Tricking Beethoven into Performing

In the March 25, 1826, issue, the Post printed a traveler’s account of a visit to Beethoven in Germany.

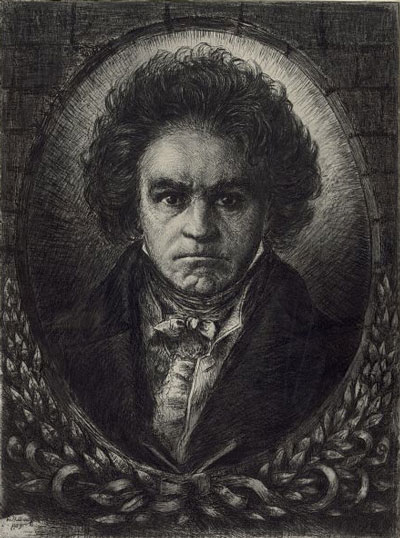

By this time, the 55-year-old composer was completely deaf and suffering from physical ailments that left him irritable, impatient, and moody. He had revolutionized the symphony, and was taking chamber music to new heights of expressiveness. And he was famous enough for American readers of the Post to have heard of him.

But Beethoven had also built a reputation for eccentricity. The author describes him as filthy, with “bearish” manners, yet capable of a brilliant, impromptu performance on the piano.

Today, many performers adopt a personality that’s based on the romantic notion of the musician is someone possessed by genius and living by his or her own rules. Whether or not they know it, the temperamental rock star, imperious diva, and bad-boy vocalist all owe their public character to the man who unwittingly created it: Beethoven.

Beethoven

Originally published on March 25, 1826

He is very deaf, and therefore has always a small paper book with him and what conversation takes place is carried on in writing. In this, too, he instantly puts down any musical idea which strikes him. These notes would be utterly unintelligible even to another musician, for they have thus no comparative value, he alone has in his mind the thread, by which he brings out this labyrinth of dots and circles the richest and most astonishing harmonies.

The moment he is seated at his piano, he is evidently unconscious that there is anything in existence but himself and his instrument and considering how very deaf he is, it seems impossible that he should hear all he plays. Accordingly, when playing very piano, he often does not bring out a single note. He hears it himself in the “mind’s ear;” while the eye, and the almost imperceptible motion of his fingers, show that he is following out the strain in his own soul, through all its flying gradations, though the instrument is actually as dumb as the musician is deaf.

I have heard him play; but to bring him so far required some management, so great was his horror of being anything like exhibited. Had he been plainly asked to do the company that favor, he would have flatly refused. He had to be cheated into it; every person left the room except Beethoven and the master of the house, one of his most intimate acquaintance. These two carried on a conversation in their paper book about bank stock. The gentleman, as if by chance struck the keys of the open piano, beside which they were sitting; gradually began to run over one of Beethoven’s own compositions, made a thousand errors, and speedily blundered one passage so thoroughly that the composer condescended to stretch out his hand and put him right.

It was enough: the hand was on the piano; his companion left him on some pretext, and joined the rest of the company, who, in the next room, from which they could see and hear every thing, were patiently waiting the issue of this tiresome conjuration.

Beethoven, left alone, seated himself at the piano. At first he only struck now and then a few hurried and interrupted notes, as if afraid of being detected in a crime; but gradually he forgot every thing else, and ran on during half an hour, in a phantasy [sic], in a style extremely varied, and marked above all by the most abrupt transition. The amateurs were enraptured; to the uninitiated it was more interesting to observe how the music of the man’s soul passed over his countenance.

He seems to feel the bold, the commanding, and the impetuous, more than what is soothing and gentle. The muscles of the face swell, and its veins start out; the wild eye rolls doubly wild; the mouth quivers: and Beethoven looks like a wizard overpowered by the demon whom he himself has called up.