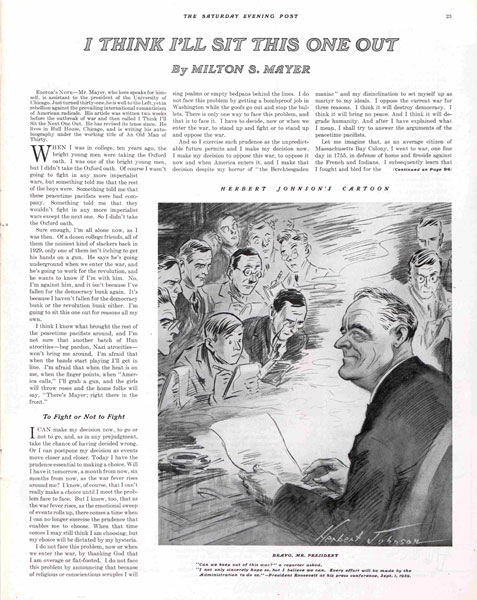

A Bad Choice for Spokesman

In the days to come, the Post editors must have regretted ever hearing of a young man named Milton S. Mayer

The editors had been looking for contributors who supported the magazine’s isolationist views when war broke out in Europe. Like many Americans, they regretted U.S. participation in the last war, in which the country lost thousands of young men but gained neither wealth nor territory as our European allies had. Worse, the war had only increased enmities among the nations of Europe. Moreover, our allies were not paying back the war loans America had extended them.

Now, with unemployment still hovering around 18 percent, and the U.S. economy still trying to shake off the Depression, the editors wanted to concentrate on America’s problems — which meant staying out of the war.

Milton Mayer also opposed the war, but for quite different reasons, which he presented in the article “I Think I’ll Sit This One Out.” Read the entire article “I Think I’ll Sit This One Out” by Milton S. Mayer from the October 7, 1939 issue of the Post. The editors included it in the October 7 issue, with the statement that Mayer spoke “for himself.” He also happened to be supporting the Post’s isolationist viewpoint. I think the editors agreed with him so strongly that they overlooked the fact his article was filled with groundless claims and sweeping generalizations.

He was an unlikely contributor: a 31-year-old student at the University of Chicago, though he was still on probation, he told a Post interviewer, for throwing beer bottles out his dorm window several years before. He had never lived outside the U.S. and had no experience of the situation in Europe. His sole recommendation as a contributor was his antiwar stance.

Mayer opposed any involvement in the war for three reasons. “I think it will destroy democracy,” he wrote. “I think it will bring no peace. And I think it will degrade humanity.”

Well, he had a right to his opinion. But normally, the Post wouldn’t offer opinions that weren’t backed by some research or personal experience. All Mayer could offer was his faith in his own wild assertions, such as—

• Defeating Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918 had resulted in Hitler’s coming to power. Therefore, if America defeated Hitler, another tyrant — even more brutal than Hitler — would take his place.

• England wasn’t worth defending because it would betray any ally to buy peace with Hitler.

• Many of the leaders who’d been deposed by Hitler weren’t strong advocates of democratic rule, hence not worth helping.

• Intolerance and fascism rose sharply in America after World War I. So it was bound to happen after the next war.

To all these assertions, he offered neither argument nor evidence.

All wars were bad, Mayer believed: “War makes ‘madmen’ of us all, and no balance of power that was ever devised remained in balance very long. For the victor grows fat and the vanquished grow lean, and the time comes when the vanquished have to fight and see their chance.”

To be fair, most of history up to 1939 supported Mayer’s statement. He couldn’t have known that when World War II ended there would not be another Hitler. Germany would not start another war for European conquest. France, Belgium, Great Britain, Germany, and the Scandinavian nations would enter a peace that has endured for almost 70 years. And America’s two greatest adversaries became strong postwar allies.

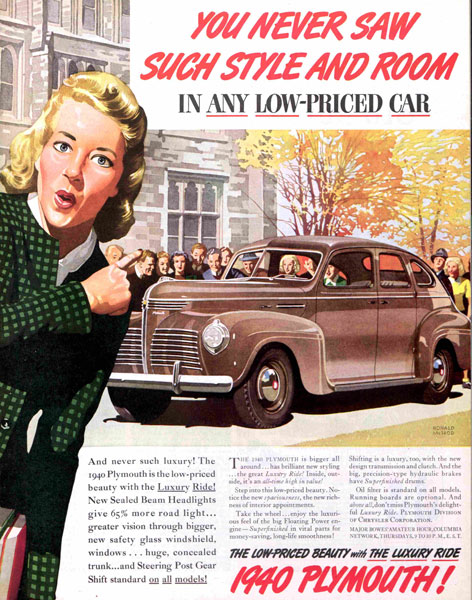

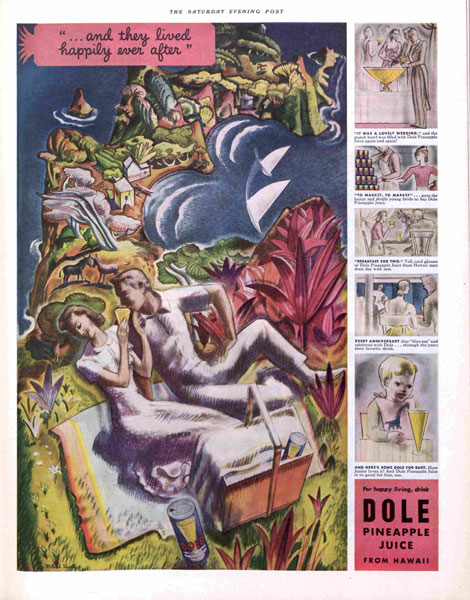

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: