The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

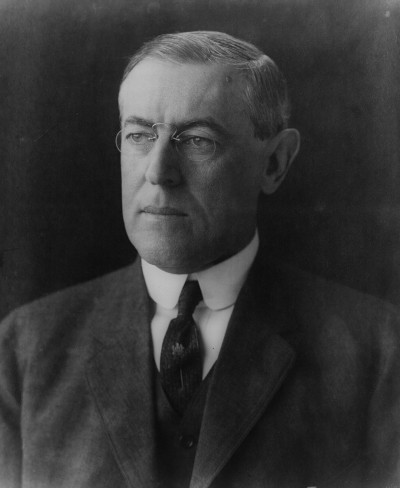

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

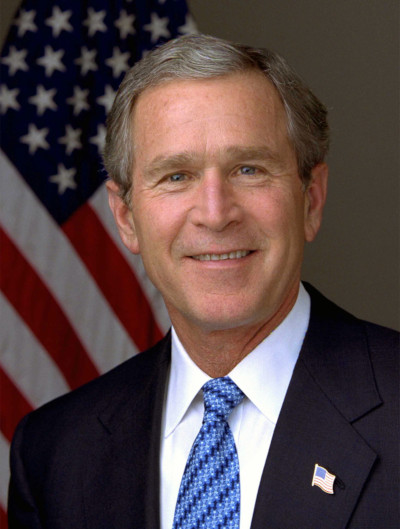

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

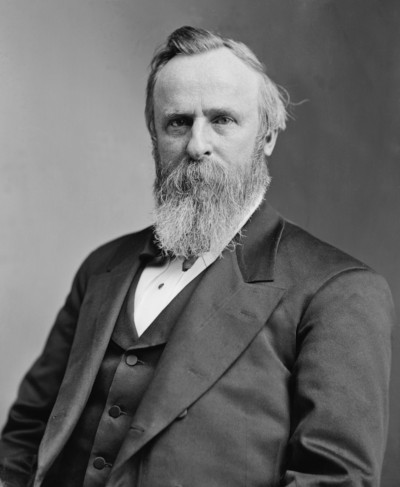

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

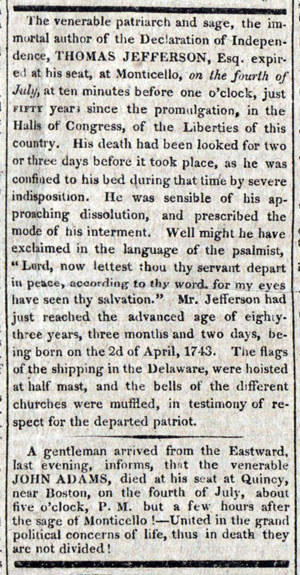

The Debt and Death of Thomas Jefferson

The news in the July 8, 1826, issue of the Post must have seemed incredible: “the immortal author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, Esq. expired at his seat, at Monticello, on the fourth of July, at 10 minutes before 1 o’clock.”

It scarcely seemed possible that 83-year-old Jefferson had lived just long enough to reach the 50th anniversary of America’s independence.

While readers were taking in this news, they would have been astounded to read in the next column: “A gentleman arrived from the Eastward, last evening, informs us that the venerable John Adams died at his seat at Quincy, near Boston, on the fourth of July, about 5 o’clock p.m., but a few hours after the sage of Monticello! United in the grand political concerns of life, thus in death they are not divided!”

The report continued, “On the morning of the Jubilee, he awoke at the ringing of the bells and the firing of cannon; the servant who watched with him said, ‘Do you know, Sir, what day it is?’

“‘O yes!’ he replied, ‘it is the glorious 4th of July — God bless you all.’”

Just an hour before his death, visitors asked him for a toast, which they could give that evening. He said, “I will give you ‘Independence forever.’”

A woman present asked him if he wished to add anything.

He answered, “Not a syllable.”

At his death, John Adams was able to bequeath land and books to start a school in his town of Quincy, Massachusetts. Years before, he had faced financial ruin when his London bank collapsed. Fortunately, his son, John Quincy Adams, came to his rescue by selling one of his houses and cashing in several investments. By his action, he left his father free of debt and still in possession of 275 acres of land.

(Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Down in Monticello, the end for Thomas Jefferson wasn’t as serene. Readers of the Post knew that Jefferson had spent his final months trying to free his estate from debt before he died. According to Thomas Jefferson Randolph, his grandson, the former president’s debts exceeded $100,000.

Jefferson had struggled with debt most of his life. To some degree, he was responsible for his financial troubles. He loved good living and he’d spent a fortune building and furnishing his mansion, Monticello. And, as he admitted to grandson Randolph, he hadn’t been skillful manager of his estate.

But he’d also been hurt by “the unfortunate fluctuations in the value of our money, and the continued depression of farming business.” Jefferson’s income was closely tied to those of his neighbors, since he was a creditor was well as debtor. When a poor growing season kept neighboring planters from repaying their loans to him, Jefferson would sink deeper into debt.

Some of his debtors had repaid his loan in Continental currency, but once America had become independent, the British merchants to whom Jefferson owed money would no longer accept these dollars in payment.

Jefferson had also been saddled with a sizeable debt inherited from his father-in-law. And in 1817, a friend asked Jefferson to endorse notes to repay a $20,000 debt. The friend died without clearing the debt, and that amount fell to Jefferson.

Many of the Founding Fathers had similar money troubles; George Washington and James Monroe died in debt. So did Alexander Hamilton, who was so poor that mourners at his funeral had to pass around a hat to gather the cash needed to bury him.

The social leaders of the new country might have been land-rich — Washington, for example, owned over 35,000 acres — but with few cash buyers of land, they had trouble applying their wealth to their debt.

Jefferson realized that, unless he cleared his debts, his daughter would have to follow his path, continually fighting for financial independence. Creditors had refrained from hounding Jefferson for repayment, out of respect for one of the nation’s architects. But they might not be as considerate to his daughter.

Desperate to raise money, Jefferson hit upon a unique solution. He and his grandson, Randolph, would run a lottery. The winner would gain title to Jefferson’s lands, including his beloved Monticello, which he had built over the course of 56 years. It was appraised at $71,000 ($1.5 million today.)

In April, the Post reported, “Messrs. Yates and McIntyre [of New York city] have the management of Mr. Jefferson’s lottery. There are 11480 chances at $10 each. The books for subscription were opened at Washington on Saturday, and it is said the tickets will be ready for delivery in a very short time.”

Jefferson was pleased to learn the country’s initial response to his scheme was generally positive. Yates and McIntyre had even agreed to run the lottery without charging a fee. Furthermore, the Post reported, “Lottery brokers are to sell the tickets without profit.” One Baltimore citizen had begun urging his fellow citizens to buy tickets and then burn them on July 4th , enabling Jefferson to pay off his debts and keep his property.

But then, several prominent citizens in New York proposed that Jefferson abandon the lottery. They said they would launch a fundraising campaign that would pay his debts without his losing his lands. Jefferson agreed.

But the campaign raised only $16,500 before it was ended. Jefferson asked that the lottery be revived. But now the initial enthusiasm had faded. Ticket sales were disappointing.

Fortunately, Jefferson died without knowing that his scheme wouldn’t work. He had only heard news of broad support from across the nation. He could now look back on his life with contentment. In a letter to his grandson, reproduced in the Post, he wrote that he had no reason to complain about his money worries, “as these misfortunes have been held back for my last days, when few remain to me. I duly acknowledge that I have gone through a long life, with fewer circumstances of affliction than are the lot of most men. Uninterrupted health, [sufficient money] for every reasonable want, usefulness to my fellow-citizens, a good portion of their esteem, no complaint against the world, which has sufficiently honored me, and, above all, a family which has blessed me by their reflection, and never by their conduct given me a moment’s pain. And, should this my last request be granted, I may yet close, with a cloudless sun, a long and serene day of life.”

After his death, lottery ticket sales fell sharply; Americans weren’t as enthusiastic to help Jefferson’s heir. And now several states were raising objections to the scheme. By 1828, Randolph conceded the project had failed.

Jefferson’s estate, and debt, were inherited by his daughter, Martha Washington Jefferson Randolph. She soon began selling off the estate. She was forced to sell Monticello in 1831. She also sold the 130 slaves still held on the estate.