Second Chapters: An Octogenarian in the Peace Corps

The difference between a career and a calling, according to John Guy LaPlante, is that a career occupies your time until you retire. It can be satisfactory and pleasant, but after you retire, you never do it again and you never think about it again. “When you have a calling, you do it until your last breath,” LaPlante says.

John’s calling is effecting change for the better, and he continues to strive for a better world as his 88th birthday approaches. When John was 77, he felt a calling to join the Peace Corps.

It began when John saw a concert given by a Coast Guard Academy band. After seeing so many servicemen in the audience, he felt bad having never served in the armed forces. Afterward, John said he read an article about a Peace Corps initiative to recruit senior volunteers for their wisdom, experience, and desire to give back. He met with a recruiter in Los Angeles, and — after telling his family about his somewhat zany plan — he started the yearlong process of completing the necessary paperwork and medical exams.

John speaks with a thick New England accent from spending most of his life in Massachusetts and Connecticut, but his first language was French, taught to him by his Québécois parents. John figured the Peace Corps would send him to a country where his bilingualism would be valuable — Haiti, Vietnam, maybe Northern Africa. These locations also suited his aversion to the cold; John was escaping to Southern California each winter to avoid Connecticut’s harsh weather.

He was surprised to learn he was being sent to Ukraine and needed to learn Russian. John attended daily Russian classes, and he even began waking at 4 a.m. to study before his lessons. “I was the worst Russian student the Peace Corps has ever had,” he said. “I would study at night and forget the words in the morning because I was so damn old.” He was admitted to the program nonetheless.

Just 50 miles east of Chernobyl lies Chernihiv, Ukraine, where John was assigned to teach English at a state language school. Chernihiv was no Newport Beach; the winter chill was cruel and the living standards dissimilar. He was perturbed by a young boy in his first host family who seemed to suffer a disability that rendered him unable to attend school. John connected with him and lamented that his situation was not a rare one. John was stirred to improve the lives of Chernihiv’s citizenry in any way he could.

John became a regular at the local Korolenko Library. After sensing the enthusiasm of his English students at the school, he took it upon himself to lead an English Club — soon followed by a French Club — at the library on Sunday evenings. He tutored young people one-on-one and became invested in a mission to foster their interest in reading. This proved difficult, however, in a library with no digital catalogue of its contents.

Each Peace Corps volunteer is responsible for creating and leading a project of some significance apart from their service responsibilities, and it was at the library that John got an idea for his personal project: He developed a system to digitally organize the materials of the multi-building library campus. His ambitious plan was met with some resistance by nervous librarians who feared losing their positions to such a database, but John assured them their jobs were safe.

If reorganizing the library’s database wasn’t enough, John also noticed that the complicated, multi-tiered system of buses, trains, and trolleys lacked an inclusive guide, so he made it his mission to develop one. He worked with the municipality to establish a self-sustaining directory with keys, schedules, and a visual map that still exists today in print and online.

John’s successes in the program were considerable, but he noted — usually with the phrase “jeepers creepers!” — that he experienced hardships and setbacks as well.

One winter night, as he walked to a marshrutka (small bus) station in Chernihiv, LaPlante was inadvertently caught up in a drunken couple’s argument over their last bottle of beer, and he was knocked off the sidewalk and into the road. As he lay there, dazed, a police car pulled up and the Chernihiv Militsiya approached him. “They thought I was drunk!” he said. “Probably because of my terrible Russian.” It was imperative for John to convince the officers of his sobriety since excessive drinking can be cause for disciplinary action in the Peace Corps. Only after he could produce the necessary paperwork did they believe his story and offer him a ride home.

In another instance, John’s passion for teaching his students landed him in the Dean’s office when he went off-book for his lessons. He devised exercises to teach his students American English when he felt the required textbook’s British English was inappropriate. “I thought I was doing a superior job!” he offered. His supervisor, however, urged him to follow the text more closely.

Despite his troublemaker tendencies and atrocious Russian, LaPlante was never ousted from the program as he feared he would be. In fact, he received a call from the director of Peace Corps, who informed him that, at 80 years old, he was currently the oldest Peace Corps volunteer in the world. “I asked what had happened to my predecessor,” John said, “and she said, ‘Oh, that guy had to be medically evacuated.’”

As John’s Peace Corps service neared its end, he wished to leave a final, lasting impression on the program that would rouse unity and morale in its members: an anthem. John recalled the galvanizing tunes of the military service branches that stirred in him a desire to be involved in such an institution, and he envisioned a similar song for the Peace Corps. Despite his efforts to coordinate lyricists and composers — including a plan for a selection jury — John’s call for an anthem fell on deaf ears at the Peace Corps. “They just couldn’t understand the beauty of it,” he said.

John still sings the praises of the Peace Corps, if not literally. In 2011, adding to his other travel books, he self-published 27 Months in the Peace Corps: My Story, Unvarnished, a book about his experiences as a Peace Corps volunteer.

When John speaks with others about his experience, people often tell him they contemplate serving, and he always responds, “It’s not too late.”

John blogs about his life and travels on his website, www.johnguylaplante.com.

Rethinking Kennedy’s Camelot

This is the third installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

In the years following the death of President Kennedy, many people often spoke of his presidency as an idyllic time. Picking up on Jackie Kennedy’s reference to the Richard Burton-Julie Andrews musical, they dubbed those pre-assassination days as “Camelot,” a noble, idyllic but ultimately doomed kingdom.

It is easy to imagine such a bright, innocent time existed on the far side of the tragedy. But was the country truly different before Kennedy’s assassination?

Excerpts from several Post articles in 1963, prior to the president’s death, demonstrate that in truth America was already in the midst of troubling times that little resembled the idyllic innocence of “Camelot.”

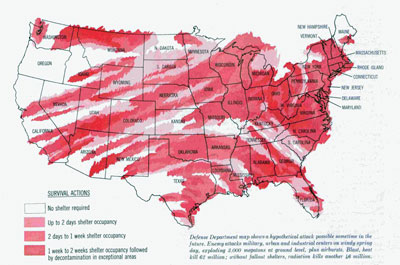

In March of 1963, the Post ran “Survival of the Fewest,” which informed readers that the U.S. could not protect them from a possible nuclear attack. Government strategists had calculated that nuclear weapons from a Russian attack would directly kill 21 million Americans. Radioactive fallout would kill an additional 13 million, they estimated, unless citizens had access to bomb shelters.

At the time of the article, the Kennedy administration had already called on the nation to construct enough fallout-shelter space for 240 million Americans over a five-year span, yet few Americans took action to protect themselves from nuclear holocaust. Only a small fraction of the necessary fallout shelters were built, because homeowners found them expensive, inefficient, and hard to assemble. Radio stations continued to regularly test their connections with the CONELRAD civil defense system, and school children still huddled under their desks when the town siren was tested, but by 1964, demand had disappeared and one California dealer couldn’t even give the shelters away.

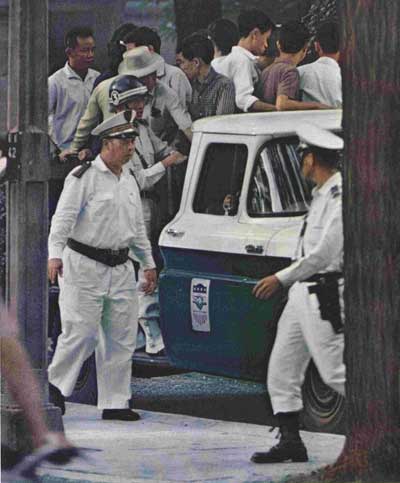

At the same time that Americans worried about Russia’s nuclear arsenal, they learned that the U.S. was getting pulled into yet another distant confrontation with Communism. In September of 1963, the Post reported in “The Edge of Chaos” that, “President Kennedy, convinced that a Communist takeover of South Vietnam might mean the fall of Southeast Asia, has repeatedly promised to defeat the guerillas that dominate much of the country. He has backed up his words with a 16,000-man U.S. force in Vietnam—more than 100 have lost their lives—and with $1.5 million a day spent on the war.”

© Curtis Publishing Co.

“But,” the article continued, “the spectacle of American-trained troops using American weapons to raid Buddhist temples made clear one fact that U.S. officials have long tried to evade: No matter how much the United States supports the unpopular regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, this regime’s chances of victory over the Communists are just about nil.”

Ever since World War II, the country had been opposing communist expansion, first in Eastern Europe, and then in Central America, Africa, and Asia. Its principal weapons in this fight were money, arms, and military supporters. But by the 1960S a new element had been added to the Cold War, instigated partly by a novel that had been serialized in the Post.

In 1958, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer wrote The Ugly American out of their anger at seeing American prestige dissolving in Southeast Asia. They were outraged by the way American diplomats and advisors were “ doing the wrong thing, or doing the right thing the wrong way, or just doing nothing.”

Serialized in five parts from October 4, 1958 to November 8, 1958, their novel about a fictional diplomat in Asia drew a generally negative response from government officials. The State Department dismissed the book as a “distortion,” and it was criticized by President Eisenhower and several senators. But after Senator John Kennedy read the book, he bought copies for the entire senate, and the government began to respond.

In “The Ugly American Revisited,” [June 4, 1963], Burdick and Lederer reported, “American foreign aid is now a much more practical, tough-minded proposition than it was five years ago.”

In their article, the authors also admitted they’d been stunned by the public response to their book, which had sold nearly 4 million copies. Even more startling were the thousands of letters from individual Americans asking, “What can I do?” To the authors, this response reflected a deep concern among Americans about their position in the world. “They are often confused, often angry, but always willing to learn. They possess a quiet awareness of the deadly peril in which we live. And they are, more important, ready to ‘do something about it.’”

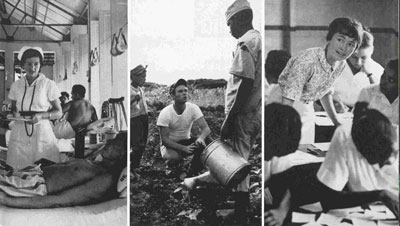

What many of them did about it, wrote Burdick and Lederer, was volunteer for the Peace Corps, which Kennedy had founded as one of his first acts, in 1961, and which had been a resounding success. “Indeed, it is quite without parallel in history,” they wrote two years later. “It is a source of great pride to us that a majority of Peace Corps volunteers indicated that their first interest in foreign affairs came from reading ‘The Ugly American.’”

Burdick and Lederer saw a new mood spreading through the country. “Americans, in both high and low places, are willing to be critical of themselves without falling into despair. On balance, America is surely moving with greater energy, more skill and more confidence in its overseas operations.”

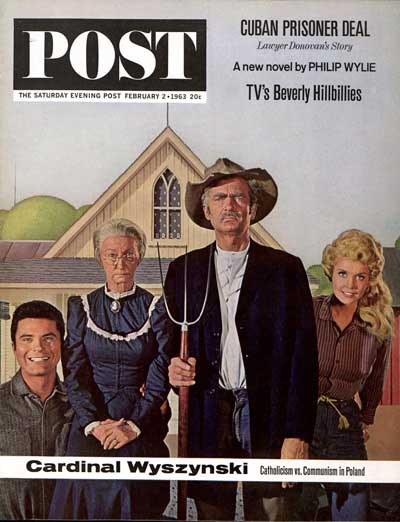

But the America of 50 years ago could also be characterized by its entertainment, some of which did not especially resonate with the nobility of the knights of the round table. The most popular television show, The Beverly Hillbillies, was a prime target for reviewers’ abuse (the Post declared it was “deliberately concocted for mass tastelessness.”)

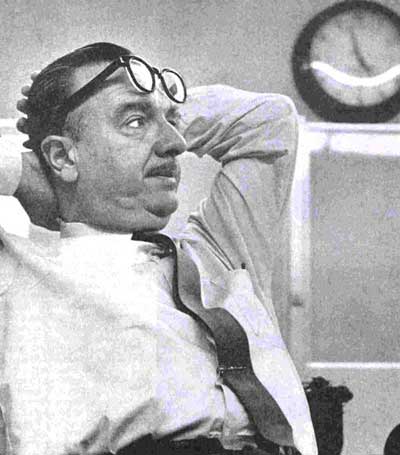

But television in 1963 also had the sedate and reliable Walter Cronkite, whom the Post profiled in March of that year. Cronkite was still relatively young, just a few months older than President Kennedy. But he, too, was a veteran, having reported World War II from a B-17 and with the 101st Airborne division.

“He has conversed with queens and dictators,” wrote Post author Lewis Lapham, “lived under the polar ice for a week, seen governments fall and atomic bombs exploded.”

And he was now the trusted anchorman of the CBS evening news, a post he was to hold for another 18 years.

In that distant time, before Americans preferred their news heavily seasoned with entertainment, Cronkite won the loyalty of viewers with his fairness and adherence to facts.

“Cronkite’s detractors usually criticize him for this unwillingness to advance an outspoken opinion. They complain that he is too polite, too bland, too dull,” wrote Lapham. “He considers the criticism unreasonable. ‘Probably if I made a few more acerbic remarks, I might win a few more viewers,’ he concedes, ‘but I don’t feel like being funny with the news; I don’t think that’s my place.’”

Just a few months after Lapham’s article was published, Cronkite became part of the permanent memories of a generation of Americans when he delivered the news of President Kennedy’s assassination.

“If, in the search of our conscience we find a new dedication to the American concepts that brook no political, sectional, religious or racial divisions,” Cronkite observed following Kennedy’s funeral, “then maybe it may yet be possible to say that John Fitzgerald Kennedy did not die in vain.”

To read more from the Post‘s series on John F. Kennedy, click here.

The Deathless Legacy Of Sargent Shriver

Sargent Shriver’s health failed him before he could celebrate the Peace Corps’ 50th birthday this March. He died January 18th, at the impressive age of 96. Given a choice, he probably would not have wanted a eulogy as much as promotion for the cause so close to his heart.

So we quote today from a Post article —“The Peace Corps: Making Friends for America.” Even in 1982, with the country’s culture wars just starting to heat up, the program enjoyed broad (we could even use the word “bipartisan”) support among public figures.

There are President Reagan and [recently appointed Peace Corps] Director Loret Miller Ruppe. Then, John F. Kennedy. “Miss Lillian” Carter. Bill Moyers. The King of Tonga. Senator Paul Tsongas. Father Hesburgh. Sargent Shriver. Unlikely allies, but all linked through one strong common interest.

Shriver was the founding director of the Corps—which began in 1961—and served under his liberal Democrat brother-in-law. President Kennedy, who originally proposed the organization in his campaign promises. Ruppe, President Reagan’s Peace Corps head, is—like her chief—a conservative Republican. Yet both directors testify to the enthusiastic backing of their chief executives, 20 years and political poles apart. Both directors won their White House standing through vigorous and successful election campaigning.

Today, Ruppe… is confident that the Peace Corps is on the threshold of a new era of growth and public recognition, fully in harmony with President Reagan’s philosophy of expanding the private-sector role in serving the public good. But it isn’t easy, especially since the Peace Corps has had such a low profile in recent years that many people, even in government-centered Washington, assume that it was one of those “nice ideas” that was abandoned long ago.

Over the past two decades, the Peace Corps has enlisted and sent out to 90 countries more than 85,000 volunteers.

Today, those numbers have grown 139 countries, and the total number of volunteers is nearly 250,000,000.

Wherever former Peace Corps volunteers live and work, they are symbols of caring concern, inclined to be active in community service and, inevitably, bridges between their hometown neighbors and visitors and immigrants from abroad. Some outside observers— and many of the volunteers themselves —believe that one of the main achievements of the Peace Corps has been the expanded and enriched education, experience and global understanding it has provided for those who have had PC assignments abroad.

However true that may be, the chief purpose of the Peace Corps today, as in the past, is to help other people in the poorer, less developed countries help themselves.

When the conservative government of Ronald Reagan arrived in Washington, there was a widespread belief that foreign aid would be drastically slashed, if not abolished. It didn’t quite happen that way. Despite initial proposals by the Office of Management and Budget for cutting the A.I.D. budget in half, and reducing the Peace Corps funding by about one- fourth, bipartisan support for maintaining a substantial assistance program won out. The Peace Corps allocation was held to $105 million. This represents, in actual value of the dollar, only about half the $114 million available to the Corps in 1966, when it had some 15,000 volunteers on duty in more than 70 countries.

In 2010 dollars, that 1966 budget would be about $700 million. In actual 2010 dollars, though, the budget for the Peace Corps is now $400 million.

Loret Ruppe sees the entire Peace Corps operation as a prudent national investment of long-term benefit to the countries being helped, to the interests of the United States and to the peace of the world. She is thoroughly opposed… to a hand-out approach to solving people’s problems at home or abroad. But the Peace Corps, she points out, is one of those down-to-earth endeavors in which the emphasis is on helping people to help themselves—and it has a track record to prove that such an approach really works.

In a speech at the Peace Corps’ 35th anniversary, in 1996, Ruppe recalled the moment President Reagan changed his attitude toward the program.

In 1983, I was invited to the White House for the state visit of Prime Minister Ratu Mara of Fiji. Everyone took their seats around this enormous table—President Reagan, Vice President Bush, Caspar Weinberger, the rest of the Cabinet, with the Prime Minister and his delegation, and myself.

They talked about world conditions, sugar quotas, nuclear free zones. The President then asked the Prime Minister to make his presentation. A very distinguished gentleman, he drew himself up and said, “President Reagan, I bring you today the sincere thanks of my government and my people.” Everyone held his breath and there was total silence. “For the men and women of the Peace Corps who go out into our villages, who live with our people.” He went on and on. I beamed. Vice President Bush leaned over afterwards and whispered, “What did you pay that man to say that?”

A week later, the Office of Management and Budget presented the budget to President Reagan with a cut for the Peace Corps. President Reagan said, “Don’t cut the Peace Corps. It’s the only thing I got thanked for last week at the State Dinner.” The Peace Corps budget went up. Vice President Bush asked kiddingly again, “What did you pay?”

Well, we know one thing: It isn’t for pay that Volunteers give their blood, their sacred honor. I can never forget those who died while I was Director. Let us never forget those who have given their lives or were disabled in service. I can never forget the sweat, the tears, the frustrations, the best efforts, and successes of thousands of Peace Corps Volunteers. I stand in awe and with the deepest respect.