Mort Künstler is revered today for his intricately detailed and painstakingly researched historical paintings, but those works tell only part of the story of his extraordinary 60–year career. This is a man who loves to paint, or rather lives to paint, a man who will tell you he gets as much satisfaction creating an ad for household soap as crafting a fine-art portrait of Lee and Grant at Appomattox. And indeed, before turning his attention to great moments in American history, Künstler took on all commissions, painting innumerable magazine illustrations — including for the Post — as well as advertisements, book covers, movie posters, even model kit box covers and stamps. In fact, if you think you don’t know his work, well, it’s almost certain that you’ve seen it in some form somewhere.

Künstler was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927. His parents recognized his talent at an early age and bought him art supplies and drawing lessons before he started school. Sickly as a young boy, he began exercising and developed into a talented athlete, becoming the first four-time letterman at Brooklyn College. After three years, he transferred to UCLA on a basketball scholarship, but soon returned home when his father suffered a heart attack. Back in New York, he enrolled in the Pratt Institute.

After graduating from Pratt with a certificate in illustration in 1950, Künstler quickly found work. Simply put, his artwork sold magazines, and publishers kept coming back for more.

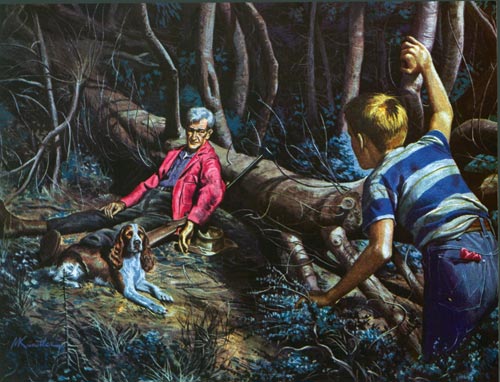

Even as he was composing lurid covers for men’s adventure magazines (a soldier blasting his way through a pack of rabid wolves with a machine gun; a furious grizzly hoisting a hunter in its jaws), Künstler showed a knack for engaging the viewer in a human way reminiscent of Norman Rockwell. “Mort has the ability to express the power of the individual, often at a moment of triumph, confusion, or humor,” says Martin Mahoney, director of collections and exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum.

A 1966 assignment from National Geographic on the early history of the town of St. Augustine and another one on the discovery of San Francisco Bay would be game changers for the artist.

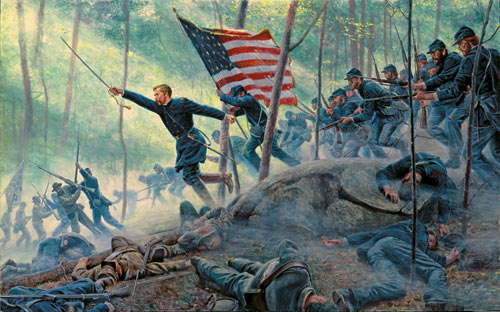

Employing his innate sense of drama, he brought these historic moments to life. Soon, he was painting scenes from the Civil War. Mahoney describes his own excitement when, as a boy, he was given a copy of Künstler’s Images of the Civil War. In the introduction to a major exhibition of Künstler’s work that Mahoney curated at the Norman Rockwell Museum, he describes the book as “a tipping point. … Suddenly the events of the era crystallized, and historical figures that lived, breathed, and died during this traumatic period of our country’s history became real.”

These historical paintings also reveal Künstler’s evolution as an artist, says Mahoney. “You see that he’s capturing that moment of excitement, which comes from adventure illustration, but he really began to develop his research chops as well as his artistic ones. He’s getting the saddles right; he’s getting the way the mule is loaded correctly; he’s got the way the cloaks will fall if you’re riding a horse.”

At 89, Künstler has no intention of slowing down. His paintings today fetch up to $250,000, and many adorn museum walls and are featured in traveling exhibitions, including a new one — Mort Künstler: The New Nation — at the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York, running through April 2. I was able to squeeze in a phone call during a brief break in his busy work schedule.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, The Mud March © 2005 Mort Künstler, Inc.

Steven Slon: You’re a master of what’s often called narrative art — which is a fancy word for illustration. And you certainly are a rarity in the sense that most successful artists today, the ones whose work is in museums, tend to be abstract artists. But you, like Norman Rockwell, have always stayed true to the kind of art that tells a story.

Mort Künstler: I don’t know if you know this, but I own seven Rockwells.

SS: I did read that you were a collector and a fan.

MK: I am sitting in a room right now, looking at one of Rockwell’s magnificent Post covers from the ’30s. I also have the two full-scale charcoal drawings that he did from life of the two models. So the three works hang in a row here on this one wall. What’s so fascinating when I look at this picture is that I see the stuff that he changed from the studies that he did. Some of the changes I don’t even agree with, but every one was done for a reason — the folds in the clothing for the final version, for example.

You get to see the thinking. I just love that.

SS: What did you learn from studying Rockwell?

MK: The key thing is the way he creates a character. I am very conscious of characterization. And storytelling. It’s immediate, his storytelling ability. Also, people don’t understand what a great designer he is; he makes the eye go where he wants it to go. And that, too, I tried to learn from him. He uses every element, such as color, line, perspective — every device — to call attention to the story, never losing sight of the story. All this I learned from Rockwell and the other great illustrators, such as J.C. Leyendecker, who I also collect. Rockwell studied Leyendecker, who was another master of telling a story.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, Chamberlain’s Charge © 1994 Mort Künstler, Inc.

SS: Is there anything specific about how Rockwell painted that drew you to him?

MK: Hands are very difficult to do, probably more difficult than faces, and Rockwell’s hands were always impeccable. I always try to get hands in a picture, because hands can be as expressive as faces. I knew so many artists that would look for shortcuts; they would hide the feet in the tall grass and the hands in pockets. But I would put a hand on the guy’s chin if that’s what was needed, just to get hands in.

SS: What distinguishes your work from Rockwell’s?

MK: I do complex things, frequently with many more characters. I seem to have a knack for action and complexity to tell the story.

© SEPS; From the original painting by Mort Künstler

SS: Yes, Martin Mahoney, who curated your recent show at the Norman Rockwell Museum, pointed out that you have an ability to create these moments of intimacy, even in your cast-of-thousands Civil War battle scenes. Every one of your characters is real. They’re not just extras, not just generic soldiers.

MK: Well, Rockwell did that, too. He would be up on a ladder, for example, painting a scene at Grand Central Station or Penn Station, with crowds of people coming and going, and you look, and every character is different.

SS: Rockwell always considered himself an illustrator. What, if anything, is the distinction between fine art and illustration?

MK: You’re correct that Rockwell always said that he was an illustrator. But after all, so was Michelangelo — his page size was different, his art director was the pope, and his publisher was the church. So, to me, the biggest distinction is whether you’re commissioned to do the work or not. Some of the stuff they call fine art in museums is the worst garbage I’ve ever seen.

Jet-Sled Raid on Russia’s Ice Cap Pleasure Stockade © 1967 Mort Künstler, Inc.

SS: A question I asked Martin Mahoney, which I’m also putting to you, is, what causes an artist’s work to rise from a category of commercial excellence, let’s say, to being museum-worthy? He answered by pointing, in your case, to the way you evolved.

MK: Well, I started out in the early ’50s with all these men’s adventure magazines, which were flourishing at the time, and it was low-paying work, and I got a lot of it. And, because I was good at it, I ended up getting paid twice what everyone else did without asking for a raise. It seemed my covers sold the magazines, and other publishers started to call. What it did was start me off in this direction of action, complexity, and telling a story. If you look at everything throughout my career, you’ll see that it’s all based on this early training. That’s what prepared me to do all sorts of genres later.

The constant through my career is that I have enjoyed every minute of it. I remember doing some advertising art, a woman holding a cake of Camay soap. Now, advertising paid well, and it was very easy work compared to the men’s adventure magazines. But I had as good a time painting that as anything I’m painting today. I just enjoy pushing a paintbrush I guess.

SS: Other than the pleasure of painting, what else drives you?

MK: In the early days, what I think drove me was that I couldn’t believe that I was being paid to do this work. When I got my first job after art school, the illustration field was already dying. It was the ’50s and, as you know, the big magazines that still relied on illustration were the Post, Collier’s, and Liberty. But people were getting into TV, and magazines were just folding or turning to photography. But I was getting this work and making a good living. I couldn’t believe that, and when I saw my work getting reproduced, I was so thrilled. When I got my first check, I said to my wife, “I can’t believe they pay you for this!” Pretty soon, I was making quite a bit of money, but I was working all the time. There was no Saturday or Sunday. Now, I do take weekends off.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, The Shy Killer © 1955 Mort Künstler, Inc.

SS: You were quoted once as saying that the secret to being successful as an artist is the three H’s: the hand, the head, and the heart.

MK: When I say the hand, I mean you should be able to draw and paint; otherwise, you shouldn’t even be thinking about it. The head, you have to say, “By God, what can I do — given that everyone can draw or paint as well as me — what can I do that’s going to be different?” The heart part is, if you don’t have the passion or the desire to paint, then all the rest is gone.

SS: One of the things that’s fascinating about your work is that you create images that couldn’t be replicated by a camera.

MK: I always go with the premise, why bother with painting a picture if a photograph could do it? That was a major problem with the first space shuttle, because I was commissioned by Rockwell International to document it, and it ended up being the most photographed event in history. I think there were more than 2,000 photographers there. By examining it, looking at it in every possible way, I came up with the one angle that cameras could not get. It was from the point of view of an escape route that was kept clear so the astronauts could get out if something should happen on the launch pad. And of course, I painted another one from high above the shuttle looking down as it is being launched, another unique perspective.

SS: What are you working on these days?

MK: I have a big one in the works about baseball during the Civil War. About three years ago, I decided I’m not painting any more Civil War. I felt I had painted everything I had to paint on the subject. Turns out, I got drawn in again thanks to a book, Baseball in Blue and Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War. Now, most people think the sport developed later in the century, but baseball had actually become popular in the 1830s based on the English games of rounders and cricket, and by the 1860s it was quite popular. So my painting is of a game played on the White House lawn during the war. It’s an autumn scene, so the leaves are turning. There are pretty women in gowns watching the game. The men have taken their jackets off, and you can see that they’re servicemen. I’m very pleased with it so far.

From the original painting by Mort Künstler, Launch of the Space Shuttle Columbia, April 12, 1981, 7:00:10 © 1981

SS: As you look back today on all your work, all you’ve accomplished, is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

MK: Not a thing. I will say that, early in my career, I worked myself to the point where we were doing very well financially, but I was ignoring my family. My wife was smart about it because she was on the verge of leaving me. That’s when I realized the men’s adventure magazine people wanted my work so much, and they were paying so well. Instead of just working all the time, I’d work half-time, and we’d enjoy ourselves with our three kids. So we picked up and moved the whole family to Mexico and lived there in 1962 and 1963. I did half of what I was doing before, and we spent our time traveling, having a good time. In fact, for a while, we even considered living there permanently. But after a year, we came back to the U.S. I look back upon that as a great experience, one of the best of my life.

So, no, I can’t say there’s anything I’d do over, anything at all. I’ve enjoyed it all the way, and I’m still in disbelief at my good fortune, because, really, I’ve never worked a day in my life.

Steven Slon is the editorial director for The Saturday Evening Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The interview with Kunstler is wonderful. His masterful work in all these different genres is astonishing. He certainly learned from the best, Rockwell and Leyendecker. I love the covers of the men’s magazines and movie posters, but the Civil War illustrations most of all. His latest venture already sounds like a new classic in the making.