A New Wave of Board Games is Breaking Parker Brothers’ Rules

Of all the industries shaken and destroyed by the fast-paced development of technology, one would assume board games to be sunk by their video counterparts. In reality, “tabletop gaming” is in the midst of a golden age. According to The Guardian, sales of board games is rising 25% to 40% each year.

Millennials aren’t necessarily playing Parcheesi, though. The new wave of games includes titles like Secret Hitler, Ex Libris, Dragonfire, and Pandemic. On the rise are role-playing games, connection games, Eurogames, and, sometimes, analog versions of existing video games, like Fallout and Sid Meier’s Civilization. Many are steeped in complicated fantasy worlds with Vikings and labyrinthine backstories, but others are simple logic contests. Still more are not competitive at all and only aim for players to work together in pursuit of a desirable conclusion. Yes, everyone can lose.

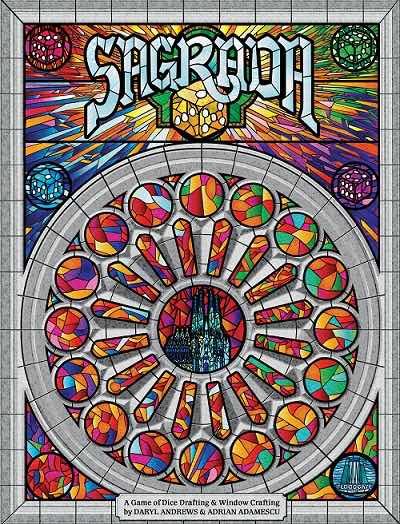

The internet has played a significant role in this revolution, creating a space for independent game makers to fund and sell their ideas. The independent tabletop game company Floodgate Games released their Spanish basilica-inspired dice game, Sagrada, this year after a Kickstarter campaign that raised over $150,000. The visually striking board game involves using colored dice to “construct a stained-glass masterpiece” with rules reminiscent of Sudoku.

Another Kickstarter success was the wildly popular — and risqué — Cards Against Humanity: A Party Game for Horrible People. Derivative of the family card-comparison game Apples to Apples, Cards Against Humanity ditched wholesome cultural and historical references for politically incorrect phrases like “demonic possession” or “a homoerotic volleyball montage,” or “actually taking candy from a baby.” The ribald and racy game earned an estimated $12 million in its first two years of production despite being free for download online (1.5 million downloads took place as well). The small Chicago group in charge of the debauchery continues to churn out expansion card decks, and they refuse to sell the brand.

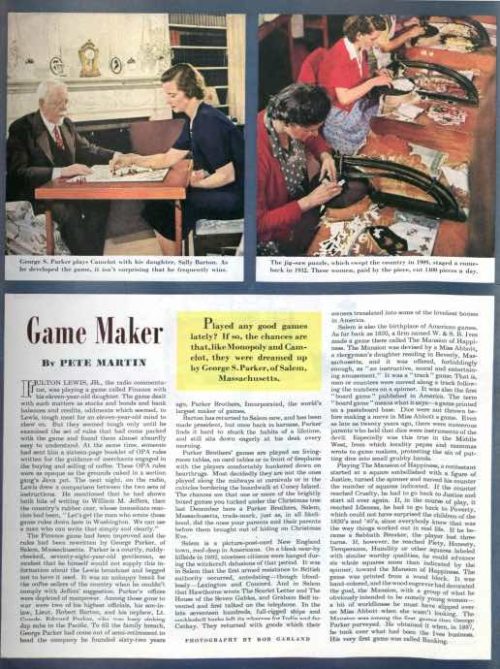

Small-time board game publishers have seen enormous success given a platform to market and sell their games. This wasn’t always viable, though, with tabletop gaming. At the advent of commercial board gaming in the U.S., the late-1800s, Parker Brothers was the big name in board game development and manufacturing. Early games like Banking and Mansion of Happiness rewarded capitalistic pursuits and moral values.

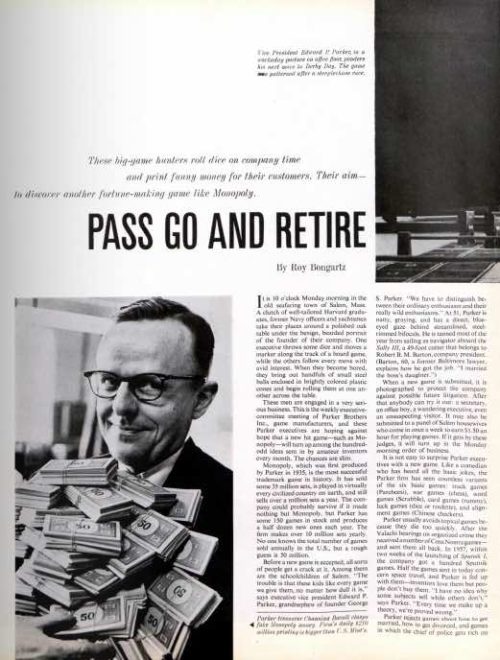

In a Post story from 1966, “Pass Go and Retire,” Parker Brothers executives divulge their strategy of crowd-sourcing to find another Monopoly-tier hit: people from around the country would send their ideas with hopes that it would strike a fancy with the gatekeepers of fun.

“The inventors of successful board games are invariably amateurs, and not one has ever struck it rich more than once,” Parker Brothers disclosed. No one person was ever certain of what would become a hit, and the company relied on numerous test groups of various demographics. There were some gaming no-nos though, like witches and — early on — dice.

Pete Martin’s 1945 profile on Parker Brothers, which was located in Salem, Massachusetts, tells that “The game of Witchcraft was dropped when the embarrassed descendants of those New Englanders who took part in the seventeenth-century witch hunt asked that it be discontinued,” and, “Even as late as twenty years ago there were numerous parents who held that dice were instruments of the devil.” It is safe to say that Dungeons & Dragons would have been rejected vehemently.

Many newer board games laugh in the face of Parker Brothers’ old unwritten rules of what makes one popular: “A successful game should be simple, shouldn’t take too long to play, and even children should find it easy to learn.” In defiance of this advice, a 2016 cooperative game called Gloomhaven features a 52-page encyclopedia of a rule book whose contents are as foreign as a specialized medical textbook to those not in the know: “Monster statistic cards give easy access to the base statistics of a given monster type for both its normal and elite variants. A monster’s base statistics will vary depending on the scenario level.”

Still, for want of less time in front of screens or for lack of cash for extravagant entertainment, people keep playing games. Maybe it isn’t a consequence of anything other than the unbridled joy that they bring. One gamer wrote to Parker Brothers around 1966, “My cousin got married and went to Germany for her honeymoon, and she said they played Monopoly every night for enjoyment.” For some, the pastime has always been more than a necessity on a rainy day.

Check out the hidden history of Monopoly in the Post’s recent article, “Who Really Invented Monopoly?”

Who Really Invented Monopoly?

For decades, the story of Monopoly’s invention was a warm, inspiring, Horatio Alger narrative. A version of it, tucked into countless game boxes, told the tale of an unemployed man, Charles Darrow, who went to his Great Depression-era basement desperate for money to support his family. Tinkering around, he created a board game to remind them of better times, and finding modest success selling it near his home in Philadelphia, Darrow eventually sold it to the American toy and game manufacturer Parker Brothers. The game, Monopoly, became a smash hit, saving both Darrow and Parker Brothers from the brink of destruction.

The creation story is laced with persistence, creative brilliance, and an almost patriotic presentation of work ethic.

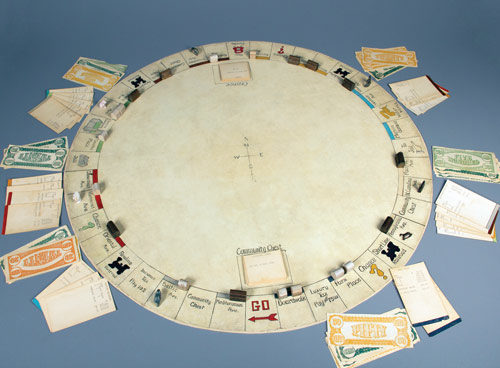

The problem is — it isn’t exactly true. What’s more, Monopoly’s origin story teaches us that innovation can be a complicated affair and that the “light bulb” moment of how things get made is, in fact, sometimes a myth. (The scale of Thomas Edison’s own contributions to the invention so associated with his name, fittingly, is now debated.) In the case of Monopoly, the journey of American invention was less a linear path and more a messy room shared by several people. The game was, in fact, created in 1903 — long before Darrow’s mythical basement revelation — by Elizabeth Magie, the daughter of an abolitionist who was herself a staunch anti-capitalist crusader. Magie created Landlord’s Game, the forerunner to Monopoly, not as a celebration of wealth but as a protest against the evil monopolies of the time.

Three decades before Parker Brothers and Darrow took credit for it, her game was embraced by a constellation of notable left-wing Americans of the time, as well as on various college campuses in the Northeast. ACLU chairman Ernest Angell played it, and so did Scott Nearing, a radical professor at Wharton, champion of academic freedom, and a father of the “green” movement. It flourished in Arden, Delaware, a tiny utopian village founded by followers of popular political economist Henry George’s “single tax” theory, a belief system Magie was passionate about. Among the residents of Arden who embraced the game was Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle, who corresponded with, and possibly met, Magie.

In the 1920s, homemade copies of Magie’s game found their way to what was then a flourishing Quaker community in Atlantic City. Quaker teachers in Atlantic City incorporated it into their teaching — with some modifications. Dice, associated with gambling, were discordant with their religious beliefs. The Quakers, practitioners of silence, also did away with the loud auctioning associated with the game, added fixed prices to the board, and modified it to be more child-friendly.

It was a version of this game — Magie’s Landlord’s Game with some of the Atlantic City Quaker modifications — that a friend taught Darrow to play. Darrow then sold it to Parker Brothers.

Darrow and Parker Brothers made millions for “creating” Monopoly, whereas Magie’s income from the game was reported to be a mere $500. She died in 1948, having outlived her husband, with no children and few knowing of her role as the true originator of the game that became Monopoly. She had worked in Washington, D.C., in relative obscurity as a secretary, and her income as a maker of games, according to the 1940 U.S. Census, was “0.”

Magie’s story would have been lost if not for Ralph Anspach, an economics professor at San Francisco State University whose legal battle over his own Anti-Monopoly board game in the 1970s unearthed the whole scandal. Anspach, today in his 90s and retired from teaching, but still selling his game, became a tireless detective of Monopoly’s origin story and spent a decade fighting for the right to talk freely about what he’d discovered. Although Magie and Anspach never met — Anspach was a child refugee of Danzig at the time Magie was close to dying — their fates became linked together unexpectedly. Anspach’s fate partially hinged on proving Magie was the inventor; Magie’s story would not have been told without a digger and advocate like him.

Over the five years it took me to research The Monopolists and in the two years since its publication, I’ve seen many a jaw drop as I told the tale of Monopoly’s lost inventor and her unlikely exhumation. The most common question is, “How did this happen?”

In Magie’s time, it was far too easy to suppress the voices of marginalized groups, including women. At the time she patented her game, she didn’t have the right to vote. The head of the U.S. Patent Office was actively discouraging women from applying for patents. Job opportunities were extremely limited, and it was common in the press to talk about how “weak,” “delicate,” and “smaller-brained” women were.

The greater astonishment maybe isn’t just that Magie lived the life of a game designer and political thinker far before her time, but that any shreds of her story survived at all. In my research, I stitched together enough of Magie’s trail — newspaper articles, Census records, her own writings, photographs — to get a sense of who Magie was and what she was trying to say to the world. But it’s hard not to think of her peers in her time who left far less behind, including female branches of my own family tree. Their contributions were large, but often silent, an untold quantity of labor that helped build this country. History is full of Lizzie Magies, Quaker teachers, friends who share ideas, the kinds of people who help shape our world and go largely unnoticed for doing so.

Courtesy of The Strong National Museum of Play, Rochester, New York.

The “light bulb” idea and the Darrow myth persist, in part because we want them to. On some level, we all fantasize about a lightning bolt of brilliance hitting us. The instantaneous nature of that seems particularly American: fast food, fast cars, fast road to becoming an innovative — and wealthy — genius.

Part of the reason today’s incarnation of Monopoly is so fun to play is that it was tweaked from Magie’s original design for better play. The core of the game is Magie’s, but the Atlantic City properties, the fixed prices, and the graphics all helped make it better. In today’s era of selfies, being one’s own publicist on social media, and the egotism wrapped around one’s Twitter follower count, perhaps Monopoly’s creation story reminds us that, together and connected, we are better. The “light bulb” narrative of invention, by definition, largely omits much chance for collaboration, a force that can be as vital for creation as the air we breathe.

Perhaps it’s always been more than a game after all.

Mary Pilon is the author of The Monopolists, a New York Times bestseller about the history of the board game Monopoly. This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square. The essay originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the September/October 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

For more on board games, check out “A New Wave of Board Games is Breaking Parker Brothers’ Rules.”