The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

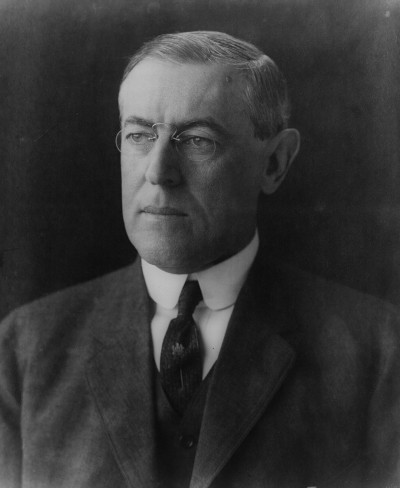

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

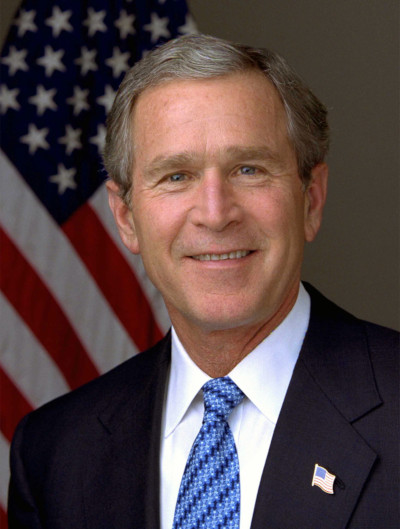

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

News of the Week: Dr. Seuss, Defending Megyn Kelly, and a Day for Fluffernutter

Oh, the Books You’ll Refuse!

What librarian would refuse a donation of Dr. Seuss books? One in Cambridge, Massachusetts, apparently.

In an open letter published in The Horn Book, librarian Liz Phipps Soeiro says that she’s refusing the donation of the books (sent to one school in each state) by First Lady Melania Trump, for a couple of reasons. One, she says that her school and community already have enough book resources. Oh, and second, Dr. Seuss is “a bit of a cliché,” a “tired and worn ambassador for children’s literature,” and that many of his books have “racist propaganda, caricatures, and harmful stereotypes.”

Insert painful sigh here.

While it’s an honest, upfront letter, it’s also a snarky riff against Mrs. Trump’s husband and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. Imagine being so political, wanting to make a point so much, that you drag down the creator of How the Grinch Stole Christmas and The Cat in the Hat. And to think, just a couple of years ago, she loved Dr. Seuss.

I don’t have kids, but when and if I do, I will happily buy them all of the Dr. Seuss books and read them at bedtime. I will not throw them in the trash, I will not sell them for hard cash. I will not hate them here and there, I will not hate them anywhere.

In Defense of Megyn Kelly

Since I’m in the mood to defend people, how about Megyn Kelly?

Oh, I’m not going to completely defend comments she has made in the past or her new morning show, one of the 17 hours of Today programming on NBC every day. Last week’s launch was, well, awkward, from the Jane Fonda interview to the over-the-top congrats from the NBC staff and the “getting to know Megyn” segments that tried way too hard to convince us that she’s a normal human being with feelings and everything (as if anyone doubted that?). It’s early, but she still isn’t a great fit for morning television. The show is a mix of the usual Today fare, Oprah, and The Talk, and Kelly really has to stop it with the weird voices she’s using and the hand gestures (at several points it looked like she was pulling down an invisible curtain).

But I will defend her regarding the most recent controversy. Earlier this week, she had Tom Brokaw on to talk about the shooting in Las Vegas. Brokaw was speaking, and it looked like Kelly cut him off quickly, and some think it might be because he was talking about the National Rifle Association. I watched it live and didn’t think that at all. It just looked like Kelly was out of time and had to wrap up the segment to get to a commercial. But everything now is a conspiracy or negative, and social media went crazy about how “rude” Kelly was and how she cut him off because of where the conversation was going. Several articles were even written about it, including this dumb one at Jezebel and this equally dumb one at The AV Club.

As Brokaw himself explains, the cutoff seemed awkward because he didn’t have an earpiece in his ear and couldn’t hear what Kelly was saying. But I guess the more controversial explanation, the quick “hot take,” is one many people prefer believing.

This Could Be a Dan Brown Novel

J.C. Leyendecker

December 26, 1925

This may seem like an odd story. I mean, how can there be a grave for someone who never existed?

But Santa Claus actually did exist. Oh, maybe not the way we know him now, drawn by Thomas Nast and Norman Rockwell, the ho-ho-ho-ing jolly man at the mall holding up cans of Coke. But Saint Nicholas was a real person, and they may have found his remains in an undamaged grave at the Saint Nicholas Church in Turkey. They found the tomb after surveying the church and noticing gaps underneath it.

So now when your kids ask if Santa Claus is real, you can tell them, “Yes, yes he is! But now he’s dead.”

The 100 Greatest Screenwriters of All-Time

Another day, another internet list we can argue about.

This one is from Vulture, and it gathers several current screenwriters and asks them to pick the greatest screenwriters of all time. The results are, predictably, a mixture of “That’s a great pick!” and “How the heck could you leave ______ out?!?”

No one is going to disagree with people like Billy Wilder (Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard, The Apartment), William Goldman (All The President’s Men, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid), Ernest Lehman (North By Northwest, Sweet Smell of Success), or Preston Sturges (Sullivan’s Travels, The Lady Eve). But I will happily argue about the inclusion of George Lucas, Adam McKay, and Jordan Peele.

I think some of the picks are an attempt to look contemporary (Peele has written two full-length screenplays, for movies that came out in the past year or so), to seem well rounded, to nod to nostalgia, or maybe even to acknowledge to friends. This is what happens to these lists. They’re never based on pure merit.

I’m glad to see Scott Frank and Leigh Brackett on the list. But where are Ben Hecht, Jay Dratler, Robert Riskin, Jules Furthman, and George Axelrod?

RIP Tom Petty, Monty Hall, Anne Jeffreys, Si Newhouse, Richard Pyle, and Jan Triska

Tom Petty had such a string of classic songs it’s hard to list them all, though “Free Fallin” and “American Girl” are good places to start. Petty died Monday at the age of 66.

Monty Hall was one of the great game show hosts of all time, leading Let’s Make a Deal for several decades. He was also a producer on the current CBS version. Hall died Saturday at the age of 96.

Hall was also in one of the best episodes of The Odd Couple:

Anne Jeffreys was a screen and stage actress best known for her work on TV shows like Topper and General Hospital, as well as in movies like Step Lively, Dillinger, and the Dick Tracy films of the 1940s. She died last Wednesday at the age of 94.

For 40 years, Si Newhouse was the Chairman of Condé Nast Publications, which includes magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. He died Sunday at the age of 89.

Richard Pyle was an acclaimed journalist and war correspondent who worked for the Associated Press and was there for many of the big stories over the past several decades. He died last Thursday at the age of 83.

Jan Triska was an actor who appeared in such films as Ragtime, The People vs. Larry Flynt, Ronin, and Apt Pupil, as well as many others. He died Monday at the age of 80.

This Week in History

The Andy Griffith Show Premieres (October 3, 1960)

The show’s Mayberry setting was so realistic that many viewers thought the show was actually filmed in North Carolina, but it was filmed on a Hollywood back lot. The opening where Andy and Opie go fishing? That was filmed near a manmade reservoir in Franklin Canyon Park in Los Angeles. This father and son re-created the opening (Griffith sings the theme song, and yes, it had lyrics):

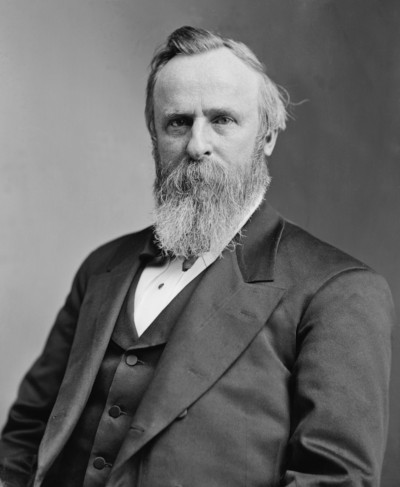

President Rutherford B. Hayes Born (October 4, 1822)

I wonder how the 1876 presidential election would have been covered by today’s media. It was plagued by accusations of intimidation and cheating. On election night, Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden both went to bed thinking they had won, and the election was ultimately decided by a bipartisan commission set up by the House Judiciary Committee. If all that happened today the cable news channels would cover it nonstop, the streets would be filled with protestors on each side, and social media would implode.

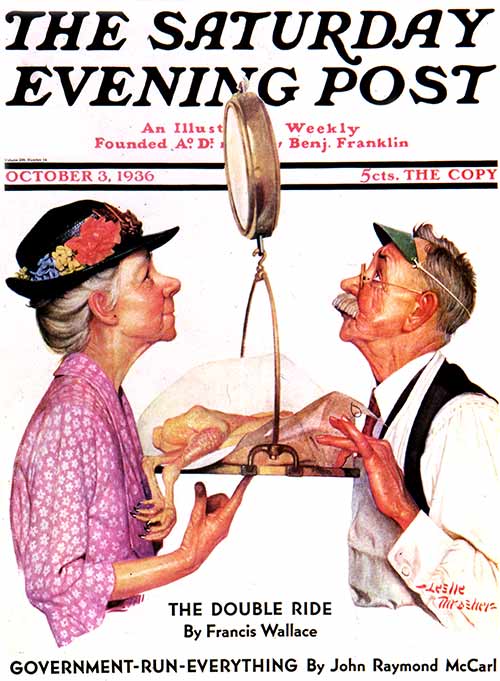

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Tipping the Scales (October 3, 1936)

October 3, 1936

This is one of the most famous covers by artist Leslie Thrasher, who is often compared to Norman Rockwell in his style. There’s a sad back-story to this painting. Two months after the issue came out, a fire at Thrasher’s home destroyed most of his work. Thrasher suffered severe smoke inhalation and eventually died from pneumonia on December 2.

Sunday Is National Fluffernutter Day

The Fluffernutter is a New England thing, but I think it’s also made its way to other parts of the country too. Marshmallow Fluff is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. It was invented in 1917 by a Somerville, Massachusetts, man with the fantastic name Archibald Query. He sold it door to door for a while before selling the recipe to the Durkee Mower candy company. The company came up with the “Fluffernutter” name in 1958 (even if the sandwich itself had already been created by another Massachusetts company in 1918).

It’s pretty simple to make. You take two slices of white bread and spread peanut butter on one side and Marshmallow Fluff on the other. Whether you use creamy or crunchy peanut butter is up to you, though I think creamy is the norm.

I have to admit that even though I’m from New England and still live there, I’ve only had a Fluffernutter once or twice in my life. I never loved it enough to have it more than that. I did often eat white bread covered in sugar though. That was one of my favorite snacks.

Don’t judge me.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Columbus Day (October 9)

Did Christopher Columbus really discover the Americas? While a lot of people credit the Italian explorer — and we have a special day set aside for him — a lot of people credit someone else.

Leif Erikson Day (October 9)

And that other person is Leif Erikson, who did it in the 11th century. So he gets a day too, and that day just happens to be on the same day we celebrate Columbus. That must really irritate both of them.

Of course, there’s a third option, too.

Indigenous Peoples Day (October 9)

When Leif Erikson and Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas, it wasn’t empty — millions of people were already living here — so discover doesn’t really describe what either of these men did. Because of this, four states and a growing number of cities have replaced Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day.

Classic Covers: Children of Invention

You may recall Rutherford B. Hayes’ comment after making the first ever presidential phone call on Alexander Graham Bell’s new telephone. “An amazing invention,” he said, “but who would ever want to use one?”

Our cover artists, quite inventive in their own right, have been chronicling America’s quirky new devices for decades. In observing our reactions to them, they have shown we are all pretty much like kids with new toys (with the exception of Rutherford B. Hayes, that is). It’s the kids, however, who take to the “new” at lightning speed, be it telephones, computers, or e-books. They garner new technologies for their own use, leaving their clueless elders far behind. And kids are inventive, too. But look out when they start thinking they are Henry Ford, the Wright brothers, or Alfred Nobel (inventor of dynamite). Kids in inventor mode, our artists suggest, can sometimes be unsettling.

September 14, 1963

Artist in the Bathtub

August 14, 1950

Space Traveller

November 8, 1952

Learning to Fly

November 8, 1952

Stealing Cake at Grownups Party

September 10, 1960

August 16, 1924

Contributing writer: Joan SerVaas.