Ride ‘Em and Weep: Amusement Parks in 1945

In 1945, World War II was ending, G.I.s were returning home, and Americans were ready to put the grim times behind them and have a little fun. Enter the amusement park.

Amusement rides made their debut long before the 1940s. The first rides – merry-go-rounds — have been around since the Roman age of emperors. In the 1600s, the French improved on the idea, developing a carrousel to simulate a jousting match.

The first carrousels appeared in America in the early 1800s, and the first planned amusement park – Playland – opened in Rye, NY, in 1928.

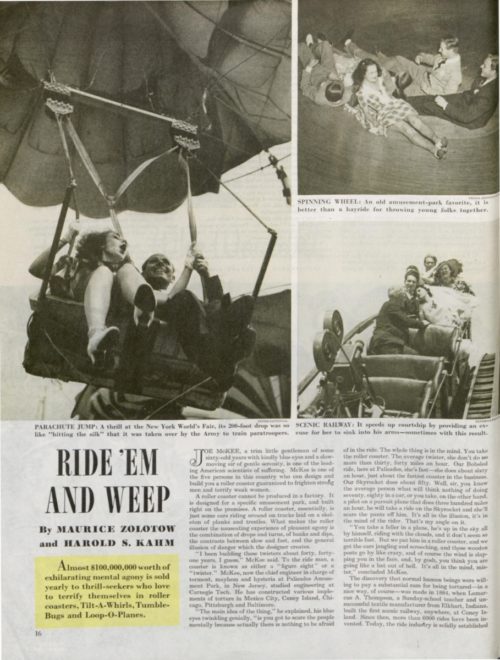

By the 1940s, amusement parks had expanded their offerings to Tilt-A-Whirls, Whips, Dodg’ems, Skooters, Loop-O-Planes, Ferris wheels, and Tumble-Bugs. It was enough of a national trend to appear in an article in the June, 9, 1945, issue of the Post, where the authors interviewed the creators of these scream machines. William Mangels, one of the largest makers of merry-go-rounds, noted that he’d tried using lions, tigers, and giraffes, but people always preferred the horses. Another manufacturer, W.E. Sullivan, owned a bridge company, but nobody bought his bridges. So he started making Ferris wheels, and sold five millions dollars’ worth.

But the real money was in the good old roller coaster – in 1945, one could ride the Thunderbolt, Skyrocket, Zephyr, Mile Sky Chaser, Cyclone, and Giant Racer. While the coasters of the 1940s didn’t nearly match the height, speed, or insane gyrations of modern coasters, they were just as terrifying – maybe even more so for being built upon clattering wooden frames.

In the 1940s, ride makers were still trying to figure out ways to make their coasters faster, scarier, and more stomach-turning. One inventor came up with the Loop-the-Loop, but it didn’t make the cut; at the time it could only move one car at a time around the vertical circle, rendering it unprofitable.

Then, as now, we can’t get enough of rides that terrorize. Why do we love them so much? A psychiatrist of the era said it allowed riders to “experience a pattern of emotions which brings him back to the ‘secure insecurity’ of childhood, and this is one of the sources of the perverse pleasure.”

Sadly, many of the parks mentioned in the article have since closed. Palisades Amusement Park, across the Hudson river on a bluff overlooking New York City, closed 1971. Luxury apartments were built in its place. Pontchartrain Beach outside of New Orleans closed down in 1983. And the Coney Island park mentioned in the article, Steeplechase Park, closed in 1964 (Coney Island is still home to two amusement parks – Luna Park and Deno’s Wonder Wheel Amusement Park).

Amusement parks of the 1940s were no doubt quaint compared to the slick, expensive, immersive parks of today. The authors couldn’t have foreseen what the theme parks would become, or that families would plan week-long vacations and spend thousands of dollars on them. The opening of Disneyland, after all, was still ten years off. But 75 years later, the thrill is still there. As one ride maker observed, “”The new generations are always growing up…and they are always discovering for themselves the same old rides, the same old thrills. No, you can’t ever change that. These rides are as old as gravity.”

Featured image: Geauga Lake Park, Geauga Lake, Ohio (Wikimedia Commons / Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection #77801)

News of the Week: Roller Coasters, Ruined Paella, and a Random Rant about the Weather

Roller Coasters Probably Don’t Cure Kidney Stones

That sounds like Mad Libs, doesn’t it? It’s a headline that seems to just throw random nouns and verbs together. It might as well say, “Pickles Can’t Predict the Stock Market,” or, “Using Sun Tan Lotion Won’t Help You Travel Through Time.” (Side note: You should watch the new time-travel drama Timeless Mondays on NBC. Really fun show.)

But using roller coasters to help deal with kidney stones is actually a real thing. It seems that the jostling your body takes while riding on the amusement park rides might actually help you pass the stones. So instead of an operation, maybe your doctor will tell you to ride a roller coaster three times. (Just pray your kidney stones don’t flare up in the middle of winter when the parks are closed.)

Don’t get too excited yet though. As Slate says, this seems to be one of those specific, fun studies that comes up every other week that we really have to take with a grain of salt (which is something that might lead to kidney stones).

Nobody Likes Jamie Oliver’s Paella

Chef Jamie Oliver’s “Recipe of the Day” quickly became “Controversy of the Day” online. He made a paella and had the audacity to add chorizo to it.

https://twitter.com/jamieoliver/status/783251738509836288

Protestors — yes, there are paella protestors — freaked out on social media and called out Oliver for his “abomination.” It seems that “real” paella has to use certain ingredients, such as Spanish rice, chicken, rabbit, and green beans — and chorizo specifically is not one of them. And for the record, no potatoes, peas, or garlic either.

I don’t know, Oliver’s dish looks pretty good to me.

RIP Richard Trentlage and Rod Temperton

Richard Trentlage was responsible for many classic ad jingles over his long career, including “McDonald’s is your kind of place,” The National Safety Council’s “Buckle up for safety, buckle up,” and V8’s “Wow, it sure doesn’t taste like tomato juice.” But he’s probably best known for this little tune:

It was announced this week that Trentlage had died of congestive heart failure on September 21 at the age of 87.

Rod Temperton passed away in London at the age of 66. He wrote many Michael Jackson songs you know, including “Thriller,” “Off The Wall,” and “Rock with You.” He also wrote Heatwave’s “Boogie Nights” and George Benson’s “Give Me the Night” and wrote songs for Aretha Franklin, Donna Summer, and many others.

Goodbye Carnegie Deli

The Carnegie Deli is closing after 79 years.

Owner Marian Harper says that all of the early mornings and late nights have taken their toll, and it’s time to shut the doors. The famous Manhattan restaurant will close at the end of the year.

Sigh. Yet another legendary institution I didn’t get to experience before it closed. Now, if you want to visit a real classic NYC deli, you’ll be going to Katz’s. But Carnegie actually has a restaurant in Las Vegas too, at The Mirage, and that’s going to stay open.

An Open Letter to All of the Meteorologists I Watch Every Day

Dear Meteorologists,

Can you tell me why you think it’s so interesting that one recent day was the first time since April that the morning temperatures were in the 40s? Did you really expect it to be in the 40s in the summer months of June, July, and August? It’s like you’ve just told us it’s the first time it hit the 40s in 10 years. Now that would be an interesting factoid.

It’s the same thing every June. You’ll breathlessly tell us that it’s the first time the temperature has hit 90 in 182 days or something. Can you believe it?! Yes, I actually can because I don’t expect it to be 90 degrees in October, November, December, January, February, or the early spring months.

Sometimes numbers are just numbers, and they don’t make the weather segment any more exciting.

And the Highest Paid Actor on TV is …

Nope, it’s not Kevin Spacey or Mark Harmon or Kerry Washington or Julia Louis-Dreyfus or any of the voice actors on The Simpsons. Guess again. Come on, give it a shot. Never mind, you’ll never guess, but Variety has the list of the highest paid actors on television, along with what talk show hosts, news anchors, and reality show hosts get paid. The top three actors all come from the same show.

The highest-paid person on TV overall? It’s Judge Judy Sheindlin, who makes $47 million a year.

This Week in History: Peanuts debuts (October 2, 1950)

Charles Schulz drew the strip until the last comic ran on February 12, 2000, just one day after he passed away at the age of 77. Nobody took over for him; the strips you read now are reprints from the past.

Here’s the very first Peanuts comic. That punch line is funny yet also a bit caustic.

This Week in History: The Dick Van Dyke Show premieres (October 3, 1961)

This is my favorite comedy of all-time, and this week marked 55 years since it debuted on CBS. It’s amazing how well the show holds up today. And to think that it was almost canceled after the first season because of low ratings.

Here’s a little curio from the early ’60s: Rob and Laura Petrie doing a commercial for Kent cigarettes on the set of the show.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=KpXHsICG9a8

This Week in History: Soviet Union Launches Sputnik I (October 4, 1957)

The launch of the first satellite spurred the United States into action, leading to our own satellites and the creation of NASA.

National Apple Month

October is the month we celebrate Red Delicious, Gala, Fuji, McIntosh, Empire, Pink Lady, and of course the classic Granny Smith. How ’bout them apples?

Here’s a recipe for Rachel Allen’s Irish Apple Cake, and here’s one for Bacon, Cheddar, and Apple Bake. This Applesauce Cake from Betty Crocker is a great fall dessert to try, and if you want to use apples in something other than a dessert or snack, how about some Apple Stuffed Chicken Breasts?

You could even add some apples to your paella if you want. Just don’t tell anyone on social media about it.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Presidential Debate (October 9)

The second debate between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, will air on many stations starting at 9 p.m. Except for NBC, which is showing the Giants/Packers football game.

Columbus Day (October 10)

Or, if you’re in Denver, you can celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Canadian Thanksgiving (October 10)

Yup, they have Thanksgiving too.

Roller Coasters: When Science Takes You for a Ride

The roller coasters of the 1940s would seem tame to the seasoned thrill-ride passenger of today. But to the authors who wrote the 1945 Post article “Ride ‘Em And Weep,” [PDF] they were marvels of modern science. Engineers had devised rides that would spin, shake, bounce, and drop cars filled with screaming passengers, only to deliver them safely back to earth. They could explain the ‘How,’ but who could explain the ‘Why’? Why did people pay for the privilege of being terrified? Perplexed, the authors consulted a psychiatrist:

The human animal is a perverse creature. Dr. Louis Berg, a psychiatrist who has studied this aspect of personality, points out that we seek not only security but also insecurity.

“From childhood on,” Doctor Berg says, “the human being likes to flirt with danger. Every child likes to be thrown into the air. It will scream in terror, and yet ask you to throw it up again. The child likes to skirt the edge of danger. It is a kind of secure insecurity. And an amusement park ride must always be dangerous and yet safe. This tendency goes so deep that I would call it a “prepotent reflex,” an instinct to seek mild suffering. More people are masochistic than sadistic, really.

“For the adult to go on a roller coaster is for him to experience a pattern of emotions which brings him back to the ‘secure insecurity’ of childhood, and this is one of the sources of the perverse pleasure attached to riding on a roller coaster.”

The greater the perceived risk, then, the greater the pleasure (if you enjoy that sort of thing).

This question of the danger of rides baffles most of the men in the industry. Some of them say that an accident actually booms business. Now and then, a drunk or a youthful bravo stands up in the car as the coaster takes the dip, and is flung out to his death. In some parks, there will be a long line of customers at the ticket office the next day. In other places, business will drop off for weeks afterward until the accident is forgotten.

Amusement parks knew how extremely safe their rides were, but they could never reveal this to customers. Rather, they engineered the ride to increase the perception of danger.

What seems to make the roller coaster the most zestfully dangerous of all rides is that it involves a speedy rising and falling motion, and also that the car is, so to speak, not under any control, but is proceeding by gravitational pull.

The nauseating experience of pleasant agony is the combination of drops and turns, of banks and dips, the contrasts between slow and fast, and the general illusion of danger which the designer creates.

“I been building these twisters about forty, forty-one years, I guess,” [Jim] McKee said. McKee, now the chief engineer in charge of torment, mayhem and hysteria at Palisades Amusement Park, in New Jersey, studied engineering at Carnegie Tech.

“The main idea of the thing,” he explained, his blue eyes twinkling genially, “is you got to scare the people mentally because actually there is nothing to be afraid of in the ride. The whole thing is in the mind. You take the roller coaster. The average twister don’t do no more than thirty, forty miles an hour. Our Bobsled ride, here at Palisades, she’s fast — she does about sixty an hour, just about the fastest coaster in the business. Our Skyrocket does about fifty. Well, sir, you know the average person will think nothing of doing seventy, eighty in a car.

“Or take, on the other hand, a pilot on a pursuit plane that does three hundred miles an hour. He will take a ride on the Skyrocket and she’ll scare the pants off him. It’s all in the illusion. It’s in the mind of the rider. A feller in a plane; he’s up in the sky all by himself, riding with the clouds, and it don’t seem so terrible fast. But we put him in a roller coaster, and we get the cars jangling and screeching, and those wooden posts go by like crazy, and of course the wind is slapping him in the face, and, by gosh, he thinks he is going like a bat out of hell. It’s all in the mind, mister,” concluded McKee.

Engineering has improved greatly since 1945, though. Today, there’s less need for illusion because passengers are moving faster, going farther, riding higher and falling quicker than ever before. The fastest roller coaster moves at more than 125 miles per hour; you don’t need to appeal to riders’ imagined fears when you move that fast. You can find roller coasters that rise 456 feet in the air, or travel over 8,000 feet. And the most challenging rides don’t simply descend at forty-five or sixty degrees, but at 90 degrees. Straight down.

I just understand the appeal. I think there’s something wrong with my “prepotent reflex.”