Our desire to fully immerse ourselves into another world has given way to strides both spectacular and peculiar in the realm of virtual reality.

In 1981, John Waters’s film Polyester was shown in theaters accompanied by scratch-and-sniff cards that included scents like model airplane glue, roses, and dirty shoes to give the audience a more complete sensory experience of his regressive cinema. In 2016, an episode of the eerie tech-drama Black Mirror depicted two lovers shedding their physical selves and uploading their consciousnesses permanently into a digital simulation of a 1987 beach town.

At the dawn of virtual reality, a multi-sensory experience was presented as a means for teaching, if nothing else.

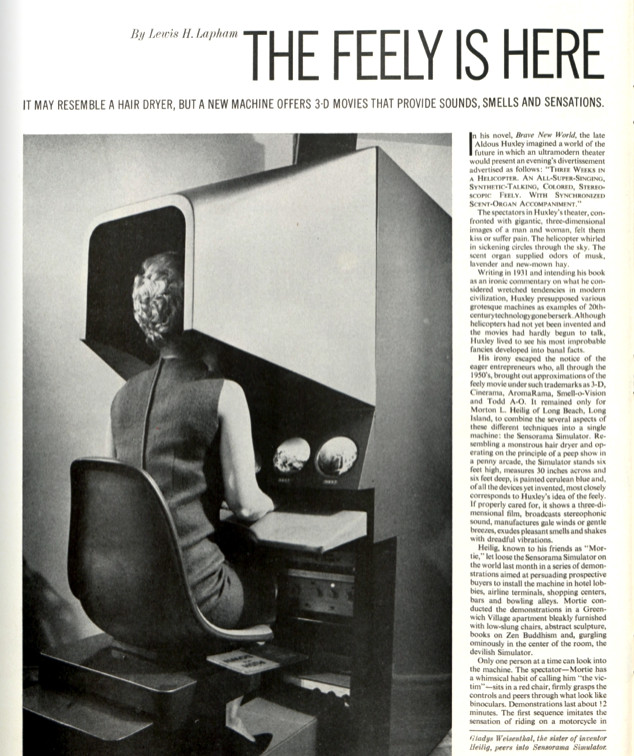

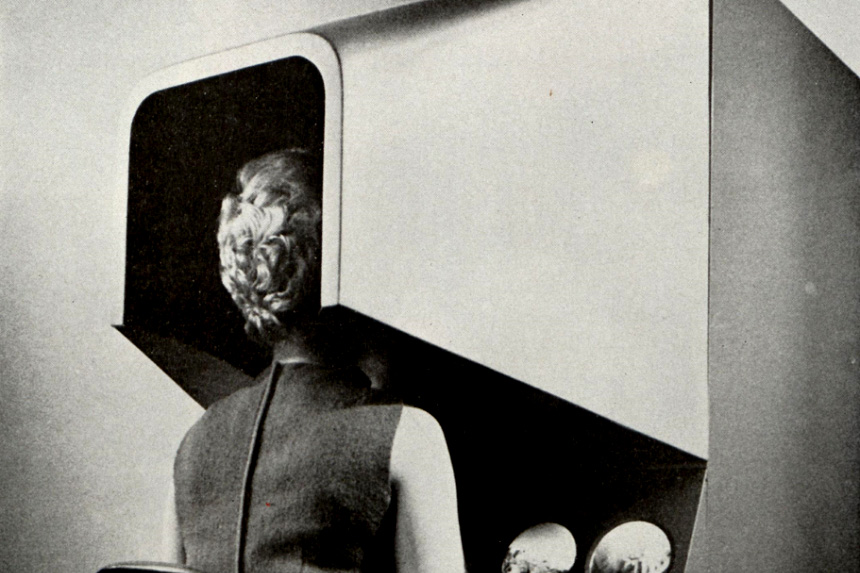

“A basic concept in teaching is that a person will have a greater efficiency of learning if he can actually experience a situation as compared with merely reading about it or listening to a lecture.” That was the reasoning that Morton Heilig gave for inventing the Sensorama Simulator in 1962. His machine resembled a hair dryer from a space age salon, but it was actually an early incarnation of virtual reality technology. After an initial buzz of excitement around Heilig’s invention, the world promptly forgot about him and his innovations.

Heilig’s prototype showed movies that mostly adhered to his instructional vision for the Sensorama, but he needed to make it sexy, too. Literally. One video that he showed in demonstrations featured an exotic belly dancer performing an intimate dance for the viewer. As the spectator watched the three-dimensional video, perfume wafted from the Sensorama any time the dancer gyrated close to the camera. Another video showed a high-speed motorcycle ride through the streets of New York City, complete with wind and diesel smells. Although it wasn’t necessarily functional at training anyone to be a motorcyclist, the experience succeeded at freaking people out.

In 1964, this magazine covered Heilig’s invention, comparing it to the “feely” theater of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The term “virtual reality” would not have been recognizable at the time, so the mysterious futurism of Huxley’s dystopian novel had to suffice to impart the peculiarity of the Sensorama Simulator to Post readers. “Resembling a monstrous hair dryer and operating on the principle of a peep show in a penny arcade, the Simulator stands six feet high, measures 30 inches across and six feet deep, is painted cerulean blue and, of all the devices yet invented, most closely corresponds to Huxley’s idea of the feely,” Lewis Lapham wrote.

The possibilities for the invention, from Heilig’s perspective, were endless. It could be used to train pilots, sell beach vacations, test drive new cars, or just sit at an amusement park, collecting quarters. At the time of the Post’s report, Heilig had attracted the attention of an investor who gave him the ears of executives and entertainment insiders. His Sensorama made it into Universal Studios, Santa Monica pier, and Times Square as an attraction. “3-D, Wide Vision, Stereo Sound, Aromas, Wind, Vibrations” the machine advertised on its front. Thousands of people must have sat in the bucket seat and felt the simulated wind of the Sensorama during its nationwide tour. Unfortunately, the money from a big-time investor never came, and Heilig’s sensory vending machine became a lost oddity.

In 1984, Heilig was interviewed with his invention, and he described the Sensorama’s capabilities proudly, saying, “this was 30 years ago, and now today, there still is nothing as complete as this.” Before Heilig died, in 1997, moves toward virtual reality began to take place, with gaming companies like Sega and Nintendo beginning to release VR systems. Then, “4-D” movies became hit attractions at parks like Six Flags and Disney World. Shows like “Honey, I Shrunk the Audience” and “It’s Tough to Be a Bug!” combined three-dimensional video with animatronics, scents, winds, and other effects to wow audiences and terrify children.

Heilig had worked as a consultant with Disney, supposedly sparking the company’s interest in 3-D video. The technology has been used mostly (even in its 4-D incarnations) to incite thrills and chills, but Heilig had always hoped for more. Speaking to Lewis Lapham for the Post in 1964, Heilig said, “It’s an empathy machine, and if we can develop it right, maybe we can get it to inject feelings of warmth and love.”

These kinds of ambitious results for his high hopes for virtual reality remain to be seen (or smelled).

Featured Image: I.C. Rapoport, 1964

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

A very interesting article Nicholas; this time on the forerunner of virtual reality in the last century’s pinnacle decade. In some ways what we have now is more advanced than what they had then. In others the reverse is true. One thing’s for sure, it’ll be known as something else in 55 years, and other names along the way well before then.