Rockwell in the 1960s – Part II

The man with his pipe makes a cameo appearance.

We’re continuing our tour of Rockwell by decades with Part Two of his 1960s illustrations, featuring covers that don’t exactly look like “Rockwells.”

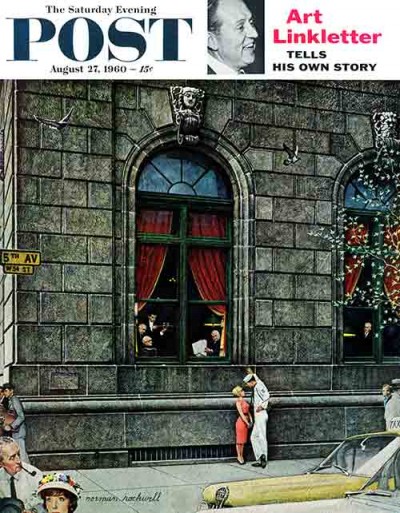

“In Fellowship Lies Friendship”– August 27, 1960

“In Fellowship Lies Friendship”

from August 27, 1960

This rather daunting edifice is the University Club of New York. The club’s motto was “In Fellowship Lies Friendship,” and the fellows inside seem to be interested in the “friendship” developing outside.

Also interested in the tall sailor chatting up the shapely blonde are a few bystanders. Two of those rather non-pedestrian pedestrians are in the lower left corner—Mr. Rockwell, we presume, walking alongside his daughter-in-law, Gail.

What appears to be a simple scene is actually quite detailed. I for one am amazed at the “texture” in the stone. The birds flying by are easy to miss, and leave it to Rockwell to be faithful to the Italian Renaissance details, including the unusual keystones above the windows. The building is still an architectural landmark today.

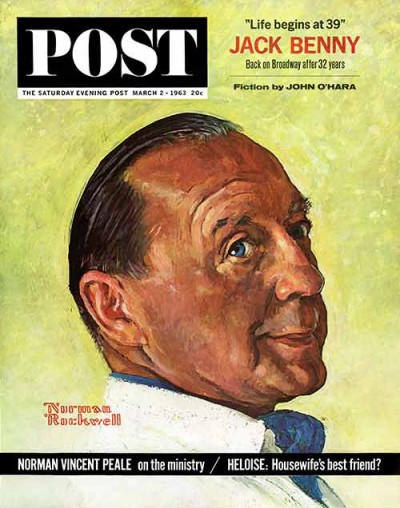

“Well!” (Jack Benny) –March 2, 1963

“Well!”

(Jack Benny)

from March 2, 1963

Well! What else can one say about Jack Benny? Okay, for you younger readers, the delightful Jack Benny had a way of saying, “Well!” that…well, you just had to be there. This painting could also be called, “I’m thinking, I’m thinking!” as in his standard response to the line “Your money or your life!” Really, this stuff wasn’t that corny at the time…

As we saw in the previous feature, Rockwell painted world figures in far-flung places, but, interestingly, he was nervous about meeting the beloved comedian. He called Bill Davidson of the Post and told him, “I’m really nervous about meeting this Benny fellow. Would you be good enough to help me over the hurdle?” Ironically, about a half an hour earlier, Benny, who was beloved by millions and the friend of presidents and kings, called Davidson with the same request. He was nervous about meeting the great Norman Rockwell. So Davidson was there for the meeting. Hey, world leaders come and go. Benny and Rockwell were classics!

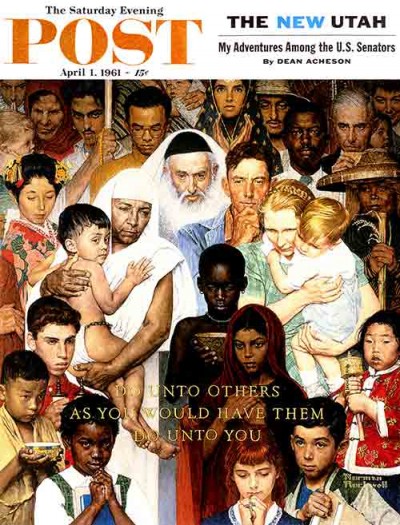

“The Golden Rule”– April 1, 1961

“The Golden Rule”

from April 1, 1961

Norman Rockwell, whose first Saturday Evening Post cover appeared in 1916, was still painting classics 45 years later in 1961. Taking a serious turn, he created “The Golden Rule,” which is, of course, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Oddly enough, the models who depicted the humanity of many nations, all came from the general area of Rockwell’s studio. Rockwell had a passion for costumes and had collected many from his travels abroad. Of the rabbi, the artist chuckled, “he’s Mr. Lawless, our retired postmaster. I put whiskers on him, and I think he fits the part quite well, even if he is a Catholic.” Barely visible in the upper right corner is a face painted by memory: Rockwell’s late wife, holding their first grandson, a child she hadn’t lived to know.

Rockwell received the Interfaith Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews for this cover.

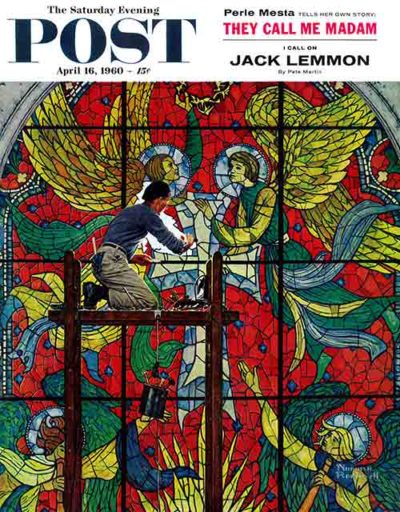

“Stained Glass Artistry”– April 16, 1960

“Stained Glass Artistry”

from April 16, 1960

Among our Rockwells that don’t look like Rockwells, we have this Easter 1960 cover. The idea came from a trip Norman took to Westminster Abbey in London, where a craftsman was high on a scaffold repairing a stained glass window.

Oh how the artist toiled to capture that luminosity of the backlit stained glass. He just couldn’t do it. Finally, he found stained glass designers Rowan and Irene LeCompet of New York and they traveled to Rockwell’s studio bearing detailed plans of a window they had designed for a Washington church. That’s Rowan LeCompet up on the scaffold repairing a break. Rockwell studied church window after church window, inside and out, before he finally captured that radiant quality.

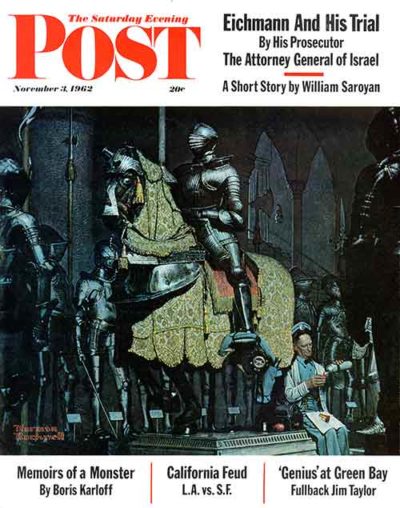

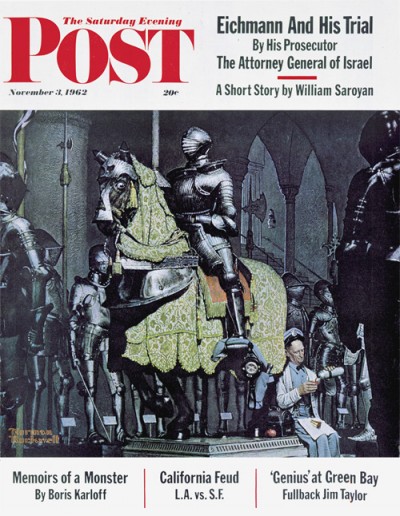

“Midnight Snack”– November 3, 1962

“Midnight Snack”

from November 3, 1962

This cover is another example of Rockwell’s attention to minute detail, and an example of his wild sense of humor. The scene takes place at the Higgins Armory Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts, which must be a fascinating place to visit. The knight in shining armor atop the horse was a display that caught Rockwell’s fancy. The detail in the tapestry is wonderful. Not part of the collection, but a figment of Norman’s imagination, is the guard having a midnight snack. And we really, really hope the disapproving glare of the horse was part of Norman’s fancy, too!

Previous: 46483 Rockwell Rockwell in the 1960s – Part I

Rockwell in the 1960s – Part I of II

We’re beginning a tour of Rockwell by decades, beginning with the 1960s and traveling back to the 19-teens. We hope you’ll join us for the whole fascinating journey!

“Rockwell Paints Nehru”– Feb 13, 1960

“Rockwell Paints Nehru”

from January 19, 1963

Forget freckle-faced boys, scruffy dogs and swimming holes. Rockwell was a seasoned traveler in the 1960s, often painting world leaders along the way.

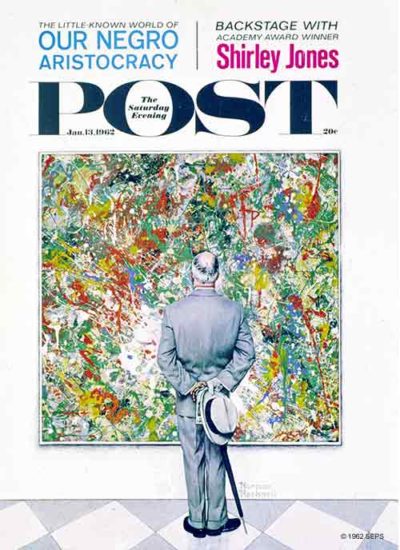

“The Connoisseur”– January 13, 1962

“The Connoisseur”

from January 13, 1962

You can stare at the man staring at the Jackson Pollock-like picture all day and still not decide if he is thinking of whipping out his checkbook to buy it, or wondering, “What in blue blazes is going on here?”

Rockwell himself attended some classes “in modern art techniques. I learned a lot and loved it.” He had fun with this one. He put the canvas on the floor, dipping into paints and splashing them far and wide. It happened that a worker was washing the windows of his studio, so the artist invited him to help. The man climbed to the top of a ladder and obligingly dumped a can of white paint on the canvas below. One can’t help but wonder whatever happened to the laborer who actually helped Norman Rockwell paint a Post cover!

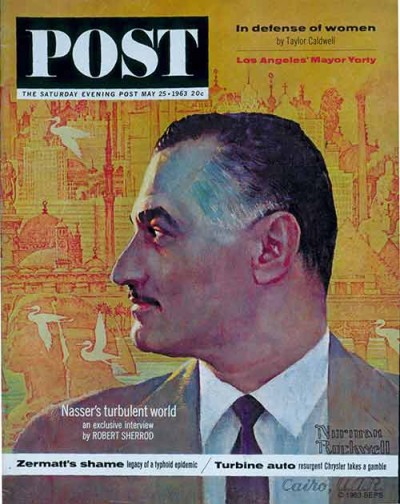

“Gamal Abdel Nasser”– May 15, 1963

“Gamal Abdel Nasser”

from May 15, 1963

Not what you think of as a “Rockwell,” is it? But Norman Rockwell was a great portrait painter (see the paintings he did of candidates Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy in “Presidential Post Covers” from February 19, 2011). Nasser of Egypt was a pivotal figure in world politics since becoming president in 1954.

Nasser knew he was a handsome man and insisted on a frontal view with a toothpaste smile. Rockwell was just as insistent on a profile portrait. The artist would pose him the way he wished and begin sketching and Nasser would turn around and flash that big smile again. Now, clearly Norman was dealing with a powerful world figure, and not one to trifle with. This was a man who had helped organize the overthrow of the Egyptian royal family—a man with many guards around. Big guards. But Rockwell persisted in posing the President as he wanted, and, uncharacteristically, Nasser finally gave in.

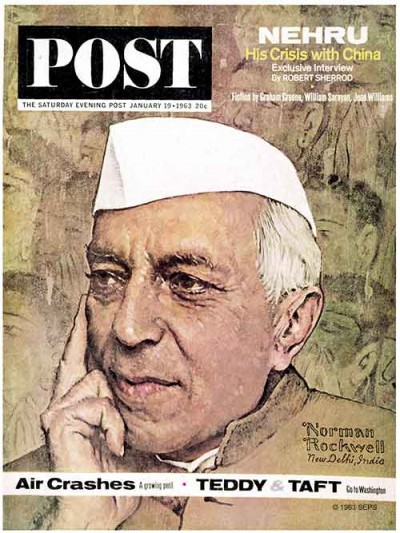

“Nehru”– January 19, 1963

“Nehru”

from January 19 1960

Another day, another hot spot in the world. Rockwell accompanied Post Editor Robert Sherrod to India to report on “the epical struggle between China and India, which engages a third of mankind.” The article included photos of India of the early sixties, including one of college girls getting “emergency rifle training” from an army instructor.

Rockwell and his wife Molly enjoyed India and were invited to Nehru’s home. There they met Nehru’s daughter, Indira Ghandi, a future Prime Minister. The Rockwells were flattered and more than a little startled to find that Madame Gandhi had a room lined with Rockwell prints for her children.

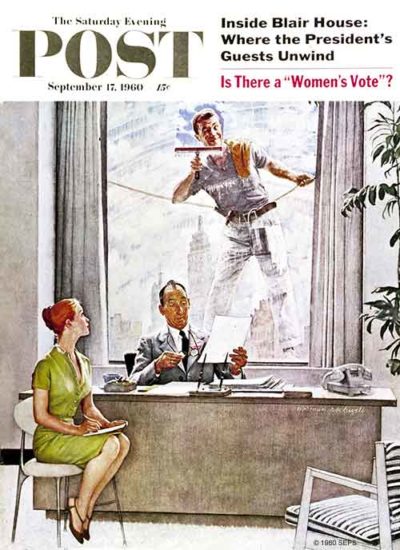

“The Window Washer”– September 17, 1960

“The Window Washer”

from September 17, 1960

“Sakes alive! What ever has come over Norman Rockwell?” mused Post editors. “Does he hold with this sort of behavior?” Actually, Rockwell initially envisioned a different type of woman. He had in mind “a very prim girl, looking shocked,” he told us. “But the idea of youth calling to youth worked out more effectively. The girl isn’t going to date the fellow, however. You may assure the public of that.” Aw, Norman, that would have made a nice ending!

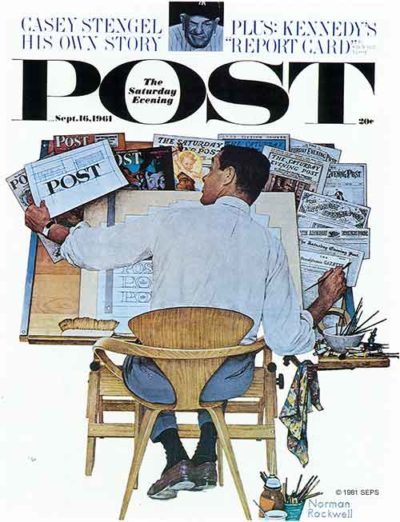

“Modernizing the Post”– September 16, 1961

“Modernizing the Post”

from September 16, 1961

The Pennsylvania Gazette was started in 1729 by an innovative young man named Benjamin Franklin. The Gazette is one of the many mastheads on display on the easel. Although it was the most successful newspaper in the colonies in 1815, long after Franklin’s death, it ceased publication and reportedly became a paper called The Saturday Evening Post. The connection is nebulous, but we remain determined to say we were started by Ben Franklin, so work with us here. Said paper was in dire financial straits by the 1890s and was purchased for $1,000 in 1897 by Cyrus Curtis, publisher of The Ladies’ Home Journal. From time to time, the Post changed its appearance; hence, the varied mastheads you see here.

Norman Rockwell, himself a rather important piece of Post history, depicts art designer Herbert Lubalin deciding on a clean, streamlined “POST.”

Next: Rockwell in the 1960s — Part II

Rockwell Paints Rockwell

We showed you how Rockwell painted himself into his famous cover, “The Gossips” (see Rockwell: Behind the Canvas). Where else has our favorite artist popped up?

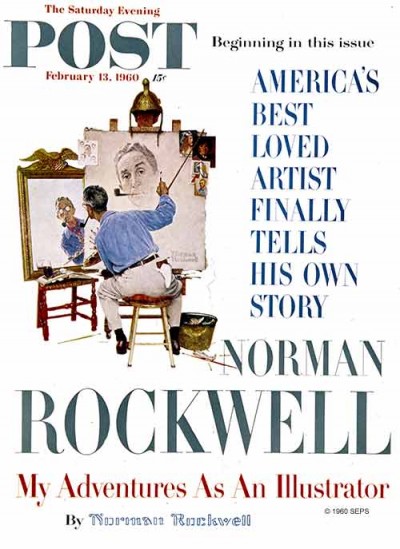

“Triple Self Portrait”– Feb 13, 1960

“Triple Self Portrait”

From Feb 13, 1960

Rockwell pokes fun at himself in 1960’s “Triple Self-Portrait.” The Rockwell in the mirror has foggy glasses. Rockwell’s reasoning for that was so “I couldn’t actually see what I looked like—a homely, lanky fellow—and therefore, I could stretch the truth just a bit and paint myself looking more suave and debonair than I actually am.”

There are a lot of interesting details other than the debonair gent at the easel. A student of great artists, Rockwell had self-portraits of masters pinned to the upper right of his work. We see Durer, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and a funky post-cubist Picasso, all of which Rockwell himself painted.

Rockwell was thrilled when, on a trip to Paris, he saw the helmet that sits atop his easel in an antique shop. He was sure it was centuries old, of Greek origin…or perhaps Roman. After purchasing it, he stopped to observe a fire. He realized the same helmet he was sure was a precious antique was typical Parisian fireman’s gear.

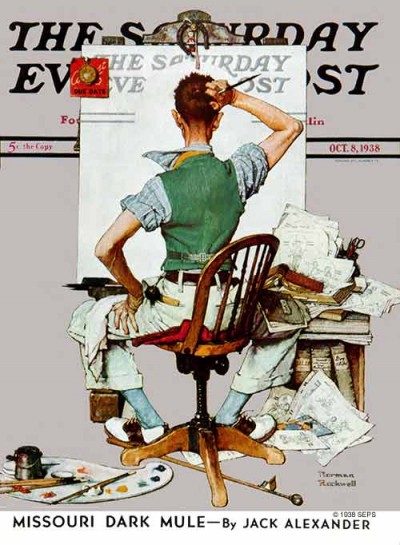

“Blank Canvas” – Oct 8, 1938

“Blank Canvas”

From Oct 8, 1938

Rockwell had done approximately one hundred and forty covers by the time of this whimsical 1938 painting. The Post wasn’t the same without renowned editor George Horace Lorimer (who passed away the previous year) and the great artist was restless. So he did a cover about running dry of ideas because…well, he was. The young artist is a parody of himself: tall, lanky and with the ever-present pipe tucked into a back pocket. There sits that danged blank canvas atop of which rests a pocket watch and lurking deadline. Even the horseshoe isn’t bringing any help…perhaps because it’s upside down.

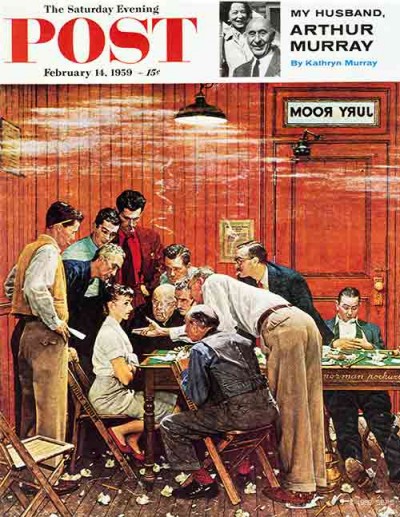

“The Holdout” – Feb 14, 1959

“The Holdout”

From Feb 14, 1959

There is a holdout in this tense jury scene. It has been a long hard deliberation if we read the table detritus and debris on the floor. A lone but determined female is wreaking havoc in the man’s world of 1959.

Most of the models are Rockwell’s friends and neighbors. The artist enjoyed small-town life as he knew many of the faces and could often find just the right one for a particular scene right at home. The gentleman leaning down behind the woman and attempting to be persuasive is our beloved artist and model himself. Rockwell made a sort of Jack Benny joke about it—he appeared in the painting because he wouldn’t have to pay himself a model’s fee. But, we’re sorry, Norman; it appears the lady is immovable.

“A Family Tree” -October 24, 1959

“A Family Tree”

From October 24, 1959

This family tree is a regular “Where’s Waldo?” Okay, “Where’s Norman?” Who is in your family tree? A saloon gal? An aristocrat? A pirate? The possibilities intrigued Rockwell. Before reading on, click on the cover for a close look and see if you can pick out Rockwell. Hint: It’s hard!

Here’s another hint: Most of the men: the gentleman in the cowboy hat, the prospector with the full beard, the Confederate and Yankee soldiers, the pirate, etc., are the same man, and that model was not the artist. How the artist could do so much with one face defies belief. The dour woman with the cameo at her neck (middle right) is…are you ready…the same man! The rather sour, straight-laced minister next to her is Mr. Rockwell himself.

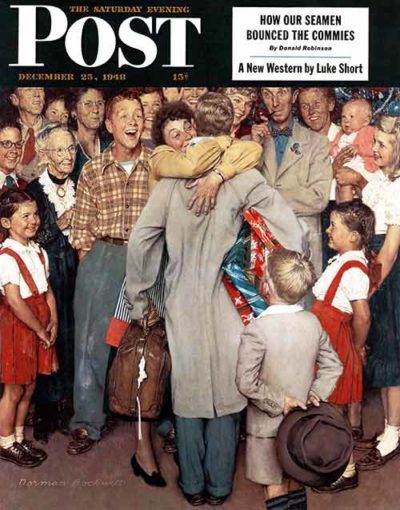

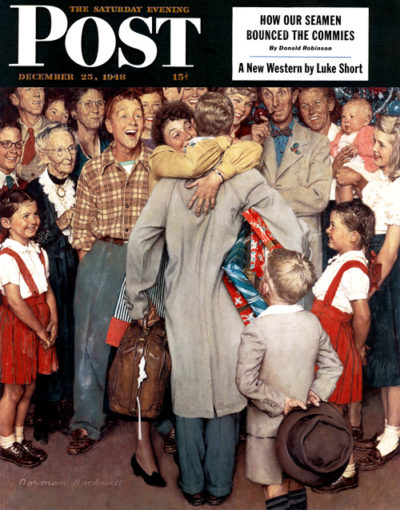

“The Homecoming” -December 25, 1948

“The Homecoming”

From December 25, 1948

How I love this cover! Not only do we see Norman (upper right with his pipe), but the whole family! Hugging the blond young man is Rockwell’s wife, Mary, and yes, although we only see his back, that is eldest son, Jerry, on the receiving end of the embrace. The happy young man in the plaid shirt is middle son, Tommy, and the youngest boy, Peter can be seen with glasses at the far left.

Besides the Rockwell clan, there are various friends and neighbors. One of these was little Sharon O’Neill in the red skirt. Rockwell thought she was so darn cute he painted her twice – as twins! And next to Tommy Plaidshirt is another delightful artist playing the role of Grandma in this happy scene—Rockwell’s friend, Grandma Moses.

Rockwell’s Silly Side

What happens when a fireman (even in a painting) smells smoke or plumbers are turned loose in a fancy boudoir? Our favorite artist has the answers.

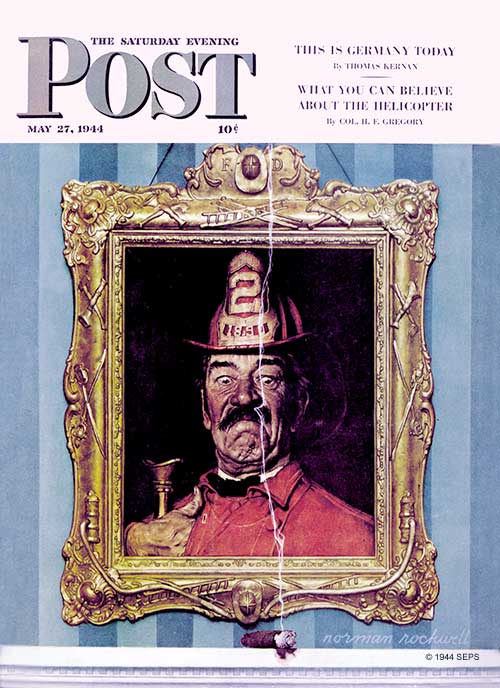

“The Fireman”

This may be the only known time when a picture frame inspired the painting that went into it. Rockwell found this unique frame while browsing through a junk store. Well, if you have an empty frame, you have to fill it, right? Carved into the old find were some artifacts of the fire-fighting profession: axes, ladders, and so on. It practically begged for an old-fashioned fireman to occupy it. So the artist conjured up this gent in the turn-of-the-century uniform, complete with a big, bushy mustache. In a fit of pure goofiness, he added a stiffly disapproving glare and displayed a lit cigar beneath the painting for picture-within-picture fun.

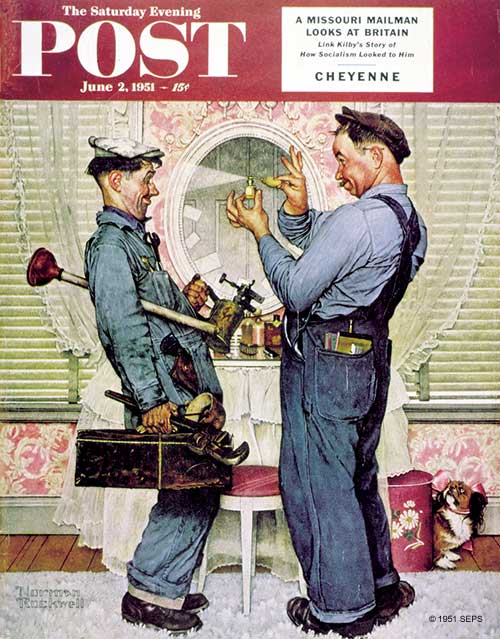

“The Plumbers”

For pure silliness, you can’t beat “The Plumbers” from 1951. Who but Rockwell would come up with a couple of working stiffs in a fancy boudoir? The homeowner is out for the day, but not the indignant, pink-bowed Pekingese. While crawling under dank sinks and unclogging who-knows-what is all well and good, why not have a little fun? “Here, Clyde, let me make you smell pretty!”

As usual, the details are terrific: look at that wallpaper, the grubby coveralls, and the plumbers’ tools (you can click on the cover for a closer view). These guys were actual plumber acquaintances of the artist, and they were asked to bring along their gear. Who else would have friends who looked like Laurel and Hardy?

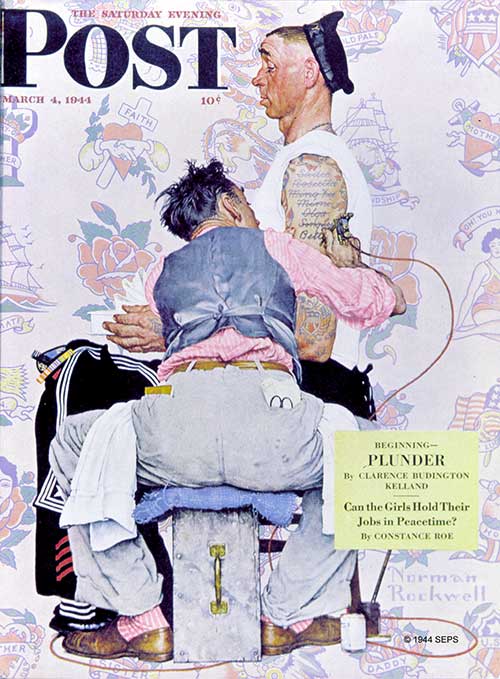

“Tattoo Artist”

During the WWII years, there were many, many serious Post covers with soldiers. If you look up artist Mead Schaeffer at Curtis Publishing, you’ll see armed paratroopers, jungle commandos, and military personnel in a myriad of war activities. Oh, speaking of Mead Schaeffer, he was a buddy of Rockwell’s and posed for this painting as the tattoo artist. He staunchly maintained that Rockwell made his posterior larger than in real life, which Rockwell denied. By the way, Mr. Schaeffer, I dig those socks. Apparently, the issue remains unresolved to this day. The sailor in the painting had apparently been in many ports, but Rosietta, Olga, and the rest are ancient history. This is a new port, and there is a new love-of-his-life. Rockwell even used a sheet of available tattoos as the background.

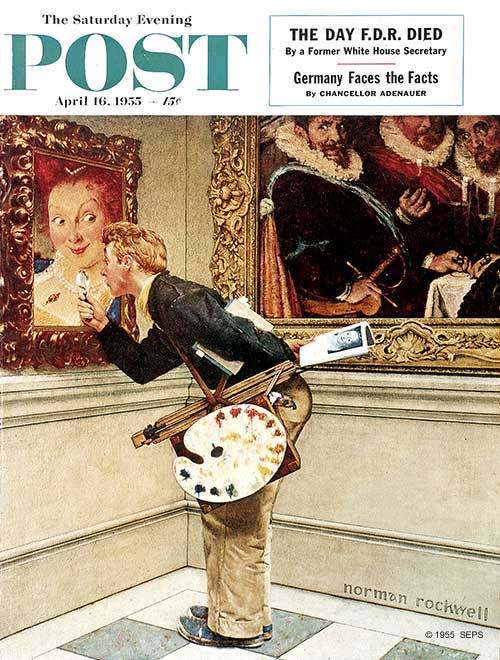

“The Critic”

The young art student is studying a painting that is studying him—an “unstill life,” if you will. Except for the frowning Dutch masters in the other painting, it is all in the family. The art critic studying a locket in the painting is Jerry Rockwell, the oldest son of the artist. The whimsical lady in the painting is his mother, Mary (Rockwell added flaming red hair for fun). Should the student notice the painting looking back at him or look over his shoulder to see the Dutch gents glaring at him, I suspect he would run screaming from the museum and take up another subject to study.

Starting Over

James Kellogg Van Brunt, the pensive musician posing for the November 2, 1929, cover of the Post, was a gentleman about town and a good friend of Norman Rockwell’s. Van Brunt was more than just a model, though; he played a significant role in the creation of this painting, which traces its origin to an ocean voyage four months earlier.

After vacationing in Europe, Rockwell and his wife, Irene, were sailing home to New York along with their close friends, Fred and Edna Peck. While on board, Fred revealed some shocking news to Rockwell: He informed him that Irene wanted a new life with someone else—Fred’s own brother-in-law. Awkward!

A few days after arriving home, Rockwell retreated to the sanctuary of his studio and his work. However, once inside, he found it difficult to do anything but stand and stare, let alone be creative. After a week of producing very little, he sought counsel from his old friend Van Brunt. A veteran of two wars and 45 years Rockwell’s senior, Van Brunt was no stranger to grief; six years earlier, he had lost his wife of 52 years. As it turned out, Van Brunt’s advice was sound. He ordered Rockwell back to the studio: “Get to your easel and paint; it will all work out in the end!”

Rockwell not only took his “medicine,” he made Van Brunt his model. He knew that his friend was musically inclined, active in the community chorus and Boy Scouts, and had served as a drummer boy during the Civil War. Thus was born our Post cover illustration featuring the older musician pondering new beginnings. Notice the poignant sheet music titles clearly on display around him.

Rockwell incorporated another hidden message in the illustration—he was good at that. Look closely at the hatband and see if you can decipher the meaning of the three stylized letters so appropriate to the artist’s predicament.

[Give up? The letters are “WOU”—With Out You.]

Less than six months after the painting was published, Rockwell married a schoolteacher named Mary Barstow with whom he had three sons—Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter.

Classic Covers: Rockwell Behind The Canvas

You know these classic Rockwell paintings, but do you know the details behind them?

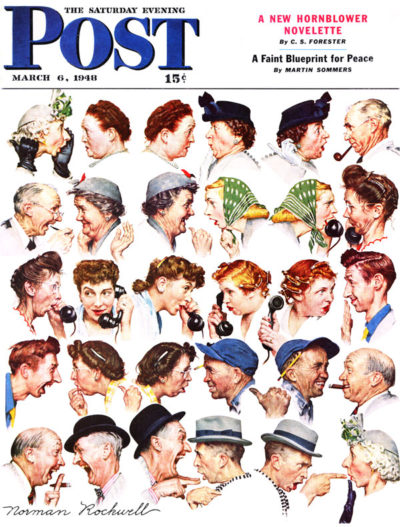

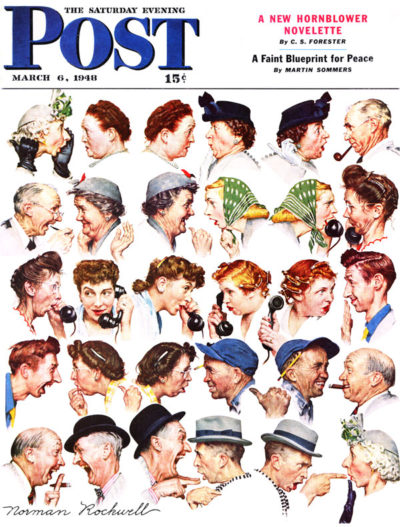

The Gossips—March 6, 1948

It seems Rockwell had a neighbor who started a disagreeable rumor about him. What can one do about a nasty gossip? Well, if you are a famous illustrator, you can paint a cover about it.

It started with just a couple of people, then it just grew, leaving Rockwell in need of more models. The result, said the editors, is that we see “almost the entire adult population of Arlington, Vermont.” As he worked on the project, the artist worried that his friends and neighbors might be offended, so he included his wife and himself. Mary Rockwell is second and third in the third row, spreading the rumor via rotary phone. In the gray felt hat in the bottom row is, of course, the artist himself (you can click on the image for a close-up). You’ll notice the lady at the end is the one at the beginning who started the rumor, and our friend Rockwell appears to be giving her a piece of his mind. Apparently, the neighbor who started the rumor in real life never spoke to Rockwell again. I have a feeling it was no great loss. The lesson here is: don’t anger someone whose Saturday Evening Post covers are viewed by millions.

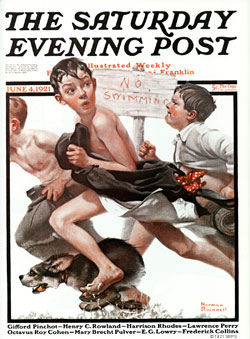

No Swimming—June 4, 1921

These boys sure are hightailing it out of there! Even the dog is hauling tail (okay, sorry). Rockwell expert Robert Berridge wrote about this cover in a recent edition of The Saturday Evening Post magazine. “Franklin Lischke—the freckle-faced lad in the middle,” writes Berridge, was so taken with Rockwell’s work, he ended up studying art himself, becoming a successful commercial artist.

The question remained for decades: what were the boys running from? “Could it have been the pond owner,” Berridge asked, “an irritated bull, or a group of passing girls?” The model himself told Berridge. Answer at the end of this piece…

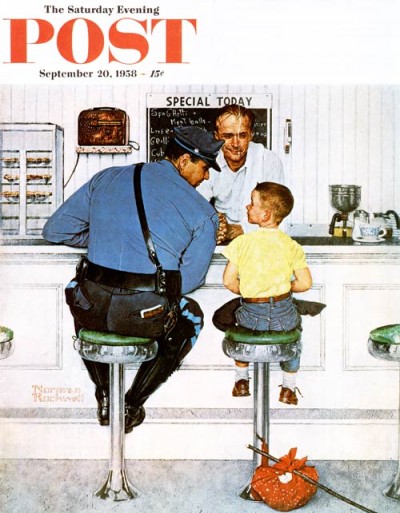

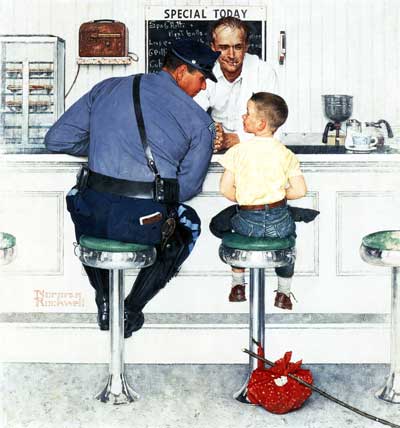

The Runaway—September 20, 1958

“The Runaway” is one of everyone’s favorite Rockwell covers. A neighbor of Rockwell’s, Richard Clemens, just happened to be a Massachusetts State Trooper and gladly posed for the artist, along with young Eddie Lock. After posing for this now iconic cover in 1958, Richard and Eddie didn’t see each other again until 1971 when they happened to find themselves sitting next to each other in an evening class (in logic) at a community college.

Besides the touching contrast between the large man and the little boy, there is a myriad of details Rockwell meticulously included: The old-time radio, the pies in the case, the coffee starting to perk and just turning brown, for example. The artist’s “mania for detail” extends to the stools: they were “spring-loaded,” causing the police officer’s seat to sink lower than boy’s. Even the chrome on the stools reflects the front of the diner.

By the way, the answer to the question of the running boys: why were they desperately trying to flee? They weren’t fearing the land owner or trying to hide their bare bottoms from an unexpected visit by girls; they were fleeing a swarm of bees! Thank you, Robert Berridge, for answering that long-standing question!

Classic Covers: Can You Tell a Rockwell?

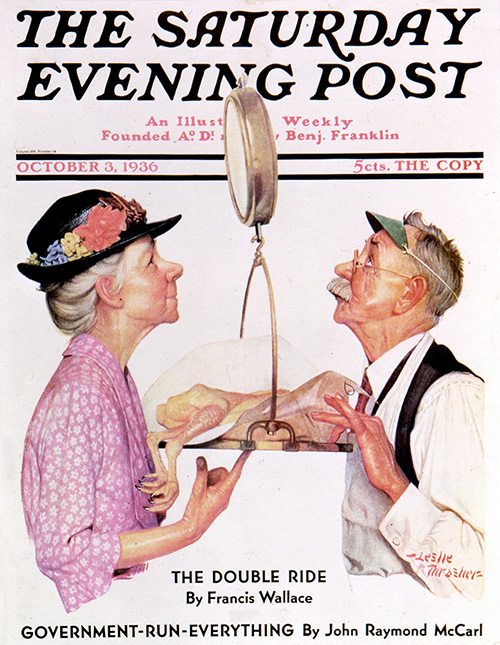

Tipping the Scales by Leslie Thrasher

We’ve used this classic 1936 cover on one of our cookbooks, and people tend to think it’s a Rockwell. Yes, they look like Rockwell-type characters, but no, it isn’t a Rockwell. It was done by artist Leslie Thrasher, who did twenty-five Saturday Evening Post covers. Alas, I’ve had people insist that it was a Rockwell, even though the signature says otherwise. What’s an archivist to do?

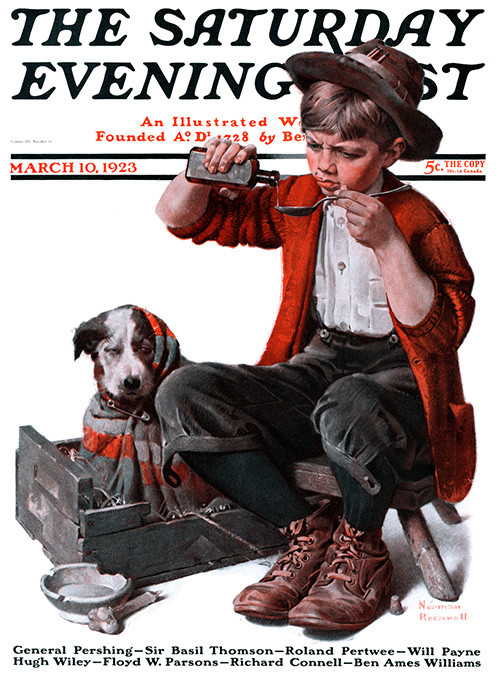

“Sick Pooch” by Russel Sambrook

A surprising number of people think all Saturday Evening Post covers were by Rockwell. That’s kind of like thinking all classical music was composed by Beethoven. Although Norman was a prodigious worker and quite prolific, it would have been a physical impossibility to come up with the thousands of weekly covers that would have involved. A couple of things hint to me that this is not a Rockwell. The boy is too dapper for one. Rockwell liked weather-beaten clothing, especially hats (except when showing a “dressed-up” occasion). The wagon is clearly homemade, but maybe a little too neat and “unworn”. This was by Russell Sambrook, who only did 4 Post covers. The Rockwell version? See below.

Sick Puppy by Norman Rockwell

Here is Norman Rockwell’s version from 1923. Most artists wouldn’t be inspired by a piece of broken crockery, but a dog dish that was far from perfect was right up Rockwell’s alley. This may have inspired the later version above – note the big safety pin holding the blanket around the dog in both paintings and the expression on the dogs faces – let’s hope they weren’t as ill as they were painted.

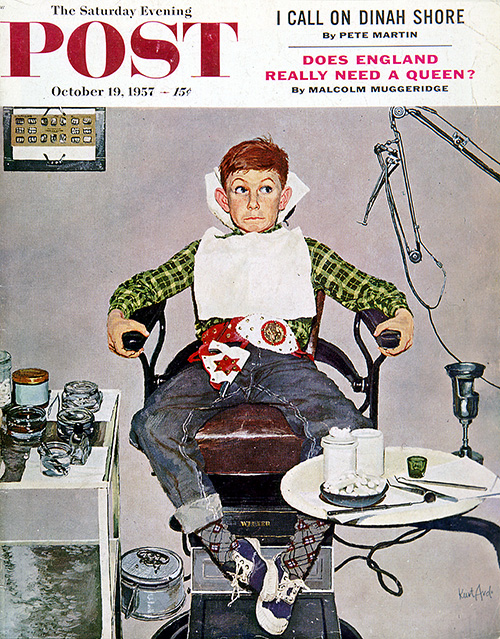

In the Dentist’s Chair by Kurt Ard

Rockwell did great covers of boys, and this one at the dentist’s office…is not one of them. It has the attention to detail (love the socks), the humor and pathos of a Rockwell, but no, it was by Kurt Ard. A reader purchased this, thinking it was a Rockwell because it had been a Post cover. And it did look like Rockwell’s style. If it’s any consolation, having been a Saturday Evening Post cover often adds value to a piece of art, even if not a Rockwell.

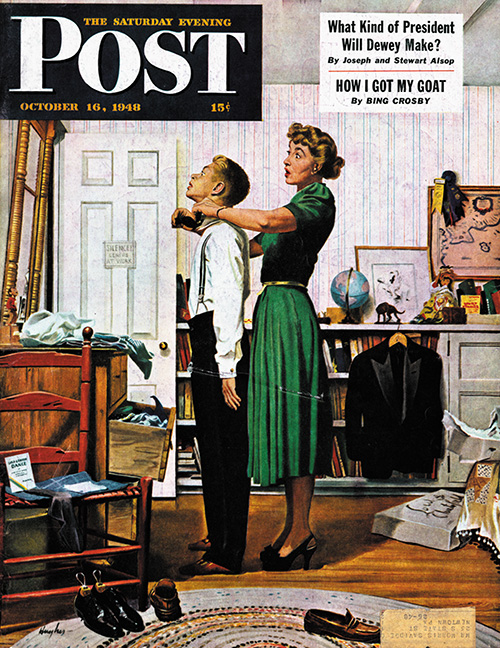

Readying for First Date by George Hughes

There’s more than one reason this cover by artist George Hughes looks like a Rockwell. The models! That young man getting ready for his first date was Tommy Rockwell, son of the artist. And trying to figure out the tie was Mrs. Rockwell. This was even Tommy’s room in Arlington, Vermont. Artists and their families often posed for each other. Who knew better how hard it was to get good models?

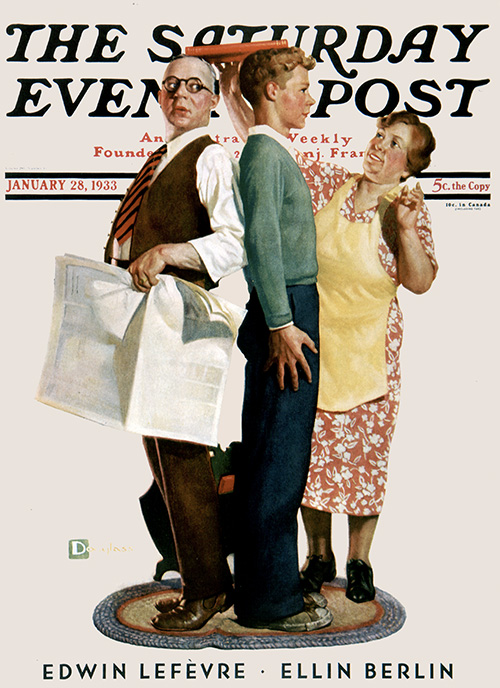

Height Comparison by Douglas Crockwell

Artist Douglass Crockwell did several covers for the Post, including this one. Rockwell-type characters are comparing height from son to dad. As with Rockwell, there is a lot of attention to detail (the pattern in mom’s dress, for example) but it’s a Crockwell, not a Rockwell (sorry – I always wanted to say that). It was hard enough to compete with an artist of Rockwell’s stature, but with the last name Crockwell, it was doubly hard. Poor Douglass Crockwell took to signing his work simply “Douglass”.

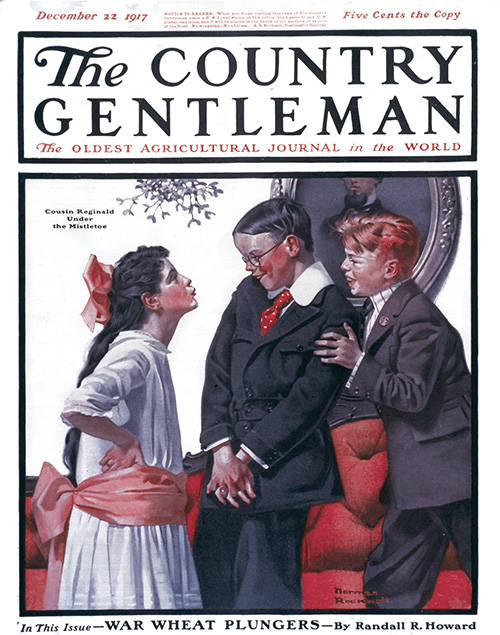

Cousin Reginald Under the Mistletoe by Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell featured a city slicker named Reginald on several Country Gentleman covers (a sister publication to the Post for many years). Here’s an embarrassed Cousin Reginald under the mistletoe from 1917. Compare it to the one below.

Cutting In by Alan Foster

Again, showing the boy in glasses to indicate geekiness. Some of us who wear glasses beg to differ. This was done in 1923 by artist Alan Foster, who did thirty Post covers. As to clues on how to tell the Rockwell from the other artist? In all honesty, sometimes I just have to look at the signature.

Norman Rockwell: America’s Artist

Norman Rockwell didn’t create his celebrated images using only brush and paint. They often took shape first as scenes that Rockwell literally acted out, not only for his editors at the Post, but his real-life models, too. “It was strenuous,” he once explained, “but I felt it was the best way to get across my meaning.” And so he would enthusiastically play out his visions and ideas, a one-man show packed with just the right expressions, giving enough details of each persona in the scene to inspire his models and, more importantly, get his editors to buy his ideas.

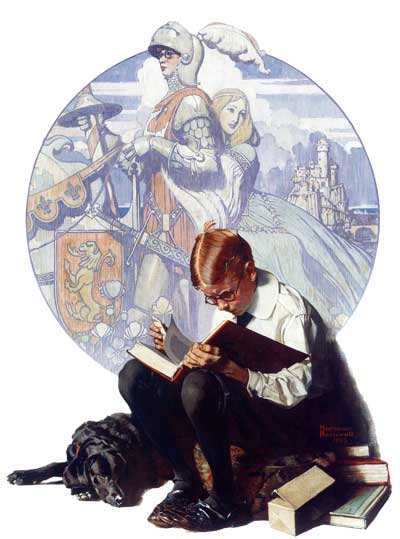

Now, more than 30 years after his death, Rockwell is still acknowledged for deftly chronicling the best of 20th century American life with vignettes of simple emotions evoked by everyday people. This phenomenon is a resounding testament to Rockwell’s prowess as a storyteller and is the subject of another kind of one-man show: the upcoming exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., titled Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. The exhibit, assembled from the private collections of these two popular film directors, will feature rarely viewed pieces of Rockwell’s work, including George Lucas’ favorite, Lands of Enchantment, which shows a youngster imagining himself as an armor-clad knight riding away with a beautiful girl. The point is not the boy reading, but how the book inspires the boy’s imagination, taking him, in idealized form, to another time and place.

“It’s a painting celebrating literature, the magic that happens when you read a story and the story comes alive for you,” notes Lucas.

by Norman Rockwell

November 10, 1923

© SEPS.

And that’s just one of the 50-plus images from the highly anticipated exhibit, which runs from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The exhibit will also explore the artist’s elaborate creative process while spotlighting Rockwell’s ability to capture the range of human expression and distill whole episodes of American life into single and broadly accessible moments by drawing upon a full arsenal of skills that would have served him well as a filmmaker.

According to Virginia Mecklenburg, the museum’s senior curator, both Lucas and Spielberg were inspired by Rockwell’s creativity and tender subject matter, as well as his warm depictions of America without cynicism.

“Both filmmakers grew up in the 1950s, enjoying Rockwell’s illustrations on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post,” says Mecklenburg. “They share the artist’s sensibilities in many ways, and have sought to express similar values, such as loyalty, courage, and friendship, in their own work.”

When working on Star Wars, Lucas said that he realized there needed to be a kind of film that expresses those values, as well as the mythological realities of life—the deeper psychological movements of the way we conduct our lives—that are evident in fairy tales. “Once I got into Star Wars, it struck me that we had lost all that—a whole generation was growing up without fairy tales. You just don’t get them anymore, and that’s the best stuff in the world,” Lucas explains.

Like Lucas, Rockwell was an original. He grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, living in a rough-and-tumble New York boarding house. He quit high school to attend classes at the Art Students League in New York, and was already a working, if occasionally struggling, artist in his teens. But in 1916, when he sold his first cover to the Post, he began to carve what would become a unique niche in the American psyche. Throughout the course of 323 Post covers over the next 50 years, he would stoke and affirm our pride in who and what we are at our very best moments, even if most of us rarely experienced the fresh-faced version of the world.

“Storytelling was very important to Norman Rockwell,” says Lucas. “Every image has either the middle or the end of a story, and you can already see the beginning even though it’s not there. You can see all the missing parts of the story because he took that one frame that sort of tells you everything you need to know.

by Norman Rockwell

September 2, 1939

© 1939 SEPS.

“And, of course, in filmmaking we strive for that. We strive to get images that convey, visually, a lot of information without having to spend a lot of time at it. Norman Rockwell was a master at that—he was a master at telling a story in one frame,” explains Lucas.

That concentration of information as well as emotion is something inherent in Rockwell’s art. Emotion certainly spoke to Steven Spielberg when he first saw one of his favorite Rockwell paintings, High Dive, the August 16, 1947 Post cover that depicts a boy at the top of what must be (or so we imagine from the boy’s expression) a towering diving board. He crouches high above a swimming pool, too afraid to either jump or climb back down. The painting hangs in Spielberg’s office at Amblin Entertainment because it holds a great deal of meaning for the filmmaker.

“That painting spoke to me the second I saw it … and when I was able to buy it, I said, ‘Not only is that going in my collection, but it’s going in my office so I can look at it every day of my life.’ We are all on diving boards hundreds of times during our lives. Taking the plunge or pulling back from the abyss … it is something that we must face. For me, that painting represents every motion picture, just before I commit to directing it—that one moment before I say, ‘Yes, I am going to direct that movie,’ ” says Spielberg.

In the case of his Oscar-winning film Schindler’s List, Spielberg remarked, “I lived on that diving board for 11 years before I eventually took the plunge.”

Even in the creation of their work, Spielberg and Rockwell were more similar than is immediately evident. To create his meticulously detailed recollections of everyday American life, Rockwell worked much like a film director, not just acting out the scenes in his imagination, but scouting locations, casting everyday people from his town for particular parts, choosing costumes and props, and directing his performers to make them instantly familiar to the public. Little wonder then, that filmmakers like Spielberg and Lucas, as well as others, should be so inspired by his work.

In directing his own scenes, Rockwell had a specific focus, just not one based on the stark realism in which he grew up. Instead, Rockwell aimed to depict life in a kind of realistic fantasy. He later remarked in his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, “I paint the world not as it is, but as I would like it to be.”

© SEPS

This desire to “make” the real world a better place, at least in his images, was a sentiment that Rockwell would voice throughout his life. Eventually, he sought something of the idealized world he imagined, when he moved out of the city, first to New Rochelle, New York, then later settling in Vermont with his family. Rockwell found new models in the form of neighbors, as well as his children.

“All of us, my brothers, my mother, and myself, as well as our friends, served as characters in my father’s illustrations at one time or another,” says his son Tom, himself a writer, perhaps best known for his popular children’s book, How to Eat Fried Worms.

A study of Rockwell’s creative process reveals that composing each of his simple-to-understand works wasn’t simply a matter of grabbing whoever was handy and drawing them into a picture. In fact, each image was a highly involved endeavor requiring masterful ability as an illustrator and painter, as well as his unique skill to create “scenes” that would be instantly understood by the viewer.

“Everything I have ever seen or done has gone into my pictures in one way or another. The story of my life is really the story of my pictures and how I made them,” Rockwell said. “I store up things in my mind, and when I need something for a picture—a feeling, a character, a wry smile—there it is. And I draw it out and paint it.”

In the act of describing his work, Rockwell, the artist, embodied his characters, just as his work now embodies aspects of the American character that still strikes a chord, inspiring both other artists and Americans from all walks of life today.

The fact that Rockwell’s canvases are populated with such real-looking people is likely what gives them such resonance, making them believable. Still, there is something in the facial expressions that Rockwell not only captures, but exaggerates—youthful enthusiasm, boyish eagerness, pride, yearning, determination, and more—that transcends location, time period, and situation and makes the works both easy to connect with and ripe for repeated rediscovery, generation after generation.

In this context, Rockwell becomes as significant as any American artist has ever been, and can arguably be credited not only with recounting the American experience but to a large extent, with constructing the collective “memory” of the good old days that we still yearn for, whether we ever personally experienced them or not.

© SEPS.

Rockwell’s opinion of his work during his life was decidedly more humble, however. Certainly he was conscious of his role in the art world. He was an illustrator, not a modern artist or fine arts painter, and he had to satisfy not only himself, but his clients and audience alike. He needed to create scenes that people would get in a matter of seconds. He had to meet deadlines and stick to magazine proportions. And within those strict parameters, he wanted to convey this sense of idealized life. “I guess I had a bad case of the American nostalgia for the clean, simple country life, as opposed to the complicated world of a city,” he explained.

Rockwell’s insight and anything-but-easy process is itself the subject of a new, in-depth book, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, by author and historian, Ron Schick.

“In order to ensure that every detail was perfect, Rockwell first used models and drew from life. Eventually, though, he switched to photographing his subjects in a variety of poses and with varying props, locations, and models. Every minute detail was deliberate, a means of convincing the viewer that they were eavesdropping,” says Schick, who describes Rockwell as a narrative artist with a Jeffersonian sense of America and its modest, everyday heroes.

“The world needed comfort, something to believe in, and Rockwell gave it to them in a way that people from all walks could understand,” Schick says. Understand, yes, but also be emboldened. The moments of inspiration that the artist captured, the tacit encouragement to move forward and celebrate life with all its challenges, setbacks, and triumphs—these ultimately may be Rockwell’s best legacy.

In a nation with cultures as disparate as ours, that Rockwell consistently managed to find patches of common ground for us to build on is a testament to his enduring work, not only for the generations of Americans who grew up seeing his art when it was new, but for future generations who are seeing Norman Rockwell’s America for the first time.

For more information, check out our Post retrospective Norman Rockwell and American Idealist Art.

Rockwell in Hollywood

His scenes of everyday life have become a symbol for Americana at its best, but Norman Rockwell was a portrait artist as well. He painted both sides of the fence politically: Nixon, LBJ, Goldwater, Humphrey, Eisenhower and Kennedy. But we found some portraits of Hollywood names you might enjoy.

The March 2, 1963, cover was of comedian Jack Benny at the ripe old age of (what else?) 39. Rockwell later noted that he was tempted to ask the famous “miser” if he really kept his money in a basement vault.

Rockwell illustrated for other publications as well, such as Country Gentleman magazine, owned by the same publisher as the Post. This magazine’s Summer 1976 issue boasted a Rockwell portrait of John Wayne, whose “rocklike visage challenges the great faces on Mt. Rushmore,” according to the editors, who added, “but he gets around more.”

The May 24, 1930, cover is not exactly a portrait, but the cowboy the makeup artist is working on is none other than Gary Cooper. “He posed for me in Hollywood for three days and worked as conscientiously as any model I ever had,” Rockwell said, “everybody at the lot was crazy about him, and I could see why.”

The fun and mischievous personality of Bob Hope shines through in the February 13, 1954 cover. Hard to believe Hope agreed to pose the very day he returned from a trip to Europe. Most of us would look drained and dull-eyed after an exhausting journey. Can’t you just hear him quipping, “I just flew in from Europe and boy, are my arms tired!”

Norman Rockwell

March 3, 1963

Norman Rockwell

Summer 1976

Norman Rockwell

May 24, 1930

Norman Rockwell

February 13, 1954

I Know That Face! Rockwell’s Regular Model

Here’s a test for Rockwell fans, do you recognize this man?

Norman Rockwell must have been captivated by the looks of James K. Van Brunt the day he showed up in Rockwell’s studio, pronouncing himself as a bold veteran of Fredericksburg and brave fighter of Indians forces. Standing 5 feet, 2 inches tall with a craggy face, knobby nose, and distinctive mustache, Van Brunt became one of Rockwell’s favorite models — posing for numerous covers. So many, in fact, that Post editors began to complain.

Rockwell eventually told Van Brunt he would no longer be able to use him as a model unless he shaved his mustache. He refused, then returned a couple weeks later and said he would do it for $10, which Rockwell paid. “I guess the notoriety he’d gained from posing for me had overcome his pride in his mustache,” Rockwell said. The result can be seen in The Old Sign Painter from February 6, 1926.

Do you recognize Van Brunt in the following covers?

Norman Rockwell

February 11, 1939

Norman Rockwell

January 31, 1925

Norman Rockwell

October 18, 1924

Norman Rockwell

March 27, 1926

Norman Rockwell

August 14, 1926

Norman Rockwell

August 13, 1927

Norman Rockwell

May 26, 1928

Norman Rockwell

June 23, 1928

Norman Rockwell

January 12, 1929

You Asked: What Would Rockwell Do?

One reader suggests that if Rockwell were alive and illustrating today, he would be painting covers depicting “the insane world of today with technology run amok …” Here’s what we think …

Take a look at Lands of Enchantment from 1923: A lad is reading a thick book with intense concentration, and no wonder—the stories of medieval knights is exciting stuff. Young Eddie, in his imagination (which Rockwell generously supplies in the background), becomes Sir Edward, saving the damsel from … well, whatever dreadful fate he was saving her from.

Today, would Eddie be playing in a video arcade? While the young boy concentrates on the game, maybe Rockwell’s background would show hero Eddie, his knight’s armor replaced by a self-contained, pressurized spacesuit, blasting intergalactic bullies with his Super Laser while racking up an impressive score.

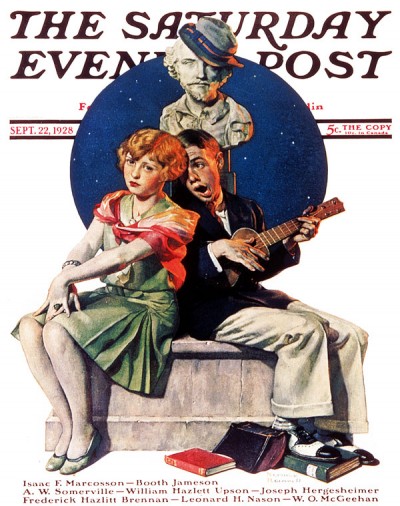

How about the boy serenading the girl from 1928? This is a no-brainer to 2009 Rockwell. On the new cover, the boy would be having his female friend listen to a cool tune on his iPod. It may not seem as romantic, but when you’re 14, this is hot stuff.

And finally, one of our favorite Rockwell covers: The Gossips from 1948. Mabel tells Sue something, Sue tells Jane, who tells George, and so on, and so on. By the time the gossip gets back to Mabel (via Rockwell himself, in the painting), she had a completely different piece of gossip to be shocked over.

Fast forward to 2009: Mabel e-mails Sue about one of the neighbors. “Honestly, that Herman was going out to his mailbox in his robe, which he never bothered to close. Well, he never did have any class.” Sue whips out her cell phone and texts this juicy tidbit to Jane, who Twitters George, and by the time 2009 Rockwell tells the same story back to Mabel, when he ran into her at Starbucks, she is appalled to hear that her neighbor Jim disrobed in the supermarket! An ironic twist (that she will later post on her Facebook page) on the efficiency of technology that Rockwell would have loved. And somehow, we think 2009 Rockwell would have pulled it off.

The Best Rockwell Covers You’ve Never Seen

Think you know all the Norman Rockwell covers for The Saturday Evening Post? Since there were well over 300, probably not. Many of them you’ve seen time and time again, but we’ve dug up some you may have never seen—or if you have, you may have forgotten.

Rockwell’s first cover, which you may not recall seeing unless you’re over 100 years old (and if you are, bless you for finding this on the computer), was the May 20, 1916, The Babysitter. A rather unhappy lad is pushing a baby carriage, while his buddies are off to play baseball. If they would just go play baseball, maybe it wouldn’t have been so bad, but their “see ya, sucker” attitude is a bit much.

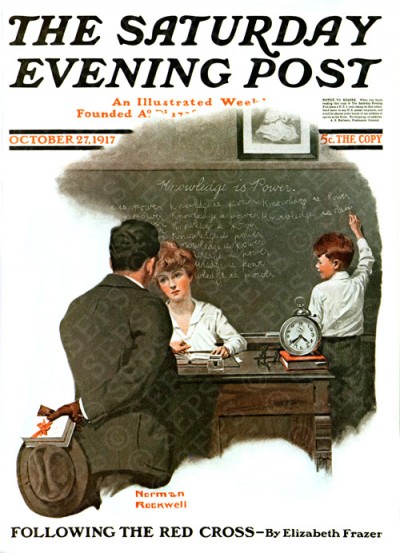

Knowledge Is Power! Another cover we don’t see that much shows us a teacher with a visitor to the classroom. From the look in the schoolmarm’s eyes, we can deduce that it is a very interesting visitor. Little Johnny has to stay late and write “Knowledge Is Power” on the blackboard a zillion times. The student seems to have a different view of that wise saying than the teacher intended.

We had nearly forgotten this one: From 1919 we see a man locking up the office, leaving a note on the door that says, “Gone on Important Business,” the imperative business being that it’s too nice a day to work. The motivational sign over his desk declaring “Do It Now” no doubt refers to playing golf.

Oh sure, you think, come up with covers from 80 or 90 years ago, but what about the ’50s and ’60s—I’ll remember those, smarty. OK, here’s one from 1962: Rockwell visited the John Woodman Higgins Armory Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts (yep, that’s a mouthful), and you’ll need to click on it to see how extremely detailed this painting is. As sometimes happened, the Rockwell imagination went a little off-kilter. The guard taking a lunch break is strictly a Rockwell creation (that wasn’t in the museum), and you have to look very closely to see what else—this is the off-kilter part—the horse underneath that sumptuous armor is watching! OK, we’re not sure if this intrigues us or creeps us out.

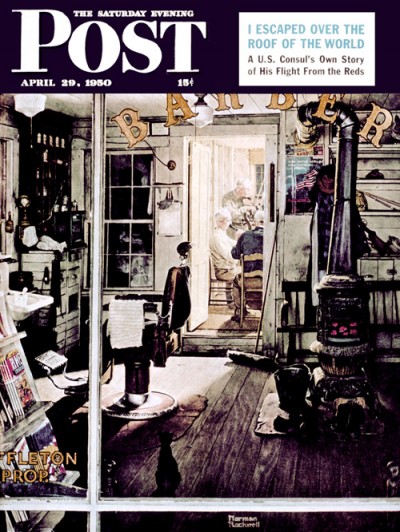

You probably remember Rockwell’s famous barbershop quartet cover, but few remember Shuffleton’s Barbershop from 1950. The charming old place, virtually unchanged from 1907, or so the editors informed us, is also highly detailed from the stove and coal bucket to the minutiae of design on the barber’s chair. But it’s the after-hours peek into the back room that draws us, as the real barber, Rob Shuffleton, trades his scissors and razor for a cello to make music with his buddies. Rockwell told the editors that Rob “is a tonsorial virtuoso who always trims his locks exactly the right length.”

But Rockwell was all about faces, and we would like for you to click on the Christmas 1948 cover: The faces are not only wonderful, they were important faces to Rockwell. They were friends, family, and neighbors. Rockwell liked the cute little pigtailed girl so much, he painted her twice—she was only “twins” on this cover. The lady enthusiastically hugging the young blond man is none other than Mrs. Rockwell, and the young man being welcomed so warmly is their son Jerry. Son Peter Rockwell is to the far left, and the young man in the plaid shirt is son Tommy. There are two famous artists in this cover, and you’ll probably recognize the one with the pipe as Rockwell himself. The delightful grandmother is none other than Rockwell friend, Grandma Moses. May all your homecomings be every bit as joyous.