July 1 through History: A Day of Rules and Measures

With a limited number of days on the calendar, many events across the broad spectrum of history happen to share a date. Sometimes the pairings are fraught with irony, like when John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died on the same day … which happened to be the Fourth of July. Other times they’re interesting coincidences, such as all of the meaningful events that happened on April 30 over the decades.

July 1st might not be the “biggest” day in history, but it happened to be the landing zone for events that affect your everyday life. In 1959, 1963, and 1984, the first day of July saw changes to numbers and rules that have a bearing on how you measure, how you mail, and how you go to the movies.

July 1, 1959: The Agreement on International Measurements

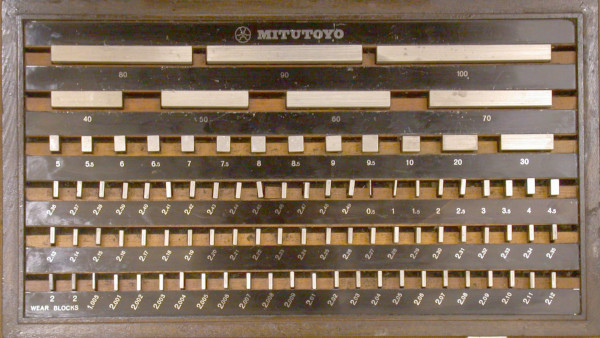

The definitions for weights and measures typically come from a physical object called a standard. A standard for one pound, for example, would weigh one pound. Disaster struck in 1834 when the Palace of Westminster in England, the home of British Parliament, burned; among the things destroyed by the blaze were the physical standards for weight and length. New versions were made, and in 1855, the

United States adopted that new British ruler for feet and yards.

The next several decades saw updates and additions that were generally agreed upon by the United States, England, and other countries associated with the British Commonwealth. By 1903, American physicist Albert Michelson’s experiments in electromagnetic waves proved that you could set defined lengths using light waves. Over the next few years, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures would accept the light-wave definition of the meter; by 1935, 16 countries had taken on the light-wave inch (25.4 mm) as the “industrial inch” standard.

Things got even more precise as scientists and standards bodies from around the world began to consider atomic measurements. The U.S., the U.K., Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa agreed upon a specific “international pound” and “international yard” in 1958. The new definitions placed the 3-foot yard as equivalent to .9144 meters, and the pound at .45359237 kilograms. On July 1, 1959, the U.S. National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology) officially approved the system.

Today, only three countries have not adopted the metric system for everyday use: Liberia, Burma, and the United States. The other 192 countries on Earth use it for everything. However, the U.S. does commonly use the metric system in the fields of science, medicine, and a number of other industries (including firearms manufacturing, gemstones, and energy).

July 1, 1963: ZIP Codes Come to America

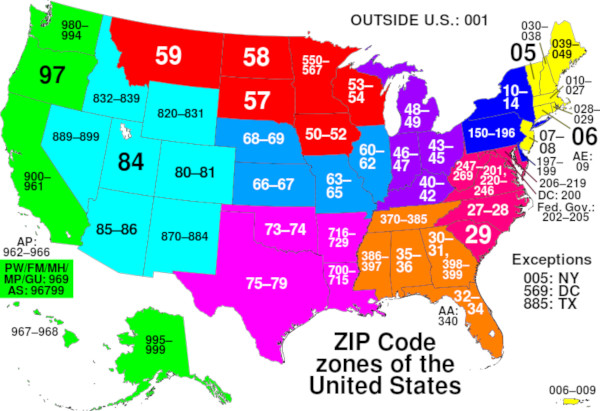

Introduced on this date in 1963 with the hope of improving mail delivery speed and efficiency, the ZIP (Zone Improvement Plan) code was the brainchild of postal inspector Robert Moon; he proposed a three-digit postal code in 1944. The first digit represents your region of the country (0 is the East Coast, 9 the West Coast), and digits two and three stand for an SCF or “sectional center facility”; that’s the place where mail is sorted for a certain area. The Postal Service added the final two digits to the code to provide more specificity, routing the mail to the proper post office for delivery. A second big change came to the mail on October 1 of that year, when the two-letter state abbreviations were introduced.

ZIP codes got an upgrade in 1983 when the “ZIP+4” debuted. The extra four digits are intended to get very specific, sometimes representing a single building within the area defined by the first five digits. The most famous ZIP code in the United States is likely 90210, the code for Beverly Hills; BH90210, the third TV series to bear the well-known numbers, begins on August 7 on Fox.

July 1, 1984: The MPAA Releases PG-13

The infamous Gremlins kitchen scene (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips)

Blame it on the Gremlins; well, Gremlins and Indiana Jones. The Motion Picture Association of America introduced the modern film ratings system in 1968; after a couple of years of tinkering, the system settled on G (General Audiences), PG (Parent Guidance suggested), R (Restricted, no one under 17 admitted without a parent or guardian), and X (no one under 17). In 1984, however, two Steven Spielberg-related films pushed the envelope on violence at the cinema. The Spielberg-directed Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom showed a beating heart being removed from a man’s chest, while the Spielberg-produced Gremlins featured a number of gross-outs, including the famous kitchen massacre scene. Complaints and controversy arose over the two PG films, and the MPAA’s solution was to introduce a new rating as a middle ground between PG and R. The PG-13 rating represents the idea of “Parents Strongly Cautioned,” meaning that there is likely to be more violence, swearing, or limited nudity than one would expect in a PG film. The first movie to carry the rating was John Milius’s Brat-Pack-vs.-the-Soviet-Union actioner Red Dawn.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Five Scandalous Film Rating Controversies

Sex and violence. Foul language. Gore. Socially unacceptable behavior, including the glorification of criminals. Dark subject matter and gallows humor. In others words, a good time at the movies.

But what might be a good time for one person might be a little too much blood and guts for another. How’s a moviegoer supposed to know what they’re in for?

For years, different offices and local review boards tried to apply different standards and rules to acceptable content in motion pictures. This was in addition to a strict Motion Picture Production Code. Fifty years ago, the Motion Picture Association of America tried to take the reins and codify a system that could be employed across all of the film.

That became the modern MPAA film rating system — the G, PG, PG-13, R, NC-17, and X ratings we all know and love (or hate) today.

The Motion Picture Production Code debuted in 1930 from the MPAA’s forerunner, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. It applied a number of standards that might be considered humorous today, including a three-second on-screen-kiss time limit. By the 1960s, the envelope was constantly being pushed by young directors and foreign filmmakers, a need to separate what was available on film versus what was widely available on television, and an audience that had become more sophisticated about adult themes that had once been considered off-limits for film].

The MPPDA had evolved into the MPAA in 1945, and by the late 1960s, its president, Jack Valenti, knew the old code was out of date; he went so far as to say that it had “the odious smell of censorship.” With a goal of acknowledging “the irresistible force of creators determined to make ‘their films,'” and to avoid “the possible intrusion of government into the movie arena,” the MPAA created a new system.

The original version from 1968 contains four ratings: G (General Audiences); M (Mature audiences with parental guidance suggested); R (Restricted, no one under 16 without a parent or guardian); and X (no one under 16). That was tinkered with over the next two years, with some age adjustments (the 16s were increased to 17) and M being changed to GP and then PG. By 1972, the system was G, PG, R, and X, and it would remain that way for years. That makes it a great place to stop and examine five scandalous film rating controversies.

1. Midnight Cowboy Gets an X and Three Oscars (1969)

The Midnight Cowboy trailer.

Midnight Cowboy courted controversy right from the start. Based on the novel by James Leo Herlihy, the John Schlesinger-directed film drew the attention of the ratings board for its frank depiction of sex, male prostitution, and themes of homosexuality. Though initially granted an R, executives at United Artists decided to accept an X; according to Tino Balio’s book, United Artists Volume 2, 1951–1978 : The Company That Changed the Film Industry, the studio made the move after being advised by a psychologist that the film could be a “possible influence upon youngsters.” The X didn’t stop the film from being critically acclaimed; in went on to take Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay (for writer Waldo Salt) at the 1970 Academy Awards. In a bit of irony, when the age ranges were moved in the 1972 MPAA ratings change, Midnight Cowboy was reclassified an R and has retained that rating since.

2. Steven Spielberg and Friends Force a New Rating (1984)

The Red Dawn trailer, featuring the first PG-13 rating “green screen.”

Steven Spielberg was the undisputed King of Hollywood in 1984. He’d already directed future classics and huge hits like Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T., and produced the hit Poltergeist. In 1984, he’d direct the Raiders sequel Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and produced Gremlins. Temple and Gremlins both carried PG ratings, which left a number of parents concerned when the saw the films with their kids. Temple featured some significant violence, including one scene where a man’s still-beating heart is removed from his chest; Gremlins featured a number of gross-out special effects and Phoebe Cates’s infamous monologue about the death of her father (while trying to surprise her while dressed as Santa, he attempted to climb down the chimney, became stuck, and died, leading to the young girl learning that there is no Santa). When the MPAA looked at the ratings in light of the complaints, they the challenge of determining what might be appropriate, considering that the definition of what was okay could be unique for different parents and different children. Spielberg himself suggested an intermediate rating between PG and R, and the result was the MPAA’s creation of PG-13. PG-13 came with the verbiage “Parents Strongly Cautioned – some material may be inappropriate for children under 13,” and it was first applied to John Milius’s Red Dawn later that year.

3. X Gets Replaced (1990)

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert fiercely criticized the MPAA in their review of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer from their program Siskel & Ebert & The Movies in 1990.

During the independent film boom of the late 1980s and the early 1990s, it became apparent that the MPAA had a X rating problem. A lack of copyright for ratings allowed any producer of pornography to apply an X rating to their film, leaving no distinction between an artistic film that might push boundaries and a pornographic work. This problem came into sharper focus with the production of three challenging films: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1989), The Cook, The Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover (1990) and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990). All three films were released unrated because the MPAA declined to rate them lower and the studios would not take an X rating, given its association. Mainstream theatre chains were also declining to show films with an X, severely limiting the film’s opportunity to be seen and make money. This left a void for movies made for adults that dealt with graphic violence (as in the case of Henry) or frank depictions of sexuality (as in the other two). A new rating was proposed; NC-17 meant “No Children Under 17 Admitted.” The first film to be released with the new rating was Henry & June, Philip Kaufman’s adaption of Anaïs Nin‘s book about her affair with author Henry Miller and his wife, June. In 1996, NC-17 was revised to mean “No One 17 and Under Admitted,” effectively raising the bar of admission to age 18.

4. Clerks Talks Dirty (1994)

The original trailer for Clerks.

This was a first: a film that almost drew an NC-17 rating for language only. Such was nearly the fate of Clerks, the debut film from New Jersey writer-director Kevin Smith. Smith sold part of his comic collection to raise the $27,000 he needed to make the film, a black-and-white comedic look at one long day in the lives of two twentysomething shop clerks. The outrageous humor and pop-culture-fueled dialogue made it an audience favorite and an award-winner and nominee at Sundance, Cannes, and the Independent Spirit Awards. When the film was acquired by Miramax for distribution, it got slapped with an NC-17 solely for the language; the film features almost no violence and no nudity. Famed attorney Alan Dershowitz represented Miramax on appeal, and the film was released with an R with no changes.

5. South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut Fights the MPAA Six Times (1999)

The original trailer for South Park: Bigger, Longer, & Uncut.

South Park courted controversy for its crude humor from the moment in debuted on Comedy Central. When a film version was announcement, everyone expected there to be some wrangling the MPAA. No one expected that the film had to be reviewed six times by the board before it would be granted an R rating. The process ran up until two weeks before the film was due to be released. South Park co-creator and director Trey Parker expressed his incredulity to The New York Times at the time; he noted that there was no discussion of the violence in film, saying, “The ratings board only cared about the dirty words; they’re so confused and arbitrary.” The film went on to be a huge hit and earned an Academy Award nomination for the song “Blame Canada.”