North Country Girl: Chapter 31 — Goodbye Father, Hello Mr. Chips

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

That day skiing those pristine slopes was magic. But even when real magic touches us, it is as ephemeral as a snowflake. The clock strikes midnight, the three wishes are gone, the genie put back in the lamp, the heroine awakes from what was only a dream.

Before the four o’clock winter violet had darkened the Lutsen ski slopes, Nancy and I were on the bus headed back home to Duluth. As soon as the door slammed behind me, my mother herded me into the breakfast nook, where Heidi and Lani were waiting. She seemed strangely calm, dead-eyed, like a pod person of herself.

“Your dad called. He’s coming by tomorrow to pick up some things and then he’s moving out to a place of his own.” My parents were breaking up. Lani ran off howling, “I hate you I hate you!” and locked herself in her room for three days. Heidi, who was six, shrugged this off as impossible, a silly story, and went back to watching television. Heedless of everyone else’s feelings, I pondered what this meant for me.

Back then, grown-ups and kids led such separate lives that I had no idea this was coming. My father had always been a shadowy presence, making himself known only when something unpleasant was required, forcing me to go to Sunday mass, mow the lawn, or eat those disgusting Brussels sprouts. I only noticed that my father had lately been absent for a good many evenings because Kentucky Fried Chicken and take-out London Inn cheeseburgers appeared regularly on the menu, when for years they had been a rare, delectable treat.

Encased in my own adolescent self-centeredness, I had given no weight to my mother’s sudden interest in going back to college. I assumed she was bored with delivering toothbrushes to rural schools with the Women’s Dental Auxiliary, cooking that damn meat, potato, and two veg dinner every night, and removing sharp objects from my sister’s hand.

It occurred to me that with one parent gone and the other replaced by her pod person, I would have even less supervision than I already enjoyed. I could stay out later, come home drunker or higher.

By the time I returned from school the next day my dad had come and gone. I don’t know exactly what he took from our house besides clothes and cufflinks; nothing at all was missing. It was as if he had never inhabited that big fancy house.

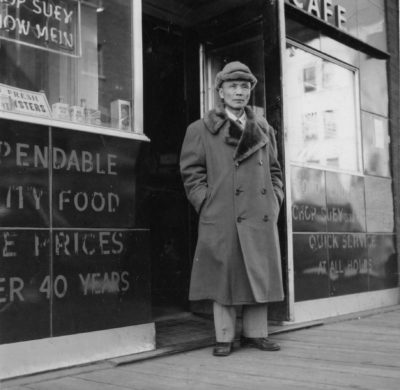

My dad moved into a crappy, barely furnished apartment in a shoddy building erected practically on top of busy London Avenue. It looked like the kind of place you went to score drugs. My one and only dinner there was punctuated with honking horns and screeching wheels and perfumed with car exhaust. We perched on wobbly folding chairs, eating take-out Chinese from Joe Huie’s off of paper plates. Through the doorway I saw an unmade bed, close enough to toss an egg roll on. I noticed there was no TV and wondered what my dad did when he wasn’t filling teeth.

After the “How’s school?” “Fine,” we ate in silence for a few minutes. Then my father began talking, and for once he wasn’t giving me an order. When he was sixteen, the same age I was, he and a buddy had traveled by freighter to Europe, where they spent most of their money on two bicycles, then headed off to explore, sleeping rough, drinking wine, eating at cheap cafes, and having adventures. “I thought my whole life would be like that, traveling, seeing the world,” he sighed. I shoveled in my fried rice, thinking, that does sound great. I felt a new type of longing, wanderlust, which made my feet prickle and my imagination soar: I pictured myself in a miniskirt in London, a beret in Paris, a toga in Athens.

My dad was still talking, interrupting my daydream.

“But first there was college and then my dad insisted I go to dental school. That’s where I met your mom.”

Somehow I knew that already, as I knew about the unplanned and unwanted — but back in 1953, the un-abortable — pregnancy that resulted in me. My birth had derailed my mom’s college education and crushed my dad’s dreams of exotic journeys. For the past sixteen years, the most exciting events in his life were madcap dental conventions and family car trips undertaken with no hotel reservations.

After years and years of being stuck in Duluth, staring down people’s mouths, my dad in true 1960s style, was going to drop out. He would cross the Pacific on a schooner, hike the Alps, go spear fishing in the Keys, eat strange spicy food at questionable restaurants in dusty Central American towns.

He had me mesmerized; I too was dying to get out of our tiny insular town and run off to Haight-Ashbury or a commune full of sex and drugs. Maybe, I thought, maybe dad will take me with him to Europe or back to Mexico. My imagination now pictured me in a Parisian beret, dad next to me in a big glittery sombrero.

When my mom came to pick me up, he gave me a fatherly pat on the back, as affectionate as a Minnesotan gets, and for a ridiculous moment I felt everything was going to be fine.

I don’t know whether my dad was lying to me or to himself. The next week my mother took me aside to confide they were definitely getting a divorce, as my father had impregnated his fat nineteen-year-old assistant, Donna. Either even adults were too embarrassed to buy rubbers or Donna was too stupid or too wily to go on the pill.

My dad was not going island-hopping in the Caribbean; he had sentenced himself to more years of diapers, tantrums, and runny noses.

I was still unsure of my filial feelings — did I feel sorry for my dad? Was I mad at him? — when we had an unexpected visitor. My paternal grandfather, who never left Carlton except to shoot an animal or catch a fish, appeared in our living room and asked my younger sisters to leave. “I think you’re old enough to hear this, Gay,” he said. He puffed himself up like a toad as he put on the mantel of patriarchy and laid down the law to my mom: “You cannot divorce Jack.”

My ultra-Catholic grandmother, a regular at daily mass, was so distraught by the idea of her son getting a divorce that she was unable to get out of bed. My grandfather shook his finger at my mother and scolded, “She even missed her bridge game.”

He said he knew about my dad’s girlfriend, and wandered into some claptrap about wild oats, men’s little peccadilloes, chickens coming home to roost, that left my mother looking as bewildered as I felt. He urged her to be patient, patted both our knees, and sat back, satisfied with his work. My mother said, “So you know Donna’s having Jack’s baby?” My grandfather did not know, and rendered speechless, he picked up his homburg and rushed out of the house.

My grandfather’s weird tirade, my parents’ divorce, the looming baby: I wrote all this off as proof of the insanity of the adult world. They were the straights, the squares, responsible for Vietnam, racism, and everything bad. The future was Woodstock, the Age of Aquarius, Haight-Ashbury, the Fillmore East, tune in, turn on, drop out. To hell with them. I had my own world of sex, drugs, friends, and school.

As befogged with love and LSD as my brain would be on Saturday nights with Michael, by Monday I was again the sharp-eyed, clear-headed, serious scholar. I couldn’t smoke a cigarette, I was a terrible dancer and a middling skier, but I could ace a test and write an essay that always came back with a bright red A+ scrawled on the top.

My favorite teacher, everyone’s favorite teacher, was Mr. Burrows, a Hollywood-ready character who had somehow, up in the Northern woods of Duluth, acquired not just an English accent, but a whole British persona. He had the proper squire’s paunch, not quite hidden by his baggy tweed suit. He lectured without notes, hundreds of years of history and literature nestled inside his head, as he almost danced about on his tiny feet, scribbling dates and names on the blackboard.

We smart kids were handed over to Mr. Burrows as sophomores, where we started with the Sumerians. We lucky few memorized many, many facts — ask any former student of Mr. Burrows when Menes united the Upper and Lower Kingdoms of Egypt and we will automatically spit out: “3400 B.C.” We learned big chunks of the Iliad and the Canterbury Tales by heart, and wrote many, many papers: on the Fertile Crescent, the birth of democracy in Greece, the fall of Rome. In his deep plummy voice, Mr. Burrows acted out his favorite scenes from history, which in his mind ended in 1900.

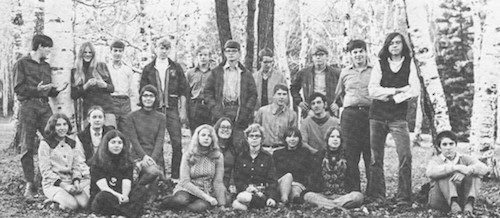

As juniors we spent two hours each day with Mr. Burrows, as he insisted that American history and American literature must be taught together. Nancy Erman and I sat with three other girls, surrounded by boys, as it seemed to be an ironclad rule that the ratio of smart boys to girls was 5:1. Michael Vlasdic and Needle sat together at the back of the class; in front of them the quartet of smart jocks sprawled loose-limbed at their desks, in all their nonchalant square-jawed handsomeness; awkward nerds in checked shirts and too-short pants made up the rest of the class.

Along with hours of reading a night, thrice weekly papers, and monthly quizzes leading up to a two day final, Mr. Burrows demanded that we retype the works of American authors from Jonathan Edwards’ sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” to Emily Dickinson’s poems (“I heard a fly buzz when I died,” “There is no frigate like a book,” “A bird came down the walk” — all nice and short), ending with Mark Twain and a chapter from A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Mr. Burrows believed that retyping all this deathless prose would help us grasp each writer’s style and salient points. By the end of the year, I had an eight-inch pile of paper, American Literature’s Great Hits, interspersed with my essays, all marked with that red A. I took all those typed pages to a print shop where they were bound in fake leather into a pair of two hundred-page books, my name gilded along the spine.

I adored Mr. Burrows even though he was the squarest of the square, the epitome of the conservative old fogey. A devout Christian, he even sang in the Congregationalist church choir, probably the only basso in the bunch. He was untouched by time. The tumultuous arrival of the ‘60s in Duluth did not faze him a bit. He had thirty years of teaching behind him, and behind that, three thousand years of history, which had taught him that this, too, shall pass. He ignored the “Make Love not War” and peace sign buttons Needle, Michael, and I wore, and the five girls wearing minis that barely covered their asses did not perturb him the least. (A decade later, I realized that Mr. Burrows had been the world’s most closeted homosexual.) What offended him was ignorance, stupidity, and ugliness, which was pretty much the entire twentieth century.

When as seniors we finally moved into Modern History, as required by the Duluth School Board, Mr. Burrows’ lectures became less spellbinding; unlike the Crusades or the American Revolution, the horrors of World Wars I and II were still too close to be romanticized. It may have been that Mr. Burrows didn’t care for the subject, or it may have been a brilliant teaching tactic: he actually passed a lot of the instruction over to us. Each student took turns researching a topic in current or recent affairs and presenting to the class. Youth in revolt, I chose the most leftist subjects I could find: the Cuban revolution, the rise of Ho Chi Minh, the election of Salvador Allende. While I spouted my idiotic admiration for these Reds, Mr. Burrows, the most hidebound of Tories, silently sat and stroked his ponderous lower lip.

Mr. Burrows was also the editor of The Open Mind, our high school’s “literary” magazine, filled with the pretentious and god-awful poetry and prose of disaffected, snotty teenagers like me. Supposedly all students at East could submit their work; in reality we never published anything by anyone who was not one of the elites in Mr. Burrows’ class.

The staff of The Open Mind met over tea and cookies at Mr. Burrows’ home, a two-story brick nearly as big as my family’s, which he had inherited from his parents (those were the days). His huge, old-fashioned living room, with scratchy horsehair furniture and ottomans, was clean and neat as a pin except for the books. The walls were lined with floor to ceiling bookcases, yet stacks of books covered every flat surface. We had to remove books from chairs before sitting, and re-pile books on other tables or the floor to make room for Mr. Burrows’ sterling silver tea service. We would pass around the pages that had been submitted that week to The Open Mind drop-box outside Mr. Burrow’s room and pass judgment. The bravest of us read their poems aloud, which we listeners inwardly despised and outwardly praised. Mr. Burrows used these meetings as an opportunity to further mold our impressionable young minds by playing his favorite opera records.

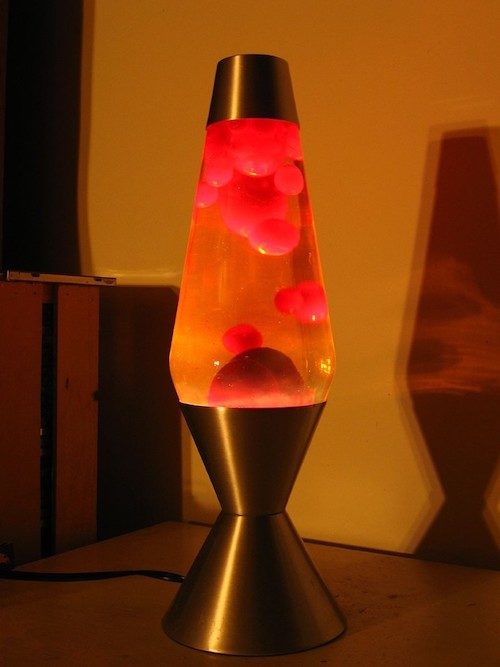

The Metropolitan Opera had long since crossed hick Duluth off its touring company’s itinerary, so once a year Mr. Burrows organized bus trips to Minneapolis to expose his lemming-like pupils to high culture. On Saturday, the Met performed two different operas. We made the three-hour road trip to Minneapolis, arriving at the immense Northrop Auditorium on the U of M campus in time for the matinee. As soon as the curtain rang down, Michael and I dashed over to the wonders of the Electric Fetus record store and head shop. Hookahs and chillums! Lava lamps! Books by Aldous Huxley and Carlos Castaneda! Black light posters! Michael bought strawberry flavored rolling papers and we went to eat.

Between operas I finally achieved my dream date of dinner at a real restaurant, sitting across from Michael at a white clothed table, wearing a pretty, opera-appropriate dress, even if I did have to pick up the tab for both of us. It was a quick date; we had less than an hour to enjoy our meal at Murray’s The Home of the Silver Butter Knife Steak before running back to Northrup for the evening performance. After the tragic death of Tosca or Mimi or Carmen we piled back in the bus and fell sound asleep, waking at three in the morning in the parking lot of East High, groggy and stiff from spending six hours in a bus seat and a day and night at the opera.

North Country Girl: Chapter 28 — The Age of Aquarius Comes to Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I didn’t tell Doug Figge about Wendi Carlson’s advice, that the key to enjoying sex is more sex. I didn’t have to. His mind was on the same track, the only track 17-year old boys’ run on, the track with the thundering locomotive of sex hurtling along, blowing all other thoughts away.

The day after the first man landed on the moon and I gave up my virginity, Doug called with the woeful news that Joe Sloan had emerged from his basement with powder burns and a singed shirt, accompanied by a powerful stink of cordite. His parents decreed that their house, including those forgotten bedrooms, was off limits.

Doug knew it was one of my mother’s class days. “Please, please,” he begged. “Let me come over. It will be okay, we’ll be quick,” he said as if that were a selling point. “Fine,” I sighed.

One of the things I learned from my first experience was that sex was messy, and should not take place on my mother’s ivory brocade French Provincial couch. Doug pulled into my driveway, I let him in the backdoor, and hurriedly escorted up him to my bedroom.

It was the middle of the afternoon and the sun streamed through my windows. I was shy about taking off my clothes in the summer glare, and not especially looking forward to seeing my fairly unattractive boyfriend naked either. I turned my back, stripped and slipped between the sheets, and there was Doug, nude and on top of me and ready.

I thought we were safe. My mother usually wasn’t home till three. But some vagary of the University of Minnesota’s college calendar or maybe the excitement of the moon landing had caused my mother’s class to be canceled that day. I heard a familiar car pull up to the house and thought “This is bad this is bad this is bad,” and tried to shove Doug off me. His eyes were squeezed shut, beads of sweat popping out on his wispy moustache; he was oblivious. “Doug Doug Doug,” I whispered hoarsely, as I heard the house door open and not only my mother’s voice, but my sisters’ as well. I pushed him harder and finally got him off me and he realized that my mother was home.

As Doug’s Corvair was in the driveway, my mother knew we were in the house alone, which she had strictly forbidden fearing exactly what had come to pass. Before Doug and I had a chance to find even our underwear, my mother flung open my bedroom door and lost her mind. She didn’t know whom to hit first. She whacked Doug about the head a few times, as he tried to find his jeans, the hell with his briefs, then she turned on me, as wordless as a banshee, unable to articulate what she had seen with her own eyes: her fifteen-year-old daughter having sex. I burst into tears and Doug made his escape.

That event is burned into my memory with almost a physical pain. I can feel the warm air coming in through the windows, pushing the sheer white curtains into the room. I can hear the torrent of my mother’s shrieks, and my entire body burning and blushing and trying to vanish into thin air. Out of the corner of my eye, while trying to duck my mother’s roundhouses, I see a blur that is Doug, holding his shirt and shoes, rushing down the stairs and out of my life.

A sadder but wiser fairy had come to undo one of my wishes, a wish that had gone horribly wrong. I no longer had a boyfriend. My mother forbade me to see Doug Figge ever again.

When I told Wendi Carlson about that shameful, sordid experience, she burst into peals of laughter, which shocked me into learning an important lesson: if your good friend cracks up at your sad story, it’s not the tragedy you think it is.

Egged on by Wendi, I held my gang of girlfriends spellbound for the remaining weeks of summer with the gripping tale of my mother catching me in bed with Doug Figge. “Tell it again!” they’d squeal, as we sat by a bonfire or dangled our legs in the water off a lakeside dock. I’d get to the point where Doug tore bare butt down the staircase, and they’d roar, squirting beer through their noses. Every time I re-told that tale of horror, it became less real, more like something that happened to another person.

“You need a new boyfriend!” cried Nancy, Wendi, and all the other girls. I wasn’t sure that I did. My romantic history consisted of a single date with Wesley Baggot, being publicly dumped by Steve LaFlamme, a forced make out session with a candidate for a skin graft, and having a boyfriend for six months that I didn’t really like and who never took me out once on a real date.

If I was going to have another boyfriend, I was going to pick him out myself. No more waiting passively for some boy to choose me; I had enough of that during those nightmarish ballroom dance classes. From now on, every day was going to be Sadie Hawkins Day.

I rejected all the efforts my pals made to fix me up. I studied the eligible guys in the packs that hovered around us, looking in vain for potential boyfriend material, someone who was good-looking and smart and funny. My imaginary future boyfriend had to go to East High, so he could hold my hand in the halls and take me to a school dance. I was through with boys who went to weird other schools, unless Joe Sloan reappeared.

Maybe it was this gritty new determination, maybe it was getting rid of my virginity at fifteen-and-a-half: I grew a backbone. I found I could talk, and laugh, and flirt with boys, ignoring the voice in my head that told me I sounded like an idiot.

Now I needed to shed my gawky nerd look, my face hidden behind those oversized tortoise-shell spectacles with the Coke bottle lenses. My mother was still not talking to me, just shooting me looks that alternated between disappointment and disgust. I turned on my father at every occasion, begging for contact lenses. Dad preferred that I remained unattractive; he didn’t know that the worst had already happened. My eye doctor won the argument for me, pointing out to my father that contacts would slow down my eyes’ deterioration to Mr. Magoo-level near-sightedness, and eliminate the need to buy new and thicker glasses every year. I got my contacts and I promptly lost one in our gold shag carpet. So much for my dad saving money on my eye care; it was back to the doctor to order another $30 contact. Now both my parents were mad at me.

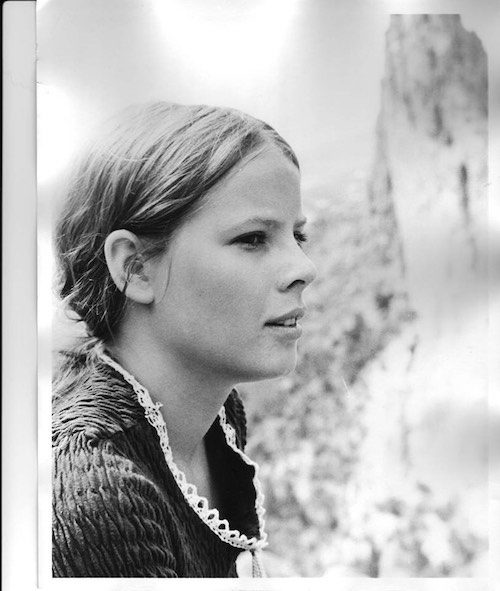

Who cared about parents when there was a potential boyfriend somewhere out there, a boyfriend who could now gaze directly into my green eyes, while stroking my hair. I hadn’t allowed a scissor to come near my head for months and my hair now flowed halfway down my back, an unremarkable brown, but thick and shiny with youth and health, perfect hippie girl hair. I also decided to stop letting my mother pick out my clothes. During our annual shopping trip to Minneapolis I ditched my mom and sisters in Dayton’s Back to School section and found an incense-smoky store where I bought a purple leather fringed jacket, a collection of gauzy Indian shirts, and embroidered bell bottom jeans. Suddenly instead of a four-eyed geek with a bad haircut, there was a cute girl in the mirror. My third wish, a wish so improbable and so desperate that I had never consciously acknowledged it, had been granted.

***

Late in August Walter Cronkite reported that thousands upon thousands of hippies had descended on a farm in upstate New York for a three-day music festival. The six o’clock news never showed any of the music, only the miles of traffic and abandoned cars and then finally half-naked people rolling about in the mud, Walter tut-tutting away like a maiden aunt. It looked amazing, the most fun a teenager could have. I watched desolate, knowing my tribe was out there, listening to the music I loved, taking the drugs I wanted. As always, life was happening somewhere else.

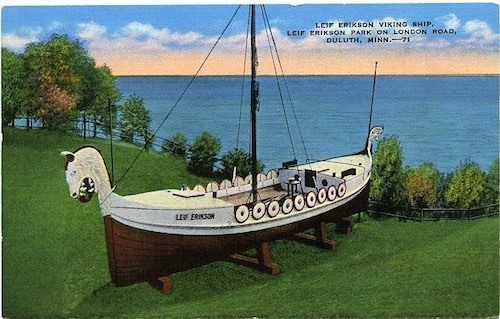

But Woodstock unlocked something in the teenagers of Duluth. As if summoned by the Pied Piper, throngs of kids coalesced in scraggy bands on the rolling green lawns of Leif Erickson Park, boys strumming guitars and girls twirling their long gypsy skirts around and around. At the downtown Woolworth’s next to the turtle tank I found a rack of buttons with peace symbols and “Make Love Not War” that I pinned on the lapel of my fringed jacket. The Age of Aquarius had reached Duluth.

On the first day of school, I walked down the East High hall into a different world. A whole subset of druggies and hippies had sprung up like dandelions. There were dozens of kids in tie-dye, patchouli oil was used way too liberally, and almost every boy, including the jocks, had hair that brushed the collars of their shirts.

I made my way up to the third floor, to Mr. Burrows’ two-hour, buttock-killing, smart-kids-only, enthralling American History and Literature Class, an educational jewel that was more fascinating and more informative than any college course, even if it did hew to the Famous White Men model, with nods to Anne Bradstreet and Emily Dickenson. As I slipped into my usual seat next to Nancy Erman, she nudged me, nodded her head sideways, and daringly whispered “New boy. Your type.” Mr. Burrows’ thundering brow turned toward Nancy at this violation of his rule of absolute silence. She gave him a twinkling Nancy smile, and, mollified, Mr. Burrows went back to the chalkboard to write: “A true relation of such occurrences and accidents as hath hapned in Virginia. John Smith, 1608,” and we were off to the races, three hundred years of history and literature to cover in nine months.

I snuck a glance in the direction Nancy had nodded in. Sitting all alone against the back wall, lit like a Renaissance angel under the slanting autumn light that poured in through the diamond-paned windows, was a boy with long dark hair that reached his shoulders and John Lennon wire-rimmed glasses. Beneath the glasses and the hair was a cherubic face, as round and sweet as an apple, a face that wore a serious, studious expression that reminded me to turn, reluctant and hopeful, back to my own interrupted note-taking on the founding of Jamestown.

This boy was Michael Vlasdic, my first love.

He was heart-meltingly handsome, and I knew that he had to be smart to be in Mr. Burrows’ advanced class. Two hours later, when Mr. Burrows allowed questions and comments, Michael sat silent, although I did see him occasionally smile, revealing adorable dimples that would be so much fun to kiss.

Michael Vlasdic was also in my lunch period, where I clocked him sitting at the back of the raucous East cafeteria with Roger Dennison, another rare new kid, who was good-looking in a blond, high-cheeked, Slavic way despite a nose like a jagged ski run, and with my old friend Eric Olson from elementary school. Eric was now known as Needle, not for his use of intravenous drugs but for his extreme skinniness. Roger and Needle both sported nicely shaggy hair, though not as long as Michael’s.

A year ago, I would not have been able to walk within ten feet of a boy I liked without my stomach flipping over and my tongue gluing itself to the roof of my mouth. But good luck and bad experiences had given me confidence. I had shed my virginity and my goofy glasses and I had Michael Vlasdic in my sights.

The new, sophisticated me plopped down uninvited among the three boys, making sure that I was next to Michael, and finally put my mother’s advice—“Just walk up to a boy, say hi and start talking”—to the test. I smiled, asked Roger where he was from (Colorado, his father worked for the Air Force and had been transferred to Duluth’s tiny base), talked to Needle, another smarty pants, about our classes, and finally turned to Michael and said “I like your glasses.”

I watched his face and my heart gave a small thump. I thought, I know this person, I have been this person, struck dumb at the prospect of talking to the opposite sex. It was as if I could read what was going through Michael’s mind: “What does that mean? Is she making fun of me? Or should I say thank you and then say I like your shirt?” I could tell he was weighing all his options as if one wrong word could open up the cafeteria floor and send him down to Hades, while the other kids laughed and pointed at him.

It was too painful. I jumped back in and carried the conversation single-handedly (look mom!) until the bell rang to send us off to class. That was also my signal to make my move. “So Michael,” I said, “What are you doing Saturday night?” All three boys exchanged shocked, mystified looks, but there was none of the horror that I used to see on the faces of the boy I asked to dance at Cotillion.

Michael quietly admitted that he had no plans for Saturday night and then looked as if he were waiting for a stinging, “Oh I’m going to a fun party” from me.

I took a breath and said, “Do you want to go out, go do something?” A beatific smile crossed Michael’s face, revealing those adorable dimples that I could have kissed right there and then. I took this as a yes. We scribbled phone numbers in each others’ notebooks and I left feeling that little squeeze of my heart and tingling between my legs that I got listening to Robert Plant moan “The Lemon Song” or re-reading the dog-eared pages in my copies of Lolita and Candy that I hid between the mattresses.