A Week Without Seattle

Seattle, long before it became the city of Starbucks and Amazon, was a bastion of union membership. Workers of all stripes were organized into labor groups that comprised a heavy presence in everyday life, and they made history. But you might have to search further than a textbook — or even a city library — to find it.

On the evening of February 6, 25 members of the Seattle Labor Chorus will surround an audience in the atrium of the Museum of History and Industry, singing songs like “Commonwealth of Toil” and “Ship Gonna Sail” and reading dialogue from historic Seattleites like Anna Louise Strong and Ole Hanson. The performance, called Labor Will Feed the People, is a celebration of the legacy of the Seattle General Strike, a labor action that virtually shut down, and seized control of, the city 100 years ago.

When Robert Friedheim wrote, in 1964, about the Seattle General Strike of 1919, he deemed it ultimately harmful to the labor movement of the time since the participating unions’ goals were not accomplished and they appeared to lose a nationwide propaganda war that sparked a Red Scare. If the big strike was such a “public relations disaster for labor,” you wouldn’t know it by the year-long Solidarity Centennial the city has planned to celebrate its impact.

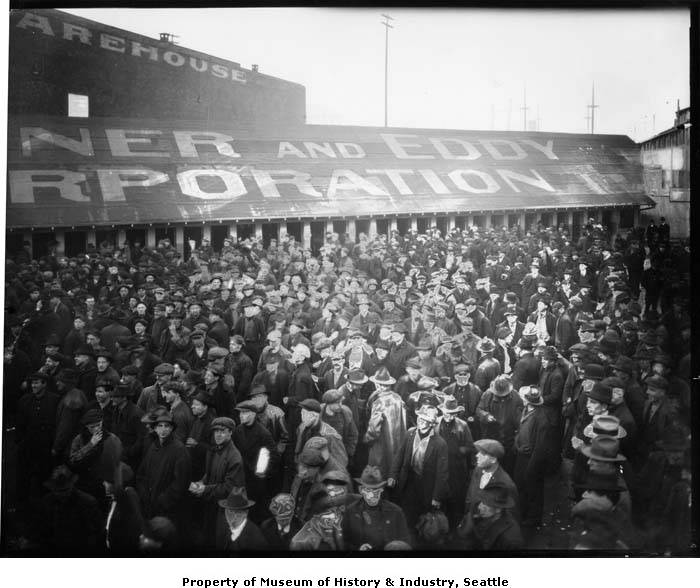

The general strike began 100 years ago today, when around 65,000 workers walked off their jobs. Shipyard workers had already been striking for a few weeks due to their stagnant wages after the war, and laborers in myriad other industries voted to join them. Union membership in Seattle was robust and organized: hotel maids, waitresses, house painters, street car conductors, and many other kinds of workers stood in solidarity with the shipyard workers as members of the Central Labor Council.

The political leanings of strikers ranged from the revolutionary “Wobblies” (Industrial Workers of the World) to more conservative unions, but journalist Anna Louise Strong’s statement in the Union Record on February 4 was widely interpreted as a socialist declaration: “We are undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by LABOR in this country, a move which will lead — NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!” Strong claimed it was not the mere withdrawal of work that would make the strike successful, but rather the ability of the union to maintain the feeding, cleaning, and order of the city: “THIS will move them, for this looks too much like the taking over of POWER by the workers.”

Ole Hanson, the city’s mayor, was initially receptive to the unions, but he quickly took to newspapers near and far to stoke fears of the strikers as anti-American Bolsheviks. He brought in thousands of “special deputies” to the city, raising expectations for violence. Hanson proclaimed on the second day that if the strike didn’t break by February 8 he would declare martial law, which he didn’t actually have the power to do.

“One of the miscalculations by the Central Labor Council was not realizing the fierce backlash that would come from Mayor Hanson and the city’s major newspapers,” says James Gregory, a Professor of History at University of Washington. “The labor movement in Seattle and around the country had many different dimensions. Some of the excitement around the strike came from a left-wing segment that was energized by revolutionary insurgencies happening around the world,” he says, “but most of the strikers were just compelled by an anticipation that organized labor could advance as a responsible participant in decision-making nationwide after being denied that recognition during World War I. There was also a worry that large employers were preparing an ‘open shop’ campaign to try to break unions.”

The Seattle Star printed warnings to strikers to “Stop before it’s too late,” calling the strike a “drastic, disaster-breeding move” and “a test of Americanism.” The general strike came to pass, however, and the CLC organized for the most necessary city functions. Milk stations and kitchens were announced to feed union and non-union families, and drug stores resumed the filling of prescriptions. The CLC organized a welfare committee to provide crucial health and sanitation services and even a law and order committee that dispatched veterans of the war to patrol the streets unarmed.

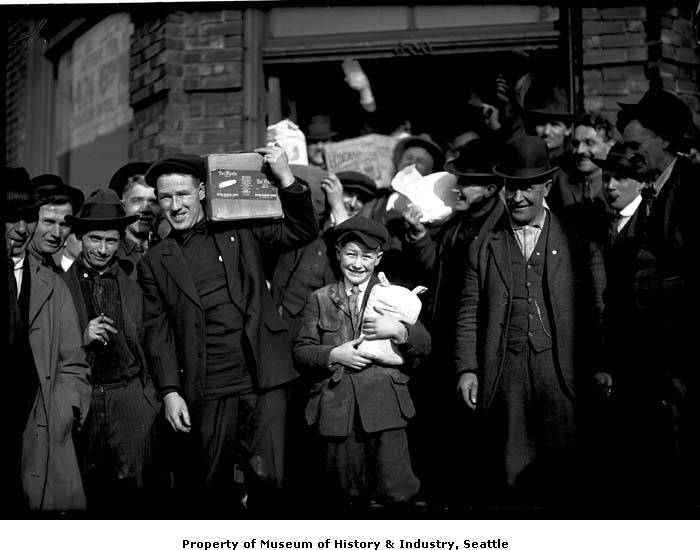

“Nothing moved but the tide,” said longshoreman striker Earl George in reference to the calm of Seattle during the strike. Contrary to the fearful warnings of Mayor Hanson and newspapers around the country, violence did not break out in the city. “It was completely peaceful,” Gregory says. “For the first time a major strike had been conducted without violence or arrests.”

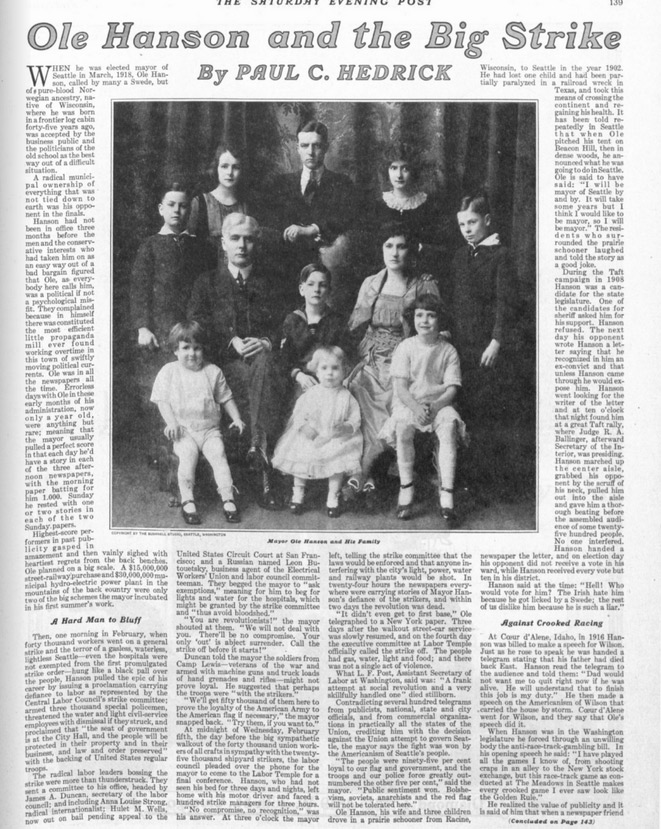

As the days passed, however, the fervor of strikers diminished as they failed to see a desirable outcome. Ole Hanson was regarded nationally as a hero of “Americanism” for standing up to the union’s demands. The general strike ended on February 11, and Hanson — ever the opportunist — resigned as mayor later that year to make a fortune on a national speaking tour. This magazine even printed a glowing profile of Hanson in 1919, praising his hard stance against “radical internationalists” and “syndicalists.”

There were crackdowns on unions and new “open shop” policies throughout the city, and the shipyard workers were no better off. But, according to Professor Gregory, this shouldn’t lead anyone to believe that the strike was an abject failure. In the recently published edition of Robert Friedheim’s 1964 book, The Seattle General Strike, Gregory has written a new introduction to account for a wider assessment of the impact and significance of the action that he says put Seattle on the map. “If you back away from a kind of ‘football score’ assessment, the general strike was very instrumental in encouraging one of the great strike waves in American history,” Gregory says. “The willingness to think as a broad community of labor is what is refreshing and fascinating about this event. We don’t see it much in the culture of individualism in modern life.”

That sense of class community is exactly what playwright Edward Mast has attempted to capture in his play Labor Will Feed the People. He has compiled historical documents and statements from an array of Seattleites to show the diversity of experiences during the strike and to bring to life the spirit of solidarity from 1919.

Mast believes the story of the strike will resonate with a devoted Seattle audience. “In a time of rising inequality that has so great an impact on us, it’s important to look back at a time when working people had a stronger voice,” Mast says. “That there were active labor communities that could make decisions on their own and also contribute to a larger division in this city is something people might miss: when we were organized into units that could collectively make decisions in the interests of justice and equality for the community.”

The performance, and other events in the centennial celebration, will also focus on voices that were left out of the strike, like the African-American, Chinese, and Japanese workers who were largely excluded from the Central Labor Council’s organizing.

Given the depth of the city’s labor history and wide spectrum of progressive politics, Mast is confident about the potential of the event to reach a lively, engaged audience of Seattleites and renew interest in a history that shouldn’t seem so niche. “One of the voices [in the performance] speaks about how wages were not going up as quickly as rent prices were,” he says. “So, as is often the case, there are direct parallels to our immediate experience.”