Reassessing Jimmy Carter

Although it is conventional wisdom that Jimmy Carter was a weak and hapless president, I believe that the single term served by the 39th president of the United States was one of the most consequential in modern history. Far from a failed presidency, he left behind concrete reforms and long-lasting benefits to the people of the United States as well as the international order.

Let me be clear: I am not nominating Jimmy Carter for a place on Mount Rushmore. He was not a great president, but he was a good and productive one. He delivered results, many of which were realized only after he left office. He was a man of almost unyielding principle. Yet his greatest virtue was at once his most serious fault — he took on intractable problems with comprehensive solutions while disregarding the political consequences. He could break before he would bend his principles or abandon his personal loyalties.

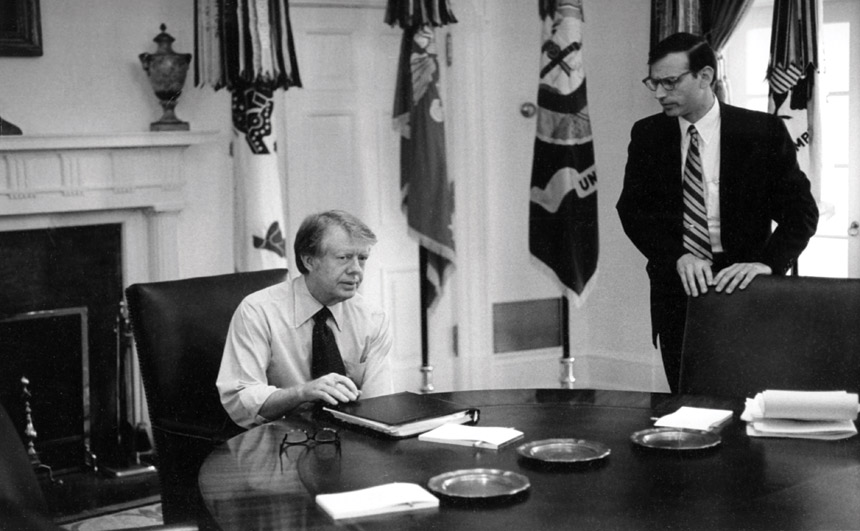

An extraordinarily gifted political campaigner, he nevertheless believed that politics stopped once he entered the Oval Office and that decisions should be made strictly on their merits. But to be truly effective, a president cannot make a sharp break between the politics of his campaign and the politics of governing if he wants to nurture an effective national coalition. This Carter not only failed to achieve — he did not want to. Time and again he would say, “Leave the politics to me,” while in fact he disdained politics.

Possibly as a result, critics disregard the breadth of Carter’s accomplishments and accuse him of being an indecisive president. That is simply not true; if anything, he was too bold and determined in attacking too many challenges that other presidents had side-stepped or ignored, such as energy, the Panama Canal, and the Middle East, while nevertheless achieving lasting results. The art of presidential compromise rests on the ability to obtain at least half of what the administration proposes to Congress and then to claim victory. President Carter was maladroit at this political sleight of hand largely because he was uncomfortable with compromising what seemed to him so obviously the right course.

One reason his substantial victories are discounted is that he sought such broad and sweeping measures that what he gained in return often looked paltry. Winning was often ugly: He dissipated the political capital that presidents must constantly nourish and replenish for the next battle. He was too unbending while simultaneously tackling too many important issues without clear priorities, venturing where other presidents felt blocked because of the very same political considerations that he dismissed as unworthy of any president. As he told me, “Whenever I felt an issue was important to the country and needed to be addressed, my inclination was to go ahead and do it.”

But even with Carter’s limitations, I refuse to let the mistakes overwhelm the achievements. We still benefit from his vision of the challenges faced by our country and the world, from his willingness to confront and deal directly with them regardless of the political cost, and finally from his essential integrity. He gained the presidency in a post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era of cynicism about government with a personal pledge that “I will never lie to you” — a promise that he worked hard to keep, and is now more important than ever in a new era of “fake news” and post-truth political rhetoric.

Public recognition of Carter’s legacy of accomplishments has been obscured by inexperience in the critical early stage of the administration; iconoclastic, idiosyncratic decision-making; double-digit inflation and interest rates; internal Democratic Party strife; and the Iran hostage crisis. But, like the successes of Truman, Clinton, and the senior Bush, Carter’s achievements shine brighter over time, few more than his unique determination to put human rights at the forefront of his foreign policy from the start of his presidency.

He gained the presidency in a post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era of cynicism about government with a personal pledge that “I will never lie to you.”

At the time, this shift from the realpolitik of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger was derided by some as utopian, and indeed some events demanded responses that did take precedence over human rights. But when backed by actions like cutting military aid to Latin American dictatorships such as Chile and Argentina, his human rights policies helped convert most of our Latin American neighbors from authoritarian rule to democracy.

The administration’s public advocacy of human rights also weakened the Soviet empire by attacking its soft underbelly — its domestic repression. No less than Anatoly Dobrynin, the long-time Soviet ambassador to Washington, conceded that Carter’s human rights policies “played a significant role in the … long and difficult process of liberalization inside the Soviet Union and the nations of Eastern Europe. This in turn caused the fundamental changes in all these countries and helped end the Cold War.”

As an Annapolis-trained submarine officer, Carter was no pacifist but was nevertheless very cautious — perhaps excessively so — about deploying American military power until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. No American soldiers were killed in combat on his watch. He signed the second and most ambitious Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) with the Soviet Union, which served as the basis for future arms limitation agreements. At the same time, he did not hesitate to support cutting-edge weapons technology.

Despite allied resistance, Carter persuaded European governments to begin deploying middle-range nuclear weapons in Europe to counter the Soviets’ new mobile missiles. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, later called this allied response a significant factor in convincing him that his predecessors’ policies of military threats to the West should be replaced by disarmament and accommodation.

In another bold step, taken over ferocious and emotional opposition from conservatives, his administration negotiated a treaty with Panama that yielded American sovereignty over the canal, avoiding an almost certain guerrilla war by Panama against this vital sea link, while fully protecting America’s priority use of the vital seaway. It led to a giant step in elevating U.S. relations with Latin America. And while Nixon and Kissinger deserve great credit for their dramatic outreach to the People’s Republic of China, they could go no further because of fierce opposition from the Taiwan lobby, a major force in the Republican Party. It fell to Carter to take the lasting step of normalizing diplomatic relations with the most populous nation in the world as it grew into a power that could not be ignored.

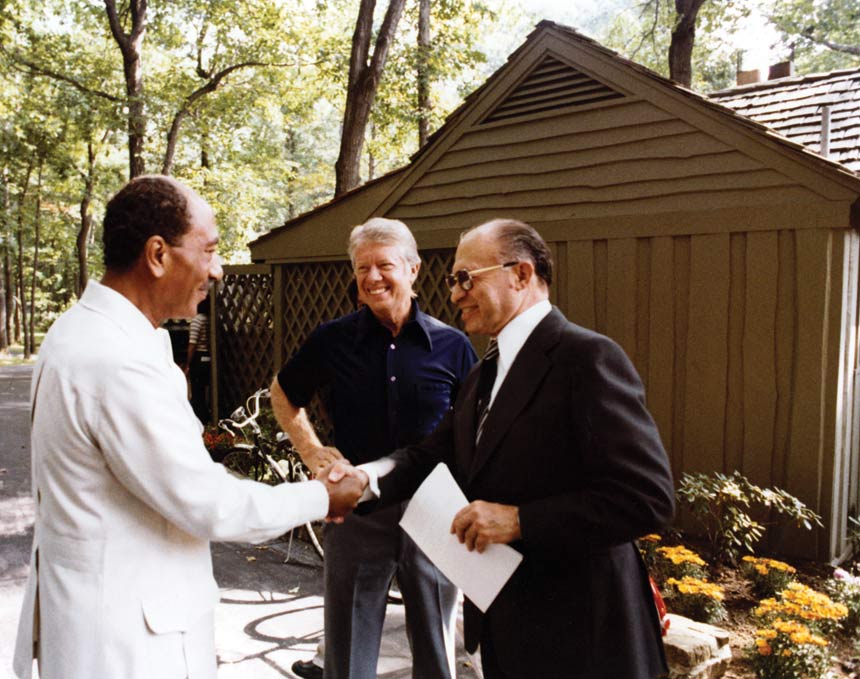

If ever there was an area in which Carter’s strengths as well as his limitations were evident, it was the Middle East. He increased arms sales to solidify our alliances with moderate Arab states against the Soviet Union, despite angry objections from Israel and vehement opposition by the American Jewish leadership. At the same time, he was a Middle East peacemaker par excellence, building on Egyptian president Anwar el-Sadat’s historic trip to Jerusalem. Carter stepped in to break the impasse in negotiations between Israel and Egypt by summoning both sides to his retreat at Camp David in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains, near Washington.

This was a courageous, almost reckless gamble of his presidential influence, against the virtually unanimous opposition of his own advisors. But the accord negotiated over 13 cliff-hanging days in 1978 represented one of the greatest feats of personal presidential diplomacy in American history. He then took the risky step of going to the region in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the peace effort and convert the Camp David Accords into a binding treaty that removed Israel’s strongest Arab neighbor from the battlefield after five wars and that has remained the foundation of American foreign policy in the Middle East for almost 40 years.

Carter’s accomplishments in domestic policy have also stood the test of time, despite his distant attitude toward Congress. The measures most directly affecting ordinary Americans brought lower air fares and cheaper goods to homes and businesses by deregulating the airline, trucking, and railroad industries, and beginning the restructuring of the communications and banking industries. Carter revolutionized America’s energy future before other political leaders saw the dangers of America’s growing dependence on Middle East oil. He persuaded Congress to pass three major energy bills in four years, which set the United States on a new, revolutionary course of conservation, alternative energy sources, and greater production of traditional American fossil fuel resources. The ending of federal price controls, together with the creation of a Department of Energy, soon allowed the United States to reclaim its position as one of the world’s leading producers of natural gas and crude oil.

As Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve for three presidents, says: “Carter anticipated many of the programs that his successor Ronald Reagan embraced. He fostered major deregulation of transportation, communication, and banking.”

Carter was also the greatest environmental president since Teddy Roosevelt, and none since have come close to his accomplishments. He set more land aside for national parks than had all his predecessors combined, overriding persistent demands by the Republicans and oil companies to open huge swaths of Alaskan land to oil drilling. Over the strenuous objections of the automobile industry, he issued far-reaching fuel efficiency standards, forcing America’s automakers to produce cars that could compete with Japan’s.

Carter was the first “New Democrat” — more conservative on spending than the traditional base, a social and civil rights progressive, and an engaged liberal internationalist seeking diplomatic rather than purely military solutions. In the end, he was too conservative for the liberals and too liberal for the conservatives. He departed from Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal without abandoning it, and supported Johnson’s Great Society without expanding it, thus creating a new framework for the Democratic Party. This was a difficult political balancing act he could not always master in the White House, although he campaigned brilliantly as a Southerner reaching out to the Northern white working class. Carter constantly had to tack between the domestic spending demands of his party’s congressional leadership and its liberal wing and his own and his Southern supporters’ inherent fiscal conservatism — a reflection of their historic rejection of federal power.

As an Annapolis-trained submarine officer, Carter was no pacifist but was nevertheless very cautious about deploying American military power.

It would be left to Bill Clinton, another Southerner and a natural politician with an extraordinary grasp of policy, to deploy his rhetorical mastery in articulating and holding a centrist path for the party better than the man who had begun to map the way under the worst possible economic circumstances — Jimmy Carter the engineer, businessman, and stern moralist.

Like his idol, Harry Truman, whose favorite slogan, “The Buck Stops Here,” he kept on his Oval Office desk, Carter left the White House a widely unpopular president. But Truman now is recognized more for his achievements than his faults, and I hope there will be a similar reassessment of Jimmy Carter’s term in the White House. His administration was consequential, and America became a better and more secure country because of it.

Stuart E. Eizenstat has served as U.S. Ambassador to the European Union and Deputy Secretary of the Treasury. An international lawyer in Washington, D.C., he is also the author of Imperfect Justice.

This article is featured in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Ford, Nixon, and the Controversies behind Presidential Pardons

On September 8, 1974, in one of the most controversial shows of presidential clemency, Gerald Ford pardoned “all offenses against the United States” that Richard Nixon may have committed between January 20, 1969 and August 9, 1974.

According to Alexander Hamilton, the Constitution gives the president the power to pardon criminals in order “to restore tranquility to the commonwealth” in politically divisive cases. But sometimes, instead of tranquility, pardons further divided the country and even destroyed presidents’ careers. Although few pardons are without controversy, some have created more waves than others.

Here’s a look at some of the more memorable pardons by our nation’s presidents.

George Washington and the Whiskey Rebellion

George Washington granted the first presidential pardon when he spared the lives of two men who’d been sentenced to hang for their part in Pennsylvania’s Whiskey Rebellion. Washington had sensed the rebellion was dying away and didn’t want to revive the cause by hanging men for treason. Hamilton didn’t approve; he wanted to make an example to other tax resisters. But pardoning the men shifted the country’s attentions away from the fading rebellion and helped defuse lingering anti-government feelings.

Andrew Johnson and the Confederacy

Andrew Johnson had the same idea in 1865, but not the same results. After the Civil War ended, he sought to reunite the country by pardoning thousands of former office-holders of the Confederacy. He believed he was carrying out the lenient attitude that President Lincoln would have wanted. Within a year of the war’s end, Johnson had granted pardons to more than 6,000 former officials of the Confederacy.

Members of the Republican Party were furious with Johnson. They believed he was giving power back to the rebels and traitors who’d started the war. Some senators thought Johnson was guilty of treason for aiding the Union’s former enemies. The Republicans split between the pro- and anti-Johnson factions. In 1868, Johnson’s opponents began impeachment hearings against him. Johnson escaped impeachment by one vote, but the Republicans, and the nation, remained divided between pro- and anti-leniency factions for years.

Harry Truman and the Conscientious Objectors

During World War II, over 15,000 Americans objected to participating in the war and refused to serve in the military. When the war ended, President Truman asked a board to review these cases to see who truly qualified for conscientious-objector status. The board found 1,500 objectors who had legitimate religious convictions barring them from service. Truman pardoned these men on December 23, 1947.

Amnesty activists pleaded with Truman to pardon the others, but he refused. Believing he’d released all honest draft resisters, he regarded the remaining conscientious objectors as “just plain cowards or shirkers.”

Jimmy Carter and the Draft Dodgers

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter was considering the fate of American men who’d refused to serve in the Vietnam War. The war had ended, but thousands who had evaded the draft were still in prison. Carter knew Americans were sharply divided over the war. He thought pardoning the draft dodgers would help resolve the divisions and move the country forward.

On January 21, 1977, he extended amnesty to all men who’d failed to register for the draft or who fled the country to avoid conscription. This included more than 50,000 American men who’d fled to Canada. The amnesty did not extend to over 500,000 men who were imprisoned for going AWOL while in uniform.

The pardon was welcomed by the families of draft dodgers, but veterans who’d served in Vietnam were infuriated. Resentment among Americans who’d supported the war only deepened. The pardon helped erode Carter’s support and probably contributed to his failed re-election bid.

Ford and Nixon

One of the most controversial presidential pardons was Gerald Ford’s pardoning of Richard Nixon. Ford must have known he’d lose some of the general support he’d enjoyed when he took over the White House after Nixon left. But he’d seen the country preoccupied by the Watergate scandal for over a year, and he knew a lengthy, public trial of Nixon, which would consume at least another year, would further divide pro- and anti-Nixon camps and distract the nation from pressing economic and international issues.

Ford was ready to move on, but the country wasn’t. Though praised by legislators in both parties, he was criticized by many Americans who wanted to see justice meted out to Nixon. A Gallup poll that month showed most Americans disapproved of the pardon. Instead of restoring tranquility to the nation, as he’d hoped, Ford had raised the Watergate issue to even greater prominence. The unpopularity of this action probably cost Ford the presidential election in 1978.

Pardons and Politics

Since then, critics have seen political motives in presidential pardons. Some considered President George H.W. Bush’s pardoning of six participants in the Iran-Contra Affair as a convenient way of protecting himself from having to testify on the affair before Congress. Some of President Clinton’s pardons were viewed by critics as efforts to protect major donors or buy votes among minority groups. In 2007, President George W. Bush commuted the prison sentence of vice-presidential advisor Lewis Libby, who’d been convicted for obstruction of justice and perjury. Bush’s action was so widely considered a cover-up for the president’s involvement that the House Judiciary Committee investigated whether pardons were being used for political gain.

It’s impossible for a president not to gain political advantages by extending a pardon. But the chief motive in pardoning should always be what Hamilton described in 1787 — restoring tranquility to the commonwealth — even if some Americans aren’t ready to forgive.

Featured image: Gerald R. Ford (White House Archives, Gerald R. Ford Library)