Although it is conventional wisdom that Jimmy Carter was a weak and hapless president, I believe that the single term served by the 39th president of the United States was one of the most consequential in modern history. Far from a failed presidency, he left behind concrete reforms and long-lasting benefits to the people of the United States as well as the international order.

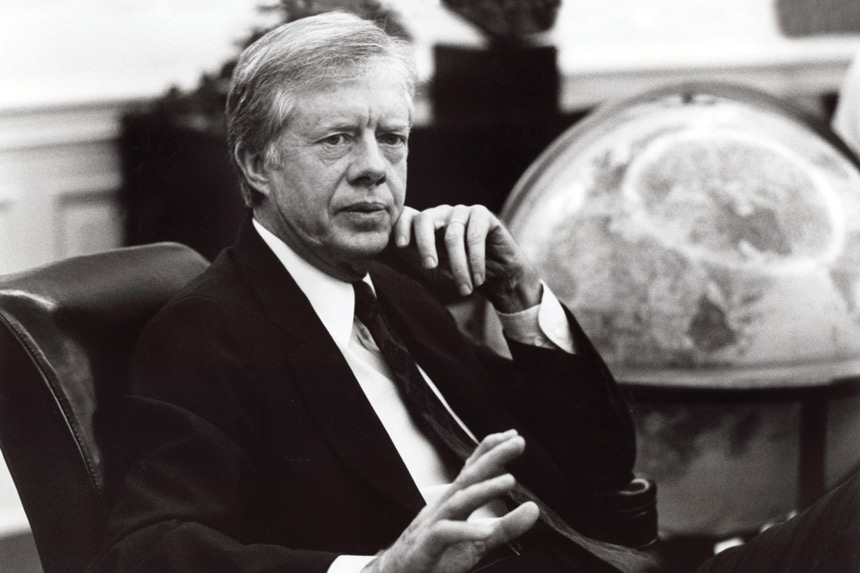

Let me be clear: I am not nominating Jimmy Carter for a place on Mount Rushmore. He was not a great president, but he was a good and productive one. He delivered results, many of which were realized only after he left office. He was a man of almost unyielding principle. Yet his greatest virtue was at once his most serious fault — he took on intractable problems with comprehensive solutions while disregarding the political consequences. He could break before he would bend his principles or abandon his personal loyalties.

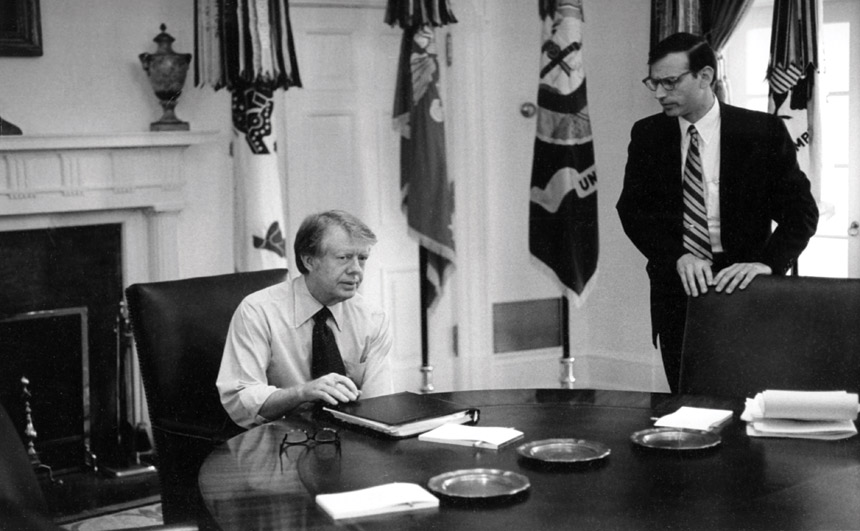

An extraordinarily gifted political campaigner, he nevertheless believed that politics stopped once he entered the Oval Office and that decisions should be made strictly on their merits. But to be truly effective, a president cannot make a sharp break between the politics of his campaign and the politics of governing if he wants to nurture an effective national coalition. This Carter not only failed to achieve — he did not want to. Time and again he would say, “Leave the politics to me,” while in fact he disdained politics.

Possibly as a result, critics disregard the breadth of Carter’s accomplishments and accuse him of being an indecisive president. That is simply not true; if anything, he was too bold and determined in attacking too many challenges that other presidents had side-stepped or ignored, such as energy, the Panama Canal, and the Middle East, while nevertheless achieving lasting results. The art of presidential compromise rests on the ability to obtain at least half of what the administration proposes to Congress and then to claim victory. President Carter was maladroit at this political sleight of hand largely because he was uncomfortable with compromising what seemed to him so obviously the right course.

One reason his substantial victories are discounted is that he sought such broad and sweeping measures that what he gained in return often looked paltry. Winning was often ugly: He dissipated the political capital that presidents must constantly nourish and replenish for the next battle. He was too unbending while simultaneously tackling too many important issues without clear priorities, venturing where other presidents felt blocked because of the very same political considerations that he dismissed as unworthy of any president. As he told me, “Whenever I felt an issue was important to the country and needed to be addressed, my inclination was to go ahead and do it.”

But even with Carter’s limitations, I refuse to let the mistakes overwhelm the achievements. We still benefit from his vision of the challenges faced by our country and the world, from his willingness to confront and deal directly with them regardless of the political cost, and finally from his essential integrity. He gained the presidency in a post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era of cynicism about government with a personal pledge that “I will never lie to you” — a promise that he worked hard to keep, and is now more important than ever in a new era of “fake news” and post-truth political rhetoric.

Public recognition of Carter’s legacy of accomplishments has been obscured by inexperience in the critical early stage of the administration; iconoclastic, idiosyncratic decision-making; double-digit inflation and interest rates; internal Democratic Party strife; and the Iran hostage crisis. But, like the successes of Truman, Clinton, and the senior Bush, Carter’s achievements shine brighter over time, few more than his unique determination to put human rights at the forefront of his foreign policy from the start of his presidency.

He gained the presidency in a post-Vietnam and post-Watergate era of cynicism about government with a personal pledge that “I will never lie to you.”

At the time, this shift from the realpolitik of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger was derided by some as utopian, and indeed some events demanded responses that did take precedence over human rights. But when backed by actions like cutting military aid to Latin American dictatorships such as Chile and Argentina, his human rights policies helped convert most of our Latin American neighbors from authoritarian rule to democracy.

The administration’s public advocacy of human rights also weakened the Soviet empire by attacking its soft underbelly — its domestic repression. No less than Anatoly Dobrynin, the long-time Soviet ambassador to Washington, conceded that Carter’s human rights policies “played a significant role in the … long and difficult process of liberalization inside the Soviet Union and the nations of Eastern Europe. This in turn caused the fundamental changes in all these countries and helped end the Cold War.”

As an Annapolis-trained submarine officer, Carter was no pacifist but was nevertheless very cautious — perhaps excessively so — about deploying American military power until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. No American soldiers were killed in combat on his watch. He signed the second and most ambitious Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) with the Soviet Union, which served as the basis for future arms limitation agreements. At the same time, he did not hesitate to support cutting-edge weapons technology.

Despite allied resistance, Carter persuaded European governments to begin deploying middle-range nuclear weapons in Europe to counter the Soviets’ new mobile missiles. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, later called this allied response a significant factor in convincing him that his predecessors’ policies of military threats to the West should be replaced by disarmament and accommodation.

In another bold step, taken over ferocious and emotional opposition from conservatives, his administration negotiated a treaty with Panama that yielded American sovereignty over the canal, avoiding an almost certain guerrilla war by Panama against this vital sea link, while fully protecting America’s priority use of the vital seaway. It led to a giant step in elevating U.S. relations with Latin America. And while Nixon and Kissinger deserve great credit for their dramatic outreach to the People’s Republic of China, they could go no further because of fierce opposition from the Taiwan lobby, a major force in the Republican Party. It fell to Carter to take the lasting step of normalizing diplomatic relations with the most populous nation in the world as it grew into a power that could not be ignored.

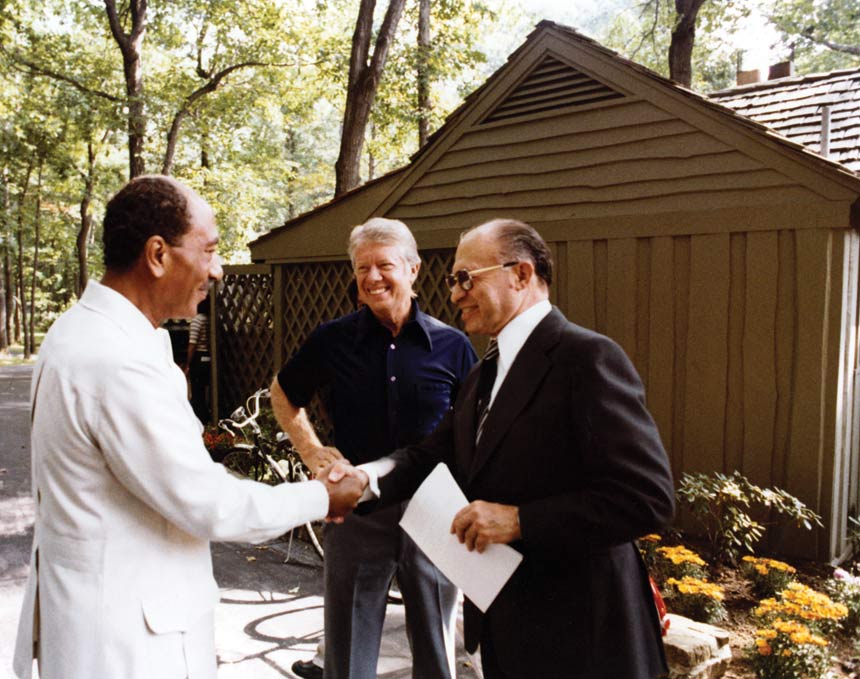

If ever there was an area in which Carter’s strengths as well as his limitations were evident, it was the Middle East. He increased arms sales to solidify our alliances with moderate Arab states against the Soviet Union, despite angry objections from Israel and vehement opposition by the American Jewish leadership. At the same time, he was a Middle East peacemaker par excellence, building on Egyptian president Anwar el-Sadat’s historic trip to Jerusalem. Carter stepped in to break the impasse in negotiations between Israel and Egypt by summoning both sides to his retreat at Camp David in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains, near Washington.

This was a courageous, almost reckless gamble of his presidential influence, against the virtually unanimous opposition of his own advisors. But the accord negotiated over 13 cliff-hanging days in 1978 represented one of the greatest feats of personal presidential diplomacy in American history. He then took the risky step of going to the region in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the peace effort and convert the Camp David Accords into a binding treaty that removed Israel’s strongest Arab neighbor from the battlefield after five wars and that has remained the foundation of American foreign policy in the Middle East for almost 40 years.

Carter’s accomplishments in domestic policy have also stood the test of time, despite his distant attitude toward Congress. The measures most directly affecting ordinary Americans brought lower air fares and cheaper goods to homes and businesses by deregulating the airline, trucking, and railroad industries, and beginning the restructuring of the communications and banking industries. Carter revolutionized America’s energy future before other political leaders saw the dangers of America’s growing dependence on Middle East oil. He persuaded Congress to pass three major energy bills in four years, which set the United States on a new, revolutionary course of conservation, alternative energy sources, and greater production of traditional American fossil fuel resources. The ending of federal price controls, together with the creation of a Department of Energy, soon allowed the United States to reclaim its position as one of the world’s leading producers of natural gas and crude oil.

As Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve for three presidents, says: “Carter anticipated many of the programs that his successor Ronald Reagan embraced. He fostered major deregulation of transportation, communication, and banking.”

Carter was also the greatest environmental president since Teddy Roosevelt, and none since have come close to his accomplishments. He set more land aside for national parks than had all his predecessors combined, overriding persistent demands by the Republicans and oil companies to open huge swaths of Alaskan land to oil drilling. Over the strenuous objections of the automobile industry, he issued far-reaching fuel efficiency standards, forcing America’s automakers to produce cars that could compete with Japan’s.

Carter was the first “New Democrat” — more conservative on spending than the traditional base, a social and civil rights progressive, and an engaged liberal internationalist seeking diplomatic rather than purely military solutions. In the end, he was too conservative for the liberals and too liberal for the conservatives. He departed from Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal without abandoning it, and supported Johnson’s Great Society without expanding it, thus creating a new framework for the Democratic Party. This was a difficult political balancing act he could not always master in the White House, although he campaigned brilliantly as a Southerner reaching out to the Northern white working class. Carter constantly had to tack between the domestic spending demands of his party’s congressional leadership and its liberal wing and his own and his Southern supporters’ inherent fiscal conservatism — a reflection of their historic rejection of federal power.

As an Annapolis-trained submarine officer, Carter was no pacifist but was nevertheless very cautious about deploying American military power.

It would be left to Bill Clinton, another Southerner and a natural politician with an extraordinary grasp of policy, to deploy his rhetorical mastery in articulating and holding a centrist path for the party better than the man who had begun to map the way under the worst possible economic circumstances — Jimmy Carter the engineer, businessman, and stern moralist.

Like his idol, Harry Truman, whose favorite slogan, “The Buck Stops Here,” he kept on his Oval Office desk, Carter left the White House a widely unpopular president. But Truman now is recognized more for his achievements than his faults, and I hope there will be a similar reassessment of Jimmy Carter’s term in the White House. His administration was consequential, and America became a better and more secure country because of it.

Stuart E. Eizenstat has served as U.S. Ambassador to the European Union and Deputy Secretary of the Treasury. An international lawyer in Washington, D.C., he is also the author of Imperfect Justice.

This article is featured in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I have just completed the Time magazine article of you and Rosalyn working on a Habitat project in Indiana. Congratulation on your 35th year as a “project worker” working on such worthy causes, such as a home for a fellow human being. Thank God, she and her children will have an affordable home because of caring persons.

You are my “hero”! Both you and Rosalyn are a model that many, including myself, should emulate. I, like you are, am a Democrat. I voted for you in both elections, with a strong hope for your re-election. I am a supporter of your outreach programs, contributing when possible.

I ascribe to your basic philosophy of lifestyle, trusting God for all things in life. I am an 82-year-old male, working until I was 74 years of age. God has been so good to me, supplying all my needs, both physical and spiritual. It is such inspiration to read an article where you can feel the passion, relate to the simple lifestyle that you follow, your humility toward mankind, and your stated faith in God. The both of you are to be commended for your magnanimity and rectitude of giving, loving, and supporting so many of those folks who have difficulty supplying their needs, that many of us take for granted.

Your outlook for our nation is one of optimism and hope. I, like you do not ascribe to the philosophy, life style, or the “fake” grandiosity that our current President displays. I, too pray for Mr. Trump, but the sooner he leaves his position, the better our country would probably be. This is an opinion of a voter who has voted in every election beginning with President Kennedy to the present.

I would like to thank you for all your dedicated service to our country. My desire would be that more people like you could be elected to higher offices, who have a desire to do more for their country than for themselves. As a teacher of God’s Word in a small local Baptist church, adjuring my class to study God’s Word, pray for others as you do for yourself, and to put forth an action that matches our words. I can feel within, from reading this article, some of your books, and the lifestyle you project, that the world would be a much better place, if more people would illustrate what you demonstrate.

Mistakes are made by all people, but your contributions to America and society have far outweighed any negatives while serving as President. It wold be a blessing to have people like Jimmy Carter serving in the White House today. His candor, lifestyle, and Christian attitude far outweigh those who have served as president after he left office.

May God bless you and Rosalyn with good health for promoting, Jesus Christ, human rights, peace, and love for one another.

Stuart Eizenstat’s feature sheds new light and perspective on a President whose overlooked accomplishments laid the groundwork for future Presidents to complete what he himself could not in four years. Carter was the bridge between the complicated era of his immediate predecessors, and a largely successful successor.

Carter had a lot crashing down on him in 1979 and ’80 no President had had before or since, and did the best he could at the time. Today we need to look at the complete picture of that time long past, the failures yes; but also his successes as well. Mr. Eizenstat does both in a fair, balanced manner.

Mr. Carter has continued to do great work for America as a former President he continues to this day. This also includes the dignified way a President (former or not) should conduct himself. Ideally this would return with future Presidents, but with everything sooo out of control in this country, everyday, 24/7, it seems unlikely. The die seems permanently cast. Less than 20 years in, the 21st century has proven to be drastically different from the 20th, with any kind of dignity or class being one of the biggest casualties never to return.

Jimmy Carter was brought up in the south, and while perhaps not anti-semitic, he certainly was no friends to Jews,

As president, he put these feelings aside, much to his credit, and truly considerd America first during his administration.

But once he became a normal citizen again, his feelings for Jews resurfaces resulting in his caling Israel an Apaetide state.