North Country Girl: Chapter 44 — A Narrow, Naked Escape

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

I was tucked up in my old boyfriend Steve’s apartment, drifting along in a haze of pot smoke as the summer slipped by. I roused myself to waitress a few shifts each week at Pracna while Steve’s drug business took off. My roll of ones in the shoebox under the bed grew modestly; when I peeked into Steve’s Folgers can resting on the TV, it was filled to the brim with his unlawful earnings. He had new customers arriving daily and became even more loathe to leave the apartment.

I was reduced to enjoying the great outdoors on Steve’s tiny balcony, no one around except the Land O’Lakes maiden on her billboard. I’d remember another patio, the one in Acapulco, with the blue Pacific to the horizon and the cloudless sky above, broken occasionally by a terrified parasailer. I wondered if I’d ever go back.

The robbers came during one of those twilight Minnesota evenings when the sky is streaks of pink and orange, and the sun hangs out on the horizon as if reluctant to leave the party.

Steve and I were in bed, stoned on very good Thai stick, trying to decide if we should get something to eat or just have another beer. There was a sharp rap at the living room door; the ground floor entrance to the duplex didn’t lock, but opened up to the downstairs neighbors and the stairs to our second floor apartment. Steve got up and pulled on his jeans; we both assumed it was a customer. “Coming?” Steve asked me and I shook my head no. I wrapped the sheet around myself and went to close the bedroom door behind him, when I saw the front door slam open, knocking Steve over as he undid the chain. Two men with guns pushed their way in and stood over Steve.

The guns were huge. As they swung around the living room, the gaping muzzles became the black holes I had learned about in astronomy, an emptiness that could make everything disappear. From the way the guns looked, I realized I was in a badly altered state: my pot buzz was shot through with a sickening bolt of adrenaline that left me rooted to the floor, one eye peering out of the half-inch of cracked door, all my senses reeling. The scene in the living room looked wavy and distorted, as if caught in the fun house mirror at Excelsior Amusement Park.

I knew that behind the two cannon-sized guns were men, but they were indistinct, insignificant forms; the guns were in charge, dragging the men around the room. My stoned brain, weaned on Warner Bros., dredged up a cartoon memory of Yosemite Sam holding a big six-shooter that popped and unfurled a tiny flag with BANG! scrawled in comic sans. I mentally pushed that image aside, it was not helping. But there was nothing I could do to help Steve, who was cowering by the front door, skinny and shirtless and the color of cigarette ash.

I knew that behind the two cannon-sized guns were men, but they were indistinct, insignificant forms; the guns were in charge, dragging the men around the room. My stoned brain, weaned on Warner Bros., dredged up a cartoon memory of Yosemite Sam holding a big six-shooter that popped and unfurled a tiny flag with BANG! scrawled in comic sans. I mentally pushed that image aside, it was not helping. But there was nothing I could do to help Steve, who was cowering by the front door, skinny and shirtless and the color of cigarette ash.

There was yelling; I couldn’t make out what the men were saying. It was if their voices came from far away, like someone shouting down a well. Then I clearly heard “Your stash, asshole! Where’s your stash?”

Steve sat up and made a croaking sound and the guns swung towards him. He was pointing at the glass-top table in front of the couch, the table where Steve’s wares were always on display. “Bullshit!” yelled one of the guns, and swung upward to crack Steve’s forehead. Why wasn’t he bleeding? Steve slowly raised his hand to his head and not till then did red seep through his fingers. He crumpled to the floor while the other gun swept the table drugs into what looked like but surely could not be a Marimekko orange and yellow flowered pillowcase.

My mind finally snapped to attention and my thoughts raced forward. I closed the door softly, but I couldn’t shut out the voices of the men yelling at Steve for drugs and money. The drugs were in the freezer and the money was…in the bedroom with me, in the coffee can perched on top of the TV. The guns knew where there were drugs there was money, and Steve, for all his rugged outdoorsman skills and feigned urban swagger, was about to send them into his bedroom, where I crouched naked behind the door.

I dropped the sheet and dashed out to the patio, which was littered with beer bottles and cigarette butts. I threw one leg and then the other over the balcony rail and dangled over the side, the metal edge cutting into my fingers, my feet scrabbling in the air. It was a pretty big drop from the second floor and I was nude, but the surface twelve feet below me was grass, the scraggly untended lawn that surrounded the duplex. I looked over my right shoulder at the Land o’ Lakes Indian maid, who looked back, as inscrutable as the Mona Lisa, and I let myself drop

I hit hard then clambered to my feet. I ran around to the front entrance and banged on the door of the downstairs neighbors. The young couple who lived there cracked the door, took one look, and hustled me into their front hall where they threw a coat over me. I was scraped up, splotched with grass and dirt, naked and crying and hyperventilating, but they heard me sob “Men and guns and Steve is up there” and the husband picked up the phone to call the police.

Footsteps crashed down the stairs and we all froze. A car started up and sped away. I ran upstairs and found Steve black-eyed and bloodied on the floor. I told him the police were on the way and he began screaming at me then threw himself down the stairs shouting, “Don’t call the police! Don’t call the police!”

The downstairs people were newlywed high school sweethearts from a town down by the Iowa border. He was a serious but dopey-looking med student, she young and pretty with some kind of daytime job that required blouses and skirts and panty hose. We had passed a few words going in and out, introducing ourselves and exchanging pleasantries on the summer weather.

They were always quiet and polite and never mentioned the suspicious characters showing up at Steve’s apartment at all hours or the constant pot smoke in the stairway, nice Minnesotans who minded their own business and didn’t complain, even when their bloodied, roughed-up neighbor was cursing and yelling and his girlfriend was cowering naked underneath the husband’s raincoat.

Somehow Steve and I convinced them not to call the police. Maybe they had had enough excitement for one August night already.

In my version of the break-in, I cast myself as both the damsel in distress and the plucky heroine. In Steve’s version I was the idiot who had almost cost him his Outward Bound scholarship by getting the police involved. I expected Steve to comfort and console me — that could have been me with the black eye! — and then admire my courageous getaway. But Steve was pissed at being robbed and as pissed at me as if it were all my fault. I slammed the bedroom door, kicked the empty Folgers coffee can, and quietly bent down to look under the bed. My shoebox of dollar bills was safely where I had hidden it.

Along with Steve’s stash, the robbers stole away our rekindled romance. Steve was done as a dealer; I guess there was no lesson plan on “Re-Building Your Business After Your Money and Your Drugs Have Been Jacked.” Steve descended into drinking and meanness. He stopped driving me to work, and I started sleeping on the sofa and tried to plan an escape.

Steve and I were slumped together in mutual dislike one night, watching TV, when the phone rang. Steve sighed, braced to disappoint another customer, then handed me the phone. When I hung up, I took a malicious delight in telling Steve, “That was a rich guy I met in Acapulco. He’s flying me down to Chicago for the weekend.” My ticket was paid for, all I had to do was pack my cutest clothes and call a cab to take me to the airport, away from sulking, penniless Steve.

James was waiting at the gate as I stepped off the plane; he swooped me up in an R-rated kiss that scandalized the passengers trying to get around us, then took me out to his gigantic brand new blue and white Cadillac El Dorado that he had just driven off the car lot, priced a few bucks above cost and paid for in cash. I snuggled down into the sweet-smelling, glove-soft white leather seat, but I missed the rented red jeep. This was the biggest damn car I had ever seen; the Cadillac medallion proudly mounted on the hood looked to be about three blocks away. It was like riding around in an ocean liner.

It was a quick drive from O’Hare to James’s place in Des Plaines, a low-rise red brick building that looked an awfully lot like an old U of M dorm. James knew that living in the pokey, middle class suburb of Des Plaines did not go with his man of the world image. He made a point of telling me that the only reason he was there because it was close to the Cadillac dealership where he used to work, but now he was planning to move to downtown Chicago, where the action was.

After the celebratory reunion sex, James asked, “Are you hungry? Do you like deli?” Once I got over the astonishment of James bringing up the subject of food, I said, “I don’t know. What’s a deli?” This delighted James, who couldn’t wait to introduce me to the world of salty, cured meats. We drove to a small bright restaurant filled with older couples eating at formica tables. I was not impressed and I couldn’t identify a thing on the menu outside of the turkey sandwich. James gave his Mephistophelian chuckle and ordered for both of us. That day I became a convert: I slurped tangy beet red borscht, thick with chunks of beef, followed by a plate of salami and eggs with a toasted bagel that I sullied with strawberry jam.

As I washed everything down with my first Cel-Ray tickling my nose like champagne, I spotted Mr. Des Plaines, my old admirer from the Acapulco condo, sitting at a table of alte kakers smoking stogies. He didn’t seem to recognize me with my clothes on. I went back to shoveling it in, emptying the breadbasket of rye slices and Kaiser rolls, and plucking the last cherry pepper from the pickle tray. Knowing James and his eating habits, this might be my only meal for the next twenty-four hours.

James had a whole seductive weekend plan. He had bought a baggie of pot for me, and for himself some coke and Quaaludes, which made for a fun afternoon. James also had dinner reservations for us, which was a shock. In the weeks we had been together in Acapulco, we never had meals that were less than twelve hours apart.

The restaurant, Des Plaines’s finest, wasn’t jet set Acapulco, but anyone from Duluth, Minnesota would have thought it the height of elegance: there were huge brocade covered slabs of menus bound with gilded, tasseled twine (no prices on my menu of course), a fountain with a replica of Brussels’ Manneken Pis tinkling away in the center of the room, and red and white flocked wallpaper which I had not yet realized was more floozy than fancy. The evening wasn’t quite spoiled when the maitre d’ mistook us for father and daughter; we were in Des Plaines, Middle America, after all.

James said, “I want to recreate our first night,” and I felt a little romantic flutter. Once again the steak Diane was set on fire and the Mouton Cadet uncorked. A weird difference crept into our conversation; it turned serious, like a conversation two grown-ups might have.

“I never got to go to college,” James said, leaving unspoken his belief as a self-taught man, he had the best teacher possible. “Tell me about what classes you enjoy the most, how you picked your major.”

My inner nerd stirred from the grave I had buried her in and I launched into why I believed the accepted date for when wandering Asiatic hunters first crossed the Bering Strait to settle the Americas was much too recent, and why a crossing in 10,000 BC was more likely, a topic no one but me and my old girl crush Professor Pearson gave two shits about. James’ eyes glazed over but he managed to look interested for a generous three minutes before launching into his own crackpot ideas on the biological imperative that made men want to screw and women want to breed and how it affected stock prices, that old chestnut about the market rising and falling with skirt lengths. He boasted that his insights into the intersection of sex and economics made him a genius at picking stocks.

I knew that James didn’t go to college because he had been too busy running away from the girl he had impregnated (talk about your biological imperative!). He prided himself on being a self-made man and he had done a hell of a job, making a bundle selling Cadillacs, which he invested in the market, where that money had made even more money.

The wine was finished, James made a trip to the men’s with his vial of coke, came back bright-eyed to order coffee and cognac, and manically jumped into politics and the dastardly deeds of Richard Nixon. We talked and talked, James listening semi-respectfully to my opinions and lecturing me on subjects he thought he was an expert in, until the dirty looks from the busboys became impossible to ignore.

The evening had been romantic, exciting, and unsettling — who was this guy? — and I was ridiculously flattered that James actually wanted to talk to me. Most guys I had been with regarded the first sign of a serious conversation as a cue to stand up and go look for a beer. My tropical romance with James had been flighty, gossamer, a six-week one-night stand; our conversations had been about waterskiing, backgammon, whether James looked fat, the crowd at the Villa Vera, and the latest adventures of the French Canadian girls. I hadn’t had a semi-deep discussion like this since the drug-fueled all nighters in my freshman dorm. But that was with a bunch of still pimply, geeky 18-year-olds, huddled on the floor amid piles of dirty boy laundry. This was in a fancy restaurant with a handsome, sophisticated older man, a man who seemed to be as interested in my mind and my ideas as he was in my young blondness. It felt like a step into adulthood.

North Country Girl: Chapter 43 — Sweet Home, Minnesota

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

There was something about me that triggered a Svengali-like impulse in my older lover James, who had swept me off my feet and into his Acapulco beachfront condo. James loved playing the worldly sophisticate and I was a young sponge, eager to soak up every detail of the kind of life that a year ago I had no idea even existed.

While I did learn to drop that water ski, I never picked up any of the disco dance steps James excelled at (“Do the Hustle!”). James did get me to give up the arm flailing for smooth lifts and shrugs of my shoulders, movements that were occasionally in time with the music. He taught me the complicated economics of tipping: who, when, and how much; we lived in bars, clubs, and restaurants where we never had to wait for a table and drinks appeared and were replaced as if by magic.

After one raised eyebrow from James I stopped ordering White Russians before dinner, and even after. James instructed me to slowly sip the Remy Martin he always finished with, and it was fun sticking my whole face in those enormous snifters. When we dined out, James asked me what I would like to eat and then ordered it for me while I smiled and blinked at the waiter like a deaf mute. James taught me how to do the New York Times crossword puzzle and to play backgammon, and I quickly became better at both of these than he was, though neither of us would admit it. I was always a penny ante gambler: if I lost five dollars at backgammon I felt a pang in my stomach; that five dollars could have bought an economy-size box of the frozen fish sticks I survived on a year ago.

James believed that it was gauche to wear anything less than 18 karat gold; his own heavy chain was 22 karat. One afternoon, he led me into a chic boutique across from his condo, where he ordered a custom-made piece of jewelry, not another chain for himself but a necklace for me. That year, all the girls in Acapulco wore gold pendants spelling out their names. James got off cheap buying only three letters, and in that time and place I could wear GAY around my neck without too many double takes and annoying comments.

To my pleasure and amazement, I had a man buying me jewelry in an elegant store, even if I did end up with the least expensive piece possible. While James was consulting with the saleswoman on the right font and chain for my necklace, I was eyeballing the display of uncut emerald rings and hoping one of them might be in my future. A ring with even the smallest uncut emerald would still make me inordinately happy.

It was a wonderful dream I never wanted to wake up from, but my time in Mexico with James was coming to an end. May is the start of the rainy season in Acapulco, the end of the party season. The lease was up on the apartment and the rented jeep; James was headed back to Chicago. The French Canadian girls had vanished; I hope they all landed wealthy fiancés. The crowds had thinned out at Armando’s and Carlos’N Charlies. Even Fito was leaving, Jorge told me, for a gig in Mexico City.

I checked my bankroll of Pracna one dollar bills; it was almost the same size as it had been when I stepped off the plane. When I was with James, I never had to carry anything in my purse besides lipstick and a comb. I had more than enough to fly back to Minneapolis and keep me going till I figured out what was going to happen next.

James and I had our last dinner at Carlos‘N Charlie’s, our last dance at Armando’s, and did our “Wow, it’s been great” farewells. Then to my surprise, James asked for my phone number. My number? I had no idea of where I would be living; I could have given him my mother’s phone, but my gut said no. James scribbled his number on a piece of paper, told me to call him, and we kissed, a kiss that did not feel like goodbye.

I had no idea what I was going to do back in Minneapolis. I was counting on Pracna to hire me back; no one had been mad that I left with literally no notice, and with the return of summer I knew the place would be swamped with customers. But where could I live?

Even if she had kept our crappy apartment, I could not ask Liz to take me back; I had proved to be the most unreliable of roommates. Mindy and Patti shared a tiny studio that was barely big enough for the two of them. Eduardo had that big apartment, but it would have been weird to ask to stay there whether he was back with Patti or not. And for all I knew, Eduardo might have finally received his academic walking papers and be off at another, more lenient, college, or he could be back home in Miami, being force fed mondongo.

I got off the plane in Minneapolis, went to a pay phone, and stayed there pumping the same quarter in again and again until my old boyfriend Steve finally answered his phone. By a miracle, I had caught him on his last day in the Middlebrook dorm. He gave me the address of his new place and said he would meet me there.

Once again I stood outside a guy’s apartment with my pink Samsonite suitcases, waiting to move in uninvited. Unlike Jorge, Steve was happy to see me. Very happy, in fact. It had been almost a year since the last time we were together, an intense bout of sex in his dorm bed followed immediately by an epic fight when I found a pair of panties, not mine, in the sheets.

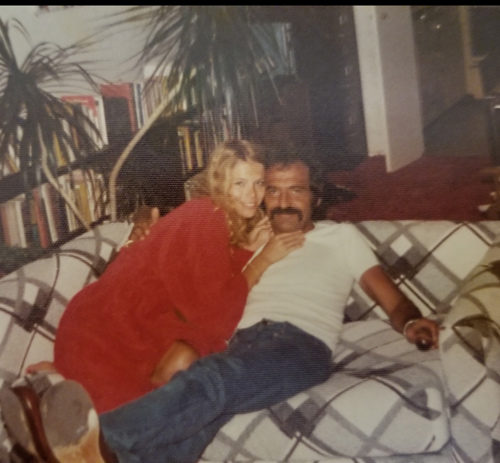

Now I was very thin (thanks to James), very tan, and very blonde. I tried to radiate a new sophistication, hoping that my recent Mexican adventures had made me more exotic and desirable than the nerdy brunette from Duluth Steve had met our freshman year. That girl was dead.

Steve looked exactly the same, small-town boy gone to the dark side, his smile still more of a sneer, costumed as the Caucasian Super Fly in a cheap white polyester suit. I couldn’t help but think that in that outfit, he would have been left standing in line all night outside Armando’s. But when we touched, that familiar and thrilling bolt of desire shot through me, making me catch my breath and hold him tighter. The two of us hustled up the stairs and into his new place.

It had taken years, but Steve had finally convinced Outward Bound to let move him out of the dorm and into an apartment of his own, an apartment they still paid the rent on. His new place was the top floor of recently built duplex not far from the university campus. A sign in front announced “Buttercup Complex Now Renting” or some such nonsense, but Steve’s building was the only one on the block: vacant lots surrounded the duplex on all sides, portioned out with stakes and string. The closest building was behind the duplex and across a field, a single story red brick creamery topped with a huge billboard featuring the Land O’Lakes Indian maid with her butter, her mysterious smile, and her plump knees sticking out of her buckskin garb.

Steve was upholding part of his deal with Outward Bound, puttering away nicely towards his degree in Accounting or Business or Pharmaceutical Sales. But he kept his eye on the prize and wanted to expand his drug dealing beyond his fellow dorm residents. He knew the quickest way to get busted and lose his scholarship would be to start buzzing in shady characters to his dorm room at all hours; drug dealing is the business that never sleeps. If he had his own apartment, he could expand his customer base and make even more money. Every few days he would drop into the dorm “to visit friends,” friends who in an emergency could come to him. He probably had a complete business plan, repurposed from some economics assignment, in place.

I can’t imagine that Steve’s benefactor from Outward Bound ever came to check up on him in his new digs, as there was always a wide sampling of drugs strewn across the coffee table, like a display case at a jewelry store. Most of his stash was tucked away in the freezer, while the cash was cleverly concealed in a Folgers coffee can on top of the bedroom TV. A steady stream of customers came by all day and pretty far into the night, as late as possible in a town where the bars shut at one. Sometimes they called first, sometimes they just showed up and banged on the door.

My original plan, concocted on the flight to Minneapolis, had been to hole up in Steve’s dorm for a few days till I found a place to live; but Steve welcomed me to stay as long as I liked in his apartment and his full-size bed, and I was happy to be there, happy to sit on his tiny back patio, smoking his pot with no one around except the Land O’Lakes maiden.

I did sneak in a quick phone call to James in Chicago. We talked about the weather and if I had signed up for summer classes yet. When conversation faltered I gave him Steve’s number to reach me without mentioning Steve himself.

I also phoned my mother to let her know I was alive. The only way to make a long-distance phone call in Acapulco was to go to the phone company, which was a shabby, un-air-conditioned edifice in the hot, steamy downtown. I did try to call my mom; I filled out the blurry form at the desk, and then stood in a long line waiting to enter a wooden phone booth, where I waited some more for the right number to be connected, which generally took two or three tries. I stood in that hot box, sweating and hoping someone would be at home to answer the damn phone. After my second fruitless attempt to reach my mother, the long-suffering look on James’ face as he sat smoking in the jeep discouraged me from trying again.

When I phoned her from Steve’s place, my mother was not as concerned about my going missing for six weeks as I thought she should be. She had a bigger problem. My sister Lani had appealed to have her custody switched to my father, and the minute that happened, dad gave Lani permission to marry her Colorado Springs boyfriend. The boyfriend was twenty-one, Lani was sixteen and about to be a June bride. Neither mom nor I were invited to the wedding. For some reason the fact that Lani had picked out a big virginal white wedding gown to get married in was what drove my mom over the edge. I knew she wasn’t listening to me, but I assured my mother I was fine, and hung up to the sound of her tearing out her hair.

As I had hoped, Pracna was happy to hire me back. They had opened the outdoor cocktail area overlooking the Mississippi River. People showed up at eleven in the morning to snag one of those tables, and every table outside and in was occupied till we closed the joint at one. I sweet-talked Steve into driving me to and from work, promising to introduce him to potential new customers, the hard-partying Pracna staff. I treated myself to a new pair of work shoes, lovingly tucked my growing bankroll into the empty shoebox, and slid the box way under Steve’s bed, till it rested back against the wall.

The deadline for enrolling in summer classes came and went. I was not ready to get back on the treadmill. I had always been an industrious ant; now I discovered that grasshoppers and blondes do have more fun. It was too pleasant waking up next to Steve, who was already rolling that morning’s first joint, and not having to go anywhere for hours. We were getting along better than we ever had before. Steve seemed mesmerized by the new me, and his outlaw life excited me enough to overlook his pimp-style wardrobe. Steve had grown up poor, his few articles of clothing were hand-me downs or from Goodwill, and children are cruel. He made up for that childhood deprivation now, with a closet full of candy colored wide brimmed hats, bell bottoms in every fabric except denim, shiny patterned shirts, and platform shoes of a tottering height that I would have plunged from, but that he managed to strut around in with aplomb.

Our only disagreements came from the fact that Steve did not want to leave the apartment. For a guy whose entire life was bankrolled by an outdoors education organization, Steve was reluctant to go outside. There were no cell phones, no beepers, not even answering machines, and he did not want to miss a single prospective buyer. But it was glorious summer in Minnesota, when the air is a balmy blessing and the grass a soft carpet. I was drifting along, with no thought for the future, but well aware that there were only a handful of summer days to enjoy. I wanted to be outside, coaxing what warmth there was to be had from the Minnesota sun on my still tan skin.

I would pout and fuss until I got Steve to drive us and a blanket and a bottle of something to Lake Calhoun (now Lake Bde Maka Ska) where we would snog publicly and smoke pot and drink surreptitiously, although in those days no one cared as long as we didn’t make a mess or too much noise. Sometimes I would get him out of his platform shoes and into a his old pair of hiking boots and we’d walk the trail to Minnehaha Falls, a bit of wilderness in Minneapolis that we often had all to ourselves. I even talked Steve into driving to the Corn on the Curb Festival, held in Le Sueur, home of the Jolly Green Giant, on the exact day when the corn stalks were as high as an elephant’s eye and the emerald fields waved gently under a summer sky bleached almost white. Steve claimed to hate small Minnesotan towns. But he took me anyway, after swallowing a few pills, and as his reward he got to see me eat twenty ears of corn while he pounded bottle after bottle of Schell beer and sneered at the yokels.

North Country Girl: Chapter 34 — The University of Drugs and Boys

Editor’s note: After much pleading by the Post, Gay Haubner has graciously agreed to continue her weekly series into her college years.

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

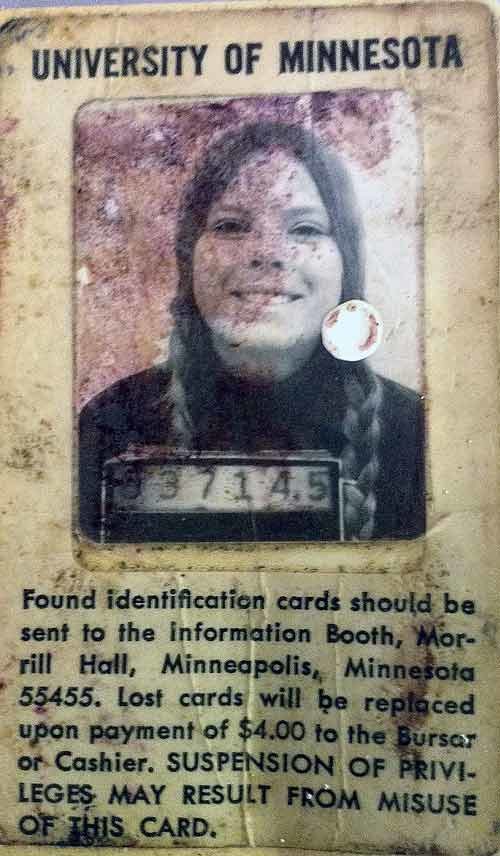

In the fall of 1971, I arrived at the University of Minnesota in the big city of Minneapolis, having finally emerged from the cocoon of the corn-fed Midwest middle-class. My parents deposited me into my fancy dorm (a bathroom that was shared with just three other girls! A comfy TV lounge on every floor! A soft serve dispenser in the cafeteria!), at the coed Middlebrook Hall. I had shed my high school boyfriend and had adopted a new persona, intellectual hippie chick. I was ready to put on my headband and purple fringed leather jacket and dive into this new world of college, a place filled with my favorite things: books, boys, and drugs.

I reveled in this Brave New World: curling up and trying to look adorable on a boy’s narrow dorm bed, buying sugar cube acid, five dollars a hit, from a pharmacy major, crossing the resplendently treed Minneapolis campus in still balmy September, heading to a fascinating class on Human Geography (“Today we’ll look at the consequences of the Irish Potato Famine.”)

I loved living in a place dedicated to learning, no matter how obscure the subject (I was also taking “Poets of the Russian Revolution”) and to rampant drug use, random sexual partners, and parties that featured garbage pails filled with a deadly mixture of Welch’s Grape Drink and Everclear, an overproof liquor with zero redeeming qualities. If the scales of my college life began to tip too far on the fun side, I had before me the cautionary example of Jean the Machine, who I shared a bathroom with, and who, after passing out face down in her dorm room, had to be ambulanced to the University Medical Center for alcohol poisoning, and who dropped out after two weeks without attending a single class.

My dad, who had exited from my life after his quickie second wedding and the birth of his son the following day, had been ordered by Judge Erman in the divorce settlement to pony up for my college tuition and dorm. Everything else—drugs, tampax, long underwear, emergency baked rigatoni dinners at Mama Rosa’s when I just couldn’t face another night of cafeteria cuisine—came out of my savings from my summer waitressing job. Since I had worked at a roadside café that catered to cheap ass tourists who figured they’d never be back so why tip more than a quarter, my stash of spending money vanished into pot smoke and red sauce.

By November I was standing behind the counter at my dorm cafeteria, wearing an ill-fitting yellowy-beige uniform with a dingy white collar and cuffs and a hair net. I had become a lunch lady, doling out helpings of pale haddock squares, runny lasagna, and grey Salisbury steaks that, three months into the school year, all of us Middlebrook residents were thoroughly sick of. I was paid $2.00 an hour but I had access to all the soft-serve ice cream I could eat between shifts, which turned out to be quite a lot.

I didn’t care. I was out of stuffy and stifling small town Duluth, and in a place where the boys were smart and funny and the wild weekend parties welcomed cute girls with open bottles. Since I cannot live without girlfriends, the universe gave me some new ones: my roommate Nancy and our remaining bathroom-mate, Liz, who after the departure of Jean the Machine, luxuriated in a dorm room all to herself. And every day I sat spellbound in my classes, enthralled by my brilliant professors. All the knowledge and culture and history of Western Civ was laid out for me like a smorgasbord. When I wasn’t in class or working in the dorm cafeteria, I was reading or taking drugs or meeting new guys. I was in heaven.

After a few weeks of flirting with every freshman, I landed a boyfriend of sorts. I have a talent for sniffing out the dangerous boys. When I inhale that mix of cigarette smoke, bit of unwashed skin, fairly recent sexual encounter, and a pheromone that tells me this boy would first fight and then take flight one step ahead of the law, that smell that lurks in a bad boy’s neck where it dips into his shoulder, I am head over heels in trouble.

My unfailingly stupid nose led me to the one juvenile delinquent in Middlebrook dorm, which was otherwise filled with the white-toothed, clear-skinned, shiny-haired sons of doctors and lawyers and Babbits of Minnesota. Steve Jones (could there be a more anodyne name?) was the first person I had ever met who affected an urban black swagger and patois lifted straight from Shaft, behavior as mystifying to me as it must have been to the residents of his hometown of Austin, famous mostly for acres and acres of Hormel Meats stockyards and slaughterhouses. The boys on his floor gave Steve the mocking nickname Jive Time. Steve took this as a compliment and adopted it himself, shortening it to JT.

In looks Steve was as unremarkable as his name: dirty blonde hair not quite long enough to be cool; a snub nose and a mouth that curved naturally into a sneer; medium height but with a taut, strongly muscled body that seemed ready to throw a punch.

Steve found me late one night while I was hanging out in the lounge on the freshman boys’ floor, kibitzing around a table of bridge players; a bunch of us had caught the bridge bug, so twenty-four hours a day there was a foursome shuffling and dealing cards, fueled on coffee or Coca-Cola. The other boys ignored Steve, as he jive walked up to me and leaned in so our arms touched. Every little hair on my body stood on end and gravitated toward him.

Steve said, “If you sissies played a real card game like poker, I’d beat all your asses.”

“Get lost, Jive Time,” chorused the bridge players, as if they had practiced this line for weeks. Steve cocked his eyes at me and I followed, a lamb to the slaughter, down the hall to his dorm room. His roommate looked at us as if we were slime, shook his head, and left. Steve kissed me and the top of my head went shooting off and my clothes dropped to the floor.

Steve had dabbled in a variety of crimes: joy riding, shoplifting, breaking and entering, arson, and drug dealing, which is what finally caused him to be hauled into Austin’s juvie court, next stop the infamous Red Wing Reform School for Boys. (When I was a teenager, Red Wing seemed a mythic place of punishment, like Hades or Limbo. The few boys I knew who got into serious trouble were shipped off to the Judson Ranch, a boarding school in the Arizona desert a million miles from nowhere.)

Steve was miraculously rescued from what would surely have been a life of petty, ill-fated criminality. The judge gave him a choice: he could do three months at Red Wing or spend the summer learning outdoor survival skills with Outward Bound’s program for wayward youth. The judge was swayed by the argument that if you can teach a boy to find his way out of the woods with three matches and a compass, that boy can learn to find his way in the world. Steve, who fancied himself more of an urban survivor, was ready to take on anything that wasn’t the boys’ reformatory.

Steve surprised himself by flourishing in Outward Bound. He learned rock climbing, rappelling, navigating by the stars, and how to catch, skin, and cook a squirrel. His instructors loved him, the juvenile delinquent they had transformed into Daniel Boone. Steve was the success story, trotted out by the head of Outward Bound at every speech, pitch, and fundraiser, the proof that learning to kill your own food can redeem a boy headed in the wrong direction, teaching him responsibility, self-reliance, and not to sell drugs or steal. Steve went along with the Outward Bound poster boy act; he knew which side his squirrel was buttered on.

Outward Bound made Steve an offer. Spend his summers as a counselor, teaching other kids to make lean-tos and start a fire from two sticks and, if he could keep his grades up and his nose clean, he would get a full ride to college, including a room in the fancy new dorm, that luckily for me, was just a few floors above mine.

Steve did not make friends with the privileged children of surgeons and bankers; even his roommate didn’t like him. He was all rough edges. Surviving in the woods did not teach him social graces or skills. He did, however, despite his promise to Outward Bound, supply our entire dorm with drugs. He was looking for customers, not friends.

One night, the two of us speedy and restless on Black Beauties, we drove to Steve’s hometown of Austin. It was after midnight when we pulled up in front of a ramshackle shotgun shack, that in my unpleasant altered state I barely recognized as a house. The entire structure could have fit into my family’s kitchen and dining room.

Steve’s mom was still awake, wearing what my subconscious identified as a “housecoat,” smoking Kools and drinking Schell’s beer in front of a flickering TV that sat upon a larger, dark TV. The floor was littered with empty beer cans. Steve kissed his mom, who ignored me as she launched into a slurred speech on the shortcomings of Jim, whom I assumed was her boyfriend. Steve watched the TV and nodded while I looked for a place to sit down where I wouldn’t have to move anything. Mom finally passed out while lighting a cigarette, and Steve gently transferred the cigarette from her lips to his, then led me into his old bedroom. We lay down, still ripped on the uppers, gritting our teeth, miserably awake and uncomfortable on that rack of a bed, which consisted of a bare, torn up blue ticking mattress, no sheet, no pillows, set on a metal frame. We both lay flat on our backs, staring at the ceiling, too amped to even blink. Every time we moved, the bed squeaked and the springs found new places to poke us. One spring must have hit a weird nerve in Steve.

“You know that money I get from Outward Bound?”

“Yeah.”

“There’s another reason they give it to me. The guy in charge, the chairman, he wanted me to do some things…he said if I did, Outward Bound would pay for college.”

It was like being back in the claustrophobic dark confessional at Holy Rosary Cathedral, except I was the confessor. A real Catholic priest would have demanded all the sordid details: as Steve rambled on more and more incoherently I couldn’t tell whether he had turned the guy down, actually done something sexual with him, or was still doing it. Waves of hot shame radiated off of Steve, pushing me into an ever more uncomfortable place. I hated this guilt-ridden version of my bad boyfriend, I hated the amphetamine buzz, the tortuous squeaky bed, the squalid house in the stinky town. Steve suddenly sat up, swallowed another Black Beauty dry, and said “Let’s go.” We drove back to Minneapolis in the silent dawn and never spoke of Steve’s mysterious pact with Outward Bound again.

Black Beauties and other amphetamines were among Steve’s top sellers, especially during the weeks before midterms and final exams. Any kind of pill was popular at Middlebrook. We were constantly threatened that if we were caught using drugs we would be kicked out of the dorm, and probably out of college as well. But the only drug you could really be caught with was pot, with its pervasive, lingering aroma no cone of incense could mask. There were Resident Advisers on every floor, seniors who lived in the corner single dorm rooms rent-free, whose main responsibility was to be on the look-out, or smell-out, for marijuana. It didn’t take us druggies long to realize if you’re caught smoking pot, you’re screwed. But you could ingest a wide variety of interesting drugs right under the noses of the RAs with no problem, as long as you didn’t strip off your clothes and run around naked or toss yourself out of an upper story window.

The one exception to the no pot rule was Middlebrook’s dorm rooms for handicapped students, the only ones on campus. These rooms were in a wing on the ground floor; if someone forgot to put a towel under the door, marijuana smoke would stream into the dorm’s lobby, causing raised eyebrows but never any repercussions from whoever was in charge. I guess nobody wanted to bust the handicapped kids for smoking pot.

Steve’s best customer was a wheelchair-bound student who lived in one of those ground floor dorm rooms. Number One Customer was mostly torso and had an oversized head with a six-inch high forehead topped with stringy white blonde hair, which he wore to his shoulders. His arms were stunted, like tyrannosaurus rex arms, and his legs were small, shriveled appendages.

My cotton wool upbringing meant that I had rarely been exposed to death, poverty, or seriously damaged bodies. Once, at the Norshsor theatre watching 101 Dalmatians, a girl sat down next to me and propped her arm, which ended at the elbow, on the rest between us. I had no idea anything that awful could happen to a kid my age and spent the entire movie trying not to stare at her stump while leaning as far away from it as possible. The same scary, sick feeling sat like a stone in my stomach every minute I spent in that smoky, weirdly equipped dorm room. I was emotionally stunted, unable to dredge up a twinge of empathy or sympathy.

Number One Customer had two things I had never seen before: a bong and an electric wheelchair. He was supposed to be brilliant, a proto-Stephen Hawking. He also had a huge pot and psychedelics habit. At least once a week Steve and I would be sitting on his couch, Steve in full salesman mode, pitching whatever he had that day, while I tried to look at anything other than the guy in the motorized wheelchair cradling a two-foot bong between his tiny palms. Number One Customer gobbled LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin, in alarming doses and was always trying to get us to trip with him. But Steve didn’t like psychedelics and I was completely freaked out by the whole scene; for me it was already a bad trip. Making it even weirder was the fact that Number One Customer had a full-time student aide, Kit, who lived with him and who I had slept with during freshman orientation week. Kit did not partake in this feast of drugs: he just smiled at me through the clouds of pot smoke, as I outwardly beamed and looked friendly and inwardly squirmed, sending out a desperate telepathic message: “Let’s go, Steve let’s go, Steve, let’s go…”

Illegal substances popped, snorted, and smoked, fueled my romance with Steve, a romance that was fiery, melodramatic, and slightly stupid, but as addictive as a bad drug. Steve and I would cheat on each other as if it were an Olympic competition, and since neither of us bothered to hide our tracks, these infidelities spurred raging, nasty fights. Sexual jealousy ran hot in our veins, made pits in our guts. It stopped short of violence; we used words to batter each other.

“You’re a stuck up bitch. Go on back to those card-playing chumps. Get your s**t and your ass out of my room.”

“And you go ahead and screw any other girl who’ll have you, we’re done. You think you’re all cool and black but you’re just an ignorant, dirty greaser.” On the tip of my tongue was “You wouldn’t even be in college if some old man hadn’t wanted to…” but I always bit it back.

We would break up for weeks, looking away when we ran into each other in the dorm cafeteria or lobby. I made regular trips to the floor Steve lived on, for bridge or TV or just to hang out, to make sure that Steve would see me flirting or kissing or vanishing into a dorm room with other guys.

Making up was inevitable; our hormones demanded it, and it was as intense and exhausting as our fights. We would declare a truce, tumble into bed, and then spend every day and night together, transforming his dorm room into a fuggy, musky nest, interrupted occasionally when his disgruntled, disgusted roommate knocked to retrieve his clothes or books. I only left Steve’s bed to serve cafeteria haddock or to go to class. And then we would break up again.