Did the Post See World War I Coming?

In the months following the start of World War I, government leaders on both sides expressed surprise and dismay to find themselves at war. Nobody, they said, had expected it, and certainly nobody wanted it. A Serbian terrorist had simply shot the heir to the Austrian empire. The next they knew, Austria had declared war on Serbia, which prompted Russia to mobilize its army. This caused Austria’s ally, Germany, to declare war on Russia. France then declared war on Germany, and soon Great Britain joined in, followed the next year by Italy.

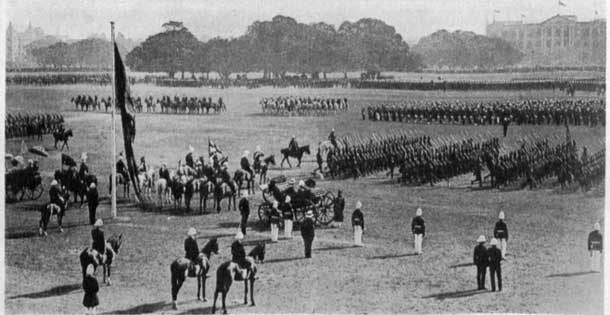

June 20, 1914 © SEPS

Surely someone must have seen “The Great War” approaching. How could something big enough to cause four years of fighting, 10 million deaths, and the end of three monarchies simply show up without any warning?

Americans were baffled. They had been paying little attention to Europe since the U.S. had forced an ailing Spanish empire to relinquish its Cuban and Philippine colonies. Generally, Americans were happy to ignore Europe’s problems and focus on their own prosperity.

The U.S. in 1914 was still a principally rural country, which had changed little since the 19th Century. The average American lived a horse-powered life on a farm or in a small town, and what he knew of the world came from a local newspaper or from magazines arriving by mail. If he was among the two million subscribers to the Post, however, he might not have been as surprised by the outbreak of war as were the crowned heads of Europe.

Just one month prior to the start of the war, Post journalist Will Payne reported from Europe, where he had been researching finances on the Continent. He learned that Italians paid more taxes than any other nation in Europe—and were glad to do it. Taxes were essential to maintaining their army, Italians told him, and preventing France and Austria from returning to rule them. In “Barracks and Beggars,” Payne reported that the people of Italy would pay their last cent and put every one of their men in uniform before submitting again to foreign domination.

When Payne crossed the border into France, he found the same militaristic attitude, but in this case the cause for concern was Germany. The French overwhelmingly supported the stiff taxes that were building up their army, though it consumed nearly half the national budget. Nor did the French object when the government extended the length of mandatory national service from two to three years. A banker told Payne, “I was in favor of that, and so, you will find, were a majority of Frenchmen. Look at what they are doing in Germany, with their new regiments and extraordinary war tax. If they arm, we must arm. It is the price of our life. Germany hates us as much as ever. To disarm would be to commit suicide.” Payne added, “nearly all Frenchmen talk the same way.”

June 20, 1914 © SEPS

The French believed that military training not only kept the country strong but gave pride to its young men, as well as an appreciation of order and hierarchy. “At least a dozen men, first and last, emphasized the point that it taught obedience to authority; or, as one of them more accurately put it, ‘It teaches people that some must command and some must obey.’”

It was a similar story in Berlin, where Payne found “the German businessman speaks of his war taxes as insurance—that is, he regards the tax receipt as a policy of insurance that for another twelve months no British cruiser will shoot the roof off his warehouse.”

The militant spirit had infected Great Britain as well. The British feared losing the global dominance of its navy, particularly since Germany had begun expanding the number of warships. And so Parliament was continually increasing the budget to expand the Royal Navy. But a naval victory over Germany would be useless, the ministers argued, unless a strong, well-drilled British army could secure victory on land as well. So the army’s budget had to be increased as well. Meanwhile, “elderly gentlemen in possession of pleasant jobs and comfortable incomes” insisted that the young men of England required military drill and discipline to guard their character and protect them from dangerous social ideas.

June 20, 1914 © SEPS

All the nations of Europe, Payne found, were locked in an ever-escalating spiral of military preparation. Every country feared the imminent domination by another.

So, for example, the German Kaiser would call on his nation to ensure its security with more men for its army and more millions for weapons. Russia and France would then call up more men for service and hike their taxes to regain the balance of power. And so Germany would launch yet another campaign to gain a strategic edge.

“Militarism is costing Europe about two and a half billion dollars a year to support in idleness some five million able-bodied men who might be productively employed,” Payne wrote, “and its path still pursues an upward spiral.”

He recognized the militant attitude would seem strange to readers of the Post. “Americans think of war about twice in a decade, and then with no very keen interest,” he wrote. “In Europe they think of it all the time.”

It wouldn’t have surprised him that, when the governments of Europe declared war, the news was welcomed by delirious crowds, who jubilantly marched up and down the streets of Berlin, Paris, St. Petersburg, and London. Men not already in uniform rushed to join the great cause, which would liberate their country, at last, from the perennial threat of some neighboring country.

The leaders of Europe’s government might have been surprised that the war came as it did, when it did, but they shouldn’t have been shocked by the war itself. As the Post had been reporting, they had been stoking the enthusiasm for it for years.