Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Catastrophic Predictions and Labeling Won’t Help You Lose Weight

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

In the last few posts we’ve been reviewing thoughts that might interfere with achieving health goals, including all-or-nothing thinking, mind reading, and filter focus. This week we will explore catastrophic predictions and labeling.

Catastrophic Predictions

“If I don’t lose weight now, I never will.”

“Really? Why do you say that? I asked.”

“My doctor told me I’m no longer pre-diabetic; I actually have diabetes. My knees hurt and I take six different medications every day. If that isn’t enough motivation, nothing will ever get my butt in gear.”

The idea that you’ll never lose weight if you don’t do it now is a good example of a catastrophic prediction. This way of thinking creates enormous pressure to change. Although this pressure can yield results in the short run, it doesn’t work well as a long-term perspective. A now-or-never mindset builds resentment and is emotionally exhausting. You may believe that putting intense pressure on yourself to change NOW will eventually lead to healthy habits. But our minds don’t work that way. Think about anything you were pressured to do as a child (play a sport, take piano lessons). If you didn’t begin enjoying yourself or grasp its value early in the process, you probably fizzled out before long. As we will discuss later, choice is much easier to sustain than pressure.

Catastrophic predictions in other areas of our lives also create anxiety. The single mom in the inner city may believe that if her child doesn’t do his homework every single night he’ll end up on drugs or in prison. This thought process causes her to feel anxious, and as a result of her fear, she pressures her son over doing homework. Her approach is not calm and supportive, but instead demanding and authoritarian. Unfortunately, this method probably won’t yield a happy homework time or a love of academic pursuits for her son — unless she can also instill in him the value of an education.

Labeling

“So Bob, tell me why you’ve had trouble getting into a regular exercise routine.”

“That’s an easy question. I’m just lazy.”

Lightheartedly, I responded, “Well, I have to be honest with you — I can’t fix lazy! Let me ask you a few other questions. You have a job, right?”

Bob nods his head. “Yep, two more years ‘til I can retire.”

“Kids?”

“Three of them, and all out of the house. I’ve got two grandkids thanks to my oldest son and his wife.”

“Do you get to spend much time with your grandkids?”

Bob leaned back in his chair and chuckled. “They live nearby and it’s one of the greatest pleasures in my life. I take my 7-year-old grandson fishing almost every weekend in the summer. My 4-year-old granddaughter — now she’s a piece of work — she likes to come over and ride on the tractor with me.”

“So they love spending time with their grandpa!”

“Oh, you betcha.” He leaned forward as though telling me a secret. “Last time after they were over they asked their mom if they could move in with us.” Bob sat back and pushed his glasses back towards his face. “I guess we’d have room. Heck we have ten acres, we could build on if we wanted!”

“It sounds like there’s a lot to take care of at home. Do you mow most of the land?”

“I mow about two acres, the rest is just woods — my granddaughter would tell you she mows the yard.”

“What do you do in your free time?”

“I don’t have much of it, but I like to tinker with my motorcycle.”

“So you don’t just sit around with your feet up and have people wait on you?”

Bob started laughing, “No, no. I see where you’re going.”

“Okay, so we’ve established you are not lazy, so let’s talk about the real reasons you struggle with exercising regularly.”

In situations like Bob’s, the reason he doesn’t exercise may be related to some combination of not enjoying it, lacking time, not knowing what to do, not having a past history of exercising, or not seeing the benefits. Labeling himself “lazy” is inaccurate and does nothing to solve the problem.

Likewise, labeling someone a “jerk” does nothing to define problems with the relationship. Therefore, the relationship probably won’t improve. Saying you failed a test because you’re stupid prevents you from looking at the real reason you didn’t perform well.

In most instances, labeling is a poor way of explaining our behavior. We are unintentionally reasoning our way out of a solution. In other situations, using labels can be a copout. When you label yourself stupid, lazy, disorganized, or lacking willpower, you’re saying you can’t change — and that lets you off the hook for managing your weight. Labeling other people as jerks means you can’t fix the relationship, so why bother trying?

New Math: When the Indiana Legislature (Almost) Changed Pi

Today is Pi Day, the day we recognize the wonder of 3.14. Since 200 B.C., we’ve known we can calculate the area of a circle by (1) squaring the distance from the circle’s center to its edge, then (2) multiplying this value by 3.14 — the value of pi.

This number is the ratio of every circle’s circumference to its diameter. An irrational number, pi contains an infinite number of numbers behind the decimal point. (You can find it calculated to the 100,000th digit here.)

Back in 1894, an amateur mathematician in Solitude, Indiana, thought there had to be a better way to measure a circle’s area. Edward Goodwin believed that, using a compass and a ruler, he could create a square with the same area as a circle. And a square’s area would be so much easier to measure.

There was one problem with his method. It didn’t work. In fact, 12 years earlier, a mathematician had proven, mathematically, that it was impossible to calculate the area of a circle this way.

One reason Goodwin’s method didn’t work is that it changed the value of pi from 3.141592 etc. to 3.2. (As he expressed it, “The ratio of the diameter and circumference is as five-fourths to four.”)

Enchanted by his own genius, Goodwin copyrighted his method. Now he could earn a royalty whenever businesses and schools used his new, improved system.

But he knew the state of Indiana couldn’t afford the royalties that introducing his system into Indiana’s schools would involve. So he offered the state a deal: If Indiana’s legislature would officially acknowledge the validity of his system, he’d waive the royalty fees.

Representative Taylor I. Record was Goodwin’s state representative, and he thought it a generous offer. So, in 1897, he introduced House Bill 246, which declared, “a circular area is to the square on a line equal to the quadrant of the circumference, as the area of an equilateral rectangle is to the square on one side.”

If that sounds confusing to you, you’re not alone. Many legislators didn’t understand it either. Nonetheless, they passed the bill in the state House on February 5, 1897. Unanimously. No one stood up and said, “Wait. I’m not supporting this until I understand it.”

The Indianapolis newspapers were wholly supportive of Goodwin’s theory, though it appears they didn’t understand it any better than the legislators did.

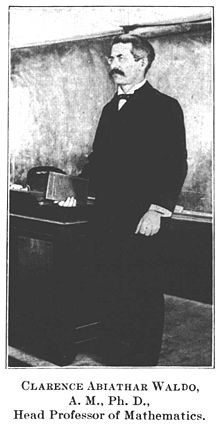

And so the bill moved on to the Senate. Fortunately, a math professor from Purdue University was coincidentally in the capitol building when the bill was being debated. Professor Clarence Abiathar Waldo was aghast to hear the state might make this erroneous theory part of school curriculum. He cornered some senators to ask about the bill. They offered to introduce him to the learned Goodwin. Waldo declined, saying that he’d already met as many crazy people as he cared to know.

He explained to the senators why Goodwin’s method was flawed. Armed with this knowledge, they took to the Senate floor to mock the bill and Goodwin’s theory. Finally, a senator moved to postpone the bill. It was never brought up again.

It was easy to make fun of the idea after Waldo had spoken up. Even the newspapers changed their tune. The Indianapolis Journal observed, “The Senate might as well try to legislate water to run up hill as to establish mathematical truth by law.

Featured image: Shutterstock