5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

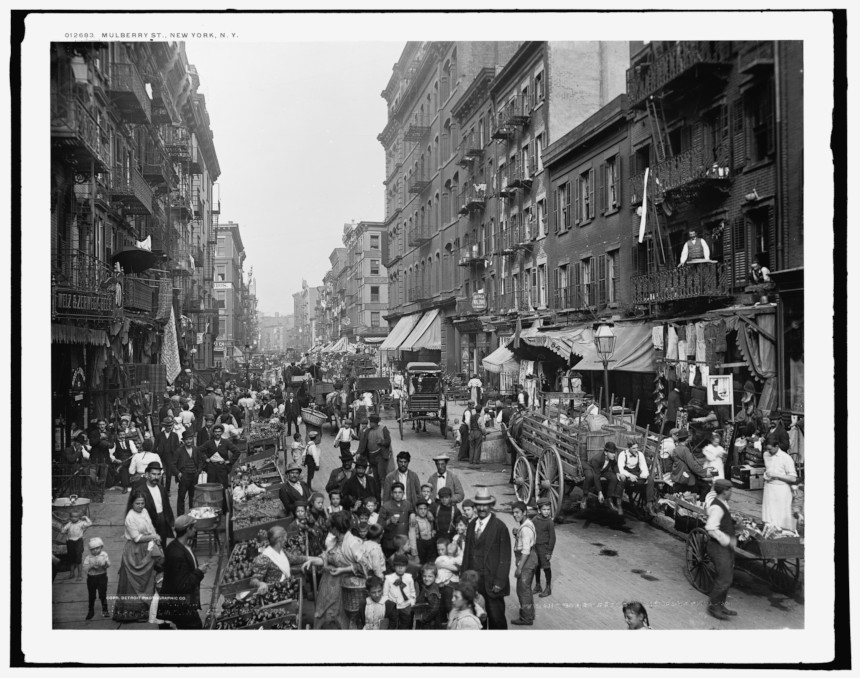

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

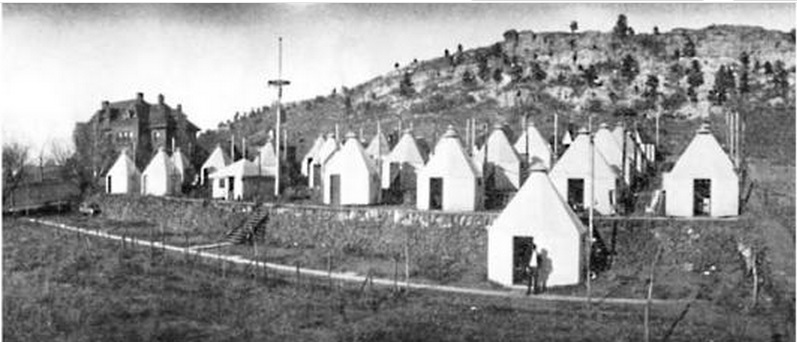

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

The Post Reports on Vaccines

Recent measles outbreaks have brought renewed media attention to and public discussion over vaccination. While the scientific community supports vaccination, some parents have rejected vaccinations for their children.

Yet vaccination has been a part of healthcare since the early 1800s, and The Saturday Evening Post has been reporting on them since the inception of the magazine.

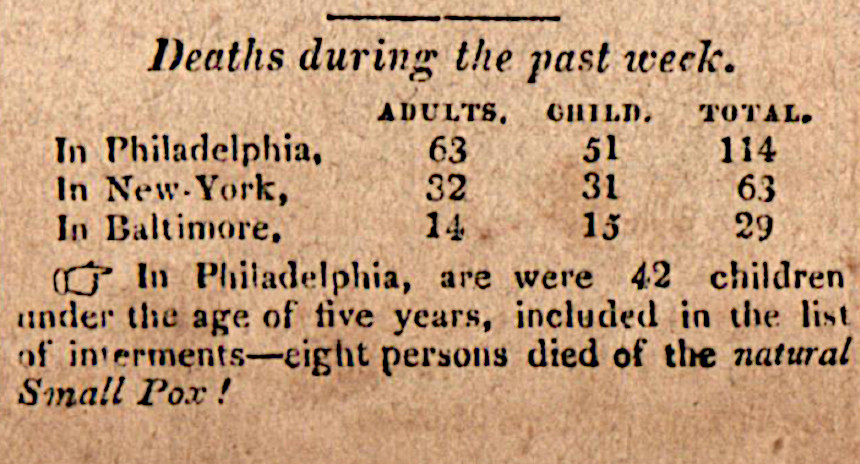

The first Post mention of a vaccine was April 27, 1822, where the magazine noted the repeal of the Vaccine Act of 1813, the first federal law over consumer protection and pharmaceuticals. The act encouraged public vaccination against smallpox but was repealed in order to give the power of regulation to the states, where it has remained since.

A year later, in the November 29, 1823, issue, in a line item warned: “Small pox, it is feared, will prove fatal to many persons in Yarborough, N.C. owing to the use of matter not genuine, which had been forwarded to Dr. Ward by Dr. Smith, the United States’ Agent for vaccination.”

Concerns about the smallpox vaccine’s purity, efficacy, and authenticity persisted. People feared the vaccine would produce a “harmful disease” or “other diseases than vaccinia,” or “that compulsory vaccination is a trespass upon the inherent rights of the individual.” The earliest vaccine protesters believed that “the reduction in smallpox mortality in civilized countries to the generally improved sanitary conditions.” They did not associate lower rates of disease with higher vaccination levels as we do today.

Despite concerns, the smallpox vaccination grew widely. In the early 1800s, the vaccination was mandatory for infants in certain states, but deaths still occurred.

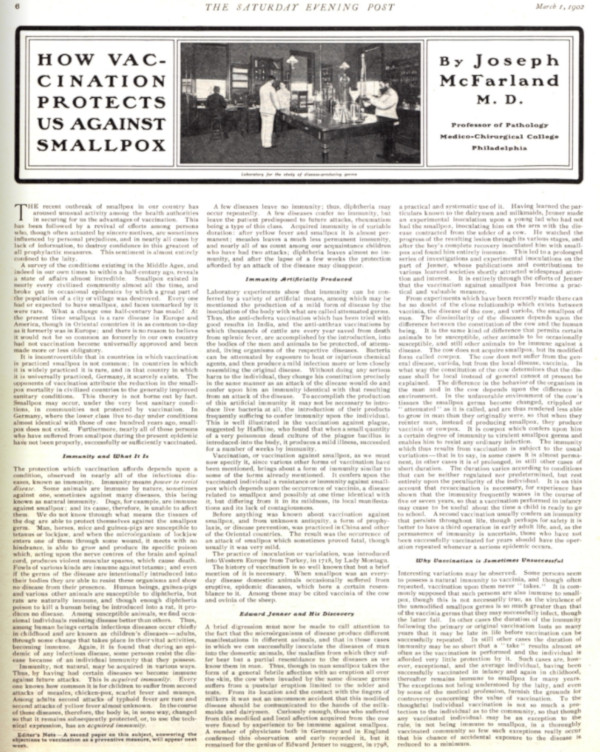

On March 1, 1902, an article titled How Vaccination Protects Us Against Small Pox, written by Joseph McFarland M.D., claimed “To the thoughtful individual vaccination is not so much a protection to the individual as to the community.” Due to their ability to prevent smallpox, the doctor believed the vaccine to be the “greatest of all prophylactic measures” and a great aid to American well-being.

As the years passed, protesters of the smallpox vaccine diminished along with the disease it prevented. Americans put their faith in inoculation and spread the process to other countries. When discussing vaccinating infants against smallpox, typhoid, and diphtheria in a May 16, 1936, article titled The New Machine, the magazine claimed “It may seem to many people that it is cruelty or dangerous to subject a little, delicate organism to the onslaught of these vaccines, but it is far more dangerous to let them go without it.”

Then there was the story of polio.

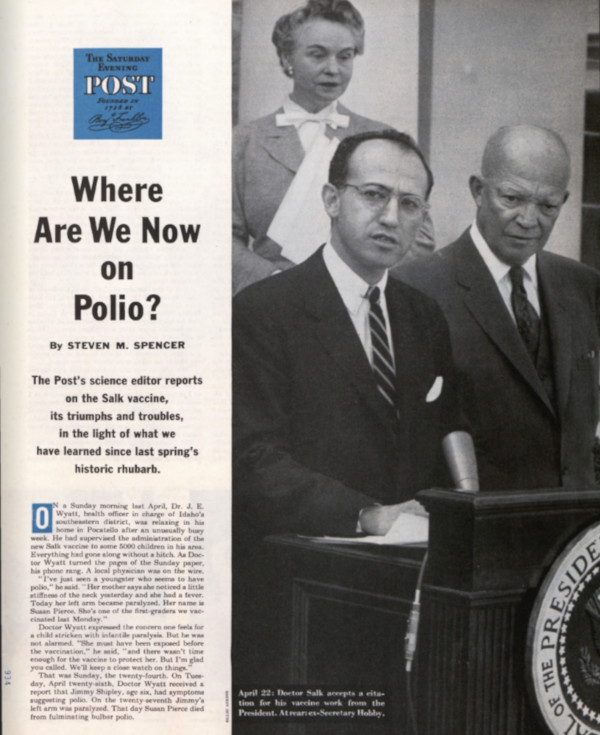

In April of 1955, Dr. Jonas Salk accepted a citation for his vaccine work from President Eisenhower. The new polio vaccine was a beacon of hope in fighting a deadly and terrifying illness. Polio cases in the U.S. fell from 35,000 in 1953 to 5,600 just four years later. In 1955, more than 8 million children had received the vaccine. By 1961, there were only 161 cases.

But the rollout of the vaccine was not without its problems. In the spring of 1955, several children contracted polio a week after receiving the vaccine, and some died. A panel of experts was convened in Washington, where they issued conflicting advice. Some wanted to temporarily halt the program. Others urged that it should move forward. Worried parents didn’t know what to do, and vaccination rates dropped.

Basil O’Connor, the president of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, was eager to see the program continue. He had seen too many children paralyzed or killed by the disease. At the hearing in Washington, he pointed out, “Since the scientific method was established, every important advance in science has met with the twin obstacles —ignorance and envy.”

But no one intended to do away with the polio vaccine. Research efforts continued, and a safer version the vaccine was developed in 1961. Polio was completely eliminated in the U.S. in 1979.

Throughout the century the vaccine saved thousands of lives and prevented countless outbreaks. By 1964 scientists were even wondering if they could vaccinate against cancer.

So why do concerns about vaccinations persist?

After the eradication of small pox and polio and the subsequent reduction of measles, a generation of parents who had never experienced these diseases began to question why their children should be vaccinated.

A now discredited study released in 1998 claimed relationship between vaccines and autism, quickly becoming a topic of great discussion in the United States. The journal retracted the study, but it was too late. Goaded by internet forums and a few strident celebrities, many concerned parents took a stance against vaccination.

Theirs was a movement that had existed in some part since the advent of vaccines. Vigorous protests have led to exemptions to the required vaccinations. While all state laws have “no shots no school” policies that prevent unvaccinated children from attending public schools, there are various exemption practices by state. All states allow medical exemptions for children to whom the vaccine could be harmful, and all but six states (California, Minnesota, Mississippi, West Virginia, New York, and Maine as of June, 2019) allow exemptions on religious grounds. Many states have also included a philosophical exemption for parents who protest vaccination for non-religious reasons. All exemptions can be revoked “during a public health emergency or outbreak of a communicable disease,” such as the recent measles outbreak.

Despite regularly making headlines, the anti-vaccination contingent remains in the far minority of the population. A CDC report published in 2018 revealed that the median percentage of kindergarteners with an exemption from one or more required vaccination was 2.2 percent. The “median percentage of nonmedical exemptions” was 2 percent. Most Americans support vaccination and the preventative power it holds. The vaccine’s long history in this country has saved countless lives and has turned public perception from doubtful to hopeful.

Featured image: At a McLean, VA, school, nurses Lillian Peyton and Mrs. John Lucas help Dr. Richard Mulvaney give Barbara Ann Schmitt a Salk polio vaccination (Photo by Ollie Atkins for the September 11, 1954, issue of The Saturday Evening Post)

The War on Polio

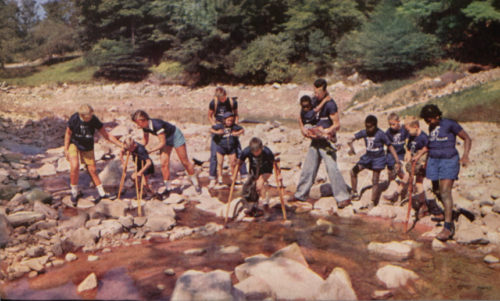

To the 4-year-old Ethiopian girl standing barefoot in the doorway of a thatched mud hut, the burly white guy beckoning to her from his wheelchair must have cut a curious figure. With eyes wide and lips slightly parted, she stepped toward him and opened her mouth as if to receive communion. And Steve Crane, 6-foot-4 and 250 pounds, held out his hand, and the blessing he gave her was in the form of a vial containing drops of oral polio vaccine.

Crane had come from Seattle to Yirgalem and Awassa, villages in southern Ethiopia, to save children’s lives, or at least to spare them from the disease that had so fundamentally altered the course of his. “I contracted polio when I was 13 years old. It was 1955, just a few months after the Salk vaccine came out,” said Crane, who added, “Ethiopia isn’t real wheelchair friendly. Rotarians had to pick me up to get over cracks in the dirt alleys, and haul me up and down stairs when we went to meetings in Addis Ababa. But it was a privilege to prevent someone else from going through what I did.” Crane was part of a group from Rotary International, whose members have been traveling, usually at their own expense, as part of the global network’s main humanitarian cause: polio eradication. Along with the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), UNICEF, and in recent years the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, it makes up the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), which has run immunization campaigns for almost 30 years.

Today, thanks to this global effort and the huge organization built to support it, the end of polio is within sight. As of November 25, 2014, there were only 306 cases. Compare that to 1988 when 350,000 people fell victim to the disease worldwide. The enormity of the achievement is hard to overstate. Some compare it to the effort to land a man on the moon. But the international infrastructure built to defeat polio — a unique collaboration in today’s fractured world — has provided the blueprint for addressing other global scourges, including malaria, measles, and, yes, Ebola too. “We now have the infrastructure,” says Oliver Rosenbauer, a spokesman for WHO in Geneva. “We have staff. We have the transportation means, the administration, the data, and the social mobilization network of local workers. That infrastructure has always been used to respond to other emergencies. Whether it’s a drought or a tsunami or the earthquakes in Pakistan, the polio teams were pulled in to help with the emergency response. The same thing is happening with Ebola. The staff in West Africa are helping, doing contact tracing, helping with surveillance, helping with social mobilization — all of that is happening in these countries and neighboring ones has well.”

Wild poliomyelitis is caused by a highly contagious virus that usually spreads through feces and enters victims through the mouth. It attacks the spinal cord and brain stem, and paralyzes arms, legs, and muscles that control breathing, swallowing, and speech. What encouraged people to think it was eradicable is that like smallpox, which was vanquished in 1979 after a 12-year campaign, people are the only reservoir in which polio can survive.

Based on Egyptian steles depicting the telltale drop foot, we know the disease has been around for at least 35 centuries. Even so, it was only in the late 18th century that polio became a full-blown global epidemic. Paradoxically, it was an unexpected consequence of vastly improved hygiene and sanitation, especially clean water and sewage removal systems in cities. When people lived in harsher conditions, they were more commonly exposed to the virus and built up immunity to it.  (Most people who get polio never know it, experiencing symptoms as mild as a touch of flu, drowsiness or a sore throat. Paralysis is quite rare, hitting one in 200 people who get the disease.) But as the world became more populated, when the virus did show up, it had a larger group to infect. In 1952, a global outbreak peaked with 600,000 cases. Photos show wards of people, unable to breathe on their own, encased in gruesome-looking iron lungs. Three years later, Jonas Salk’s injectable inactive polio vaccine (IPV) became available for public use. In 1957, another American, Albert Sabin, developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) that contained a live, though weakened, form of the disease. And it had practical advantages: It was cheap and didn’t require any expertise to administer, so was relatively easy to deliver. Children in wealthier nations were inoculated. The last case in the U.S. was 1979 and in Britain 1985.

(Most people who get polio never know it, experiencing symptoms as mild as a touch of flu, drowsiness or a sore throat. Paralysis is quite rare, hitting one in 200 people who get the disease.) But as the world became more populated, when the virus did show up, it had a larger group to infect. In 1952, a global outbreak peaked with 600,000 cases. Photos show wards of people, unable to breathe on their own, encased in gruesome-looking iron lungs. Three years later, Jonas Salk’s injectable inactive polio vaccine (IPV) became available for public use. In 1957, another American, Albert Sabin, developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) that contained a live, though weakened, form of the disease. And it had practical advantages: It was cheap and didn’t require any expertise to administer, so was relatively easy to deliver. Children in wealthier nations were inoculated. The last case in the U.S. was 1979 and in Britain 1985.

For years polio was fought country by country with little international coordination. In 1988 the GPEI was launched with the then-quixotic-sounding mission of stomping out the virus from the face of the earth. Thanks to the initiative, healthcare workers have since given more than 10 billion doses of vaccines to 2.5 billion children. Now, 27 years and $9 billion later, the effort is on the lip of finishing the job. In the process it has marshaled a massive coalition of governments, non-governmental agencies, philanthropic foundations, celebrities, and clerics. And it has built a meticulous infrastructure to roll the massive global program forward.

To attack polio, you need information about where the disease is, and where people are who need to be vaccinated. Stripping the concept down to its core, the process is simple: Get the vaccine from the lab to the people who need it. That’s what the GPEI has become so good at doing. When polio does appear anywhere in the world, teams are dispatched to interview families and collect samples. Then geneticists at the CDC use genome sequencing to trace the exact route the virus traveled from its source and attack it there. For example, Mideast cases that appeared in 2013 were found to originate in Pakistan; cases in the Horn of Africa came from Nigeria. Health workers in the field are equipped with GPS and detailed charts that amount to a local census, marking off every place where a child lives and has or has yet to be vaccinated. WHO estimates that as a result of the GPEI, 10 million cases have been averted and 1.5 million childhood deaths have been prevented.

For all the sophistication of the war on polio, there are battles still to be fought — some of them still being lost. In 2013, National Immunization Days had new urgency after Ethiopia, which hadn’t had a case of polio in five years, had an outbreak of nine new cases. Neighboring Somalia was the world’s worst hit with 194 children paralyzed. Kenya had another 14 cases. Nor was Africa the only flashpoint. Syria, where civil war reduced the estimated percentage of vaccinated children to 68 percent from a pre-conflict 91 percent, had an outbreak of 35 new cases. The virus also surfaced in Israeli sewage in numerous locations, prompting a mass vaccination campaign. Though no Israelis contracted polio, its mere presence raised fears of reinfection in Europe.

All this in a year when polio workers were actively targeted and murdered in Pakistan, one of the three countries left where the disease is still endemic (Afghanistan and Nigeria are the other two). Although no one claimed responsibility, suspicion fell on radical Islamists. To be clear, support for eradication has been mostly robust throughout the Muslim world. Saudi Arabia requires proof of vaccination for all pilgrims from polio stricken areas as a condition of making hajj, the journey to Mecca. The Islamic Development Bank has made financing available to Pakistan. Malaysia, Qatar, and Kuwait have helped with financing and technical assistance, while Abu Dhabi hosted a major summit in 2013. But extremists remain a source of consternation to the polio community. “I don’t think there’s any question that polio eradication is impacted by anti-government groups in places like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Nigeria,” says Carol Pandak, director of Rotary’s PolioPlus program. “They’ve made it difficult to access children.”

The Ebola outbreak, too, threatens to hinder polio eradication efforts, particularly in Africa where the risk of Ebola threatens to impede the movement of polio workers. In fact, the timing of the Ebola outbreak could hardly be more frustrating: With just six polio cases in 2014 as of this writing, Nigeria is closer than ever to eradication. Ebola could prove to be a major setback. “We might only have a limited window of opportunity to finish polio,” says WHO’s Rosenbauer, “If Ebola got into northern Nigeria it would complicate polio activities.” Despite setbacks, there have been triumphs. In January 2014, India, once considered the disease’s most intractable redoubt, marked 36 months without a new case, allowing WHO to certify the Southeast Asia region polio-free. Of the countries where polio still persists, as of November 25 Nigeria had only a half-dozen new cases in 2014 compared with 50 for roughly the same time period in 2013; Afghanistan had 21 cases, compared with nine in 2013; and Pakistan, where warlords in Waziristan cut off access to vaccine, was the real dark spot with 260 cases, compared with 64 in 2013.

The fear of failure is ever-present for the GPEI. “Until it’s completely eradicated, it can flare up again,” says Dr. John Sever, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and vice chairman of Rotary’s International PolioPlus Committee. “If this spreads into populations that are not well-immunized, it could cross borders and re-infect areas that are currently polio-free.” The worst setback — remembered as “the disaster” — occurred in 2003 after rumors spread that vaccination was a Western plot to sterilize Muslim children. That shut down the Nigeria campaign for 13 months and led to reinfection in 20 countries. More recent rumors had it that vaccinators were fronting for Western intelligence agencies — and it hardly helped that the doctor who led U.S. troops to Bin Laden had in fact set up a fake vaccination clinic.

As massive as the cost of eradication is, the price of failure is higher. An economic analysis in the journal Vaccine in 2010 determined that without total eradication, the disease would run up a bill as high as $50 billion by 2035 — a figure that dwarfs the projected 5-year budget of $5.5 billion the GPEI says it needs to complete the mission, including a post-eradication plan that runs through 2018. The money is not fully available:  “We have approximately $4.9 billion in funds and pledges against the $5.5 billion we need,” says Rotary’s Pandak. “Only $1.8 billion of the pledges have been operationalized. The challenge is to realize those commitments as soon as possible.”

“We have approximately $4.9 billion in funds and pledges against the $5.5 billion we need,” says Rotary’s Pandak. “Only $1.8 billion of the pledges have been operationalized. The challenge is to realize those commitments as soon as possible.”

The legacy of eradication, advocates say, is an infrastructure of people and systems that other health programs will inherit — and that brings us back to the Ebola crisis. The two diseases are radically different and require different interventions. But Ebola reinforces exactly why the weak links in the chain of global healthcare need to be strengthened, and the network and methods of the GPEI — personnel, disease surveillance, communications structure, social mobilization, emergency preparedness plans, and logistics including the physical delivery of medicine and supplies — may be the best model.

Polio helped build up the capacity of countries with poor health systems, including a global laboratory and a communications network. There are now tens of thousands of health workers trained in containment of infectious disease. As a result, not just Ebola, but measles, malaria, and dengue fever are in epidemiologists’ sights. The polio endeavor fostered a better understanding of how to move science from the lab to the people in the streets and villages.

Most people who have participated in the polio effort can recall a moment when they became wedded to the mission. Ann Lee Hussey got polio in 1955 and suffers post-polio syndrome, the severe and lasting after-effects that can strike decades later and be intensely painful and disabling. Despite that, Hussey has been on 25 campaigns in seven countries including Mali, Bangladesh, and Nigeria. “It’s very healing to give the drops,” says Hussey. “It’s where I get my strength from. When I think of the faces and the people I met, I want to go again. It’s what keeps me going.”