Germany’s army may have surrendered on May 8, 1945, but Nazism never admitted defeat.

Though their nation was in ruins, millions of Germans still believed in Nazism. Nazi officials, however, found it expedient to profess their ignorance, resistance, and innocence of their government’s war crimes. Others denied their affiliation with the Nazis while remaining quietly committed to the policies of the now-dead Hitler.

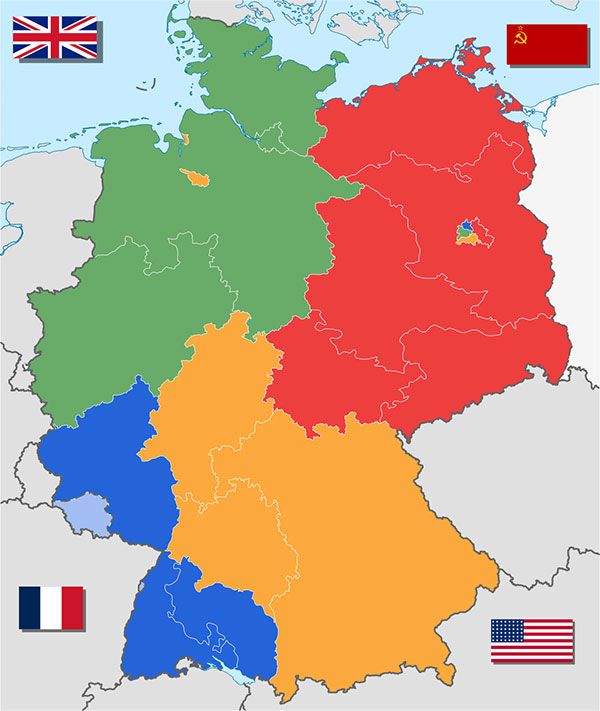

The Allies recognized the appeal of Nazism to a defeated people. The movement had sprung from Germany’s humiliating defeat 27 years earlier. To eradicate the idea, all four major powers — America, Russia, Britain, and France — agreed to a plan of denazification. They would hold the supporters of the Nazi government accountable for their crimes, eradicate Nazi regalia, and present the country with the scope of Nazi crime.

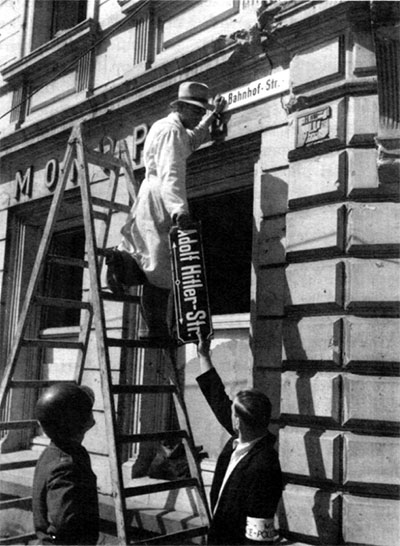

Under this plan, Germans who held government offices under the Nazis lost their jobs. The Nazi party was banned, and advocating its ideas was punishable by death. The swastika and other party symbols were removed from public view.

All Germans had to fill out a questionnaire about their involvement in Nazism.

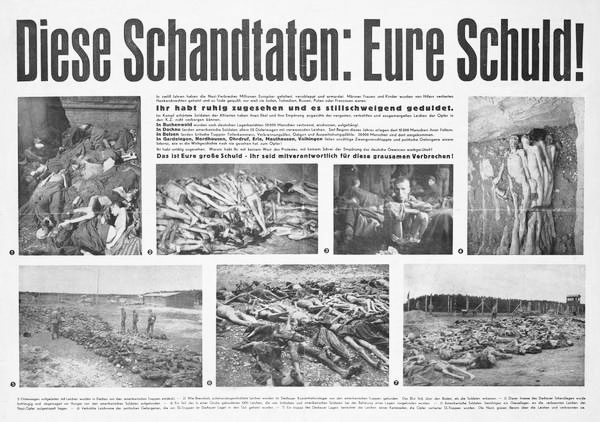

Ex-Nazis and local residents were forced to walk through concentration camps, or made to watch movies of the abuse of Jewish prisoners.

The German people were also told they bore responsibility. They were given booklets with photographs of concentration camp victims, bearing the words “You are guilty of this!”

The Allies each occupied a sector of the country and divided the task of investigating the 45 million Germans who worked for the Nazis. They included not just members of the army and secret police but also industrialists, arms dealers, and business owners who’d employed Nazi slave labor.

The original idea was to hold all Nazis accountable, but this proved impractical. There were simply too many to investigate. And the U.S. military was bringing 785 top Nazi scientists and engineers to America without any inquiry into their politics.

In the American sector of Germany, over 170,000 Germans could be held until their case could be heard by a tribunal of American officials. Following their hearing, they were assigned to one of four groups.

- Group I: Major offenders, who were subject to arrest, trial, and a possible sentence of death or long imprisonment. Their public trials, like those held in Nuremburg, were meant to discredit them, publicize their atrocities, and justify Allied justice to the German people.

- Group II: Offenders — activists, militants, and profiteers. They would be sentenced to imprisonment.

- Group III: Lesser Offenders who weren’t imprisoned but placed on probation, with restricted rights, for up to three years.

- Group IV: Followers, who were prohibited from holding public office, fined, and limited to performing manual labor. Young adults in this category were barred from university admission.

The remainder were classified as “Exonerated.”

The process was laborious and time consuming, and the American soldiers who worked on the tribunals wanted to go home. The Americans gradually handed the job over to the Germans.

Meanwhile, in the French sector, the screening for Nazis became more lax, and the British were soon loosening their standards for prosecution as well. Many war criminals in the American sector fled to the British zone and escaped punishment.

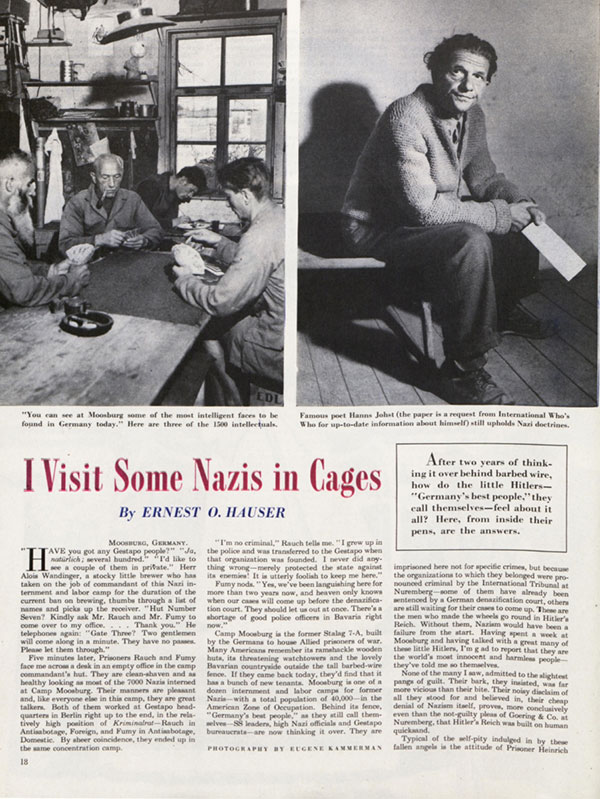

Thousands, though, were still held by U.S. authorities at the Moosburg Prison, formerly Stalag VI-A, Germany’s largest POW camp. Here army officers and high-ranking civilians awaited their hearings.

When Post journalist Ernest O. Hauser visited Moosburg in 1947, [“I Visit Some Nazis in Cages,” Oct. 11, 1947] his first request was to interview captured Gestapo officers. The two he met assured him they’d done nothing wrong. They’d been police men who were ordered into the Gestapo. Since then, they had “merely protected the state against her enemies.”

Hauser also interviewed Heinrich Hoffer, Hitler’s photographer and the man who introduced him to Eva Braun. Hoffer’s defense was he’d only joined the Nazi party because an American editor had offered him a thousand dollars to photograph Hitler, and he had to be a party member to get close to the Fuhrer.

After several more interviews with suspected Nazis, Hauser wrote, “I’m glad to report that they are the world’s most innocent and harmless people — they told me so themselves.”

Inmates who hoped to be classified as a Category III or IV had to provide evidence they were one of the “good” Nazis. The best approach, Hauser wrote, was to claim they had secretly helped Jews. “In hearing the prisoners talk about the kindly interest they always took in their Jewish compatriots,” he wrote, “one might easily think that the Nazi Party was a society for the care and protection of Judaism.”

Hauser noted the thousands of “intellectuals” in the camp — highly intelligent, well educated professionals who considered themselves, as did other Germans, as the best people in Germany. These academics and professionals were responsible for the highly efficient Nazi government. Now they demanded release, claiming to be the only hope against communism. “The Bolsheviks are coming!” they cried, according to Hauser “Let us out! We are the saviors of Europe.”

In truth, their expertise was sorely missed in a country where inexperienced civilians were trying to revive the country. Immediately after the fighting had stopped, the allies had dismissed nearly half of all Germany’s public officials.

American officers admitted to Hauser that war criminals were slipping through their hands. The guards were underpaid German civilians who, for as little as three packs of cigarettes, would look the other way as a prisoner slipped out.

When Germans took over the tribunals, they began speeding up the hearings. They released the younger detainees by declaring anyone born after 1919 (i.e., those who’d been adolescents when Hitler came to power) had been “brainwashed.” In later decisions, the German panels determined 90 percent of detainees didn’t require a trial. Even so, by 1947, over 90,000 Germans still remained in detention.

The results of denazification were not encouraging to American authorities. Much of the German population remained in sympathy with Hitler and his party, even after the public trials and the publicizing of the Holocaust. In 1946, 37 percent of Germans said the Holocaust was necessary for the security of Germans. In 1952, one fourth of Germans still had a good opinion of Hitler. General Eisenhower believed it would take 50 years for the spirit of Nazism to die.

At least 200,000 Germans participated in Nazi crimes. In a CNN article, German history professor Mary Fulbrook says that the tribunals heard 140,000 cases between 1945 and 2005, but just over 6,650 were convicted.

Eventually, 270 Nazis in were tried in court and found guilty. Death sentences were handed down for 190 (though 28 were commuted to lengthy prison terms). Few of the industrialists accused of profiting from slave labor faced severe punishment.

Of all the top Nazis, seven were sentenced to particularly long sentences in Berlin’s Spandau Prison. The last convicted Nazi was Rudolf Hess, who had been imprisoned since flying to England on a one-man peace mission in 1941. After 46 years in prison, he committed suicide in 1987, at the age of 93.

What of the rest? Those who couldn’t successfully lie about their Nazi past fled the country. In 2012, a British paper studied immigration papers from Brazil and Chile and concluded that 9,000 Nazis from Germany and neighboring countries had fled to South America after the war. Most resettled in Argentina.

The spirit of Nazism never fully died, as can be seen at protest rallies around the world today. But it lost much of its appeal when Germans saw a democratic government, supported by western allies, successfully oppose Russian aggression, and standing firm in West Berlin. They could see two futures, one of abundance with the West or austerity with the East, separated by only a wall. And a younger generation were better informed than they were in the Nazi era. According to one teacher in that 1945 Post article, German youth needed a better spirit of enlightenment and tolerance. As he told Hauser, “Democracy is not just majority rule — it is respect for the minority.

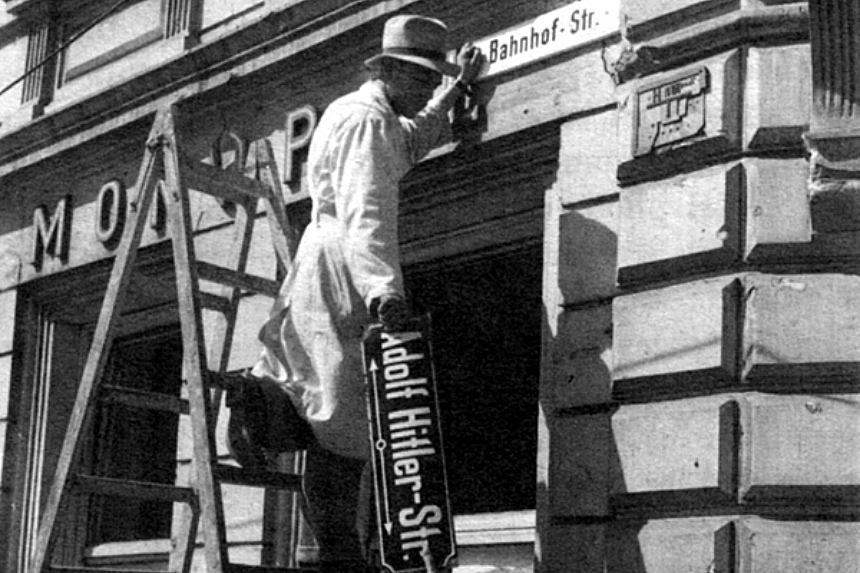

Featured image: Germans removing a street sign named after Adolf Hitler (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

British guilt over fire bombing and saturation raids of all german major cities that killed million children and non combatants in the last 6 months of the war likely. led to their quickly deciding to limit nazi prosecutions

But they were wring to fail to rigorously prosecute wring doing simply because questionable actions were repeatedly announced in the british. French. And usa press

If crimes are not prosecuted you inevitably get more crimes

Brainwashed or not

A 29vto 25 year old guard at concentration camp committed crimes against humanity

and needed to be punished to incentivise future young people to take stock of their actions

It would be interesting to know what percentage of those “pitiful brainwashed young adults ever

accepted moral if not legal responsibility for their actions

When people say it never happened it makes me mad ! I knew a lady who lived it and lost her whole family. God help us if this ever happens again due to ignorance !

All 300 000 members of the ss committed or assisted in commission of war crimes against civilians

Each should have been tried in the morning and executed in the same afternoon

Without the living head the snake of natz would gave died quickly

I claim this as a devout catholic not a jew

But I am also a realist

Nit surprising that 9000 escaped to Argentina. As the war was coming to a close of course a rat line was established to provide escape paid for by confiscated wealth

What surprises me is that the us. British. French or Russian government did not bribe or coerce Argentina officials into ejecting them so they could be captured and punished

Whatever bribes natz paid could certainly be eclipsed by much bigger bribes from a nation state

Failing in that. Then try them in absentia and send in rangers with skills honed in war to eliminate them

It would have been nearly universally viewed as just punishment

Allowing german courts to judge othet germans was a disgraceful abuse of justice

If the majority of the victims had been Christians in stead if Jews more effective punishment of the guilty would have occurred

It is interesting to note that Germans who were born after 1919 were considered “brainwashed“ and not held liable for the atrocities performed by the Nazis. Given the distinctions and variations noted in the immediate post-war period between those who were responsible for forming policy and those who carried it out (whether willingly or under duress or even under delusion) it is a wonder why, 60 to 75 years later, that people — then, young men — who did nothing more than be assigned as guards at a concentration camp are now deemed to be the ones who were criminally responsible.

What happened to the Nazi Party and its followers in ’45-’47 is something I don’t think most Americans at the time probably thought about, which was understandable after 16 very tough years (1929-’45). This is why the Allied occupation zones in post-war Germany were so crucial to bring as many to justice as possible.

This Party was not just going to “go away” at all. The collaboration of the US., France, England and Russia was a good idea, and the four categories of severity. Too many of them still got away with their crimes; fleeing to Argentina and more. This doesn’t mean the attempts to shut the Nazi Party down was a failure, even though it wasn’t the success they’d envisioned either. It needs to be viewed that the Nazi Party was successfully weakened in the mid-late ’40s as to not have the power for a Hitler regime resurgence, as it has not (again) for 75 years.

It must continue to be kept under continual surveillance so any attempt at a comeback can be stopped in its tracks. This likely has happened many times since then, that we (the public) weren’t aware of. Unforunately, it’s something just under the surface that will always require close watching.