrows and eyeliner, and pockets bursting with ones. They paid me no attention at all, I was a mere salad girl, covered in shreds of lettuce and smelling of shrimp.

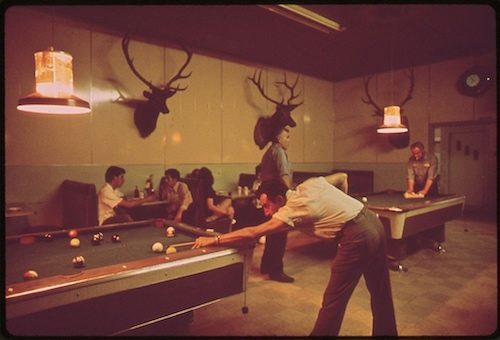

Every week I cashed my paycheck at the Bellow’s and immediately set out to buy drugs, a task that pathologically shy Michael Vlasdic had relegated to me. Even with my onerous work schedule, the freedom of summer meant that Michael and I could trip several times a week. There were kids from East High who could be counted on to have acid, my old admirer Stan now one of them. I could call John Bean; although I was always afraid that he would bring along Doug Figge, he never did. If no one I knew had LSD, I took the bus downtown to the scary, sinister pool hall, where the greasers from Central and Denfeld High hung out, a place that was so forbidden to a nice East High girl that it went unmentioned.

Fortunately, I never had to actually go into that dimly lit den of perdition. I’d poke my head in the doorway, and some long-haired guy in a white tee would nod, follow me out, and lead me to the back alley.

I hated buying drugs at the pool hall, convinced that I was going to be raped, robbed, and murdered by one of the dodgy seventeen-or eighteen-year-old dealers. I pleaded with Michael, “I’ll give you the money, but please, can you go make the buy?” Michael blanched at the idea of talking to a stranger, even one who sold drugs; but I was tired of risking my life. He reluctantly took my money and I felt like the worst girlfriend in the world.

That evening I let myself into the Vlasdic’s house. Michael was lying on the living room floor, staring at the ceiling. I shook him, “Michael. You bought acid right?” He nodded. “Ah, can I have mine?” He shook his head, pointed at his open mouth, and closed his eyes. I disgustedly left him there to trip on his own, went back home straight as a stone, and kept control of the money and the drugs from then on.

North Country Girl: Chapter 29 — A Teenager in Love

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My first date with Michael Vlasdic had a few glitches. Duluth teen culture was car culture. With your friends a car was a party on wheels. With a boy a car was a bubble of privacy, a place to make out, WEBC on low, heater on high, the windows opaque with steam. I, however, had only a learner’s permit; to get that required just a multiple-choice test on road rules, the kind of test I aced every time. I had barely squeaked through drivers’ ed, the instructor constantly taking over control and slamming on his brakes because I was unable to gauge distances between the car I was driving and everything else, other cars, pedestrians, curbs. I also had difficulties telling the brake pedal from the gas pedal. My sweating, pale instructor assured me that all I needed was more practice, but every time my mother let me take the wheel it ended quickly in shouts and tears. I was idiotically optimistic that when I took the road test in December, when I turned sixteen, I would magically pass, but for now taking the family car was verboten.

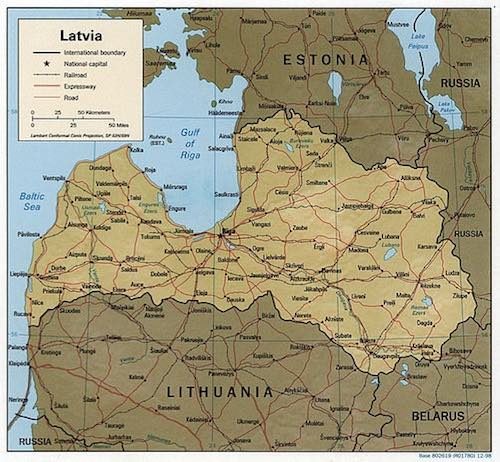

Michael Vlasdic lacked both a car and a father. His mother was originally from Latvia

(a country I knew only from volume L of my old World Book encyclopedia, which identified it as one of the Soviet Socialist Republics) and had moved to Duluth to teach German at the university. She was stately and Old World polite, with a solid-looking helmet of dark hair, and always in a boxy wooly suit, thick beige nylons, and sensible shoes. The missing deadbeat dad was in Mitchell, South Dakota; Michael once proudly showed me a postcard of a large yellow structure that proclaimed Greetings from the Corn Palace! that his dad had sent him. In lieu of money, I guess.

I had met a few kids without fathers, but a family without a car? Where could Michael and I go on our first date? You could not enter the London Inn parking lot on foot. You’d be a laughingstock.

On the phone Michael said, “Why don’t you come over here and we’ll listen to records?” I did not have a better idea, so that Saturday I walked the twenty minutes over to Michael’s house. His mother was out for the night. His mother was out a lot.

Michael and his mother lived in a small up-and-down duplex filled with books and cracked oil paintings in gilded frames, dark heavy furniture, more books, jewel-toned oriental rugs, potted plants, and more books. There was also the standard big cabinet hi-fi in the living room. Since there was no parent in the house, Michael and I went to his room to listen to music and so Michael could smoke a joint, which he did leaning precariously out the window. He offered me a hit, but I was afraid if I had my usual pot-induced coughing fit while straddling the windowsill I would plummet to the ground and that would be a hell of a first date.

We started talking, about music (we liked the same bands! Of course in 1969 every kid was devoted to Steppenwolf, Cream, Jimi Hendrix) then books (Michael had read The Lord of the Rings three times to my twice). A current of tingly magnetism drew us closer and closer together, and then there was a lot of kissing. Seated kissing, with our arms propped straight as crutches on Michael’s narrow, neatly-made bed, then lying down kissing, with arms wrapped around each other, bodies close enough together that I could feel him harden. Michael reddened with embarrassment, got up to take off his glasses, and we kissed some more.

Time played its elastic tricks: it stopped while we were kissing, then hurried forward, the clock rushing to eleven, my curfew, and I had to leave, with still the twenty minutes to walk home. Michael and I untangled, he found his glasses, but it was impossible for us to part. He walked me back to my house, through the still and silent streets, a thousand stars on a moonless Minnesota night twinkling down at the new lovers. Michael was bookish and shy, a proto-hippie like me, and charmingly unaware of how good-looking he was. On that walk we shared what secrets and history sixteen- and fifteen-year-olds could have accumulated. We marveled that the universe had contrived to bring us together, two pieces fitting into place in the cosmic jigsaw.

We kissed as long as possible in front of my house; I was just beginning to put the horrors of July 21st behind me. If my mother should have appeared in the doorway and started yelling, I felt I would die. I pushed Michael away, slipped into my sleeping house and floated up the stairs. In bed, I wrapped my arms around myself, imagining it was Michael who held me, I thought of the dirty books hidden away underneath me; the pages I had carefully dog-eared didn’t begin to describe the sweet ache I felt, a longing I knew Michael felt too. I wondered how long it would take us to go all the way.

It took a week. The following Saturday, up in his room, his mother attending another university faculty beanfest, our clothes half off and “Whole Lotta Love” urging us on, Michael told me he loved me. “I love you too,” I said, and it turned out those really were magic words, words that made it imperative that we get rid of the rest of our clothing immediately. It was Michael’s first time and I wished it were mine too. “Making love” and “having sex,” are such awful phrases for what we did. We were two young animals, playful, tender, funny, considerate, with wildly responsive teen-age bodies we smashed together as closely as possible. It was as if the two of us had invented sex, sex that was as transcendent and addictive as any drug.\

Adorable, innocent Michael did not have a condom, since he was even more unwilling than I was to go into a drugstore and ask for a package of rubbers, which in those days were kept locked up on a high shelf in the back of the storage room to extend the embarrassment of the foot-shuffling, eye-averting teenage boy waiting at the counter. (One particular wisenheimer druggist liked to yell out, “What size, buddy?”)

After our first time, I called an emergency sex consultation with my girlfriends, held in Linda Laurence’s basement. While taking sips from Linda’s parents’ collection of Bols after-dinner drinks (crème de menthe, crème de cocao, peach brandy, cherry kirsch, and other stomach-churning flavors) and everyone but me smoking cigarettes, we discussed how I could have as much sex as possible without getting pregnant. Alternative methods were suggested and met with peals of laughter, some real, some forced; these ideas were quickly discarded. Some of my gang did have boyfriends who braved the druggist’s stink-eye and the wait of shame at the Tru-Value Pharmacy, but you don’t ask your boyfriend if he can spare a rubber so some other guy can get laid.

We pooled our collective knowledge and misinformation about the female reproductive system. Linda plucked a calendar off the wall and we huddled over it, guessing at those days that might be safe and days I should definitely keep my panties on.

Pregnancy was the dark looming cloud that hung over rapturous teenage sex: everyone knew of the senior girl who had been sent off to a home for unwed mothers, returning after six months thin and wan and without a baby or a boyfriend. But despite regular scares, no one in our gang got pregnant or had any tragedy befall us. While we had scrapes and accidents, heartaches and breakups, for the three years of high school we lived in a teen fairyland, where we could have sex and not get pregnant, drive drunk in cars with no seatbelts without going through the windshield, and hop on and off moving freight trains without losing a leg.

Besides being considerate enough to go out almost every Saturday night, Mrs. Vlasdic thoughtfully taught class two afternoons a week. If it were the right day of the month Michael and I would dash from school to his house for the world’s quickest quickie. When Mrs. Vlasdic walked through the door at four o’clock, she’d find Michael and me at the dining table, fully clothed, surrounded by homework, and drinking tea. She had to have known what was going on.

My own parents had briefly met Michael and felt no reason to be alarmed: his mother was a university professor and Michael seemed too painfully shy and nerdish to be any threat to my already sullied honor. And at that point, my family was spinning apart.

After buying the big, impressive Hawthorne Road house, my dad spent less and less time there. My mom was taking a full-course load at the university, her youthful dreams of being an actress whittled down to a prospective career as a speech therapist. My younger sisters Heidi and Lani would have been latchkey kids, except we never locked our doors in Duluth; after school they walked the three blocks home together, let themselves in, and headed straight for the TV.

But even at its emptiest, my house was firmly off-limits for sex. I was haunted by the horrifying memory of Doug Figge trying to cover his balls with his hands, like Adam suddenly aware and ashamed of his nakedness. I wouldn’t feel safe having sex in my own home if both my parents were in Idaho.

On the Saturday nights Mrs. Vlasdic selfishly stayed home, we hopped in a car driven by Roger or Needle, Michael and I clutched together smooching in the back seat. We’d drive around Duluth for hours, the guys smoking pot or searching for someone to sell them pot.

I luxuriated in my membership in two high school groups: my gang of loyal, funny, raucous girlfriends, and the druggies of East High, whose numbers increased daily. We proclaimed our allegiance to the counterculture with long hair, fringed jackets, wire-rimmed glasses, beads, and bellbottoms. My pal Wendi Carlson became a fervent pot smoker and made it her life’s mission to teach me to inhale. She was even more disappointed than I was that I was still unable to draw the tiniest puff inside my lungs.

A member of the druggies was cute Stan Lewis, a year behind me, who showed up at all the parties with weed. Stan and I would find each other at these parties and swap what little we knew about psychedelics. Could you really get high from morning glory seeds or nutmeg? What was the difference between LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin? When you’re tripping, do you need someone straight around in case you freak out? How much did these drugs cost and where could we get them? I thought of Joe Sloan, who would soon be back in Duluth for Christmas, which reminded me of Doug Figge and the astronaut, so I lied and told Stan I didn’t know anyone who had those kind of drugs.

Stan, a determined guy, went out and found someone who did, and for my sixteenth birthday he gave me a small blue pill that he said was mescaline, supposedly not as mind-blowing as LSD. He handed it to me in the parking lot of the London Inn. I immediately popped that pill in my mouth, washed it down with watery Coke, and thanked Stan with a friendly kiss on the cheek, which I now suspect was not what he was hoping for. I jumped into the White Delight on to Wendi Carlson’s lap and whispered in her ear what I had just done.

There were no empty houses that night so my sixteenth birthday celebration was a three-hour auto tour of residential Duluth with six of my best friends. It was early December, pre-broomball season, but there were frequent stops for peeing in the snow and return visits to the London Inn to see if any cute boys were around. Wendi kept pinching me hard and asking, “Are you tripping yet? How about now?” and I kept shaking my head no.

I was somewhere around Hawthorne Road, on the edge of my front lawn, when the drugs began to take hold. I was sober as Judge Erman when I climbed out of the White Delight and headed into my house; I had not a single drink on my birthday, waiting for the mescaline to kick in and transport my mind to Peter Max world.

Just as I was thinking that poor Stan had been swindled, I opened the door to my house and was blinded by the hot-as-the-sun kitchen lights. I stumbled and braced myself up on the wall, which was wildly tilting, while a galaxy of neon geometric shapes swirled around me. It took me a minute to realize that the low frequency rumble I was hearing was my mother asking me how my birthday was. I slid into the living room doorway and made small talk to the elongated monster with snakes for hands that was sitting on the TV couch. I finally escaped and made my way up to my room and tripped for hours, staring out into the night, where twinkling snowflakes and yellow streetlights and the deep blue of winter created a hypnotic tapestry. I twirled the dial of my melting bedside radio, WEBC having signed off for the night, searching for music and unfortunately hit on a horrible station out of Chicago that chose to play “D.O.A.” by Bloodrock at 2 a.m. I listened to the whole thing, perched on the edge of madness, switched the radio off, and hid under my blanket until I stopped hallucinating horrible, bloody car wrecks and finally fell asleep.

I couldn’t wait to trip again.

North Country Girl: Chapter 28 — The Age of Aquarius Comes to Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I didn’t tell Doug Figge about Wendi Carlson’s advice, that the key to enjoying sex is more sex. I didn’t have to. His mind was on the same track, the only track 17-year old boys’ run on, the track with the thundering locomotive of sex hurtling along, blowing all other thoughts away.

The day after the first man landed on the moon and I gave up my virginity, Doug called with the woeful news that Joe Sloan had emerged from his basement with powder burns and a singed shirt, accompanied by a powerful stink of cordite. His parents decreed that their house, including those forgotten bedrooms, was off limits.

Doug knew it was one of my mother’s class days. “Please, please,” he begged. “Let me come over. It will be okay, we’ll be quick,” he said as if that were a selling point. “Fine,” I sighed.

One of the things I learned from my first experience was that sex was messy, and should not take place on my mother’s ivory brocade French Provincial couch. Doug pulled into my driveway, I let him in the backdoor, and hurriedly escorted up him to my bedroom.

It was the middle of the afternoon and the sun streamed through my windows. I was shy about taking off my clothes in the summer glare, and not especially looking forward to seeing my fairly unattractive boyfriend naked either. I turned my back, stripped and slipped between the sheets, and there was Doug, nude and on top of me and ready.

I thought we were safe. My mother usually wasn’t home till three. But some vagary of the University of Minnesota’s college calendar or maybe the excitement of the moon landing had caused my mother’s class to be canceled that day. I heard a familiar car pull up to the house and thought “This is bad this is bad this is bad,” and tried to shove Doug off me. His eyes were squeezed shut, beads of sweat popping out on his wispy moustache; he was oblivious. “Doug Doug Doug,” I whispered hoarsely, as I heard the house door open and not only my mother’s voice, but my sisters’ as well. I pushed him harder and finally got him off me and he realized that my mother was home.

As Doug’s Corvair was in the driveway, my mother knew we were in the house alone, which she had strictly forbidden fearing exactly what had come to pass. Before Doug and I had a chance to find even our underwear, my mother flung open my bedroom door and lost her mind. She didn’t know whom to hit first. She whacked Doug about the head a few times, as he tried to find his jeans, the hell with his briefs, then she turned on me, as wordless as a banshee, unable to articulate what she had seen with her own eyes: her fifteen-year-old daughter having sex. I burst into tears and Doug made his escape.

That event is burned into my memory with almost a physical pain. I can feel the warm air coming in through the windows, pushing the sheer white curtains into the room. I can hear the torrent of my mother’s shrieks, and my entire body burning and blushing and trying to vanish into thin air. Out of the corner of my eye, while trying to duck my mother’s roundhouses, I see a blur that is Doug, holding his shirt and shoes, rushing down the stairs and out of my life.

A sadder but wiser fairy had come to undo one of my wishes, a wish that had gone horribly wrong. I no longer had a boyfriend. My mother forbade me to see Doug Figge ever again.

When I told Wendi Carlson about that shameful, sordid experience, she burst into peals of laughter, which shocked me into learning an important lesson: if your good friend cracks up at your sad story, it’s not the tragedy you think it is.

Egged on by Wendi, I held my gang of girlfriends spellbound for the remaining weeks of summer with the gripping tale of my mother catching me in bed with Doug Figge. “Tell it again!” they’d squeal, as we sat by a bonfire or dangled our legs in the water off a lakeside dock. I’d get to the point where Doug tore bare butt down the staircase, and they’d roar, squirting beer through their noses. Every time I re-told that tale of horror, it became less real, more like something that happened to another person.

“You need a new boyfriend!” cried Nancy, Wendi, and all the other girls. I wasn’t sure that I did. My romantic history consisted of a single date with Wesley Baggot, being publicly dumped by Steve LaFlamme, a forced make out session with a candidate for a skin graft, and having a boyfriend for six months that I didn’t really like and who never took me out once on a real date.

If I was going to have another boyfriend, I was going to pick him out myself. No more waiting passively for some boy to choose me; I had enough of that during those nightmarish ballroom dance classes. From now on, every day was going to be Sadie Hawkins Day.

I rejected all the efforts my pals made to fix me up. I studied the eligible guys in the packs that hovered around us, looking in vain for potential boyfriend material, someone who was good-looking and smart and funny. My imaginary future boyfriend had to go to East High, so he could hold my hand in the halls and take me to a school dance. I was through with boys who went to weird other schools, unless Joe Sloan reappeared.

Maybe it was this gritty new determination, maybe it was getting rid of my virginity at fifteen-and-a-half: I grew a backbone. I found I could talk, and laugh, and flirt with boys, ignoring the voice in my head that told me I sounded like an idiot.

Now I needed to shed my gawky nerd look, my face hidden behind those oversized tortoise-shell spectacles with the Coke bottle lenses. My mother was still not talking to me, just shooting me looks that alternated between disappointment and disgust. I turned on my father at every occasion, begging for contact lenses. Dad preferred that I remained unattractive; he didn’t know that the worst had already happened. My eye doctor won the argument for me, pointing out to my father that contacts would slow down my eyes’ deterioration to Mr. Magoo-level near-sightedness, and eliminate the need to buy new and thicker glasses every year. I got my contacts and I promptly lost one in our gold shag carpet. So much for my dad saving money on my eye care; it was back to the doctor to order another $30 contact. Now both my parents were mad at me.

Who cared about parents when there was a potential boyfriend somewhere out there, a boyfriend who could now gaze directly into my green eyes, while stroking my hair. I hadn’t allowed a scissor to come near my head for months and my hair now flowed halfway down my back, an unremarkable brown, but thick and shiny with youth and health, perfect hippie girl hair. I also decided to stop letting my mother pick out my clothes. During our annual shopping trip to Minneapolis I ditched my mom and sisters in Dayton’s Back to School section and found an incense-smoky store where I bought a purple leather fringed jacket, a collection of gauzy Indian shirts, and embroidered bell bottom jeans. Suddenly instead of a four-eyed geek with a bad haircut, there was a cute girl in the mirror. My third wish, a wish so improbable and so desperate that I had never consciously acknowledged it, had been granted.

***

Late in August Walter Cronkite reported that thousands upon thousands of hippies had descended on a farm in upstate New York for a three-day music festival. The six o’clock news never showed any of the music, only the miles of traffic and abandoned cars and then finally half-naked people rolling about in the mud, Walter tut-tutting away like a maiden aunt. It looked amazing, the most fun a teenager could have. I watched desolate, knowing my tribe was out there, listening to the music I loved, taking the drugs I wanted. As always, life was happening somewhere else.

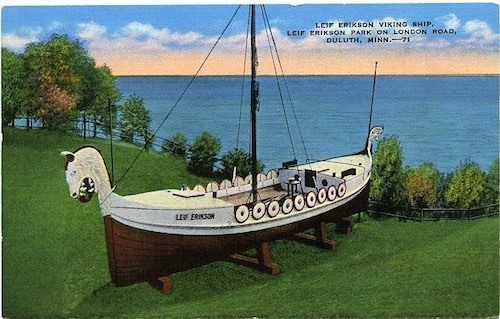

But Woodstock unlocked something in the teenagers of Duluth. As if summoned by the Pied Piper, throngs of kids coalesced in scraggy bands on the rolling green lawns of Leif Erickson Park, boys strumming guitars and girls twirling their long gypsy skirts around and around. At the downtown Woolworth’s next to the turtle tank I found a rack of buttons with peace symbols and “Make Love Not War” that I pinned on the lapel of my fringed jacket. The Age of Aquarius had reached Duluth.

On the first day of school, I walked down the East High hall into a different world. A whole subset of druggies and hippies had sprung up like dandelions. There were dozens of kids in tie-dye, patchouli oil was used way too liberally, and almost every boy, including the jocks, had hair that brushed the collars of their shirts.

I made my way up to the third floor, to Mr. Burrows’ two-hour, buttock-killing, smart-kids-only, enthralling American History and Literature Class, an educational jewel that was more fascinating and more informative than any college course, even if it did hew to the Famous White Men model, with nods to Anne Bradstreet and Emily Dickenson. As I slipped into my usual seat next to Nancy Erman, she nudged me, nodded her head sideways, and daringly whispered “New boy. Your type.” Mr. Burrows’ thundering brow turned toward Nancy at this violation of his rule of absolute silence. She gave him a twinkling Nancy smile, and, mollified, Mr. Burrows went back to the chalkboard to write: “A true relation of such occurrences and accidents as hath hapned in Virginia. John Smith, 1608,” and we were off to the races, three hundred years of history and literature to cover in nine months.

I snuck a glance in the direction Nancy had nodded in. Sitting all alone against the back wall, lit like a Renaissance angel under the slanting autumn light that poured in through the diamond-paned windows, was a boy with long dark hair that reached his shoulders and John Lennon wire-rimmed glasses. Beneath the glasses and the hair was a cherubic face, as round and sweet as an apple, a face that wore a serious, studious expression that reminded me to turn, reluctant and hopeful, back to my own interrupted note-taking on the founding of Jamestown.

This boy was Michael Vlasdic, my first love.

He was heart-meltingly handsome, and I knew that he had to be smart to be in Mr. Burrows’ advanced class. Two hours later, when Mr. Burrows allowed questions and comments, Michael sat silent, although I did see him occasionally smile, revealing adorable dimples that would be so much fun to kiss.

Michael Vlasdic was also in my lunch period, where I clocked him sitting at the back of the raucous East cafeteria with Roger Dennison, another rare new kid, who was good-looking in a blond, high-cheeked, Slavic way despite a nose like a jagged ski run, and with my old friend Eric Olson from elementary school. Eric was now known as Needle, not for his use of intravenous drugs but for his extreme skinniness. Roger and Needle both sported nicely shaggy hair, though not as long as Michael’s.

A year ago, I would not have been able to walk within ten feet of a boy I liked without my stomach flipping over and my tongue gluing itself to the roof of my mouth. But good luck and bad experiences had given me confidence. I had shed my virginity and my goofy glasses and I had Michael Vlasdic in my sights.

The new, sophisticated me plopped down uninvited among the three boys, making sure that I was next to Michael, and finally put my mother’s advice—“Just walk up to a boy, say hi and start talking”—to the test. I smiled, asked Roger where he was from (Colorado, his father worked for the Air Force and had been transferred to Duluth’s tiny base), talked to Needle, another smarty pants, about our classes, and finally turned to Michael and said “I like your glasses.”

I watched his face and my heart gave a small thump. I thought, I know this person, I have been this person, struck dumb at the prospect of talking to the opposite sex. It was as if I could read what was going through Michael’s mind: “What does that mean? Is she making fun of me? Or should I say thank you and then say I like your shirt?” I could tell he was weighing all his options as if one wrong word could open up the cafeteria floor and send him down to Hades, while the other kids laughed and pointed at him.

It was too painful. I jumped back in and carried the conversation single-handedly (look mom!) until the bell rang to send us off to class. That was also my signal to make my move. “So Michael,” I said, “What are you doing Saturday night?” All three boys exchanged shocked, mystified looks, but there was none of the horror that I used to see on the faces of the boy I asked to dance at Cotillion.

Michael quietly admitted that he had no plans for Saturday night and then looked as if he were waiting for a stinging, “Oh I’m going to a fun party” from me.

I took a breath and said, “Do you want to go out, go do something?” A beatific smile crossed Michael’s face, revealing those adorable dimples that I could have kissed right there and then. I took this as a yes. We scribbled phone numbers in each others’ notebooks and I left feeling that little squeeze of my heart and tingling between my legs that I got listening to Robert Plant moan “The Lemon Song” or re-reading the dog-eared pages in my copies of Lolita and Candy that I hid between the mattresses.