Saturday Evening Post Time Capsule: October 1938 – Aliens and Fascists

See all Time Capsule videos.

One of the illustrations by Henrique Alvim Corrêa for the original publication of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1906)(Public Domain Review)

Considering History: Operation Paperclip and Nazis in America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

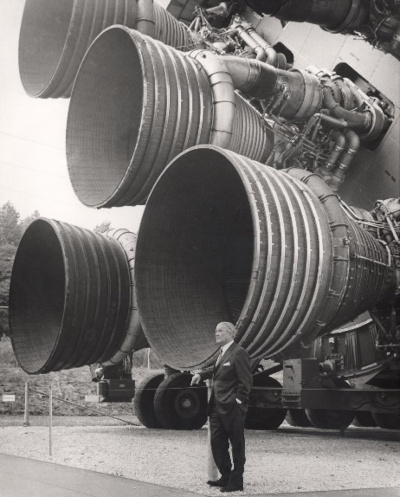

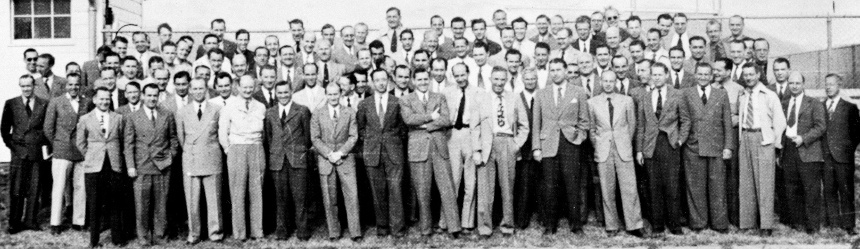

On September 20, 1945, the infamous Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun arrived at Fort Strong, a U.S. military site on Long Island in Boston Harbor. In a period when many of von Braun’s Nazi colleagues were preparing to be tried in the Nuremberg war crimes trials that would commence exactly two months later, von Braun and other Nazi scientists were instead being brought to the United States to serve as prized members (and often leaders) of teams researching the space program, weapons technology, and other initiatives. Known as Operation Paperclip, this secret endeavor, led by the federal government’s newly created Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), would eventually bring more than 1600 German scientists — many of them former Nazis — to America between 1945 and 1959.

The Soviet Union was similarly pursuing Nazi scientists for its own weapons and space programs, and so Operation Paperclip can be framed as part of the incipient Cold War, a reflection of how quickly and thoroughly the two nations pivoted from their tenuous World War II alliance to this new, multi-decade conflict. Yet at the same time, the relationship between the U.S. government and these Nazi scientists cannot be separated from the longstanding, deeply rooted presence of Nazis and antisemitism in America. From prominent figures and voices to mass movements and rallies, the two decades leading up to World War II featured numerous connections between Americans and Nazi Germany, links that reveal that Nazism was never simply a foreign or enemy force.

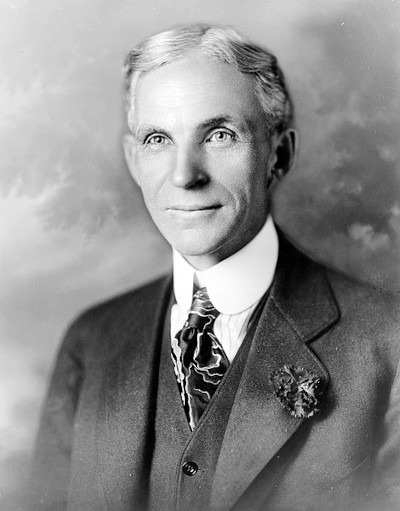

One of those Americans with close ties to Nazi Germany was also one of the most successful and famous Americans of the early 20th century: Henry Ford. The automobile inventor and entrepreneur wasn’t just a strident anti-Semite—he was apparently an influence on the rise of German Nazism and even Adolf Hitler himself. Between 1920 and 1927, Ford and his aide Ernest G. Liebold published The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper that they used principally to expound anti-Semitic views and conspiracy theories; many of Ford’s writings in that paper were published in Germany as a four-volume collection entitled The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem (1920-1922). Heinrich Himmler wrote in 1924 that Ford was “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters,” and Hitler went further: in Mein Kampf (1925) he called Ford “a single great man” who “maintains full independence” from America’s Jewish “masters”; and in a 1931 Detroit News interview, Hitler called Ford an “inspiration.” In 1938, Ford received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, one of Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honors.

After his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh was another of the period’s most famous Americans, and in 1938 Lindbergh likewise received a Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, this one from German air chief Hermann Goering himself. Over the next two years, Lindbergh’s public opposition to American conflict with Nazi Germany deepened, and despite subsequent attempts to recuperate that opposition as fear over Soviet Russia’s influence, Lindbergh’s views depended entirely on anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that equaled Ford’s. In a September 1939 nationwide radio address, for example, Lindbergh argued, “We must ask who owns and influences the newspaper, the news picture, and the radio station, … If our people know the truth, our country is not likely to enter the war.” Seen in this light, Lindbergh’s role as spokesman for the era’s America First Committee makes clear that that organization’s non-interventionist philosophies during World War II could not and cannot be separated from the antisemitism and Nazi sympathies of figures like Lindbergh and Ford.

American Nazism was much more than just a perspective held by elite anti-Semites — it was very much a movement. And like so many problematic social movements, it featured a demagogic voice to help spread its alternative realities — in this case, the Catholic priest turned radio host Charles Edward Coughlin. By the time World War II began, Coughlin had been publicly supporting both Nazi Germany and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for years; his weekly magazine, Social Justice, ran for much of 1938 excerpts from the deeply anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a text that contributed directly to Hitler’s views and the Holocaust. Both Social Justice and Coughlin’s radio show were hugely popular throughout the 1930s — a separate post office was constructed in his hometown of Royal Oak, Michigan just to process the roughly 80,000 letters he and show received each week—illustrating that American Nazism and anti-Semitism were widespread views in the period.

No moment reflected that American movement better than the February 20, 1939 rally that brought more than 20,000 Nazi supporters to New York’s Madison Square Garden. The rally was put on by the German American Bund, a national organization which consistently sought to wed pro-Nazi Germany sentiments to direct appeals to mythic images of American identity and patriotism. To that end, the rally was held on George Washington’s birthday, and the stage featured a portrait of Washington flanked by both American flags and Nazi flags/swastikas. After the rally opened with a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Bund secretary James Wheeler-Hill proclaimed in his introductory speech that “If George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler.” And in his closing speech, Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn went further, arguing that “The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of white gentile stock, and an American citizen imbued with patriotic zeal.”

Yet many other Americans expressed their patriotic zeal by opposing this Nazi rally. An estimated 100,000 protesters gathered outside the Garden, dwarfing the 20,000 or so Nazi sympathizers inside. The protesters featured World War I veterans, members of the Socialist Workers Party, and countless other local and national organizations and communities. And inside the rally, one young man took such opposition a step further: Kuhn’s speech was interrupted when Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old Jewish-American plumber’s assistant from Brooklyn (and future World War II naval sailor), charged the stage. Greenbaum was attacked by Bund guards, pulled away by police, and charged with disorderly conduct, for which he paid a $25 fine to avoid a 10-day jail sentence. But he was not the least bit apologetic, later stating, “Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing Hitler’s behind while thousands cheered? Well, I did it.”

Greenbaum and his fellow protesters make clear that these pro-Nazi sentiments were in no way unopposed in, nor exemplary of, 1930s America. But neither can those figures mitigate the troubling realities of the rally and its reflection of widespread American support for Hitler and the Nazis, support that included some of the nation’s most famous individuals as well as tens of thousands of other Americans. In a moment when Nazi imagery and sentiments have returned to American social and political debates, we would do well to remember their deep roots in our culture.

Featured image: German American Bund parade in New York City in 1937 (Library of Congress)

How the Allies Tried to Exorcise Nazism

Germany’s army may have surrendered on May 8, 1945, but Nazism never admitted defeat.

Though their nation was in ruins, millions of Germans still believed in Nazism. Nazi officials, however, found it expedient to profess their ignorance, resistance, and innocence of their government’s war crimes. Others denied their affiliation with the Nazis while remaining quietly committed to the policies of the now-dead Hitler.

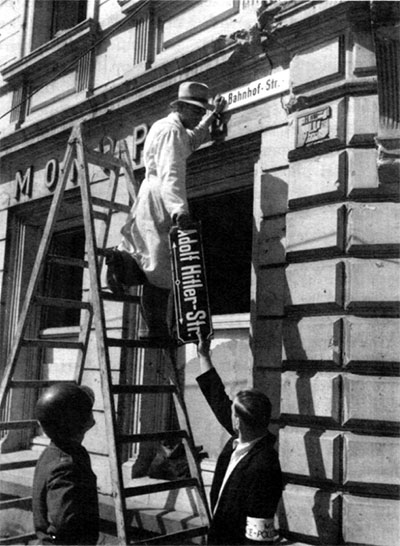

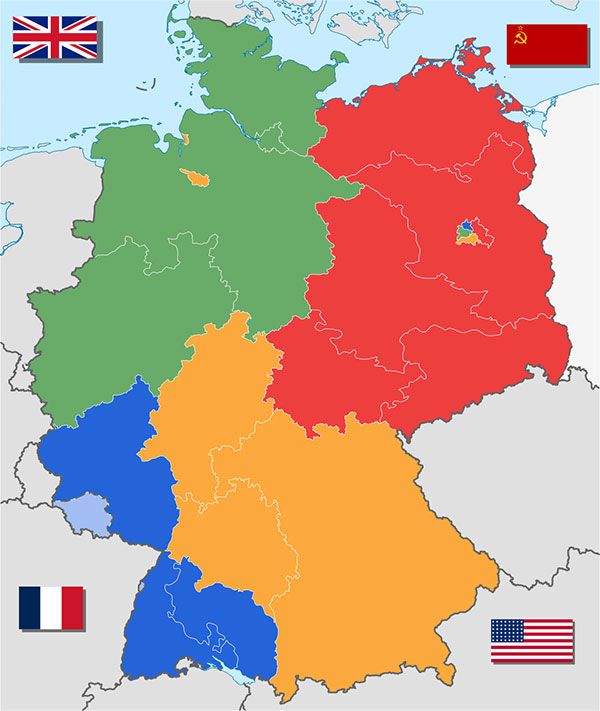

The Allies recognized the appeal of Nazism to a defeated people. The movement had sprung from Germany’s humiliating defeat 27 years earlier. To eradicate the idea, all four major powers — America, Russia, Britain, and France — agreed to a plan of denazification. They would hold the supporters of the Nazi government accountable for their crimes, eradicate Nazi regalia, and present the country with the scope of Nazi crime.

Under this plan, Germans who held government offices under the Nazis lost their jobs. The Nazi party was banned, and advocating its ideas was punishable by death. The swastika and other party symbols were removed from public view.

All Germans had to fill out a questionnaire about their involvement in Nazism.

Ex-Nazis and local residents were forced to walk through concentration camps, or made to watch movies of the abuse of Jewish prisoners.

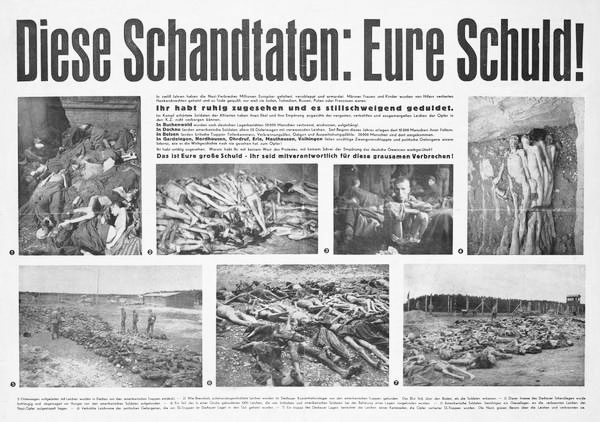

The German people were also told they bore responsibility. They were given booklets with photographs of concentration camp victims, bearing the words “You are guilty of this!”

The Allies each occupied a sector of the country and divided the task of investigating the 45 million Germans who worked for the Nazis. They included not just members of the army and secret police but also industrialists, arms dealers, and business owners who’d employed Nazi slave labor.

The original idea was to hold all Nazis accountable, but this proved impractical. There were simply too many to investigate. And the U.S. military was bringing 785 top Nazi scientists and engineers to America without any inquiry into their politics.

In the American sector of Germany, over 170,000 Germans could be held until their case could be heard by a tribunal of American officials. Following their hearing, they were assigned to one of four groups.

- Group I: Major offenders, who were subject to arrest, trial, and a possible sentence of death or long imprisonment. Their public trials, like those held in Nuremburg, were meant to discredit them, publicize their atrocities, and justify Allied justice to the German people.

- Group II: Offenders — activists, militants, and profiteers. They would be sentenced to imprisonment.

- Group III: Lesser Offenders who weren’t imprisoned but placed on probation, with restricted rights, for up to three years.

- Group IV: Followers, who were prohibited from holding public office, fined, and limited to performing manual labor. Young adults in this category were barred from university admission.

The remainder were classified as “Exonerated.”

The process was laborious and time consuming, and the American soldiers who worked on the tribunals wanted to go home. The Americans gradually handed the job over to the Germans.

Meanwhile, in the French sector, the screening for Nazis became more lax, and the British were soon loosening their standards for prosecution as well. Many war criminals in the American sector fled to the British zone and escaped punishment.

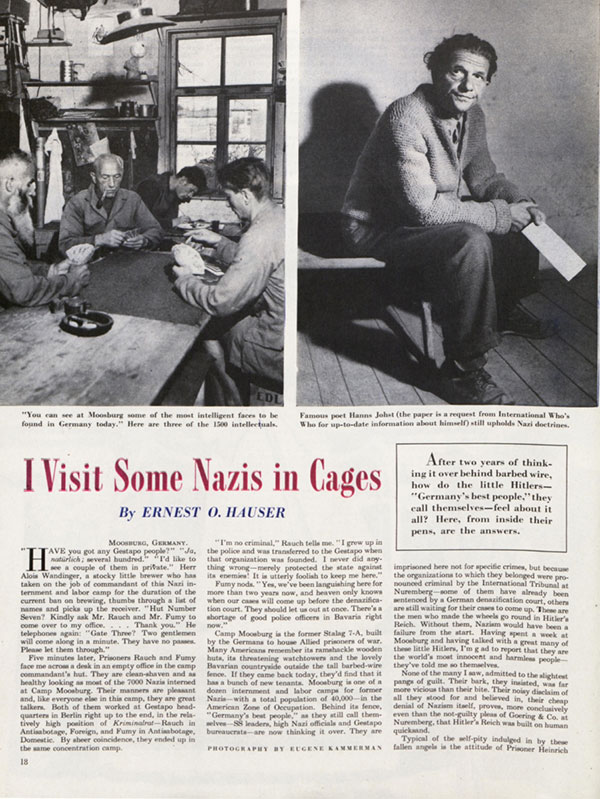

Thousands, though, were still held by U.S. authorities at the Moosburg Prison, formerly Stalag VI-A, Germany’s largest POW camp. Here army officers and high-ranking civilians awaited their hearings.

When Post journalist Ernest O. Hauser visited Moosburg in 1947, [“I Visit Some Nazis in Cages,” Oct. 11, 1947] his first request was to interview captured Gestapo officers. The two he met assured him they’d done nothing wrong. They’d been police men who were ordered into the Gestapo. Since then, they had “merely protected the state against her enemies.”

Hauser also interviewed Heinrich Hoffer, Hitler’s photographer and the man who introduced him to Eva Braun. Hoffer’s defense was he’d only joined the Nazi party because an American editor had offered him a thousand dollars to photograph Hitler, and he had to be a party member to get close to the Fuhrer.

After several more interviews with suspected Nazis, Hauser wrote, “I’m glad to report that they are the world’s most innocent and harmless people — they told me so themselves.”

Inmates who hoped to be classified as a Category III or IV had to provide evidence they were one of the “good” Nazis. The best approach, Hauser wrote, was to claim they had secretly helped Jews. “In hearing the prisoners talk about the kindly interest they always took in their Jewish compatriots,” he wrote, “one might easily think that the Nazi Party was a society for the care and protection of Judaism.”

Hauser noted the thousands of “intellectuals” in the camp — highly intelligent, well educated professionals who considered themselves, as did other Germans, as the best people in Germany. These academics and professionals were responsible for the highly efficient Nazi government. Now they demanded release, claiming to be the only hope against communism. “The Bolsheviks are coming!” they cried, according to Hauser “Let us out! We are the saviors of Europe.”

In truth, their expertise was sorely missed in a country where inexperienced civilians were trying to revive the country. Immediately after the fighting had stopped, the allies had dismissed nearly half of all Germany’s public officials.

American officers admitted to Hauser that war criminals were slipping through their hands. The guards were underpaid German civilians who, for as little as three packs of cigarettes, would look the other way as a prisoner slipped out.

When Germans took over the tribunals, they began speeding up the hearings. They released the younger detainees by declaring anyone born after 1919 (i.e., those who’d been adolescents when Hitler came to power) had been “brainwashed.” In later decisions, the German panels determined 90 percent of detainees didn’t require a trial. Even so, by 1947, over 90,000 Germans still remained in detention.

The results of denazification were not encouraging to American authorities. Much of the German population remained in sympathy with Hitler and his party, even after the public trials and the publicizing of the Holocaust. In 1946, 37 percent of Germans said the Holocaust was necessary for the security of Germans. In 1952, one fourth of Germans still had a good opinion of Hitler. General Eisenhower believed it would take 50 years for the spirit of Nazism to die.

At least 200,000 Germans participated in Nazi crimes. In a CNN article, German history professor Mary Fulbrook says that the tribunals heard 140,000 cases between 1945 and 2005, but just over 6,650 were convicted.

Eventually, 270 Nazis in were tried in court and found guilty. Death sentences were handed down for 190 (though 28 were commuted to lengthy prison terms). Few of the industrialists accused of profiting from slave labor faced severe punishment.

Of all the top Nazis, seven were sentenced to particularly long sentences in Berlin’s Spandau Prison. The last convicted Nazi was Rudolf Hess, who had been imprisoned since flying to England on a one-man peace mission in 1941. After 46 years in prison, he committed suicide in 1987, at the age of 93.

What of the rest? Those who couldn’t successfully lie about their Nazi past fled the country. In 2012, a British paper studied immigration papers from Brazil and Chile and concluded that 9,000 Nazis from Germany and neighboring countries had fled to South America after the war. Most resettled in Argentina.

The spirit of Nazism never fully died, as can be seen at protest rallies around the world today. But it lost much of its appeal when Germans saw a democratic government, supported by western allies, successfully oppose Russian aggression, and standing firm in West Berlin. They could see two futures, one of abundance with the West or austerity with the East, separated by only a wall. And a younger generation were better informed than they were in the Nazi era. According to one teacher in that 1945 Post article, German youth needed a better spirit of enlightenment and tolerance. As he told Hauser, “Democracy is not just majority rule — it is respect for the minority.

Featured image: Germans removing a street sign named after Adolf Hitler (Wikimedia Commons)