The Late, Great Robert K. Massie Wrote About American Life

Journalist and historian Robert K. Massie passed away last Monday, December 2nd at 90 years old. Massie was a contributing editor for The Saturday Evening Post throughout the ’60s, writing about international trade, racial integration, and American life. After leaving the Post, Massie focused more on history, and he published biographies of Russian rulers and histories of warships. His book Peter the Great: His Life and World won the Pulitzer Prize in 1981.

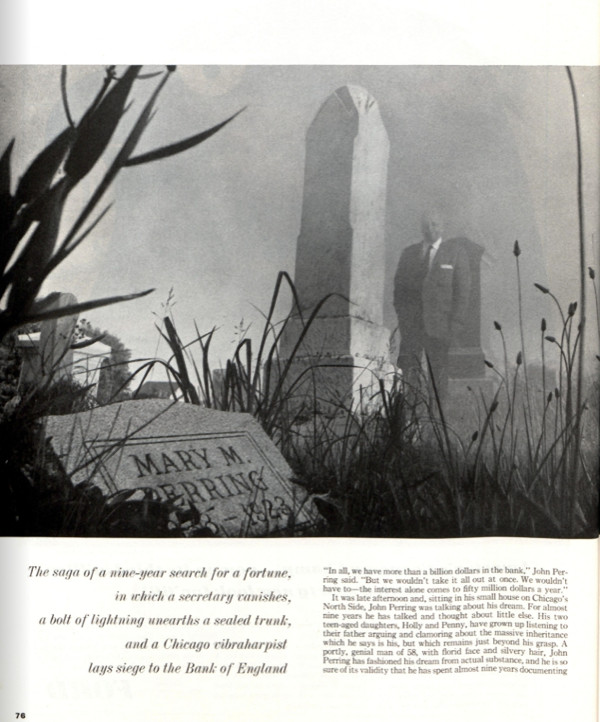

Massie’s feature stories in this magazine spanned a wealth of topics, from gray wolves to Teddy Kennedy to Harlem housing activists. In 1965, Massie followed around a Chicago musician named John Perring who also happened to be fighting the Bank of England for an inheritance he claimed to be more than a billion dollars. Perring’s ancestors had been wealthy merchants, as evidenced by old tax documents he unearthed in Michigan, and several twists and turns during his investigation posed new questions about his supposed inheritance. The story, “Please Send One Billion Dollars,” chronicled Perring’s bizarre, fruitless treasure hunt with thoroughness and detailed storytelling signature to Massie’s work.

Headlines from Robert K. Massie articles that appeared in the Post (©SEPS)

“The Black Coat” by John Galsworthy

Noble Prize winner John Galsworthy was an English novelist and playwright who wrote stories about social grievances of both the upper and lower class. In his short story “The Black Coat,” published in 1926, A Russian general of the Great War reminisces on a past with simpler times. A problem arises when he misplaces his most prized possession.

Published September 11, 1926

The old general, emigre and member of the old time Russian nobility, who had commanded a division in the Great War, sat on a crazy chair before a feeble fire in his garret in the city of Prague. His thin, high shouldered form was crouched forward and his bluish hands extended to what there was of flame, for he was seventy, and his blood thin and cold. It had rained on his way back from the Russian friends whom every Sunday evening he went to see, and his coat was carefully spread out to dry, over the back of his one other crazy chair, before the poor conflagration in the grate.

It was the general’s custom to light a fire on Sunday evenings when it was at all financially possible; the ceremony prolonged, with its apology for warmth, the three hours a week during which he wore the clothes of a gentleman, in the society of gentlefolk. And he would sit before it in his one suit — very old now and white about the seams, but still modish in essence — smoking what of tobacco he had brought away with him and thinking of the past.

The present he never thought of at such times; it did not hear the process, for his present, day by day, consisted in walking before a dustman’s cart, ringing a hell to announce its coming to the inhabitants of the street; and for this he received so little that he was compelled also, to keep soul within body, to wash omnibuses in a garage nearby. These avocations provided him with the rent of his garret and two meals a day; and while engaged in them he wore dingy overalls which had once been blue, and took his two meals at a workman’s café.

On Sundays he stayed in bed till six o’clock, when he would rise, wash and shave himself with slow and meticulous care; then, donning his old black coat and carefully creased trousers, would go forth and walk the two miles to the flat of his friends, where he was sure of a meal and a little wine or vodka, and could talk of the old Russia.

This is what he had been doing for fifty-two weeks in the year during the past five years, and what he counted on doing for the rest of his natural life.

How he gained his living was perfectly well known to his friends, but since it was never spoken of by him, none of them would have considered it decent to mention it. Indeed, on those Sunday evenings there was a tacit agreement not to speak of one’s misfortunes. Old Russia, politics and the spirit of man held the field, together with such other topics as were suitable to a black coat. And not infrequently there would rise, above the ground bass droning through the lives of emigres, the gallantry of laughter. His friends themselves, and all their guests, had the dark cupboards of the outcast and the fallen and gleaming skeletons within them; and so it was essential that neither by word, by manner nor by dress should the existence of an evil fate be admitted.

You might talk of restoration, of redress, of revenge, but of daily need and pressure—no! And in truth there was not much talk of the three R’s; rather did conversation ape normality. And none was so normal as the old general. His was a single mind, a simple face intensely stamped with wrinkles, like the wrigglings in the texture of old pale leather which is stained here and there a little darker by chance misusage. He had folds in the lids over his rimmed brown eyes, a gray mustache clung close round the corners of his bloodless lips, and gray hair grew fairly low still on his square forehead. High-shouldered, he would stand with his head politely inclined, taking in the talk, just as now, before his meager fire, he seemed taking in the purr and flutter of the flames.

After such evenings of talk, indeed, his memory would step with a sort of busy idleness into the past, as might a person in a garden of familiar flowers and trees; and, with the saving instinct of memory, would choose the grateful experiences of a life which, like most soldiers’ lives, had marked a great deal of time and been feverishly active in the intervals. The Czar’s stamp was on his soul; for, after a certain age, no matter what the cataclysm, there can be no real change in the souls of men.

The general might ring his dustman’s bell and wash his casual omnibuses and eat the fare of workmen, but all such daily efforts were as a dream of dismal quality. Only in his black coat, as it were, was he awake. It could be said with truth that all the life he now lived was passed on Sunday evenings between the hours of six and midnight.

And now, with the smoke of his friend’s cigar — for he always brought one away with him; no great shakes, but still a cigar — to lull reality and awaken the past, he smiled faintly, as might some old cat reflecting on a night out, and with all the Russian soul of him savored the moment so paradoxically severed from the present. To go to his lean bed on Sunday nights was ever the last thing he wished to do, and he would put it off and off until the fire was black, and often fall asleep there and wake up in the small hours, shivering.

He had so much that was pleasant in the past to think of every Sunday evening, after those hours spent in his black coat among his own kind had enlivened the soul within him, it was no wonder that he prolonged that séance to the last gasp of warmth.

Tonight he was particularly absent from the present, for a young girl had talked to him who reminded him of an affair he had had in 1880, when he was in garrison in the Don Cossack country. Her name he had forgotten, but not the kisses she had given him in return for nothing but his own; nor the soft, quizzical and confiding expression on her rose-leaf-colored, rather flat-nosed face, nor her eyes like forget-me-nots.

The night his regiment got its orders and he left her — what a night! The fruit trees white with blossom, someone singing, and the moon hanging low on the far side of the wide river. IIeh-heh! The Russian land — the wide, the calm sweet-scented Russian land! And the history that centered round that river, of the Zaporogians — he used to know it well, with his passion for military history, like that of most young men. A scent of nettles, of burdock, of the leaves on young birch trees, seemed mysteriously, conveyed to him in his garret, and he could see lilacs — lilacs and acacias, flowering in front of flat low houses; and the green cupolas of churches, away in the dips of the plain, and the turned earth black. Holy Russia! Ah, and that mare he had of the hook-nosed gypsy at Yekaterinoslaff — he had never seen the equal of her black shining coat — what a jewel of a mare!

The cigar burned his lips and he threw the tiny stump into the ashes. That fire was going out — damp wood. But he had a little petrol from the garage in an old medicine bottle. He would cheer the wood up. His coat wasn’t dry yet — a heavy rain tonight. He got the bottle and sparingly dripped its contents on the smoldering wood; his hand shook nowadays, and he spilled a little. Then he sat down again, and the Burg clock struck twelve. Little flames were creeping out now, little memories creeping to him from them. How those Japanese had fought! And how his men went over the ridge the day he got his cross. A wall — a Russian wall — great fellows! “Lead us, little father, we will take the wood!” And he had led them. Two bullets through his thigh that day, and a wipe on the left shoulder — that was a life!

The crazy chair creaked and he sidled back in it; if one leaned forward, the old chair might break, and that wouldn’t do. No chair to sit on then. A cat’s weight would break down that on which his coat was spread. And he was drowsy now. He would dream nicely, with that fine blaze. A great evening… The young girl had talked — talked — a pretty little hand to kiss! God bless all warmth! … And the general, in his crazy chair, slept, while the fire crept forward on the trickled petrol. From the streets below, too narrow for any car, came up no sound, and through the un-curtained window the stars were bright. Rain must have ceased, frost must be coming. And there was silence in the room, for the general could not snore; his chin was pressed too hard against his chest. He slept like a traveler who has made a long journey. And in the Elysian fields of his past he still walked in his dreams, and saw the flowering, and the flow of waters, the birds and the maidens and the beasts inhabiting.

Two hours passed and he woke up with a sneeze. Something was tickling his nose. Save for starshine it was dark — the fire out. He rose and groped for his matches and a bit of candle. He must be up in time to ring his bell before the dust cart; and, neatly folding his precious trousers, he crept under his two blankets, wrinkling his nose, full of a nasty bitter smell.

A soldier’s habit of waking when he would rang its silent alarm at seven o’clock. Cold! A film of ice had gathered on the water in his cracked ewer. But to precede a dust cart one need not wash too carefully. He had finished and was ready to go forth, when he remembered his black coat. One must fold and put it away with the camphor and dried lavender in the old trunk. He took it hastily from the back of the crazy chair, and his heart stood still. What was this? A great piece of it in the middle of the back, just where the tails were set on, crumbled in his hands — scorched — scorched to tinder! The wreck dangled in his grip like a corpse from a gibbet. His coat his old black coat! Ruined past repair. He stood there quite motionless. It meant — what did it mean? And suddenly, down the leathery yellow of his cheeks, two tears rolled slowly. His old coat, his one coat! In all the weeks of all these years he had never been able to buy a garment, never been able to put by a single stiver. And, dropping the ruined coat, as one might drop the hand of a friend who has played one a dirty trick, he staggered from the room and down the stairs. The smell — that bitter smell! The smell of scorching gone stale!

In front of the dust cart, in his dingy jeans, ringing his bell, he walked through the streets of the old city like a man in a bad dream. In the café he ate his bit of bread and sausage, drank his poor coffee, smoked his one cigarette. His mind refused to dwell on his misfortune. Only when washing an omnibus that evening in the garage he stopped suddenly, as if choked. The smell of the petrol had caught him by the throat — petrol, that had been the ruin of his coat.

So passed that week, and Sunday came. He did not get up at all, but turned his face to the wall instead. He tried his best, but the past would not come to him. It needed the better food, the warming of the little wine, the talk, the scent of tobacco, the sight of friendly faces. And, holding his gray head tight in his hands, he ground his teeth. For only then he realized that he was no longer alive; that all his soul had been in those few Sunday-evening hours, when, within the shelter of his black coat, he refuged in the past. Another, and another week! His friends were all so poor. A soldier of old Russia — a general — wellborn — he made no sign to them; he could not beg and he did not complain. But he had ceased to live, and he knew it, having no longer any past to live for. And something Russian in his soul — something uncompromising and extreme, something which refused to blink fact and went with hand outstretched to meet fate — hardened and grew within him.

The rest is a paragraph from a journal:

The body of an old gray-haired man was taken from the river this morning. The indications point to suicide, and the cast of features would suggest that another Russian émigré has taken fate into his own hands. The body was clothed in trousers, shirt and waistcoat of worn but decent quality; it had no coat.

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: America Invades Russia (100 Years Ago)

100 years ago, America invaded Russia in an effort to cut off the Germans and defeat the Lenin’s Bolsheviks. Find out what happened in this lesser known World War I conflict.

See more History Minute videos.