News of the Week: Killer Bees, Four Freedoms, and People Try to Name a Book (Any Book at All)

The Sting of Spring

Mother Nature and assorted meteorologists have been toying with us this spring, throwing in 49-degree days along with the 70-degree ones. But we’ve turned a corner. The warm weather is here. There’s no turning back now.

I killed a giant bee in my apartment recently. The first appearance of an insect in the spring is always a bit disorienting. I heard the buzzing sound, but it was so loud I thought it was coming from construction equipment down the street. Then I saw it fly by my television and flap around the window. At first I didn’t know what to attack it with. A shoe would have been cumbersome in the window, and I didn’t want to use my copy of The Saturday Evening Post. So I used the next most logical thing: the 1951 Loretta Young film noir Cause for Alarm! Hey, I panicked and didn’t want the bee to get away! For some reason I own two copies of it and decided to sacrifice one to squash the bee (in my defense, it is considered a B-movie).

I’m usually a curmudgeon when it comes to warm weather. I start complaining about the temperatures on Memorial Day and I don’t stop until after Labor Day. But this year, I’ve decided to embrace it. I’ll wear shorts and drink cold drinks and watch tennis until the better weather comes along. If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. Just make sure you have plenty of extra DVDs on hand to kill the bugs.

Want, Worship, Speech, Fear

Starting today, the New York Historical Society will host an exhibition of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, in a celebration of Rockwell, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and America. The “Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms” exhibition will last until September 2 and will then go on tour to several other locations around the world, including The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C., the Mémorial de Caen in Normandy, France, and the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

To celebrate the tour, Turner Classic Movies had a marathon of movies inspired by Four Freedoms this week, hosted by Ben Mankiewicz. It included an interview with Harvey J. Kaye, author of The Fight for the Four Freedoms: What Made FDR and the Greatest Generation Truly Great. The films Mankiewicz and Kaye discussed included The Grapes of Wrath, Casablanca, Deadline U.S.A., and two short films from 1945: The Cummington Story and The House I Live In, with Frank Sinatra.

Guitar Hero

A guitar that Bob Dylan played on his first electric tour — and later strummed by Robbie Robertson — sold at auction this week for $490,000.

It should be noted, however, that this isn’t the guitar Dylan played at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, the one that caused an uproar because some fans just couldn’t believe he had gone electric. That concert is one of the many topics in this 1968 Post profile of Dylan by Alfred Aronowitz.

Shirley

I love going through the Post archives to see who wrote for the magazine over the years. It’s an impressive list, and it includes Shirley Jackson, probably best known for her short story that’s taught in every high school English class, “The Lottery.” In the March 27, 1965, issue we published Jackson’s short story “The Bus.” She died just five months later.

This week it was announced that the Mad Men and Handmaid’s Tale star Elisabeth Moss will play Jackson in a new movie based on Susan Scarf Merrell’s novel Shirley. It’s about a couple who move in with Jackson and her husband and wish they hadn’t.

Can You Name a Book?

Speaking of books, can you name one? If someone stopped you on the street and asked you to name a book — any book at all — could you do it? Of course you could! But these people interviewed on Jimmy Kimmel Live! had a lot more trouble.

RIP Philip Roth, Joseph Campanella, Clint Walker, Richard Goodwin, Robert Indiana, Jimmy Nickerson, and Patricia Morison

Philip Roth was one of the great writers of the 20th century, known for such novels as American Pastoral, Portnoy’s Complaint, Goodbye, Columbus, and many others. He died Tuesday at the age of 85.

Here’s a funny remembrance of meeting Roth from Billions creator Brian Koppelman.

Joseph Campanella was a veteran actor who appeared in dozens of TV shows and movies. He died last week at the age of 92.

Clint Walker starred in the popular western series Cheyenne from 1955 to 1962 and appeared in many other shows and movies. He died Monday at the age of 90.

Richard Goodwin was a speechwriter and adviser to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. He also wrote several books and was married to historian and author Doris Kearns Goodwin. He was a member of the House subcommittee that investigated rigged game shows in the late ’50s and was portrayed by Rob Morrow in the 1994 movie Quiz Show. He died Sunday at the age of 86.

Robert Indiana was an artist probably best known for his “LOVE” series of images in the 1960s. He died Saturday at the age of 89.

Jimmy Nickerson was a stuntman and actor who appeared in tons of classic movies and TV shows. He died earlier this month at the age of 68.

Patricia Morison was the original star of the Cole Porter musical Kiss Me, Kate in 1948 and went on to appear in many other stage productions and movies, including The Song of Bernadette, Song of the Thin Man, and the last Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes film, Dressed to Kill. She even appeared in an episode of Cheers. Morison died Sunday at the age of 103.

Quote of the Week

Not really a quote, it’s a headline, but it’s important news:

This Hawaii volcano sounds incredible. Via https://t.co/fVUSBNywwF pic.twitter.com/vxAQiRZNHx

— Tom Chivers (@TomChivers) May 18, 2018

This Week in History

Charles Lindbergh Takes Off (May 20, 1927)

Two months after the aviator made the first solo flight across the Atlantic, the Post honored Lindbergh with this Norman Rockwell cover.

Johnny Carson’s Last Tonight Show (May 22, 1992)

Carson was host of the NBC late night show for 30 years. Jay Leno took over the following Monday and didn’t thank Carson at all, a decision he called the biggest mistake of his career.

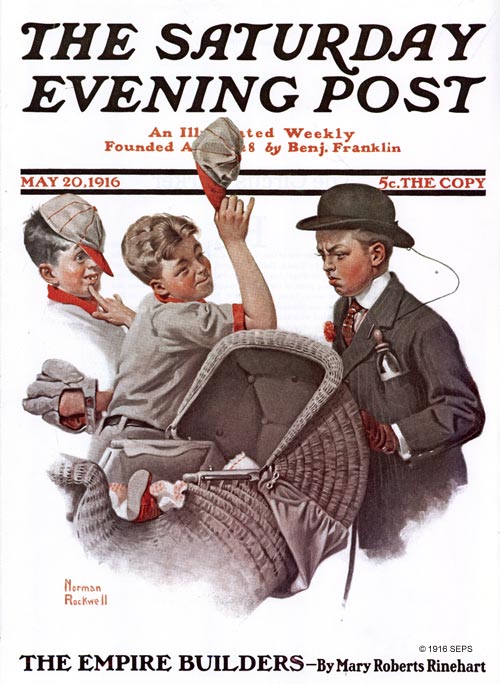

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: First Norman Rockwell Cover (May 20, 1916)

By: Norman Rockwell

May 20, 1916

Rockwell’s first cover was titled Boy with Baby Carriage. He also did the first full-color cover for the Post, The Old Sign Painter, in 1926.

French Food

The French Open tennis tournament starts Monday. There’s a big controversy this year because Serena Williams won’t be seeded due to the time she took off to have a baby. She was ranked number one when she left the tour and now she’s ranked 453, which means she’ll have to play the top players earlier. I think the moral to this story is “kids ruin everything.”

But let’s talk about French food. Here’s a classic recipe for Coq Au Vin from Bon Appétit and one for French Onion Soup Au Gratin. And because you can never have enough recipes with “au” in the name, here’s a recipe for Potatoes Au Gratin.

You can eat while watching the French Open coverage on NBC and the Tennis Channel, even if you will have to do it in the morning because of the time zone difference. But maybe it’s time Coq Au Vin became a breakfast staple.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Memorial Day (May 28)

Here’s Pamela Krol on what the day means and why it’s important to always remember.

Scripps National Spelling Bee (May 29)

You can watch all the preliminaries on ESPN3 starting at 9:15 a.m. and then the finals May 31 on ESPN2 starting at 10 a.m.

Last year’s winning word was marocain, which is a word I’ll probably never use, but it is an anagram of macaroni.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms

“We look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want … everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear … anywhere in the world.”

—President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress, January 6, 1941

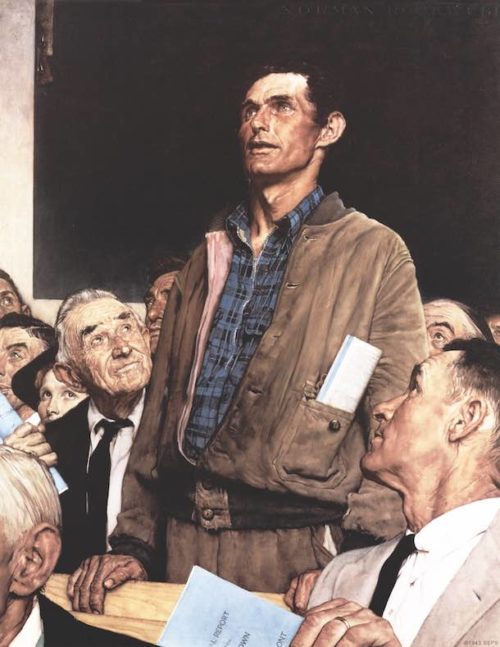

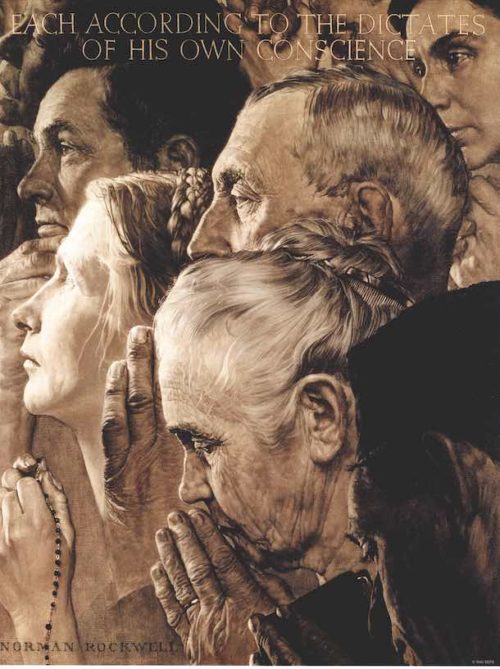

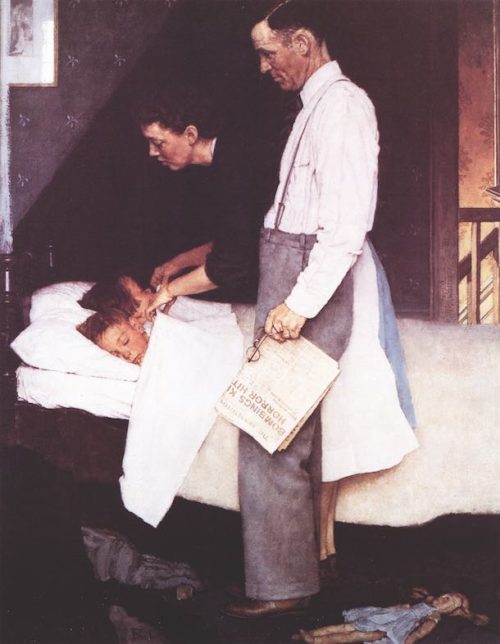

Inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous “Four Freedoms” speech to Congress on January 6, 1941, on the eve of World War II, Norman Rockwell wanted to contribute to the war effort by creating paintings that depicted each one.

The artist struggled with how best to visualize the abstract concepts. “I juggled the ‘Four Freedoms’ around in my mind, reading a sentence here, a sentence there, trying to find a picture,” he later recalled. “But it was so high-blown. Somehow I just couldn’t get my mind around it.”

One night in bed, Rockwell was mulling over the proclamation, getting more discouraged as hours ticked by. “I suddenly remembered how [neighbor] Jim Edgerton had stood up in a town meeting and said something that everybody else disagreed with,” Rockwell said. “They had let him have his say. No one had shouted him down. I thought — that’s it. Freedom of Speech — a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want — a Thanksgiving dinner. I’ll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes … in terms everybody can understand.”

Excited and confident, Rockwell rolled up his sketches and boarded a train for Washington, D.C., to visit the government’s propaganda department, the Office of War Information, proposing that the illustrations be made into patriotic posters that could be sold to raise funds for the war effort. “I showed the Four Freedoms to the man in charge of posters,” Rockwell said, “but he wasn’t even interested.” On his way back to Vermont, the discouraged artist stopped in Philadelphia to discuss future projects with Post editor Ben Hibbs. In passing, Rockwell mentioned his Washington trip, explained what the series was about, and then showed him the sketches. Hibbs loved the idea, telling the artist, “Norman, you’ve got to do them for us. … Drop everything else, just do the Four Freedoms.”

Rockwell spent seven months painting the Four Freedoms, which were published in four consecutive issues of the Post, starting on February 20, 1943, accompanied by essays by four distinguished writers — Booth Tarkington, Will Durant, Carlos Bulosan, and Stephen Vincent Benet. The paintings were a phenomenal success, with the Post receiving 25,000 reprint requests. A few months later, the government changed its tune, and in May 1943, the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department launched a joint fundraising campaign, sending the paintings on a 16-city national tour. More than one million people attended the exhibition that raised an astounding $132 million.

Now hanging in the Norman Rockwell Museum, the iconic paintings capture the freedoms we enjoy as Americans and the cherished ideals that unite us — timeless reminders of what we have and what we have to lose.

Freedom of Speech: Rockwell started the first painting in the series at least four times. He initially depicted an entire town meeting full of people, with one man standing up in the center of the crowd talking, but later felt “there were too many people in the picture.” He altered the composition significantly, tightening the focus on the speaker, now positioned in front of a blackboard, as townspeople listened respectfully to the speaker’s words.

Freedom of Worship: The original painting was set in a barbershop, with patrons of various races and religions patiently waiting their turns. “I wanted it to make the statement that no man should be discriminated against regardless of his race or religion,” Rockwell said. Ultimately, Rockwell rejected that scene as ambiguous. Instead, his finished composition groups faces and hands — a mélange of different cultures — in prayerful contemplation, bearing the legend, “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.”

Freedom from Want: One of Rockwell’s most famous and beloved works, Freedom from Want became an iconic representation of America’s quintessential national holiday, Thanksgiving. To create the scene, he grouped members of his own family and friends around a dinner table for a holiday meal. After two difficult paintings (Speech and Worship), this one came easy: “Mrs. Wheaton, our cook (and the woman holding the turkey), cooked it, I painted it, and we ate it.”

Freedom from Fear: The last in the series depicts children, oblivious to the mounting conflict in the world, resting safely in bed as their parents look on. The serenity of the scene is belied by the newspaper’s bold headline, “Bombing” — a reference the 1940–1941 blitz in London. Rockwell said the idea he hoped to convey was this: “Thank God we can put our children to bed with a feeling of security, knowing they will not be killed in the night.”

Rockwell’s Lasting Legacy

by Abigail Rockwell

We are living in chaotic and even alarming times, but here’s the tremendous gift: We are compelled to go within — so much outside of ourselves is beyond our control — to discover what our true values are — what is really important to us, for our families and our lives. Everything becomes clear in times of crisis. All of us are now urged to revisit the Four Freedoms and what they mean to us. Freedom of Speech (and the Press) is more relevant and vital than ever before; Freedom from Want — the polarity of the haves and the have-nots is starkly apparent and pressing; Freedom of Worship as everyone’s faith is being tested, judged, and at times viciously condemned; and Freedom from Fear haunts all of us as we attempt to gather greater strength, courage, and renewed purpose in the face of escalating troubles around the world.

The process of painting the Four Freedoms ushered in a new phase in my grandfather’s work; a greater sense of purpose, refined technique, and heightened storytelling began to inform his art from then on.

The great studio fire that occurred shortly after he completed Four Freedoms — a blaze that destroyed his entire studio and its contents, including the collection of his own work — forced him to immediately let go of the past and start all over again in the harsh light of an inestimable artistic and personal loss. But he embraced it, moved to a less isolated home on the West Arlington town green, and became very close with his neighbors — the Edgertons and the entire community in Vermont — which also greatly benefited his work and life.

Without his seven-month struggle in painting the Four Freedoms and the subsequent studio fire, the period of Norman Rockwell’s masterpieces in the late ’40s to mid-’50s simply would not have occurred.

To read the complete Four Freedoms essays, visit saturdayeveningpost.com/fourfreedoms.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Mort Künstler on Painting the American Adventure

Mort Künstler is revered today for his intricately detailed and painstakingly researched historical paintings, but those works tell only part of the story of his extraordinary 60–year career. This is a man who loves to paint, or rather lives to paint, a man who will tell you he gets as much satisfaction creating an ad for household soap as crafting a fine-art portrait of Lee and Grant at Appomattox. And indeed, before turning his attention to great moments in American history, Künstler took on all commissions, painting innumerable magazine illustrations — including for the Post — as well as advertisements, book covers, movie posters, even model kit box covers and stamps. In fact, if you think you don’t know his work, well, it’s almost certain that you’ve seen it in some form somewhere.

Künstler was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927. His parents recognized his talent at an early age and bought him art supplies and drawing lessons before he started school. Sickly as a young boy, he began exercising and developed into a talented athlete, becoming the first four-time letterman at Brooklyn College. After three years, he transferred to UCLA on a basketball scholarship, but soon returned home when his father suffered a heart attack. Back in New York, he enrolled in the Pratt Institute.

After graduating from Pratt with a certificate in illustration in 1950, Künstler quickly found work. Simply put, his artwork sold magazines, and publishers kept coming back for more.

Even as he was composing lurid covers for men’s adventure magazines (a soldier blasting his way through a pack of rabid wolves with a machine gun; a furious grizzly hoisting a hunter in its jaws), Künstler showed a knack for engaging the viewer in a human way reminiscent of Norman Rockwell. “Mort has the ability to express the power of the individual, often at a moment of triumph, confusion, or humor,” says Martin Mahoney, director of collections and exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum.

A 1966 assignment from National Geographic on the early history of the town of St. Augustine and another one on the discovery of San Francisco Bay would be game changers for the artist.

Employing his innate sense of drama, he brought these historic moments to life. Soon, he was painting scenes from the Civil War. Mahoney describes his own excitement when, as a boy, he was given a copy of Künstler’s Images of the Civil War. In the introduction to a major exhibition of Künstler’s work that Mahoney curated at the Norman Rockwell Museum, he describes the book as “a tipping point. … Suddenly the events of the era crystallized, and historical figures that lived, breathed, and died during this traumatic period of our country’s history became real.”

These historical paintings also reveal Künstler’s evolution as an artist, says Mahoney. “You see that he’s capturing that moment of excitement, which comes from adventure illustration, but he really began to develop his research chops as well as his artistic ones. He’s getting the saddles right; he’s getting the way the mule is loaded correctly; he’s got the way the cloaks will fall if you’re riding a horse.”

At 89, Künstler has no intention of slowing down. His paintings today fetch up to $250,000, and many adorn museum walls and are featured in traveling exhibitions, including a new one — Mort Künstler: The New Nation — at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York, running through April 2. I was able to squeeze in a phone call during a brief break in his busy work schedule.

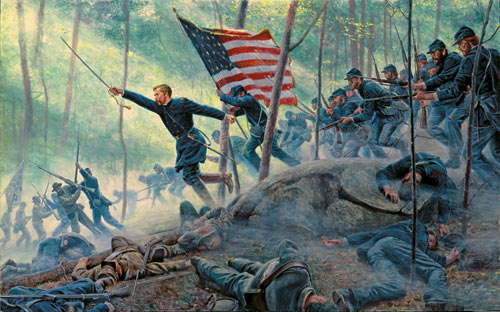

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, The Mud March © 2005 Mort Künstler, Inc.

Steven Slon: You’re a master of what’s often called narrative art — which is a fancy word for illustration. And you certainly are a rarity in the sense that most successful artists today, the ones whose work is in museums, tend to be abstract artists. But you, like Norman Rockwell, have always stayed true to the kind of art that tells a story.

Mort Künstler: I don’t know if you know this, but I own seven Rockwells.

SS: I did read that you were a collector and a fan.

MK: I am sitting in a room right now, looking at one of Rockwell’s magnificent Post covers from the ’30s. I also have the two full-scale charcoal drawings that he did from life of the two models. So the three works hang in a row here on this one wall. What’s so fascinating when I look at this picture is that I see the stuff that he changed from the studies that he did. Some of the changes I don’t even agree with, but every one was done for a reason — the folds in the clothing for the final version, for example.

You get to see the thinking. I just love that.

SS: What did you learn from studying Rockwell?

MK: The key thing is the way he creates a character. I am very conscious of characterization. And storytelling. It’s immediate, his storytelling ability. Also, people don’t understand what a great designer he is; he makes the eye go where he wants it to go. And that, too, I tried to learn from him. He uses every element, such as color, line, perspective — every device — to call attention to the story, never losing sight of the story. All this I learned from Rockwell and the other great illustrators, such as J.C. Leyendecker, who I also collect. Rockwell studied Leyendecker, who was another master of telling a story.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, Chamberlain’s Charge © 1994 Mort Künstler, Inc.

SS: Is there anything specific about how Rockwell painted that drew you to him?

MK: Hands are very difficult to do, probably more difficult than faces, and Rockwell’s hands were always impeccable. I always try to get hands in a picture, because hands can be as expressive as faces. I knew so many artists that would look for shortcuts; they would hide the feet in the tall grass and the hands in pockets. But I would put a hand on the guy’s chin if that’s what was needed, just to get hands in.

SS: What distinguishes your work from Rockwell’s?

MK: I do complex things, frequently with many more characters. I seem to have a knack for action and complexity to tell the story.

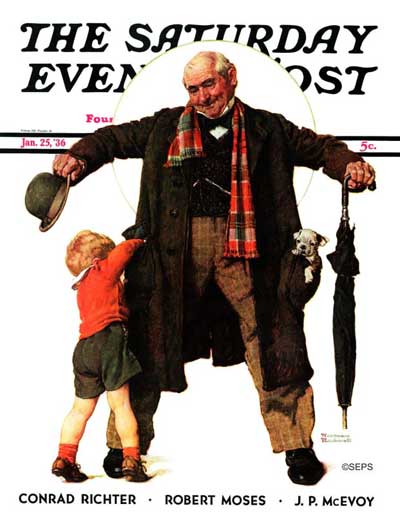

© SEPS; From the original painting by Mort Künstler

SS: Yes, Martin Mahoney, who curated your recent show at the Norman Rockwell Museum, pointed out that you have an ability to create these moments of intimacy, even in your cast-of-thousands Civil War battle scenes. Every one of your characters is real. They’re not just extras, not just generic soldiers.

MK: Well, Rockwell did that, too. He would be up on a ladder, for example, painting a scene at Grand Central Station or Penn Station, with crowds of people coming and going, and you look, and every character is different.

SS: Rockwell always considered himself an illustrator. What, if anything, is the distinction between fine art and illustration?

MK: You’re correct that Rockwell always said that he was an illustrator. But after all, so was Michelangelo — his page size was different, his art director was the pope, and his publisher was the church. So, to me, the biggest distinction is whether you’re commissioned to do the work or not. Some of the stuff they call fine art in museums is the worst garbage I’ve ever seen.

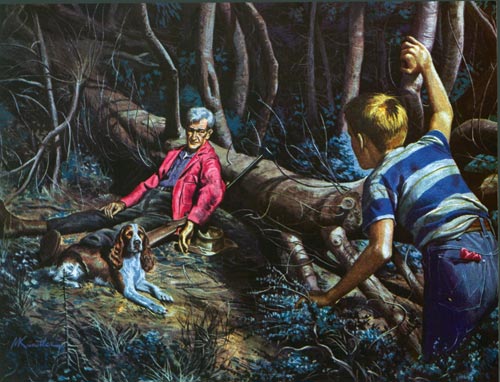

Jet-Sled Raid on Russia’s Ice Cap Pleasure Stockade © 1967 Mort Künstler, Inc.

SS: A question I asked Martin Mahoney, which I’m also putting to you, is, what causes an artist’s work to rise from a category of commercial excellence, let’s say, to being museum-worthy? He answered by pointing, in your case, to the way you evolved.

MK: Well, I started out in the early ’50s with all these men’s adventure magazines, which were flourishing at the time, and it was low-paying work, and I got a lot of it. And, because I was good at it, I ended up getting paid twice what everyone else did without asking for a raise. It seemed my covers sold the magazines, and other publishers started to call. What it did was start me off in this direction of action, complexity, and telling a story. If you look at everything throughout my career, you’ll see that it’s all based on this early training. That’s what prepared me to do all sorts of genres later.

The constant through my career is that I have enjoyed every minute of it. I remember doing some advertising art, a woman holding a cake of Camay soap. Now, advertising paid well, and it was very easy work compared to the men’s adventure magazines. But I had as good a time painting that as anything I’m painting today. I just enjoy pushing a paintbrush I guess.

SS: Other than the pleasure of painting, what else drives you?

MK: In the early days, what I think drove me was that I couldn’t believe that I was being paid to do this work. When I got my first job after art school, the illustration field was already dying. It was the ’50s and, as you know, the big magazines that still relied on illustration were the Post, Collier’s, and Liberty. But people were getting into TV, and magazines were just folding or turning to photography. But I was getting this work and making a good living. I couldn’t believe that, and when I saw my work getting reproduced, I was so thrilled. When I got my first check, I said to my wife, “I can’t believe they pay you for this!” Pretty soon, I was making quite a bit of money, but I was working all the time. There was no Saturday or Sunday. Now, I do take weekends off.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, The Shy Killer © 1955 Mort Künstler, Inc.

SS: You were quoted once as saying that the secret to being successful as an artist is the three H’s: the hand, the head, and the heart.

MK: When I say the hand, I mean you should be able to draw and paint; otherwise, you shouldn’t even be thinking about it. The head, you have to say, “By God, what can I do — given that everyone can draw or paint as well as me — what can I do that’s going to be different?” The heart part is, if you don’t have the passion or the desire to paint, then all the rest is gone.

SS: One of the things that’s fascinating about your work is that you create images that couldn’t be replicated by a camera.

MK: I always go with the premise, why bother with painting a picture if a photograph could do it? That was a major problem with the first space shuttle, because I was commissioned by Rockwell International to document it, and it ended up being the most photographed event in history. I think there were more than 2,000 photographers there. By examining it, looking at it in every possible way, I came up with the one angle that cameras could not get. It was from the point of view of an escape route that was kept clear so the astronauts could get out if something should happen on the launch pad. And of course, I painted another one from high above the shuttle looking down as it is being launched, another unique perspective.

SS: What are you working on these days?

MK: I have a big one in the works about baseball during the Civil War. About three years ago, I decided I’m not painting any more Civil War. I felt I had painted everything I had to paint on the subject. Turns out, I got drawn in again thanks to a book, Baseball in Blue and Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War. Now, most people think the sport developed later in the century, but baseball had actually become popular in the 1830s based on the English games of rounders and cricket, and by the 1860s it was quite popular. So my painting is of a game played on the White House lawn during the war. It’s an autumn scene, so the leaves are turning. There are pretty women in gowns watching the game. The men have taken their jackets off, and you can see that they’re servicemen. I’m very pleased with it so far.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, Launch of the Space Shuttle Columbia, April 12, 1981, 7:00:10 © 1981

SS: As you look back today on all your work, all you’ve accomplished, is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

MK: Not a thing. I will say that, early in my career, I worked myself to the point where we were doing very well financially, but I was ignoring my family. My wife was smart about it because she was on the verge of leaving me. That’s when I realized the men’s adventure magazine people wanted my work so much, and they were paying so well. Instead of just working all the time, I’d work half-time, and we’d enjoy ourselves with our three kids. So we picked up and moved the whole family to Mexico and lived there in 1962 and 1963. I did half of what I was doing before, and we spent our time traveling, having a good time. In fact, for a while, we even considered living there permanently. But after a year, we came back to the U.S. I look back upon that as a great experience, one of the best of my life.

So, no, I can’t say there’s anything I’d do over, anything at all. I’ve enjoyed it all the way, and I’m still in disbelief at my good fortune, because, really, I’ve never worked a day in my life.

Steven Slon is the editorial director for The Saturday Evening Post.

Christmas at Pop’s

(Image courtesy the Norman Rockwell Family Agency)

Christmas Day is on December 26. That’s what I thought my whole childhood, and even as an adult I continued to confuse it with the 25th. It’s because every year we went up to Pop’s house in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, the day after Christmas. Christmas at my grandfather Norman Rockwell’s was the highlight of that special season. They were the most magical Christmases of my life.

The memories are accompanied with such a vivid sensory awareness. We’d be greeted by Pop and my step-grandmother, Molly, at the kitchen door. The comforting smells of their cook Virginia’s food would surround and embrace us instantly. I would rush in to see the Christmas tree, running through the pantry, then through the hall with the creaky floorboard under the Arthur Rackham pen and ink, into the living room where I would stand in silence before the tree with its fresh pine scent. My favorite ornament was the little, gold guitar with actual strings and rhinestones, and I would search for it every year. The scent of the crackling fireplace in the library — where the adults would have their whiskey sours and the children would have ginger ale — hung in the air throughout the comfortable colonial house. I loved the after-dinner “job” of putting the candles out with the snuffer and watching the smoke mysteriously drift upwards from the extinguished flame. But what stays with me the most powerfully is the intoxicating scent of Pop’s pipe after he lit it, sitting in his big red armchair to the left of the fireplace. To this day on the rare occasion that I happen upon that scent, I am arrested by it and instantly taken back.

People would send my grandfather gifts every year. I remember winding up a music box in the bottom of a Scotch bottle and being entranced by the tiny Scottish dancer in a kilt turning to the tune of “Loch Lomond.” The Russian nesting dolls in the library were my favorite toy that I would play with faithfully, taking each doll out carefully and putting them together in a perfect lineup.

Norman Rockwell

January 25, 1936

Norman Rockwell’s Christmas paintings are some of his most charming and heartening. His connection to Christmas was deepened in his childhood by his Uncle Gil, an eccentric inventor and scientist. Uncle Gil would bring firecrackers at Christmas to celebrate the Fourth of July, Christmas presents on Easter, and chocolate rabbits on Thanksgiving. The next year he would turn things upside down again and bring chocolate rabbits hidden in his pockets for the children on Christmas. Uncle Gil was a character straight out of Charles Dickens [http://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2015/12/09/art-entertainment/art-and-artists/rockwells-dickensian-series.html], the great storyteller that had such a profound influence on my grandfather and his work. And I think somehow Uncle Gil became the embodiment of the Christmas spirit and this always stayed with Pop. He painted his memory of Uncle Gil in Little Boy Reaching in Grandfather’s Overcoat for The Saturday Evening Post cover, January 25, 1936. The little boy is my father, Thomas.

Home for Christmas (or, Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas) was painted for McCall’s December 1967 issue. It is one of my favorites. The main street of Stockbridge today still looks much the same. The little secret of the painting is the house with black shutters on the far right with all the windows illuminated and smoke coming out of its chimney — that was my grandfather’s home, with his barn red studio next to it, where we spent every Thanksgiving and Christmas. I still dream of that house.

It is easy to get lost in the details of this painting. It is full of life, movement and Yuletide festivity: children playing, shoppers with packages rushing home, cars in transit, people going into the library. But it is the less noticeable details that have always captured my interest. Some windows have candles in them, others don’t but instead have their blinds drawn. Some cars are parked correctly; others are a bit askew, presumably because the snow has erased the lines. I love the visible car tracks in the snow and all the different makes and models of automobiles; the newest one of that Christmas looks a bit like the Volkswagen Beetle, the blue car just left of the darkened inn.

The Red Lion Inn was closed at this time because it had fallen into neglect after one owner, Robert Wheeler, had misguidedly attempted to refashion it as a “motor lodge.” His endeavor failed and the inn went dark, intended for demolition in 1968; a gas station was planned in its place. It was saved by the Fitzpatrick family who purchased the inn that same year; they have run it ever since. Stockbridge is a small town of tradition and neighborly kindness and community — it is what Pop loved about it. That, and the wonderful townspeople he found to paint.

My grandfather’s first studio in Stockbridge was in the building with the big plate glass window with the Christmas tree. It was his studio from 1953–1957. He had the picture window installed to get the north light. At the very far left of the painting is The Old Corner House, the original site of the Norman Rockwell Museum, the white colonial with porch windows.

Pop painted the landscape with a delicate, primitive feel, choosing to layer somber transparent tones of grays and browns. The sky is the perfect cold winter sky after the sun has quickly set. All of these bleak colors serve as a contrast to the brilliant yellow light of the bustling town and vibrant Christmas decorations. It is through this important sense of contrast that the meaning of the holiday season is quietly illuminated — finding the light at the peak of the darkest month.

Many holiday blessings to everyone for a wonderful Christmas and Hanukkah! May the light we find in this season carry us through this next year and usher in a time of increased kindness and peace — in spite of everything we are facing around the world right now.

Warmest wishes,

Abigail

P.S. I just gave the Norman Rockwell Museum Archives my finalized, detailed list of the numerous errors and omissions in the recent fraudulent biography of Norman Rockwell, American Mirror, published in 2013. As many of you know, it is because of this biography that I was compelled to start my “Rescuing Norman Rockwell” Facebook page. The extensive list is not just a refutation of falsifications based on my investigation of the primary sources — it presents a true portrait of my grandfather and his life, including many details and memories that I learned from my father, Thomas Rockwell, Pop’s middle son. It will serve as a guide for future Norman Rockwell biographers and scholars. I am happy that this page that started out as a fight to have the truth heard has ended up being a celebration of Norman Rockwell and his work.

Special thanks to Laura Claridge for her comprehensive research in her 2001 biography, Norman Rockwell, A Life. Her biography was a considerable help to me in my investigation.

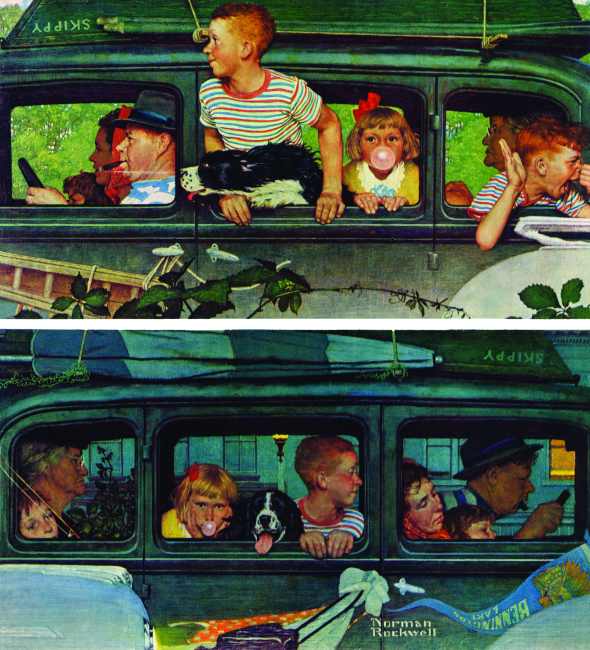

Road Trip!

After WWII ended, America was on the move. With an economy on an upswing and higher levels of disposable income, record numbers of families packed up the station wagon, loaded kids in the backseat, and hit the open highway.

Norman Rockwell celebrated the emerging trend in the August 30, 1947, Post cover Going and Coming. While seasonal or topical subjects often inspired Rockwell’s covers, in this two-panel portrait of a family en route to and from a summertime trip we find an example that’s both.

In Going, Dad confidently grips the wheel leading the expedition with Mom at his side cradling the youngest. Anticipation spills into the backseat where big brother and pooch lean into the wind, while little sister blows a bubble about to pop as her brother razzes oncoming cars. Unfazed by it all, Grandma sits stone-faced, staring straight ahead.

In Coming, the excitement has fizzled. Pop struggles to keep his eyes open. Mom, still cradling little sis, drifted off miles ago, while the boys, pooch, even the wide-eyed bubble blower are running out of steam. Unfazed by it all, Grandma sits stone-faced, staring straight ahead — did she even get out of the car?

To help readers unravel the story line, Rockwell provides clues. In the lower panel, to signify nighttime, he shows the tiniest portion of a lighted lamppost through the car window. Another clue: The pennant dangling from the door tells us the outing was to Bennington Lake, where — judging from the fishing pole sticking out the rear window and weathered rowboat lashed to the roof — Dad managed to get in some angling. Rockwell also lets us know Grandma indeed exited the car — if only for a souvenir plant.

There’s a familiar feeling to the entire scene. (We’ve all been on family outings like this.) You can almost hear the eternal refrain, “Are we there yet?”

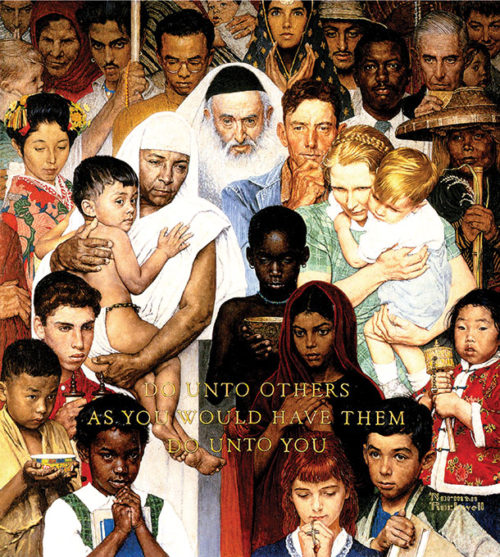

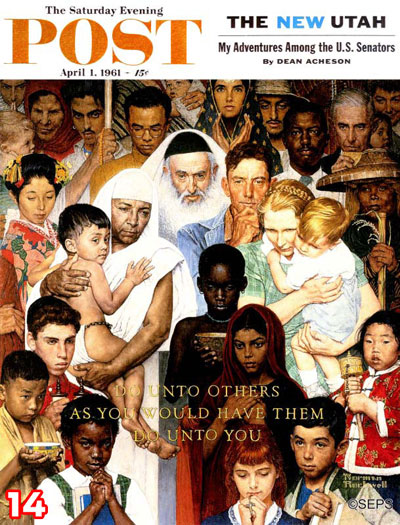

Something Serious

For Norman Rockwell, the 1960s marked a period of change. The mood of the country was shifting. The rising popularity of television in American homes fed a culture fascinated with celebrity. Catering to popular taste, many magazines began using photographic covers (frequently portraits) in place of illustration. While he would hold his position as the Post’s premier illustrator for a few more years, Rockwell could see the writing on the wall. At the same time, on a personal level, Rockwell was still mourning his wife, Mary, who died suddenly in August 1959.

During this period, the artist began to explore social issues. “Most of the time, I try to entertain with my Post covers,” Rockwell said. “Once in a while I get an uncontrollable urge to say something serious.”

In the summer of 1960, inspired by the idea that the Golden Rule was a universal principle threading through all religions, Rockwell decided to capture the concept on canvas.

After preliminary sketches, he remembered an earlier piece, United Nations, that had never been completed. He found the unfinished 10-foot-long charcoal in the cellar and hauled it upstairs to his studio. “I had tried to depict all the peoples of the world gathered together,” Rockwell said. “That was just what I wanted to express about the Golden Rule.”

Some portraits were repainted from the original charcoal. Others were created afresh, using neighbors as models. The rabbi (center) was Stockbridge’s retired postmaster (a Catholic in real life); and Rockwell’s late wife, Mary, appears to his right holding the grandchild she never saw.

The work appeared on the April 1, 1961, cover of the Post. Reader response was overwhelmingly positive.

As a testament to the power of the image, a mosaic based on the painting was installed at the United Nations Headquarters in 1985. It was rededicated following its restoration in 2014.

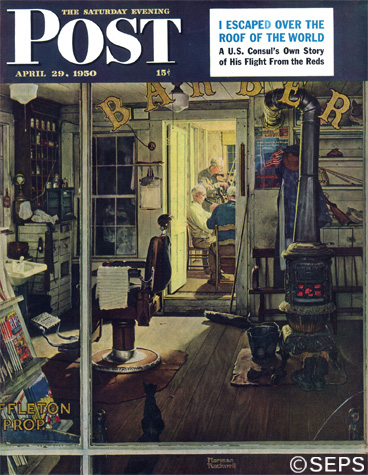

Rockwell Painting Inspires Movie

Norman Rockwell

April 29, 1950

The painting is one of the most intricately detailed works from an illustrator with a mania for minutiae: faithfully reproduced ironwork scrolling on the barber chair and cozy stove, comic books on the rack, and chipped paint on a windowpane molding. The painting “stands as one of the finest displays of Norman Rockwell’s talent as an artist,” says Jeremy Clowe of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

For all the painting’s detail and masterful lighting and composition, it is the after-hours peek into the back room that draws us, as barber trades his scissors and razor for a cello to make music with his friends.

Echoes of Rockwell’s painting appear in the new movie A Way Back Home, a Hallmark Movie Channel original starring four-time Emmy nominee Danny Glover as barber Charlie Shuffleton and Austin Stowell as Trey Cole, a celebrity coming to the realization that he has lost himself along the way.

Trey has severed ties with his past and didn’t even return home when his brother died serving in the military. But now memories are stirring, like that old barbershop and his first haircut in the brown leather chair and how Charlie (Glover) took him under his wing when he was a boy, when his own father was cold and often absent. Returning to the barbershop in one of the film’s opening scenes, Trey notices a trio of musicians playing in a dimly lit back room as in Rockwell’s original painting.

“For his cover illustration for the April 29, 1950, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell turned to Rob Shuffleton’s barbershop in East Arlington, Vermont,” said Clowe.

Yes, Shuffleton’s Barbershop was a real place; it was where America’s favorite artist went for a trim. “Similar to how he employed both neighbors and family as subjects for his work, Rockwell also found artistic inspiration from his surroundings,” Clowe explains.

The cello player sitting in the interior room is Rob Shuffleton, whom Rockwell once called “a tonsorial virtuoso who always trims his locks exactly the right length.” Shuffleton’s Barbershop was a place, like the little town of Arlington, Vermont, itself, where a world-famous artist could go and be treated like everyone else—just the way he liked it.

As you watch the movie, which premiered Saturday, June 1, look for ways Rockwell’s painting inspired the feature-length film.

Purchase a print of Norman Rockwell’s Shuffleton’s Barbershop at Art.com.

Peter Rockwell: A Sculptor’s Retrospective

Norman Rockwell’s three boys—Jerry, Tom, and Peter—showed up on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post more than half a dozen times.

His youngest son Peter had no interest in pursuing a career as an artist. But after taking a sculpture class in college, he was hooked. In this video, Peter tells us about his inspirations, influences, and memories of growing up with the Rockwells.

Courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

A Day in the Life of Norman Rockwell Model Chuck Marsh

At the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, visitors can chat with former Rockwell models the first Friday of each month. Chuck Marsh Jr., who was the model for A Day in the Life of a Boy from 1952, recently discussed what it was like working with Rockwell.

Courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

Norman Rockwell: Getting the Real Picture

There is almost a Shaker aesthetic to the old Stockbridge, Massachusetts, studio where Norman Rockwell once worked. “One thing that surprises people, even our staff, is just how spare the space was,” says the Norman Rockwell Museum’s chief curator and deputy director, Stephanie Plunkett. “Rockwell was extremely neat. He cleaned up several times a day. Generally there wasn’t a lot of clutter around.”

The sparseness is still there in the old studio that has been on display for more than two decades. Hundreds of thousands of visitors have toured the one-room structure, seeing it pretty much as it looked at the time of the artist’s death in 1978. But beginning in May, visitors will have a new experience, one that Plunkett says will be more representative of “what Rockwell’s work life was really like.” Thanks to a cache of faded old negatives in the museum’s archives, the staff have been able to recast the studio as it looked nearly two decades earlier in October of 1960. That was the month when Nikita Khrushchev pounded his shoe on a table at the United Nations in New York, and by coincidence, Rockwell was at work in his studio on a cover painting based on a United Nations scene, The Golden Rule.

An over zealous photographer hired by the artist at the time captured the unfinished painting on film as it sat on Rockwell’s easel. Not only did he take pictures of the painting, but of everything else in the room as well.

For the past year, museum staff have been studying those photos and bringing all the pieces together to reinstall the studio exactly as it was. And the whole, as they say, is more engaging than the sum of its parts. Rockwell’s work life and personal life came together in his studio, and if you know what to look for, it can be seen in his finished works.

Visitors will now be able to view the unfinished painting that depicts the Biblical injunction: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. (The Golden Rule painting eventually appeared on the April 1, 1961 cover of The Saturday Evening Post.) Around Rockwell’s easel viewers will see mounted some of the model photos and magazine pictures the artist was using for the people in the painting. Some faces were simply transferred from the original, unfinished U.N. drawing, which can be seen on the floor of the studio. Others, notes the curator of archival collections, Corry Kanzenberg, were modeled from Rockwell’s Stockbridge neighbors. “His assistant’s daughter was the model for the girl at the bottom of the painting with red hair, holding a rosary,” she says. The Rabbi with the big white beard at the center of the painting was actually Stockbridge’s retired postmaster. Rockwell added the beard and the religion; the man was actually a Catholic.

In the top right-hand corner of the painting, one can see Rockwell’s most personal touch, he has added the image of his late wife, Mary, who had died the previous year. She is holding their first grandson that she never lived to see.

Numerous mementos of Mary appear in the old photos, Kanzenberg says, including an abstract pastel painting she had created for an art course. The original no longer survives, but a local artist was hired to paint an exact replica from the single old faded color transparency that existed of the painting.

Other items that needed replacing, says Kanzenberg, included an old Philco radio and a large cylindrical tobacco can seen on a desk by the west wall. The staff located identical items on eBay. The old radio still worked.

For an added touch of authenticity the exhibit now even features sound—a mock broadcast will play the favorite music the artist liked listening to on the radio as he worked perfecting his paintings—all opera.

“People who were there recall Rockwell listening to opera as he worked,” Kanzenberg says. “We have been having fun figuring out what opera he might have heard.” The program includes selections from Verdi’s Nabucco that premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in October of 1960 as well as recordings by Emmy Destinn and Enrico Caruso, performers Rockwell actually interacted with as a young art student when he worked part-time as an extra at the Met.

As they listen to the music, visitors will tread a new path through the studio over a hand-dyed rug, an exact reproduction by the same company that made the studio rug Rockwell used for years. “We are allowing visitors to move into the central part of the room, where before they were only able to walk along a straight path,” says Plunkett. “I think it’s going to be a lot of fun because they can really see interesting details, such as all of the materials that were on his desk where his secretary answered his fan mail. They can see the writing on the wall around his Princess telephone including his analyst’s phone number. It will be a more intimate experience.”

Fortieth Anniversary

The new studio exhibit, A Day in the Life: Norman Rockwell’s Stockbridge Studio, is one element of the Norman Rockwell Museum’s 40th anniversary celebration. In July, as part of the special year marking the museum’s founding in 1969, American Chronicles, a traveling major retrospective of Norman Rockwell’s life and work, will return to Stockbridge from July 4 through September 7 before continuing on around the country. Also in November, the museum will launch the “first wave” of its Project NORMAN online digitized archive, making 40,000 items from its 200,000-item collection of photographs, objects, and documents available to scholars and the public worldwide at the Museum’s Web site.