The Unknown Architect of the Civil Rights Movement

When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.

-Bayard Rustin

In 2013, while awarding a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom to civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, President Obama told a story about the organizer on the day of the 1963 March on Washington:

Early in the morning the day of the March on Washington, the National Mall was far from full, and some in the press were beginning to wonder if the event would be a failure. The march’s chief organizer, Bayard Rustin, didn’t panic. As the story goes, he looked down at a piece of paper, looked back up, and reassured reporters that everything was right on schedule. The only thing those reporters didn’t know was that the papers he was holding were blank.

Obama praised Rustin’s “unshakeable optimism” and “nerves of steel,” crediting him for living a life spent on a march toward equality. But he also recognized that the organizer’s story has been relegated to obscurity because he was openly gay.

Just last month, California governor Gavin Newsom pardoned Bayard Rustin, overturning a 1953 conviction in which he was targeted for “lude vagrancy” and marked a sex offender.

The renewed attention to Rustin’s legacy and unfair treatment comes decades after his death, but it proves the progress that he fought for is closer than ever. As a Quaker, communist, African American, homosexual, pacifist, and leading architect of the civil rights movement, Rustin’s identity and convictions afforded him the perspective to see clearly the country’s societal ills. Unlike Martin Luther King, Jr. or Malcolm X, his contributions to sweeping social justice reform were largely forgotten. Without him, it might not have been possible.

Rustin’s path to activism wound through stints with various radical groups and people. He joined the Young Communist League in 1936, but then severed ties after the Communist Party turned its attention to World War II upon Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Rustin refused to serve in the U.S. military during the war and spent two and a half years in federal prison.

Rustin saw around him people objecting to war and injustice in strokes either too violent and radical or too passive and liberal. He found the perfect mentors in pacifist activists A.J. Muste and Asa Philip Randolph, and he went to work for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. As leaders in the labor movement, Muste and Randolph instilled in Rustin both the importance of nonviolent protest and the power of mass action. He believed these could be used to challenge discriminatory laws and economic inequality that oppressed African Americans.

After organizing the first Freedom Rides on interstate buses in the South in the 1940s (and spending 22 days on a chain gang for his civil disobedience), Rustin traveled to India to meet Mohandas Gandhi. Unfortunately, by the time he made it there, Gandhi had been assassinated. Still, the Mahatma’s teachings on combatting injustice stuck with Rustin as he continued his efforts in the U.S.

Rustin began advising a young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on nonviolent campaigns during the successful Montgomery bus boycott in the ’50s. He had learned about the effectiveness of strikes and boycotts from the labor movement. “Our power is in our ability to make things unworkable,” he said in a speech in 1956. “The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn.”

In 1963, the two worked together again to organize the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. A. Philip Randolph had first conceived of a mass protest in Washington, D.C. for African Americans in 1941, but his event was canceled. With Rustin at the helm, they would attempt to bring thousands of people to the city in the largest demonstration for civil rights in the country’s history.

As the date of the march approached, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond attacked Rustin’s history of “sexual perversion,” draft dodging, and his affiliation with the Communist Party, but King defended Rustin’s invaluable place in the movement. His experience with organizing groups of people for various causes would prove instrumental in the success of the March on Washington.

Video footage from the march shows Bob Dylan and Joan Baez singing “When the Ship Comes In” as Rustin walks behind them, dragging from a cigarette. When he took the stage, Rustin began, “Ladies and gentlemen, the first demand is that we have effective civil rights legislation; no compromise, no filibuster, and that it include public accommodations, decent housing, integrated education, FAPC, and the right to vote. What do you say?” The crowd answered with a thunderous roar. The iconic event gathered more than 200,000 people in the National Mall and permanently altered the struggle for racial justice.

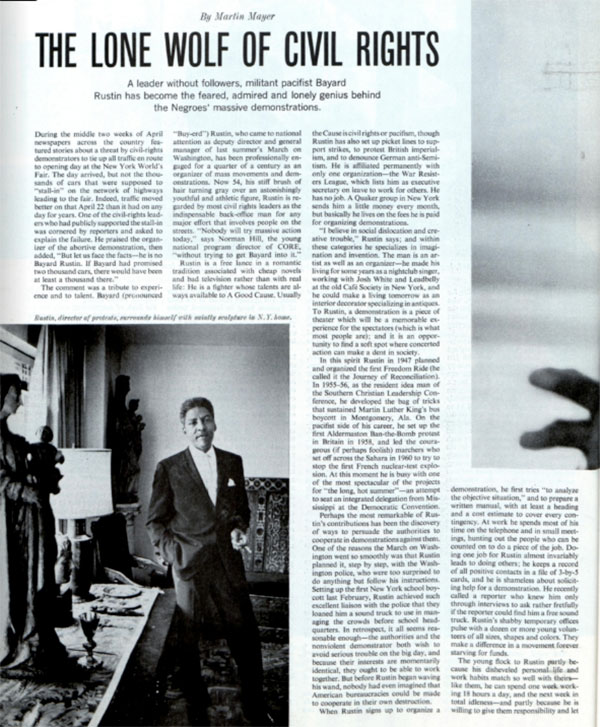

The spring after the March on Washington, this magazine published a profile of Rustin (“The Lone Wolf of Civil Rights”), calling attention to his long career in troublemaking. Rustin was decidedly nonviolent, but his approach to public protest was strictly tied to results: “Rustin insists that every demonstration he runs will be related immediately to a specific objective. Freedom rides and lunch-counter sit-ins are ideal, because they call attention directly to the evil being fought and at the same time establish a strong bargaining position for the negotiations which must be the result of any successful demonstration.”

In the Post’s report, author Martin Mayer notes Rustin’s apparent outsider status in many organizations fighting for civil rights in the ’60s. Mayer claims Rustin’s independence at the time was an organizing strategy or, perhaps, a consequence of his difficult personality, only once mentioning his “morals charge” in California. In hindsight, Rustin’s living openly as a gay man for most of his life (as anyone who met him would attest to) cost him dearly in his relationships and his ability to lead organizations. He broke off with the Fellowship of Reconciliation after several years of defending his sexual orientation to Reverend A.J. Muste, and he faced a short stint of dissociation from Dr. King for fear of sullying the leader’s reputation.

After King was assassinated, Rustin found himself at odds with the more radical Black Power movement (particularly the gun-wielding Black Panthers) as he stayed the course of marrying the civil rights movement to trade unions. Rustin became interested in moving from “protest to politics,” as far as civil rights were concerned, but he took on new issues around the world, like the plights of Soviet Jews and Thai refugees. In a 1986 speech called “From Montgomery to Stonewall,” Rustin drew comparisons between the new gay rights movement and the civil rights movement he had orchestrated:

Our job is not to get those people who dislike us to love us. Nor was our aim in the civil rights movement to get prejudiced white people to love us. Our aim was to try to create the kind of America, legislatively, morally, and psychologically, such that even though some whites continued to hate us, they could not openly manifest that hate. That’s our job today: to control the extent to which people can publicly manifest antigay sentiment.

Rustin died the year after giving that speech to a gay student group at University of Pennsylvania. In it, he assured the students that they must continue fighting for their cause no matter how difficult it was. He said that fighting for legislation was crucial, but noted that often liberation emerged from the culture influenced by the movement itself. “We never got an antilynch law,” he said, “and now we don’t need one.”

Featured image by Bert Shavitz

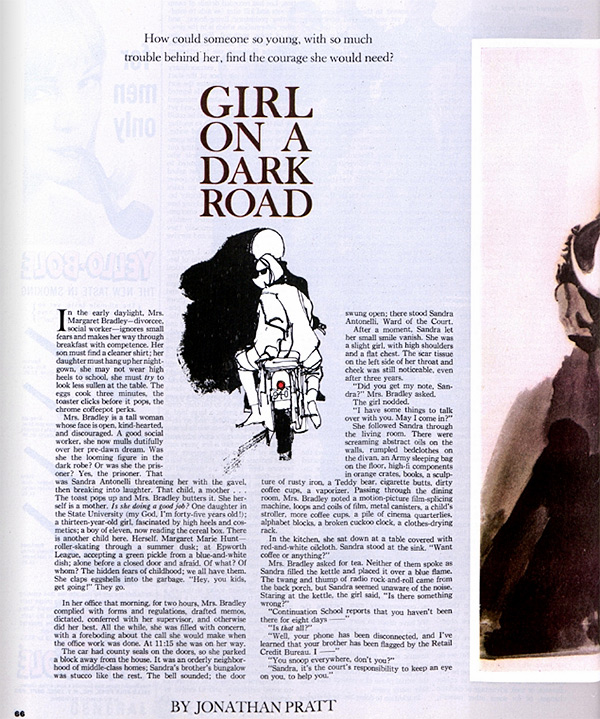

“Girl on a Dark Road” by Jonathan Pratt

Published on December 3, 1966

In the early daylight, Mrs. Margaret Bradley — divorcee, social worker — ignores small fears and makes her way through breakfast with competence. Her son must find a cleaner shirt; her daughter must hang up her nightgown, she may not wear high heels to school, she must try to look less sullen at the table. The eggs cook three minutes, the toaster clicks before it pops, the chrome coffeepot perks.

Mrs. Bradley is a tall woman whose face is open, kind-hearted, and discouraged. A good social worker, she now mulls dutifully over her pre-dawn dream. Was she the looming figure in the dark robe? Or was she the prisoner? Yes, the prisoner. That was Sandra Antonelli threatening her with the gavel, then breaking into laughter. That child, a mother … The toast pops up and Mrs. Bradley butters it. She herself is a mother. Is she doing a good job? One daughter in the State University (my God, I’m forty-five years old!); a thirteen-year-old girl, fascinated by high heels and cosmetics; a boy of eleven, now reading the cereal box. There is another child here. Herself. Margaret Marie Hunt — roller-skating through a summer dusk; at Epworth League, accepting a green pickle from a blue-and-white dish; alone before a closed door and afraid. Of what? Of whom? The hidden fears of childhood; we all have them. She claps eggshells into the garbage. “Hey, you kids, get going!” They go.

In her office that morning, for two hours, Mrs. Bradley complied with forms and regulations, drafted memos, dictated, conferred with her supervisor, and otherwise did her best. All the while, she was filled with concern, with a foreboding about the call she would make when the office work was done. At 11:15 she was on her way.

The car had county seals on the doors, so she parked a block away from the house. It was an orderly neighborhood of middle-class homes; Sandra’s brother’s bungalow was stucco like the rest. The bell sounded; the door swung open; there stood Sandra Antonelli, Ward of the Court.

After a moment, Sandra let her small smile vanish. She was a slight girl, with high shoulders and a flat chest. The scar tissue on the left side of her throat and cheek was still noticeable, even after three years.

“Did you get my note, Sandra?” Mrs. Bradley asked. The girl nodded.

“I have some things to talk over with you. May I come in?”

She followed Sandra through the living room. There were screaming abstract oils on the walls, rumpled bedclothes on the divan, an Army sleeping bag on the floor, high-fi components in orange crates, books, a sculpture of rusty iron, a Teddy bear, cigarette butts, dirty coffee cups, a vaporizer. Passing through the dining room, Mrs. Bradley noted a motion-picture film-splicing machine, loops and coils of film, metal canisters, a child’s stroller, more coffee cups, a pile of cinema quarterlies, alphabet blocks, a broken cuckoo clock, a clothes-drying rack.

In the kitchen, she sat down at a table covered with red-and-white oilcloth. Sandra stood at the sink. “Want coffee or anything?”

Mrs. Bradley asked for tea. Neither of them spoke as Sandra filled the kettle and placed it over a blue flame. The twang and thump of radio rock-and-roll came from the back porch, but Sandra seemed unaware of the noise. Staring at the kettle, the girl said, “Is there something wrong?”

“Continuation School reports that you haven’t been there for eight days —

“Is that all?”

“Well, your phone has been disconnected, and I’ve learned that your brother has been flagged by the Retail Credit Bureau. I — ”

“You snoop everywhere, don’t you?”

“Sandra, it’s the court’s responsibility to keep an eye on you, to help you.”

“Help I don’t need.”

“You’ve been getting it.”

“Money? That goes to Leonard. See Leonard about that.”

“I was hoping Leonard would be here. Did you show him my note?”

Sandra shrugged. She placed two cups on the table, dropped tea bags in them, and poured bubbling water over the bags.

“Sandra, we’re simply making sure that you’re getting along. After the car accident you begged not to be sent back to your aunt and uncle. So we put you in the Group Home.” Mrs. Bradley raised her eyebrows.

“You’re the only one who has ever thrown my baby in my face!” said Sandra with quiet ferocity. “The only one.”

“I’m not throwing the baby in your face, Sandra. You’ve said yourself, many times, that the baby was an accident, a mistake. If we had checked on you more carefully at the Group Home, we might have helped you to avoid that mistake.”

The girl was looking out the window. “You sure conned me out of the baby,” she said slowly. “I’m still thinking about that. Maybe you did me a bad wrong there.”

In silence they sipped tea. At last Mrs. Bradley said, “Sandra, do you remember at the hospital, how you begged to be allowed to live here with your brother’s family?” Sandra stared at her. “Do you realize I went out on a limb for you with my supervisor? That I entered an appeal with the Case Review Board?”

A scowl froze the girl’s plain face, making the scar-tissue seem ugly. Mrs. Bradley stopped herself. “Never mind all that. I gathered you people might be having trouble, so I came out to see if I could help. That’s all.”

“The only trouble we’ve got is you coming around to bug us,” Sandra muttered. She cracked a queer, one-sided smile.

“So? Why have you been out of school?”

“Aw, that’s nothing.” Sandra glanced at the alarm clock on the sill above the sink. “Hey listen! It’s quarter to twelve. I’ve got to go up and cross Caitlin at the boulevard.”

“Caitlin?”

“My niece. One of Leonard and Fay’s kids.”

“Oh yes, of course. May I wait here?”

“Sure.” Sandra tucked the tail of her man’s shirt into her jeans. making herself look thinner and more boyish than ever. “Heat up more tea water if you want.” She walked straight out of the house.

Mrs. Bradley went through the rooms swiftly, her professional eye penetrating the disorder. Two small children sharing the back bedroom; a larger bedroom turned into a cluttered film workshop-and-storeroom filled with complicated-looking equipment; more film stuff in the dining room; Sandra’s brother and his wife sleeping in the living room; Sandra sleeping on the flimsy rear porch, her cot jammed against the laundry tubs. Mrs. Bradley noted the improvised clothes rod, the cheap mirror, the snapshot of a youth on an enormous motorcycle, the plastic radio, the opaque poster paint — orange, blue, green — on the windows instead of curtains. She estimated the square feet of living area, minus the space required for tubs and washing machine — about half the state minimum. And no heat. She looked into the refrigerator, nodding at grapes, carrots, frozen orange juice, frowning at frozen dinners and a bowl of leftover spaghetti. She saw two baskets crammed with unfolded laundry and sniffed them. The things were clean. A moment later, an open, twenty-five-pound sack of dried milk provoked her to say “Good” aloud.

When footsteps sounded on the front porch, Mrs. Bradley was at the kitchen table, pouring hot water over her tea bag. Sandra entered, followed by a five-year-old girl with large, unblinking eyes and a fistful of brightly colored papers. “Say hello to Mrs. Bradley,” Sandra commanded.

The child stared at Mrs. Bradley, at the same time allowing her fist to lay the kindergarten trophies slowly on the kitchen table.

“I expected Leonard home by now,” Sandra said. “You want some lunch?” Mrs. Bradley hesitated, and the girl opened a cupboard. “I’ll just make an extra can of vegetable — ”

Having calculated that she was building rapport with Sandra, that she should watch Sandra in action with her niece, that it would be wise to remain and see Leonard, Mrs. Bradley said casually, “I’d enjoy a little soup.”

At the stove, her back turned, Sandra said, “I’m not missing anything at that school anyway. They’re a bunch of apes over there.” Mrs. Bradley’s heart sank.

Four years earlier it had been simple truancy that started Sandra down a darkening road. Orphaned at thirteen when a highway accident killed her parents, she had been sent to live with a great-aunt and great-uncle, devout evangelicals, in an unimpeachably middle-class suburb. Three months later she was picked up in a stolen car with four boys, truants from a different school. Fishing for understanding, Mrs. Bradley — then recently divorced, recently trained, desperately earnest about this early case — got from the sullen girl only that her great-aunt was a “phony,” that school had always “bugged” her, and that she’d met the four boys “hangin’ around the Laundromat.” Soon after that, another joy ride in another stolen car ended against a telephone pole, and Sandra acquired scars she would never lose. Placed in a welfare agency’s “Group Home” (her great-aunt had declared her absolutely unmanageable), she again dropped out of school, and went farther down the dark road, this time with an older man — there had been a baby that she could not keep.

Now, because things had seemed finally to be working out, Sandra’s absence from school, her sarcasm about it, filled Mrs. Bradley with concern.

“Did I tell you what I’m planning to do?” Sandra asked. “I’m going to be a beautician.”

The girl’s off-center smile commanded a smile in return. Then Mrs. Bradley looked down and moved her cup on the red-and-white squares. “That’s an interesting idea. It might make a splendid long-term project.”

“Long-term nothing,” Sandra snapped. “I start in two weeks. I’m going to Mademoiselle Beauty College out on Listeri, do you know how much a beauty operator can make?”

“A trained, successful beauty operator can earn a good living, I’m sure, but — ”

“You’re against it, aren’t you? Kee-riced. I might have guessed.” The girl pushed her chair back from the table and flung out her thin legs. The child, Caitlin, lowered her eyes to her bowl, as if in modesty, and continued carefully to spoon her soup.

“I’m not against it. Sandra. But you haven’t finished high school. Beauty colleges require a high-school diploma.”

“I’ll go to beauty college in the daytime, see? And night school at night. Before the beauty college is over, I’ll have my diploma, so that’ll be all right.”

“Sandra, you’ll need the diploma before they’ll admit you to beauty college.”

“They’ve already admitted me. The manager is a girl that Leonard used to go with. Clarice. She had a part in one of his films. I’m in, all right.”

Mrs. Bradley covered her eyes with her left hand. She knew about beauty colleges; they figured often in the fantasies of girls with whom she worked. She looked up to find Sandra studying her.

“I get it,” Sandra said. “You think I wouldn’t be any good. You think all beauticians have to be beautiful.”

“I don’t think that.”

“It’s personality that counts. And skill. Mainly skill. I know I can do that work. Anyway, I asked Clarice about my face, whether it would hold me back. She says not if I’m a good technician. Who knows? It might even help in some spooky way.”

“How much is the tuition, Sandra?”

“Three hundred dollars. Leonard’s going to loan it to me.”

Caitlin said, “I want dessert now,” and Sandra told her to get some grapes. The child climbed down from her chair and went to the refrigerator.

“Does Leonard have three hundred dollars?” Mrs. Bradley asked.

“There’s such a thing as credit, you know.”

“Where’s your sister-in-law? You haven’t mentioned her.”

“Fay’s out looking for a job.”

“Is that why you dropped out of school? To take care of the children?”

“Of course.”

“Why didn’t you tell the principal?”

“I’ll tell him when I go back.”

“But Sandra, if you’d made some arrangements, the principal wouldn’t have called me. Your teachers could have given you work to do at home.”

Sandra looked away. “Make arrangements, get permission. That’s too funky. Anyway, I thought I’d only be out a couple days. ‘

“You make things hard for yourself, Sandra. This idea about beauty college — it doesn’t help simply to drop out of school without a word.”

“Then you’re not against that beauty-college scene?”

Mrs. Bradley met the girl’s intent scrutiny. “Some beauty colleges are rackets, Sandra,” she said finally. “I wonder whether they’re being honest with you about your chances. Then there’s the tuition. Is Leonard working now?”

“Of course.”

“Where?”

“On his films.”

Mrs. Bradley’s heart sank again. She had once attended a program of experimental films that included one by Leonard Antonelli. His, like the others, had struck her as beautiful, boring, and repulsive by turns. And disturbing. It was as if her own dreams and nightmares had been spliced into the dreams and nightmares of the people with whom she worked — the delinquent girls, the bureaucrats, the pot smokers, the policemen, school nurses, priests.

Mrs. Bradley remembered now that the admission receipts that night could hardly have paid the rental of the hall, let alone reimbursed the filmmakers. “Sandra, doesn’t Leonard spend more money on his films than he earns from them?” she asked.

“Now, sure. But he’s thinking about the future. He’s — ”

“Is he thinking about the future, Sandra? Leonard is the head of a family. Let’s forget art and the future, and talk about reality now.”

“Aw, you always end up spouting reality.”

“Surely you’re aware of the court’s reluctance to remand you to Leonard’s custody. This is a probationary arrangement

“That fink judge in Small-Claims Court wouldn’t listen. Just because Leonard wouldn’t — ”

“Small-Claims Court?”

Sandra nodded toward the front room. “Here he is. Talk to him.”

Leonard was short and slightly pudgy. A scraggly arc of reddish whiskers looped around his chin, and he wore a scarf inside his open collar. He had come into the kitchen with a three-year-old boy in short pants. The boy’s cheeks were flushed and his eyes looked feverish. Sandra nodded toward Mrs. Bradley and mumbled her name. “Hi.” Leonard said. To Sandra he said, “Infection in both ears. They gave him a shot of penicillin. It hurt, huh, John?”

The child’s mouth began to work, and when Sandra said, “Come here, John,” he rushed to her and pressed his face into her stomach. His sister, Caitlin, moved close, peering to see if he was crying. “Offer him a grape,” Sandra said. When the boy ignored the grape, Caitlin went to the back door and opened it. The radio on the porch blared loudly.

The noise, the sick child, the kindergarten pictures smeared with margarine. the alphabet noodles stranded in her soup bowl. Leonard’s soiled scarf — it all filled Mrs. Bradley with a sudden panic. She pressed her eyelids with her fingertips again.

Sandra warmed up soup for Leonard, they agreed that John should have only broth and crackers, and then Leonard began to berate himself for spending one of Sandra’s welfare checks to buy a better editing device. “I’ve kept track, though,” he whined, thinking it was this that Mrs. Bradley had come to discuss.

It was to this man, Mrs. Bradley thought, that she had implored the judge to award custody of Sandra. She had known that Leonard had been divorced at twenty-one, was suspected of a suicide attempt at twenty-two, had spent years in and out of colleges, had been jailed for an anti-war demonstration; she knew that he went on occasional drinking sprees, that he had been booked recently for brawling with a sculptor over whether a certain obscure poet had fascist tendencies. Now, watching him crush an aspirin with a spoon and mix it into the sick child’s applesauce, watching him lead his son to the bedroom for a nap. Mrs. Bradley remembered that there had been no other place to send Sandra except the detention home.

“Sandra, go and see your principal,” she said. “Right now. Get some assignments from your teachers. No matter what you want to do — beauty college or anything else — you can’t afford to lose this whole semester.”

Sandra changed into a skirt and went off cheerfully, taking Caitlin with her. Leonard, who had returned to the kitchen, sagged into a chair and demanded of Mrs. Bradley, “Remember that old tune When My Baby Smiles at Me?” He whistled several bars. “Well, old John smiled at me just now. The penicillin reached him. Man, we had a rough time around here last night. Fay and I must have gotten up with him about five times.”

“Leonard, I notice the phone’s been disconnected,” Mrs. Bradley said.

“Yeah. We have to go down to the gas station now. Try directing a film sometime without a telephone.”

“Sandra says you’ve been in Small-Claims Court.”

Leonard looked at her in momentary surprise, then concentrated on the soup and leftover bread on the table before him.

“What’s going on, Leonard?”

“It’s simple. We’re broke.” He stood up suddenly, went out to the back porch, and snapped off Sandra’s radio. Returning to the kitchen, he said, “I’ve got to audition a tape. Wait a minute.”

In the living room, he threaded a tape recorder. and a conglomeration of sounds followed him as he rejoined Mrs. Bradley — rising and falling whistles, clanks, rumblings, bells, humming.

“That’s an automated machine shop down on Seventh Street,” Leonard said. “Machines running other machines, correcting their own mistakes.”

“Weird,” said Mrs. Bradley.

Leonard looked pleased.

“Leonard, I do have some things to talk over with you.”

“That’s okay. I can talk and listen at the same time.” He ignored Mrs. Bradley’s wince. “If you want to know something, we’re worse than broke. We’re in the hole. That judgment was nothing. We’ve got a mess of other bills.”

Mrs. Bradley watched him quietly. Was he about to face facts?

“It’ll work out,” Leonard went on. “I’m finishing up a three-thousand-dollar commercial job this week, a sales- training film for Wentworth Pump. It’s finished now, only I’m not satisfied with the pace.”

“Will that clear up your bills?”

“Yeah, sure.” Leonard looked troubled. “Well, not exactly. See, I’m finishing up Part Three of Femur, and there’ve been a lot of processing charges. I promised it to the Association of Film Societies for showings in February. Did you see Parts One and Two of Femur?”

“I’m afraid I haven’t heard of Femur.”

Leonard sighed and stood up. “Let me show you something.”

In the bedroom that was also workshop, storeroom, and office, he showed her racks of prints of his films, booking schedules, and accounts that included back royalties of more than a thousand dollars due from film societies and cinema clubs. “I’ll never collect those,” he said, “but at least the films were seen.” When Mrs Bradley expressed gratification that he seemed organized in a fairly businesslike way, he said, “That’s Fay. She slaves at this stuff.” He showed her clippings and reviews, and she learned that Leonard’s films had won prizes at three film festivals, that he was one of a “handful of outstanding young producers, operating on a shoestring,” and that “foundations are interested in his work.” She asked Leonard about the foundations and he said nothing had happened. They returned to the kitchen.

“I do understand you better now,” Mrs. Bradley said. “Still, my responsibility is Sandra. Sandra has dropped out of school, and the real reason is your money troubles.”

Leonard took off his scarf. His neck looked very scrawny suddenly, and Mrs. Bradley saw in his flat eyes, his slackened facial muscles, his uncertain chin, a very deep fatigue. Nonetheless, she insisted that they lay out his situation in columns of arithmetic. After an hour, taking everything into account, they found that his indebtedness was seventeen hundred dollars. A final payment of four hundred dollars was due from Wentworth Pump, but that had already been attached. In the next two weeks his only certain receipts would be thirty-five dollars from a cinema club and Sandra’s eighty-six-dollar monthly welfare check. Even if Leonard’s wife, Fay, should get a job, most of her salary would have to go to a housekeeper. “Frankly, Leonard, it looks hopeless,” Mrs. Bradley said.

“What’s that? Is that any way for a social worker to talk?” Leonard grinned. “Hell, we’ve been in worse pickles than this. Anyway, let’s get fundamental. You’ve talked to Sandra. Is she sick? Is she underfed?”

Mrs. Bradley didn’t answer.

“Hell no, she isn’t. Sure, we’ve used her welfare check, but is she complaining? Is she?”

“No.”

“Old Sandra’s making it, that’s why. She’s a real existential chick.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I mean that was a mess of chaos she was in. But she kind of — well, made herself, right in the middle of those bad scenes. Now she really is.”

A knock sounded at the front door, and Leonard shouted, “Come in!” A youth in boots, jeans, and a leather jacket strode through the living room into the kitchen, a white cyclist’s helmet under his arm. He had a handsome, thin face and a troubled brow. “Sandra here?”

“Back in a while,” Leonard said.

“The machine’s fixed,” the young man said. He turned and left. From out front came the roar of a motorcycle starting up, then the blats of its violent departure.

Sandra returned, and Leonard excused himself to take a nap. Her teachers and the principal had been okay, Sandra said. They had told her that if she completed enough homework assignments she might yet receive her credits, even if she had to take care of Caitlin and John for the rest of the semester. Encouraged, Mrs. Bradley said she’d try to arrange a transfer to night school next semester. They were about to discuss the beauty college when the youth with the leather jacket and motorcycle helmet returned. His anxious brow seemed to smooth when he saw Sandra. “I got the sprocket.” he said.

“Too much, man,” Sandra said. Standing with her arms crossed before her, she looked down at Mrs. Bradley as if to announce that the interview was over.

Mrs. Bradley introduced herself, and the young man said, “I’m Mike. Pleased-ta-meetcha.”

“I have business to finish with Sandra, Mike. I’d appreciate it very much if you’d leave us in privacy for a few more minutes.”

The boy cringed as if expecting to be struck, a mocking gesture, and then he looked at Sandra, who nodded toward the front door. He clomped out.

“Why do you hate him?” Sandra raged as the door closed. “What’s he done to you?”

Mrs. Bradley stared in amazement.

“He’s not a punk, y’hear? He’s a warehouseman, a union warehouseman. He makes a hundred and eight dollars a week. You can’t tell me who to go out with! I’ll go out with anybody I damn please!”

“Sandra! Of course! I have nothing against that boy.”

How did I provoke that? Mrs. Bradley asked herself as the girl glared. It was true that Sandra’s baby had been fathered by a married, thirty-year-old motorcycle mechanic. (He had made her drunk, but she had insisted that the responsibility was hers.) Well, Sandra obviously didn’t blame it all on motorcycles, as Mrs. Bradley now realized she had done.

“Perhaps I do have a prejudice,” she said. “Motorcycles frighten me. The riders don’t seem interested in control.”

“You ever been on a motorcycle?”

“No.”

Sandra shrugged. There was a long silence, then the girl sat down at the table again.

“Sandra, do you see a lot of Mike?”

“Enough. He wants to get married.”

What’s she got? thought Mrs. Bradley. Skinny, young, plain. And disfigured besides.

“Do you want to marry him?”

Sandra shook her head.

“Why not?”

Sandra looked out the kitchen window, from which Caitlin could be seen playing hopscotch in the driveway next door. “Did you watch Leonard with the kids?” she said. “Those kids have changed him. He used to be a mess, a real kook. Now he works like crazy. You know what he told me? He said, ‘The main thing is, Fay and I wanted Caitlin and John, we tried to have them. So now we realize we’ve got to take care of them, and doing everything for kids makes you automatically sort of love ’em. And when you realize you love your kids, then you begin to like yourself more.’ It’s like church, Leonard says. If there’s anything at all in going to church, it’s because you spend a whole hour in there, and they set it up so you think good thoughts most of the time, and then you’re amazed you could do it, even just that long, and you feel better about everything.”

Mrs. Bradley, moved, was blinking away tears, but Sandra hadn’t noticed.

“It happens to me, even,” the girl said, “just puttering around the house here with those kids.”

Mrs. Bradley was silent for a moment, and then she smiled. “I think I know what your brother means,” she said. “But from what you’ve just told me, I should think you’d want to get married.”

Sandra shrugged. “Mike’s just a friend. We do things together, that’s all, and I like riding the bike. But I don’t want to get married, not until some guy really made me feel like rinsing diapers and all that.”

She stood up. “Fay’ll be home soon, all pooped out,” she said, and began carrying dirty dishes to the sink.

Mrs. Bradley opened the car door and sat for a moment on the end of the front seat, her feet on the pavement. Then she lifted her feet inside the car, and slammed the door. She sat quite still, conscious of the county seals on the car doors, of the official state license plates. I ought to feel secure, she thought, and tried to consider what she would report. The angry snarl of a motorcycle distracted her, and in the mirror she saw the machine slant from around the corner behind her. Accelerating smartly, it whipped past her and on down the block. Sandra, riding sidesaddle, clung to the goggled and helmeted rider. At the intersection, the motorcycle’s brake light glowed red for a few seconds; then the bike banked around the corner and was gone.

Automatically, Mrs. Bradley analyzed the depression that swept over her. She felt old and square, of course, and perhaps she feared secretly that her own children might never be as mature as Sandra Antonelli was right now. She sighed, remembering that she must report to her supervisor what she had seen and heard, what she had concluded. What had she concluded? An existential chick? Brother way out? Yes. And both of them quick to bug.

How did it happen? How did a child emerge so strong from so much ugliness? Stress toughens, Mrs. Bradley told herself. And, of course, E.H.E. Her supervisor was always talking about E.H.E. — Early Home Environment, the first five years. She tried to recall what she had learned about Sandra’s parents, but all she could remember was that the mother had been obese, that the father had been a compulsive golfer and a salesman of some kind.

Featured image: Illustration by Joe Cleary, ©SEPS

The First Virtual Reality

Our desire to fully immerse ourselves into another world has given way to strides both spectacular and peculiar in the realm of virtual reality.

In 1981, John Waters’s film Polyester was shown in theaters accompanied by scratch-and-sniff cards that included scents like model airplane glue, roses, and dirty shoes to give the audience a more complete sensory experience of his regressive cinema. In 2016, an episode of the eerie tech-drama Black Mirror depicted two lovers shedding their physical selves and uploading their consciousnesses permanently into a digital simulation of a 1987 beach town.

At the dawn of virtual reality, a multi-sensory experience was presented as a means for teaching, if nothing else.

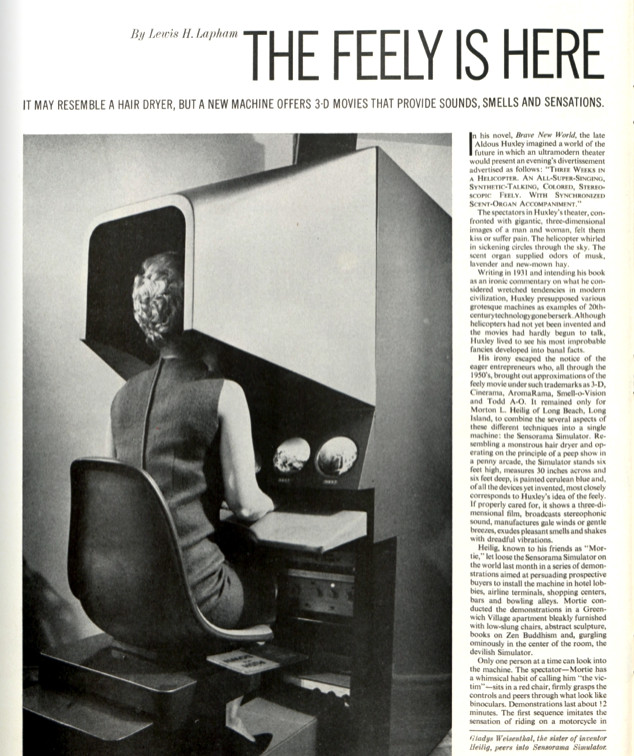

“A basic concept in teaching is that a person will have a greater efficiency of learning if he can actually experience a situation as compared with merely reading about it or listening to a lecture.” That was the reasoning that Morton Heilig gave for inventing the Sensorama Simulator in 1962. His machine resembled a hair dryer from a space age salon, but it was actually an early incarnation of virtual reality technology. After an initial buzz of excitement around Heilig’s invention, the world promptly forgot about him and his innovations.

Heilig’s prototype showed movies that mostly adhered to his instructional vision for the Sensorama, but he needed to make it sexy, too. Literally. One video that he showed in demonstrations featured an exotic belly dancer performing an intimate dance for the viewer. As the spectator watched the three-dimensional video, perfume wafted from the Sensorama any time the dancer gyrated close to the camera. Another video showed a high-speed motorcycle ride through the streets of New York City, complete with wind and diesel smells. Although it wasn’t necessarily functional at training anyone to be a motorcyclist, the experience succeeded at freaking people out.

In 1964, this magazine covered Heilig’s invention, comparing it to the “feely” theater of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The term “virtual reality” would not have been recognizable at the time, so the mysterious futurism of Huxley’s dystopian novel had to suffice to impart the peculiarity of the Sensorama Simulator to Post readers. “Resembling a monstrous hair dryer and operating on the principle of a peep show in a penny arcade, the Simulator stands six feet high, measures 30 inches across and six feet deep, is painted cerulean blue and, of all the devices yet invented, most closely corresponds to Huxley’s idea of the feely,” Lewis Lapham wrote.

The possibilities for the invention, from Heilig’s perspective, were endless. It could be used to train pilots, sell beach vacations, test drive new cars, or just sit at an amusement park, collecting quarters. At the time of the Post’s report, Heilig had attracted the attention of an investor who gave him the ears of executives and entertainment insiders. His Sensorama made it into Universal Studios, Santa Monica pier, and Times Square as an attraction. “3-D, Wide Vision, Stereo Sound, Aromas, Wind, Vibrations” the machine advertised on its front. Thousands of people must have sat in the bucket seat and felt the simulated wind of the Sensorama during its nationwide tour. Unfortunately, the money from a big-time investor never came, and Heilig’s sensory vending machine became a lost oddity.

In 1984, Heilig was interviewed with his invention, and he described the Sensorama’s capabilities proudly, saying, “this was 30 years ago, and now today, there still is nothing as complete as this.” Before Heilig died, in 1997, moves toward virtual reality began to take place, with gaming companies like Sega and Nintendo beginning to release VR systems. Then, “4-D” movies became hit attractions at parks like Six Flags and Disney World. Shows like “Honey, I Shrunk the Audience” and “It’s Tough to Be a Bug!” combined three-dimensional video with animatronics, scents, winds, and other effects to wow audiences and terrify children.

Heilig had worked as a consultant with Disney, supposedly sparking the company’s interest in 3-D video. The technology has been used mostly (even in its 4-D incarnations) to incite thrills and chills, but Heilig had always hoped for more. Speaking to Lewis Lapham for the Post in 1964, Heilig said, “It’s an empathy machine, and if we can develop it right, maybe we can get it to inject feelings of warmth and love.”

These kinds of ambitious results for his high hopes for virtual reality remain to be seen (or smelled).

Featured Image: I.C. Rapoport, 1964

Is the Sexual Revolution Over Yet?

The sexual revolution — or at least some version of it — was televised.

In the 1970 film Zabriskie Point, Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni attempted to capture the collective U.S. sex drive in a series of striking and surreal images: young people engaging in an orgy in the Death Valley dust, explosions of branded domestic items set to Pink Floyd. The film was an utter failure, but it gained cult status and a recent DVD re-release. In hindsight, Zabriskie Point rendered the countercultural zeitgeist of the ’60s boldly and accurately, or, at least, how many have come to imagine the “free love” mythology of the period.

Whether or not dazed hippies frequently made love on mountainsides might be immaterial, because, as it turned out, the revolutionary part was just getting started.

At the time, it seemed as though the whole country might become a bastion of free love and the Pill, with stoned coeds and university feminists declaring a new age (the Age of Aquarius?) in which — perhaps — writhing naked bodies would cover the land from sea to shining sea. But the sexual revolution wasn’t a one-way magic bus ticket to the orgiastic bacchanal portrayed in pop culture and feared by mid-century pearl clutchers. Its effects were actually much more profound.

“The revolutionary part wasn’t necessarily the frequency of sex, but that the factors undergirding sexual activity changed.”

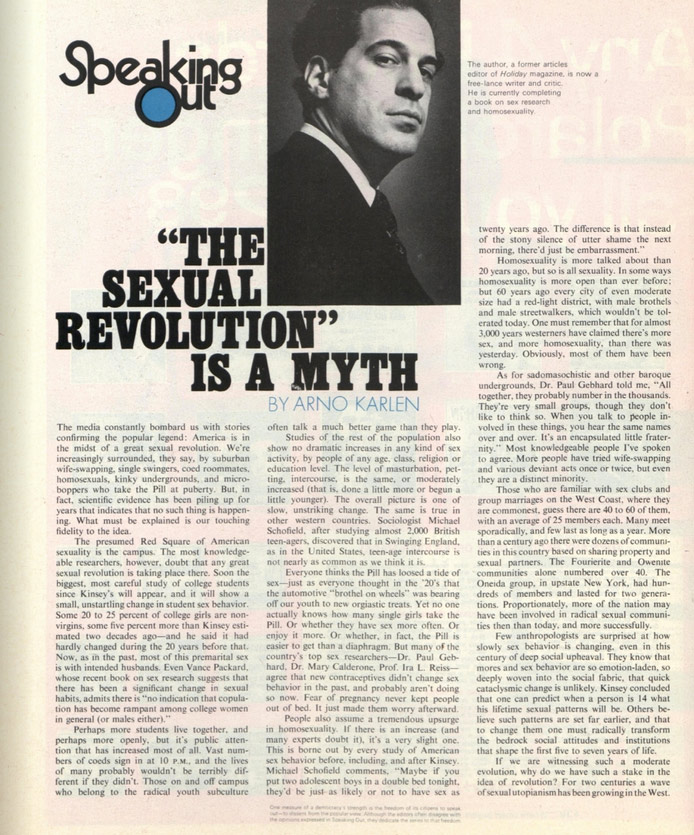

Anyone who was conscious during the ’60s would tell you that the times were a-changin’. The new availability of birth control, reshaping of gender roles, and a burgeoning gay rights movement gave many Americans the idea that the term “revolution,” preceded by the qualifier “sexual,” was an apt characterization of what they saw around them, for better or worse. But it was never about everyone having sex all the time. If that was your goal, then the revolution fell short. At least that’s what future Penthouse editor Arno Karlen thought.

In December of 1968, Karlen took to the pages of The Saturday Evening Post to voice his incredulity of the so-called sexual revolution. Karlen claimed that mounting scientific evidence refuted the existence of a grand American sexual awakening, and he backed it up with studies and statistics.

Karlen’s argument centered on the idea that “four-letter words and mini-skirts don’t mean people act very differently in bed.” In his 1968 article “‘The Sexual Revolution’ Is a Myth,” he cites the humble rise in sexual activity during the sixties (some five percent more of college women were non-virgins), and he poo-poos the effect of the birth control pill, stating that “new contraceptives didn’t change sexual behavior in the past and probably aren’t doing so now.” He also speculates on the unchanging nature of homosexual activity and non-monogamy, or swinging. “I object not to the idea of sexual revolution but to the illusion it has taken place,” Karlen writes. “We need one badly — a real one that will allow people to live healthy, expressive sexual lives without legal penalties and social obstacle courses.”

Karlen believed the sexual revolution was a superficial, media-created non-event of nothing more than slutty outfits and dirty words. The problem is that Karlen came to the party just a bit too early. In 1968, the revolution was just getting started, and mini-skirts were just the beginning.

In his cultural analysis, Karlen might have benefitted from just a few more years of perspective. Six months after the article, the Stonewall riots took place in Greenwich Village. Then, the National Center for Health Statistics found that premarital sex among women had gone from 52 percent occurrence in the early sixties to 72 percent in the early seventies. By 2003, a public health report stated plainly that “Almost all Americans have sex before marrying.”

With a little more time, Karlen might have seen that the revolution did deliver — or at least the social obstacle course of sex before marriage was partly dismantled.

Harvard teacher and history scholar Dr. Nancy Cott says that it’s impossible to discuss the sexual revolution without noting its impact on the concept of marriage in American life. Cott, who has written extensively about issues around gender, relationships, and feminism, and remembers the sexual revolution firsthand, says, “The sexual revolution erased marriage as the bright line between sex that is okay and sex that isn’t okay. It did that legally and socially. That was a major change.”

In the mid-twentieth century, most people would not dare live with a partner out of wedlock. Today, such arrangements are much more common (if not always approved of). “Maybe it’s hard to see how important the presence of marriage was as a social institution, but it was,” Cott says. “Now, maybe you do or don’t marry, or you divorce, and that happens all of the time.” Just around half of U.S. adults are married in recent years, compared with 72 percent in 1960.

Ironically, the same revolution that freed some people from the shackles of marriage allowed other people to put them on for the first time. Dr. Cott wrote several amicus briefs for court cases regarding the same-sex marriage question in the 2000s. While many actors in the sexual revolution deemed the constraints of marriage to be oppressive, Cott says the marriage equality movement was more about civil rights: “You have to be able to opt in to say ‘I am opting out.’”

Another accomplishment of the sexual revolution, according to Cott, was reversing a set of Victorian beliefs that women were sexually dormant until they fell in love with a man who “awakened” their sex drive. “It’s striking to me how long-lasting and deep interpretations have been that women are not as sexually-driven as men.” she says.

Questions surrounding sexuality have long been the focus of Indiana University’s Kinsey Institute, where Dr. Justin Garcia works as an evolutionary biologist and sex researcher. He agrees that the sexual revolution changed the way people approach copulation, saying, “My guess is that more heterosexual couples today are having more conversations about mutual pleasure and consent than 60 years ago. The revolutionary part wasn’t necessarily the frequency of sex, but that the factors undergirding sexual activity changed.”

Garcia, who serves as an advisor to Match.com’s Singles in America study, says that more sex may or may not make people happier, but more consensual, safe, pleasurable sex does.

While we have widespread availability of birth control pills, tacit approval of sex before marriage, and the trend toward communication and mutual pleasure, confoundingly, people seem to be having less sex. Garcia, however, wouldn’t consider it a departure from the arc of the sexual revolution: “In a real sexual revolution, you would expect, perhaps, that sex will only happen when both partners desire it. You might even predict a decrease in frequency if other things are going on, like positive changes in gender egalitarianism,” he says.

The Kinsey Institute researcher claims that one could argue that we’re still in a sexual revolution, since issues around sexual and gender diversity, contraceptives, abortion, and women’s rights are still relevant. “There was a historical moment that we often refer to as the sexual revolution, but, in practical terms we’re still in one. We’re still looking at major shifts in how we understand issues around sexuality and people’s sexual lives and behaviors and how society deals with that,” Garcia says.

To get to the heart of what the sexual revolution means, we need look past the psychedelic-fueled mountainside ménage à trois and into the common sexual desires of everyday people. Non-monogamy and homosexuality existed in America long before the ’60s, and women did experience orgasms prior to the Vietnam War. Our willingness to allow “people to live healthy, expressive sexual lives” is an ongoing national project with unclear beginnings, yet decidedly evident results.

Featured image: Zabriskie Point (1970), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer