Considering History: Operation Paperclip and Nazis in America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

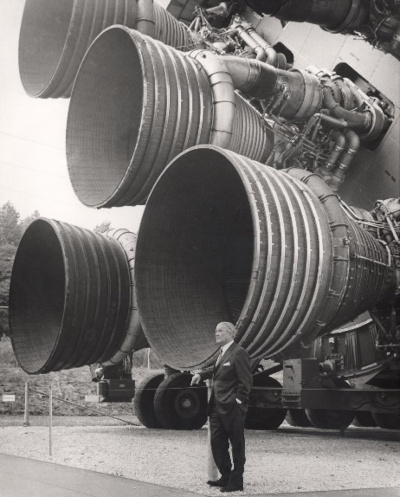

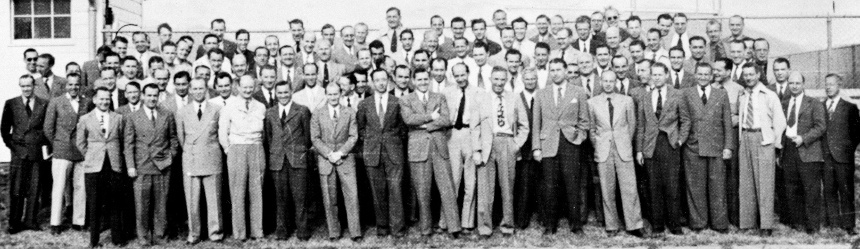

On September 20, 1945, the infamous Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun arrived at Fort Strong, a U.S. military site on Long Island in Boston Harbor. In a period when many of von Braun’s Nazi colleagues were preparing to be tried in the Nuremberg war crimes trials that would commence exactly two months later, von Braun and other Nazi scientists were instead being brought to the United States to serve as prized members (and often leaders) of teams researching the space program, weapons technology, and other initiatives. Known as Operation Paperclip, this secret endeavor, led by the federal government’s newly created Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), would eventually bring more than 1600 German scientists — many of them former Nazis — to America between 1945 and 1959.

The Soviet Union was similarly pursuing Nazi scientists for its own weapons and space programs, and so Operation Paperclip can be framed as part of the incipient Cold War, a reflection of how quickly and thoroughly the two nations pivoted from their tenuous World War II alliance to this new, multi-decade conflict. Yet at the same time, the relationship between the U.S. government and these Nazi scientists cannot be separated from the longstanding, deeply rooted presence of Nazis and antisemitism in America. From prominent figures and voices to mass movements and rallies, the two decades leading up to World War II featured numerous connections between Americans and Nazi Germany, links that reveal that Nazism was never simply a foreign or enemy force.

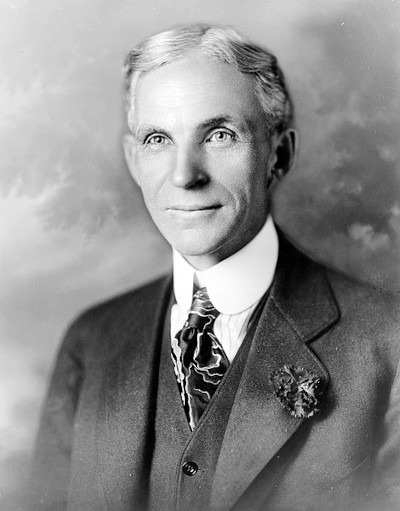

One of those Americans with close ties to Nazi Germany was also one of the most successful and famous Americans of the early 20th century: Henry Ford. The automobile inventor and entrepreneur wasn’t just a strident anti-Semite—he was apparently an influence on the rise of German Nazism and even Adolf Hitler himself. Between 1920 and 1927, Ford and his aide Ernest G. Liebold published The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper that they used principally to expound anti-Semitic views and conspiracy theories; many of Ford’s writings in that paper were published in Germany as a four-volume collection entitled The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem (1920-1922). Heinrich Himmler wrote in 1924 that Ford was “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters,” and Hitler went further: in Mein Kampf (1925) he called Ford “a single great man” who “maintains full independence” from America’s Jewish “masters”; and in a 1931 Detroit News interview, Hitler called Ford an “inspiration.” In 1938, Ford received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, one of Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honors.

After his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh was another of the period’s most famous Americans, and in 1938 Lindbergh likewise received a Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, this one from German air chief Hermann Goering himself. Over the next two years, Lindbergh’s public opposition to American conflict with Nazi Germany deepened, and despite subsequent attempts to recuperate that opposition as fear over Soviet Russia’s influence, Lindbergh’s views depended entirely on anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that equaled Ford’s. In a September 1939 nationwide radio address, for example, Lindbergh argued, “We must ask who owns and influences the newspaper, the news picture, and the radio station, … If our people know the truth, our country is not likely to enter the war.” Seen in this light, Lindbergh’s role as spokesman for the era’s America First Committee makes clear that that organization’s non-interventionist philosophies during World War II could not and cannot be separated from the antisemitism and Nazi sympathies of figures like Lindbergh and Ford.

American Nazism was much more than just a perspective held by elite anti-Semites — it was very much a movement. And like so many problematic social movements, it featured a demagogic voice to help spread its alternative realities — in this case, the Catholic priest turned radio host Charles Edward Coughlin. By the time World War II began, Coughlin had been publicly supporting both Nazi Germany and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for years; his weekly magazine, Social Justice, ran for much of 1938 excerpts from the deeply anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a text that contributed directly to Hitler’s views and the Holocaust. Both Social Justice and Coughlin’s radio show were hugely popular throughout the 1930s — a separate post office was constructed in his hometown of Royal Oak, Michigan just to process the roughly 80,000 letters he and show received each week—illustrating that American Nazism and anti-Semitism were widespread views in the period.

No moment reflected that American movement better than the February 20, 1939 rally that brought more than 20,000 Nazi supporters to New York’s Madison Square Garden. The rally was put on by the German American Bund, a national organization which consistently sought to wed pro-Nazi Germany sentiments to direct appeals to mythic images of American identity and patriotism. To that end, the rally was held on George Washington’s birthday, and the stage featured a portrait of Washington flanked by both American flags and Nazi flags/swastikas. After the rally opened with a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Bund secretary James Wheeler-Hill proclaimed in his introductory speech that “If George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler.” And in his closing speech, Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn went further, arguing that “The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of white gentile stock, and an American citizen imbued with patriotic zeal.”

Yet many other Americans expressed their patriotic zeal by opposing this Nazi rally. An estimated 100,000 protesters gathered outside the Garden, dwarfing the 20,000 or so Nazi sympathizers inside. The protesters featured World War I veterans, members of the Socialist Workers Party, and countless other local and national organizations and communities. And inside the rally, one young man took such opposition a step further: Kuhn’s speech was interrupted when Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old Jewish-American plumber’s assistant from Brooklyn (and future World War II naval sailor), charged the stage. Greenbaum was attacked by Bund guards, pulled away by police, and charged with disorderly conduct, for which he paid a $25 fine to avoid a 10-day jail sentence. But he was not the least bit apologetic, later stating, “Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing Hitler’s behind while thousands cheered? Well, I did it.”

Greenbaum and his fellow protesters make clear that these pro-Nazi sentiments were in no way unopposed in, nor exemplary of, 1930s America. But neither can those figures mitigate the troubling realities of the rally and its reflection of widespread American support for Hitler and the Nazis, support that included some of the nation’s most famous individuals as well as tens of thousands of other Americans. In a moment when Nazi imagery and sentiments have returned to American social and political debates, we would do well to remember their deep roots in our culture.

Featured image: German American Bund parade in New York City in 1937 (Library of Congress)

The True Story of Kelly’s Heroes

When Kelly’s Heroes hit theatres 50 years ago this week, it came amid a run of incredible success for its star, Clint Eastwood. While the film was not his biggest that year (that would be Two Mules for Sister Sara), it earned mostly positive reviews, recouped its budget, produced a Top 40 hit with the song “Burning Bridges,” and went on enjoy cult status and a place on many lists of the best war films. Most of the negative reviews focused on the uneasy balance between violence and comedy, but Arthur D. Murphy’s dismissal of the film as “preposterous” in Variety is ironic in hindsight. It certainly might seem that the idea of American soldiers in World War II teaming up with German locals to steal gold behind enemy lines is a flight of fancy; the shocking thing is that part is absolutely true.

The trailer for Kelly’s Heroes. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Kelly’s Heroes drew attention from the outset for the obvious reasons, like its cast. Eastwood’s star had been rising steadily for years, coming off of the Sergio Leone “Man with No Name” trilogy, WWII drama Where Eagles Dare, and other Westerns, while the following year would bring him The Beguiled, Play Misty for Me, and his most famous character in Dirty Harry. Kelly’s Heroes co-stars Telly Savalas and Donald Sutherland had both been standouts in The Dirty Dozen; Sutherland had also made a war picture mark in M*A*S*H earlier in the year. Don Rickles was, well, Don Rickles, and Carroll O’Connor was a tireless and familiar character actor one year out from his iconic turn as Archie Bunker.

The plot of the film follows Private Kelly (Eastwood) who discovers the existence of a cache of German gold after capturing a Wehrmacht intelligence officer. He assembles a misfit crew (including Sutherland’s tank squad), and the group makes a sustained effort to find and capture the gold. After fighting their way through a German tank blockade, the soldiers end up making a deal with the last German tank crew to share the gold. The characters split nearly $900,000 apiece and go their separate ways before they’re caught. And yes, something very similar to that actually happened.

The movies theme, Burning Bridges by The Mike Curb Congregation, went Top 40. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Mike Curb Congregation – Topic / Universal Music Group)

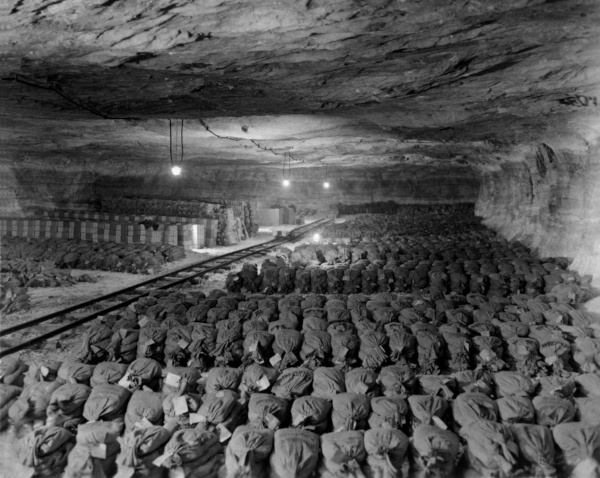

Writer Troy Kennedy Martin based the screenplay on an incident that he learned about from, of all places, The Guinness Book of World Records. “The Greatest Robbery on Record,” first listed in 1956 (and holding the spot until 2000), “was of the German National Gold Reserves in Bavaria by a combination of U.S. military personnel and German civilians in 1945.” MGM was so excited by the prospect that their head of production, Elliot Morgan, wrote Guinness for more information. Guinness’s understanding was that more details than that weren’t really available, possibly due to pieces of the story being classified. Martin used the entry as a starting point and wrote the screenplay.

However, the moviemakers weren’t the only intrigued parties. Ian Sayer is a British journalist, entrepreneur, and historian who has led an extremely colorful life. He founded a delivery service that helped pioneer overnight door-to-door delivery on the European continent. His work debunked fake Hitler diaries. And beginning in 1975, he started work on a book that would uncover the true story behind the gold heist.

Sayer’s book with Douglas Botting, Nazi Gold: The Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And Its Aftermath finally saw publication in 1984 (a second version, Nazi Gold: The Sensational Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And the Greatest Criminal Cover-Up, was published in 2012). The books detail that the U.S. Government covered up the theft of millions in Nazi gold from the German National Gold Reserve in Bavaria. The heist was executed by members of the U.S. military cooperating with former German officers, including one-time members of the Wehrmacht and SS. When Sayer sent his information to the U.S. State Department in 1978, it set the wheels turning for an investigation that began in the early 1980s. Eventually, the U.S. recovered two of the gold bars, identified by Nazi-stamped markings, and announced the finding in a press release in 1997. The two bars were valued at over $1 million and eventually found their way to the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold, the body that recovers and redistributes the gold that was seized by the Nazis during the war.

There’s one final twist. In 1984, Sayer spoke to Members of Parliament in an effort to get information about Nazi gold held by the Bank of England. Jeff Rooker, an MP who he had spoken to on the matter, asked Sayer in 1988 to check out an aid fund to ensure that the money was getting to the veterans it was supposed to serve. It turned out that that the citizen who had asked Rooker about the aid fund had been a survivor of the Wormhoudt massacre, when 90 unarmed British troops were killed by the SS in 1940. The officer responsible for the slaughter was SS General Wilhelm Mohnke, who had also guarded Hitler’s bunker and disappeared after World War II. Amazingly, Sayer realized that he’d met Mohnke while researching Nazi Gold without realizing the man’s identity; Sayer informed the authorities, leading to investigations into Mohnke from multiple countries. He was never charged due to insufficient evidence, and lived until 2000.

Today, Kelly’s Heroes is regarded as a classic war film, noted for its ensemble, its humor, and its willingness to show the dark moments of war even among a more lighthearted story. But the story of the film rests atop a much more complex true story, elements of which still remain hidden from view. It’s a good reminder that even as much as we think we know about history, there are always some secrets, and maybe some gold, hidden somewhere.

Featured image: Shutterstock