Considering History: Operation Paperclip and Nazis in America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

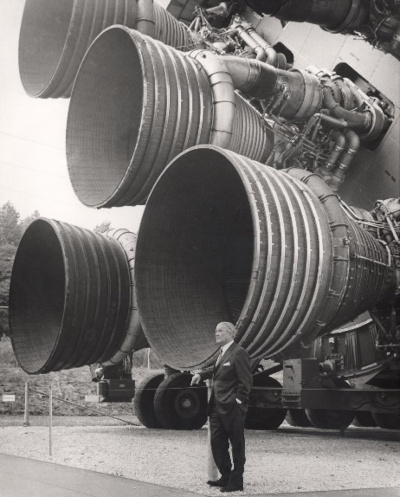

On September 20, 1945, the infamous Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun arrived at Fort Strong, a U.S. military site on Long Island in Boston Harbor. In a period when many of von Braun’s Nazi colleagues were preparing to be tried in the Nuremberg war crimes trials that would commence exactly two months later, von Braun and other Nazi scientists were instead being brought to the United States to serve as prized members (and often leaders) of teams researching the space program, weapons technology, and other initiatives. Known as Operation Paperclip, this secret endeavor, led by the federal government’s newly created Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), would eventually bring more than 1600 German scientists — many of them former Nazis — to America between 1945 and 1959.

The Soviet Union was similarly pursuing Nazi scientists for its own weapons and space programs, and so Operation Paperclip can be framed as part of the incipient Cold War, a reflection of how quickly and thoroughly the two nations pivoted from their tenuous World War II alliance to this new, multi-decade conflict. Yet at the same time, the relationship between the U.S. government and these Nazi scientists cannot be separated from the longstanding, deeply rooted presence of Nazis and antisemitism in America. From prominent figures and voices to mass movements and rallies, the two decades leading up to World War II featured numerous connections between Americans and Nazi Germany, links that reveal that Nazism was never simply a foreign or enemy force.

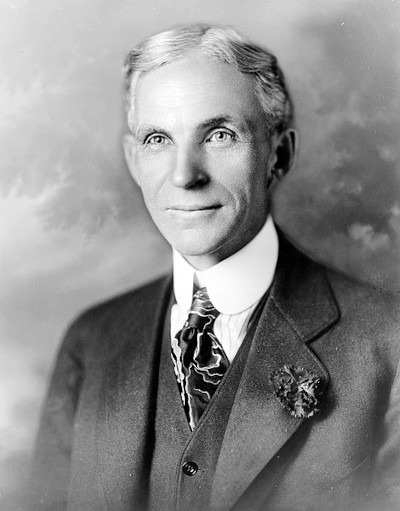

One of those Americans with close ties to Nazi Germany was also one of the most successful and famous Americans of the early 20th century: Henry Ford. The automobile inventor and entrepreneur wasn’t just a strident anti-Semite—he was apparently an influence on the rise of German Nazism and even Adolf Hitler himself. Between 1920 and 1927, Ford and his aide Ernest G. Liebold published The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper that they used principally to expound anti-Semitic views and conspiracy theories; many of Ford’s writings in that paper were published in Germany as a four-volume collection entitled The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem (1920-1922). Heinrich Himmler wrote in 1924 that Ford was “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters,” and Hitler went further: in Mein Kampf (1925) he called Ford “a single great man” who “maintains full independence” from America’s Jewish “masters”; and in a 1931 Detroit News interview, Hitler called Ford an “inspiration.” In 1938, Ford received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, one of Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honors.

After his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh was another of the period’s most famous Americans, and in 1938 Lindbergh likewise received a Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, this one from German air chief Hermann Goering himself. Over the next two years, Lindbergh’s public opposition to American conflict with Nazi Germany deepened, and despite subsequent attempts to recuperate that opposition as fear over Soviet Russia’s influence, Lindbergh’s views depended entirely on anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that equaled Ford’s. In a September 1939 nationwide radio address, for example, Lindbergh argued, “We must ask who owns and influences the newspaper, the news picture, and the radio station, … If our people know the truth, our country is not likely to enter the war.” Seen in this light, Lindbergh’s role as spokesman for the era’s America First Committee makes clear that that organization’s non-interventionist philosophies during World War II could not and cannot be separated from the antisemitism and Nazi sympathies of figures like Lindbergh and Ford.

American Nazism was much more than just a perspective held by elite anti-Semites — it was very much a movement. And like so many problematic social movements, it featured a demagogic voice to help spread its alternative realities — in this case, the Catholic priest turned radio host Charles Edward Coughlin. By the time World War II began, Coughlin had been publicly supporting both Nazi Germany and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for years; his weekly magazine, Social Justice, ran for much of 1938 excerpts from the deeply anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a text that contributed directly to Hitler’s views and the Holocaust. Both Social Justice and Coughlin’s radio show were hugely popular throughout the 1930s — a separate post office was constructed in his hometown of Royal Oak, Michigan just to process the roughly 80,000 letters he and show received each week—illustrating that American Nazism and anti-Semitism were widespread views in the period.

No moment reflected that American movement better than the February 20, 1939 rally that brought more than 20,000 Nazi supporters to New York’s Madison Square Garden. The rally was put on by the German American Bund, a national organization which consistently sought to wed pro-Nazi Germany sentiments to direct appeals to mythic images of American identity and patriotism. To that end, the rally was held on George Washington’s birthday, and the stage featured a portrait of Washington flanked by both American flags and Nazi flags/swastikas. After the rally opened with a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Bund secretary James Wheeler-Hill proclaimed in his introductory speech that “If George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler.” And in his closing speech, Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn went further, arguing that “The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of white gentile stock, and an American citizen imbued with patriotic zeal.”

Yet many other Americans expressed their patriotic zeal by opposing this Nazi rally. An estimated 100,000 protesters gathered outside the Garden, dwarfing the 20,000 or so Nazi sympathizers inside. The protesters featured World War I veterans, members of the Socialist Workers Party, and countless other local and national organizations and communities. And inside the rally, one young man took such opposition a step further: Kuhn’s speech was interrupted when Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old Jewish-American plumber’s assistant from Brooklyn (and future World War II naval sailor), charged the stage. Greenbaum was attacked by Bund guards, pulled away by police, and charged with disorderly conduct, for which he paid a $25 fine to avoid a 10-day jail sentence. But he was not the least bit apologetic, later stating, “Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing Hitler’s behind while thousands cheered? Well, I did it.”

Greenbaum and his fellow protesters make clear that these pro-Nazi sentiments were in no way unopposed in, nor exemplary of, 1930s America. But neither can those figures mitigate the troubling realities of the rally and its reflection of widespread American support for Hitler and the Nazis, support that included some of the nation’s most famous individuals as well as tens of thousands of other Americans. In a moment when Nazi imagery and sentiments have returned to American social and political debates, we would do well to remember their deep roots in our culture.

Featured image: German American Bund parade in New York City in 1937 (Library of Congress)

From Apollo to Artemis: 50 Years of NASA Construction in One Building

In 1964, NASA ordered the construction of a vast structure capable of assembling space vehicles to send to the moon. Over five decades later, that same building is gearing up to send them to Mars.

NASA publicly displayed their Moon to Mars initiative in May with the tagline “We Are Going.” To achieve the goal of reaching Mars, the first step is building infrastructure on the surface of the moon.

Sending humans back to the moon to build a sustainable launching point for Mars led NASA to develop the Space Launch System (SLS), a rocket capable of evolving over time to launch more than six missions of cargo and astronauts; the maiden voyage will blast-off in the summer of 2020.

NASA’s “We Are Going” video

50 years ago, the Apollo 11 mission landed the first humans on the moon, and today, the same facility where Apollo was built is being used to craft modern machinery to reach the next step with Artemis 1 — named after the goddess of the Moon and twin sister of the mythological god Apollo.

The two missions share more than just name, however; both are pioneering a new age of spacecraft construction. The NASA Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) — located at the Kennedy Space Center in Brevard, Florida — was constructed in 1966 to assemble the Saturn V rocket that carried the Apollo 11 mission crew. The VAB is one of the world’s largest buildings by volume, taking up 36,878 cubic miles of hangar space.

The massive structure closed down in 2014 for remodeling to prepare for the construction of the Orion rocket, the first piece of Artemis 1, and the SLS. The VAB is the birthplace of components for all NASA missions, including rockets, space shuttles, and satellites. Although the building was constructed in the ’60s, continual updates have made it a marvel of modern technology.

Before the 2014 remodel, rockets were built from platforms that surround the construction bays. As of the most recent update, the building has modular platforms in place that can move up, down, and around the rockets, meaning the necessary machinery can get in closer, be more precise, and take less time to assemble the pieces of the SLS.

On June 3, NASA reported that their workers at the VAB reached a critical checkpoint in the development of the first piece of the SLS. The first segment of the rocket’s main core stage has been nearly completed. The 190 feet tall core rocket stage is the first of six that will provide the thrust necessary to launch Orion to the moon. It is the largest rocket stage constructed since Saturn V.

The main core stage, as well as four supplementary boosters, will produce over 8.8 million pounds of thrust to propel the astronauts out of the Earth’s exosphere. By comparison, the Saturn V rocket required only 7.7 million pounds of thrust. The large scale improvement in rocket systems will allow Orion to reach the moon faster and with more cargo.

Through the 465-foot-high doors of the VAB come some of the world’s most advanced pieces of technology, but the building itself is certainly a unique piece of American industry. The building’s initial construction workers “grew up in work clothes and graduated in modern math and computerized controls,” as NASA put it in a promotional video. Building the VAB supplied jobs for more than 2,000 Americans in the construction, engineering, and steel industries.

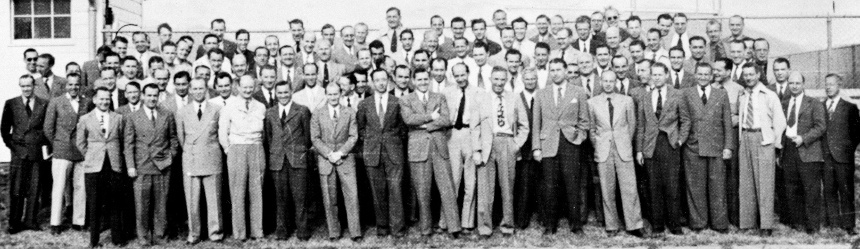

The VAB’s large stature is necessary to accommodate projects that are big enough to overcome the challenge of space travel, but with that much volume comes unforeseen consequences. The air conditioning system in the VAB is state of the art, not to cool the workers or the rocket, but to regulate the atmospheric conditions in the hangar. The ceilings of the hangar are so tall that, if left unchecked, clouds would form underneath them and, in the right conditions, bring down rain upon the spacecraft. Workers from the VAB

The physical size of the massive building is miniscule compared to the importance of the monumental missions that its products complete. The Artemis missions, SLS, and Orion are the key pieces to 2020’s space travel, both for the United States and for the world. In a statement about “Explore Moon to Mars,” NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said, “President Donald Trump has asked NASA to accelerate our plans to return to the Moon and to land humans on the surface again by 2024. We will go with innovative new technologies and systems to explore more locations across the surface than was ever thought possible. This time, when we go to the Moon, we will stay. And then we will use what we learn on the Moon to take the next giant leap — sending astronauts to Mars.”

As the United States continues to lead the charge for space exploration with help from the leading powers of the globe, the heart of international space technology is located in the hangar of the VAB. As it was described by NASA at its construction, “space and time are related in this great new age, but construction and time have always been married.” The VAB was designed with the future of humanity in mind and it continues to live up to that expectation. At its grand opening, it had the task of building Saturn V, which was like planting an acorn for the programs that followed; today, as shown by the technological advancements made to accommodate the construction of Artemis and the SLS, mighty oaks have grown.

Featured image: The VAB (NASA)