Travel Abroad without a Passport: Miami

MIAMI — I hear the staccato rap of the congas several blocks before I spy the salsa trio and the dancer, dressed in a canary yellow cha-cha-cha costume, who sways back and forth in the doorway. It’s not quite noon, yet brunch is teeming with revelers, several of whom have already imbibed in a twirl with the animated maraca player. I’ve arrived at the Ball & Chain Bar and Lounge in the fabled Little Havana neighborhood. It’s one of America’s legendary clubs, host to Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and, just last night, the Tito Puente Jr. Band. (Full disclosure: I didn’t leave the show until just after 2 a.m.!)

I initially encountered Miami’s cultural mélange a couple of years ago when transferring at Miami International Airport. Walking between gates, I couldn’t help but notice the diversity, coupled with the lively conversation of seemingly everyone who disembarked toward baggage claim. I resolved at that moment to follow this intriguing aggregation of Spanish dialects, Haitian Creole, and other languages onto the Miami streets at a later date. Am I glad I am doing so now!

I spend my first morning in Coconut Grove, a fitting launch point. This historically Bahamian enclave was home to the workers who labored in early Miami fields, built its homes, and provided the critical population mass for the city to incorporate on July 26, 1896. It’s considered the oldest neighborhood in Miami. “Only 300 Americans were living here at the time, and the founders needed twice that number to incorporate,” explains Cultural Heritage Alliance for Tourism (CHAT) guide Keith Ivory, a third-generation Miamian descended from Georgia sharecroppers who resettled here.

We’re strolling beside the Charlotte Jane Memorial Park Cemetery, named for the wife of E.W.F. Stirrup, a Coconut Grove Bahamian immigrant who became one of America’s first Black millionaires. The cemetery’s partially raised crypts are hardly its only distinction — the densely wooded graveyard inspired Michael Jackson’s Thriller video, the most popular music video of all time. Long a cultural and creative enclave, Grove residents have included Tennessee Williams and Robert Frost as well as, more recently, LeBron James and Madonna. The arts remain at the forefront of the district’s current renaissance. The Coconut Grove Arts Festival draws more than 350 artists every February, and each June the Goombay Festival celebrates Bahamian culture.

“This area has always been culturally important,” Ivory explains. “Black performers would play at the white-only clubs, then return to The Grove and stay at the Peacock Inn. Pretty much any Black musician you’ve heard of stayed here at some point.”

Miami’s settlements, Coconut Grove, Little Haiti, and Little Havana in particular, are known well beyond Dade County. Their history represents the promise of America, and their influence stretches across the city, transcending language — Spanish is almost universally spoken here — and ancestry to fashion a marvelous multi-ethnic mural of civility and pride.

The swagger infuses the most familiar of places in the booming metropolis as well. Once an eyesore of failed businesses, Miami’s Bayside Marketplace now bustles with restaurants, boutiques, and an amphitheater hosting live music most weekend nights. This natural performance space, set among boat tour kiosks and souvenir shops, is packed with visitors swaying and dancing to a samba band, the mood as bright as the red lights illuminating the adjacent Freedom Tower, named for its role as processing facility for refugees fleeing the Cuban Revolution.

In the evening I board the Island Queen for the “Full Moon Over Miami River Cruise” with Dr. Paul George, a retired history professor and leading expert on South Florida history. George leads a range of neighborhood walking and boat-based tours throughout the year in association with HistoryMiami Museum, where he is the resident historian. His enthusiasm and knowledge seem inexhaustible — even extending to each of the eight drawbridges we pass under over the course of two hours.

“The Twelfth Avenue Bridge was built with pedestrians in mind as well as cars,” George announces. “Look back as we pass under and you will see the stairs — see there they are — that were really unusual at the time. They gave people access to the riverfront!”

He goes on to explain how the riverfront actually reflects Miami’s economic health even more so than the port, which is among the busiest in the world. “Look at how the sun is setting so beautifully on the Brickell Bridge!” he exclaims. “The sun is definitely not setting on Miami at the moment; every square foot of available property along this river has been purchased by developers. This whole restaurant row was a marine supply warehouse just a couple of years ago.”

Miami’s Bayside Marketplace is packed with visitors swaying and dancing to a samba band, the mood as bright as the red lights illuminating the adjacent Freedom Tower.

As if on cue, a large party yacht passes us en route to mooring outside Garcia’s Seafood Grill and Fish Market, a stalwart dining room from the rusting river yard days that continues to serve what many locals consider the freshest catch in the city. The city lights glisten magically on the gentle current as each bascule bridge broadens like an alligator’s jaw to invite passage toward Biscayne Bay.

Miami cuisine also unfurls as gloriously in this city, a culinary mecca for many of the brightest chefs in the Americas. The cacerolazo, the “banging of pots,” occurs here, not in traditional protest but in celebration of a future where South American spice is blended with the freedom to experiment in the kitchen.

I’m sitting in the atrium at CVI.CHE 105, Lima-born Juan Chipoco’s award-winning downtown seafood restaurant. Señor Chipoco is largely responsible for educating Miamians, and in fact all food-loving Americans, about Peruvian cuisine, specifically ceviche, raw mixed seafood marinated in subtropical flavors such as Chulucanas’ lime juice, Arequipan onions, cilantro, and hot sauces. Like the sushi revolution before it, ceviche continues to change the way home cooks approach raw seafood.

“The Peruvians create the world’s greatest ceviche,” my bartender, a Dominican, tells me, “though don’t say that to an Ecuadorian. And never discuss steak in the presence of an Argentinian or a Brazilian. It won’t end well.”

I had planned to order Pescado a lo Macho (spicy fish wrapped with seafood in a signature cream sauce), but the mixed seafood ceviche more than satisfies my appetite. Sushi has been my desert island meal for decades, but ceviche — citrus-blended squid and shrimp so fresh they perform backflips upon my palate — is definitely gaining ground.

I’m back in the park first thing next morning, this time to walk along the water just beyond already buzzing Bayside Marketplace to Maurice A. Ferré Park (formerly Museum Park), home to the Frost Museum of Science, Pérez Art Museum Miami, and, several times a year, music festivals that draw upward of 50,000 people. The park was established for the American bicentennial but fell into neglect because people were not yet returning to live and play in the Miami city center or in any other urban hubs across the country. Fast forward four decades and the park is bustling with families visiting the science center, couples nestling into giant swinging steel chairs (a sculptural installation, Netscape by Konstantin Grcic) tethered along with hanging gardens from the Pérez Museum roof, and museum goers dining at Verde, the museum’s al fresco restaurant.

“The Peruvians create the world’s greatest ceviche,” my bartender, a Dominican, tells me, “though don’t say that to an Ecuadorian.”

Next, it’s off to Little Haiti, whose focal point is the Little Haiti Cultural Complex (LHCC). Just 15 years after breaking ground, the complex receives more than 100,000 visitors a year drawn to its galleries, Caribbean marketplace, performances, and classes. The LHCC campus includes an art gallery, dance studios, and a community center. The 300-seat Proscenium Theatre and an outdoor stage feature weekly performances from Afro-Caribbean dance troupes and musicians as well as open mic and poetry slam events.

“‘Sounds of Haiti’ brings the entire community out the third Friday of every month,” says Abraham Metellus, LHCC General Manager. He also notes the Complex becomes a major tourist destination during Art Basel, when the collection is guest curated by a Caribbean artist.

Without a doubt, Little Havana,” was Dr. George’s reply when I inquired after his favorite Miami neighborhood. After just a few steps into Calle Ocho, Southwest 8th Street, I see why, the district a sublime and rarely achieved blend of nostalgia and contemporary aesthetics, often within the same space. Here are the elegant and elderly gentlemen playing dominos in Maximo Gomez Park, a 35-year tradition rarely interrupted. (When Hurricane Irma temporarily closed the park in 2017, the players set up folding tables on the adjacent sidewalk to resume their customary play.) Here, too, are the famous cigar shops where novices or connoisseurs can enjoy hand-rolled perfection on premises.

Cuban coffee, arguably the world’s best, also permeates the air. And the scents emanating from Guayab y Chocolate draw me into Futurama, Little Havana’s artist collective that houses 12 artist studios as well as numerous monthly music and art events. Katey Penner’s jazz artists, Fredy Villamil’s cubist portraiture, and Joseph Woodward’s beguiling miniature paintings offer a sampling of artistic accomplishment within the circular studio space.

Later, at Old’s Havana Cuban Bar and Cocina, a bistro bursting with joy as vivid as the yellow walls that surround us, I watch in astonishment as the bartenders set up mojitos the way I might dream of planting tulip bulbs, my garden bloom paling in comparison to the 350-plus rum-based cocktails they prepare on an average weekend night. I claim one mojito while dining on lechón asado, traditional Cuban pork that has marinated for several hours, served with yuca fries and fish croquettes. Somehow two determined couples have found a dance space in the tiny area in front of strumming guitarists. I can easily imagine how the dance “floor,” as it were, often spills past the terrace tables onto the sidewalk.

There’s minimal barrier separating indoors and outside here in Little Havana. Call it the tidal effect, that unseen pull that draws you deeper into the froth.

I always seem to forget, and therefore appreciate more, how enticing the tropical al fresco lifestyle can be. As in Cuba and the rest of the Caribbean, there’s minimal barrier separating indoors and outside here in Little Havana. Call it the tidal effect, that unseen pull that draws you deeper into the froth, in this case an intoxicating culture.

Miami’s rhythm of mambo, cha-cha-cha, and other Caribbean music affects you for days after you experience it. You stand a little taller and add some strut to your step. Your surroundings appear more vivid, canary yellow, say, and yes, your smile stretches a little wider.

Miami itself, like its music, is a thriving cultural fusion that nourishes visitors, immersing them in a multicultural celebration and drawing them always to find the next dance … and the next … and the next.

Writer/photographer Crai S. Bower seeks wilderness and urban adventures wherever he goes, from stalking Komodo dragons in Indonesia to opera, oysters, and street art in Montréal. He lives and writes in Seattle. His exploration of Miami occurred before the outbreak of COVID-19. For more, visit flowingstreammedia.net.

This article is featured in the March/April 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Dancers in Miami’s “Little Haiti” Neighborhood (Courtesy Greater Miami Convention and Visitors Bureau)

The Best Road Trips in Every State

We scoured the nation for the best driving excursions in every state. Many showcase stunning fall foliage backdrops. Others present unique and spectacular geography. In some cases, we bypassed the best-known byways to feature hidden gems. Oh, we surely missed some — there are just too many to choose from. (Let us know your favorites in the comments below..) We hope to inspire you to venture out and explore this beautiful country we call America. Happy motoring!

Alabama

Wrapping around Mobile Bay on Alabama’s southern tip, the 130-mile Coastal Connection Scenic Byway runs alongside pristine, powder-white Gulf beaches, shorebird sanctuaries, pecan and produce farms, and historic Fort Gaines and Fort Morgan.

Alaska

Dream of driving from Fairbanks to the Arctic Circle? Then gas up and prepare to not see another human soul for hours, just lots of wildlife, including migrating caribou, Dall sheep, musk oxen, and arctic foxes. While spellbinding, the rugged 415-mile mountain-pass Dalton Highway is largely void of civilization and creature comforts.

Arizona

A favorite of motorcyclists and sports car enthusiasts, the harrowing 123-mile Coronado Trail, aka Devil’s Highway, ascends, narrows, dips, and twists through more than 400 switchbacks as it climbs from high desert floor to 9,000-foot alpine forest.

Arkansas

Arkansas’s 363-mile section of the multi-state Great River Road runs alongside the Mississippi River through its Delta region, brimming with ancient Native American and Civil War sites, steamboats, and Mark Twain’s boyhood haunts.

California

U.S. Route 395, “El Camino Sierra,” stretches from Mexico to Canada, and the California section packs in some of its most diverse landscapes: 14,000-foot peaks, tufa formations, ancient volcanos, ghost towns, and a bristlecone pine forest.

Also check out: The Gold Rush Highway journeys through California’s gold rush era in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas.

Colorado

Drivers cross the Continental Divide twice while traversing the Top of the Rockies Scenic Byway’s 82 miles from Aspen to Copper Mountain. The road seldom drops below 9,000 feet while passing through three national forests — Pike, Arapaho, and White River — abounding with bighorn sheep, red-tail fox, and mountain goats.

Connecticut

Rolling hills, covered bridges, historic taverns, charming villages … the vast array of Litchfield Hills Loop’s scenic routes will have you wondering if you’ve been dropped in an Andrew Wyeth canvas.

Also check out: Trailing the coastline, the 105-mile Connecticut Coast Scenic Highway between Stonington and Greenwich features salt marshes, wide beaches, and some of the East Coast’s oldest towns.

Delaware

Tranquil, two-lane Bayshore Byway parallels the Delaware Bay and migratory flyways between New Castle and Lewes. Antique-filled towns give way to corn and soybean farms, wildlife refuges, and marshlands.

Florida

The southernmost leg of Route 1 spans 165 miles over scenic bridges from Miami to Key West, showcasing coral islets, reedy wetlands, and unobstructed sunsets over the aquamarine sea. Watch for white herons, roseate spoonbills, pelicans, and dolphins.

Georgia

Three-state Russell Brasstown Scenic Byway travels 40 miles through Georgia’s mountain country, crisscrossing Brasstown Bald (Georgia’s highest peak), granite canyons, and the Chattahoochee River.

Hawaii

Just 11.2 miles long, the Big Island’s Mauna Loa Road traverses lava fields and koa forests while climbing majestic Mauna Loa for panoramic views of Kilauea volcano.

Also check out: Famed for its 620 curves and 59 bridges, Maui’s Hana Highway abounds with fragrant South Pacific foliage (think rainforests, cascading waterfalls, and multi-hued beaches).

Idaho

The Ponderosa Pine Scenic Byway’s 131 wooded miles wend from Boise to Sun Valley, past old gold mines, Western towns, and national forests, including the massive Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness.

Illinois

Nicknamed a “living museum,” 150-mile Illinois River Road Scenic Byway embodies more than 100 nature-based, historic, and cultural sights, including Lewistown’s Dickson Mounds Museum, which interprets the ecology of the Illinois River.

Indiana

The Indiana track of America’s first paved transcontinental route, the Lincoln Highway, includes a sundry of historic sites (some commemorating Abraham Lincoln) a circa-1889 synagogue, and lodgings from the early days of road-tripping.

Iowa

Travel the 82-mile Covered Bridges Scenic Byway across Madison County and see the five famous bridges. Also drive by the birthplace and museum of legendary actor John Wayne and the stunning Iowa Quilt Museum, both in Winterset.

Kansas

Western Vistas Historic Byway, a 102-mile, one-time pioneer and cowboy trail (trod by the likes of “Wild Bill” Hickok), encompasses extraordinary landscapes, 70-foot spire Niobrara Chalk formations, dinosaur fossils, and limestone-ledged buttes amid roaming buffalo and prairie dogs.

Kentucky

Trekked by Daniel Boone, Civil War soldiers, and European explorers, the 92-mile Wilderness Road Heritage Highway features Cumberland Gap National Park, mountain music venue Renfro Valley, and Kentucky’s crafts capital, Berea.

Louisiana

Bayou Teche Byway loops 125 miles through lush bayous, Acadian cultural districts, and the country’s largest wetland, the million-acre Atchafalaya Swamp Basin.

Maine

The 125-mile Bold Coast Scenic Byway winds through Downeast Maine’s craggy seashore, foggy coastal forests, blueberry barrens, and historic towns Milbridge and Eastport, filled with maritime heritage.

Also check out: Old Canada Road National Scenic Byway, a mountain-hugging trail tracing a logging-era U.S.–Quebec trade route.

Maryland

Three hundred years of history, marked in significant mileposts, tollhouses, taverns, and stone arch bridges, line the Historic National Road’s 170 miles spanning Baltimore to Maryland’s western border.

Massachusetts

Mohawk Scenic Byway began as a Native American trade route. Centuries later, Benedict Arnold marched his army here. Today, its 69 miles offer centuries-old churches, mountain passes, pristine rivers, and quaint towns.

Michigan

U.S. Route 23 stretches from Florida to northern Michigan. Avoid all of it … except its final 200 miles along Lake Huron’s Sunrise Coast. The panoramic Huron Shores Heritage Route snakes along hardwood forests, waterfalls, sand dunes, and freshwater beaches.

Minnesota

Road trippers pass by four of Eastern Minnesota’s state parks, basalt rock cliffs, steep gorges, and 19th-century towns, including lovely Stillwater, following the 124 rolling miles of the St. Croix Scenic Byway.

Also check out: Minnesota River Valley National Scenic Byway, 287 miles of prairies, woodlands, and Dakota heritage.

Mississippi

Traversing three states, the Natchez Trace was once an east-west passage for Native Americans, slave traders, and campaigning presidents. Mississippi’s 308 miles include a Plaquemine-culture ceremonial site, the antebellum Windsor Ruins, and Elvis’s birthplace.

Missouri

Just 27 miles long, Glade Top Trail in the Ozarks is the Show Me State’s only National Forest Scenic Byway. Largely unchanged since its construction by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, its many panoramic “pull-outs” showcase limestone glades, tall-grass prairies, and eastern red cedars in the Mark Twain National Forest.

Montana

The All-American Scenic Byway Beartooth Highway abuts a plethora of national forests, climbs high alpine plateaus, overlooks glacial lakes, and crosses the 45th parallel — the halfway point between the North Pole and Equator.

Also check out: Seeley-Swan Scenic Drive spans 90 miles between the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Mission Mountains.

Nebraska

Outlaw Trail Scenic Byway’s 231 miles of rough, rambling topography made it a prime hideout for Old West bandits like the James Gang and Doc Middleton. Sights include Smith Falls (Nebraska’s tallest), Monowi (a one-resident town), and authentic cowboy saloons.

Nevada

The landscape fluctuates between high and low desert microclimates along 355-mile Great Basin Highway. Don’t miss the Miller Point and Mathers Overlooks, Lehman Caves, and the 19th-century Ward Charcoal Ovens.

New Hampshire

The Kancamagus Scenic Byway’s 34.5 alpine miles through the White Mountains deliver monumental panoramic overlooks (especially the 2,860-foot Kancamagus Pass), dramatic bluffs, lush forests, and Sabbaday Falls.

New Jersey

Bucolic 89-mile CR-519 feels more New England than central Jersey. This country lane twists through picturesque woodlands with idyllic rivers, wholesome farmsteads, and tiny towns. Fittingly, it’s nicknamed The Land of Make Believe Highway, after one of its many roadside attractions.

New York

We’ll bet no other 30-mile drive ever felt as thrilling. Interconnected by a series of stunning mountain passes, the Adirondacks’ High Peaks Scenic Byway ascends through verdant forests and past crystal-clear waterways, offering views of more than 40 peaks that soar over 4,000 feet.

New Mexico

Trail of the Mountain Spirits Scenic Byway weaves for around 100 miles through high desert forests and wilderness regions where Wild West explorers once roamed. Interspersed within jaw-dropping vistas are the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, desert towns, and the Continental Divide.

North Carolina

Sandwiched between the Atlantic Ocean and Pamlico Sound, Outer Banks National Scenic Byway breezes through 138 miles of driving (plus another 25 miles by ferry) alongside salt-air beaches, sea turtles splashing around barrier islands, quiet coastal villages, and wildlife refuges.

Also check out: Famous Blue Ridge Parkway, America’s longest linear park, runs 469 miles through the breathtaking Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and Virginia.

North Dakota

Extending 64 miles from the Killdeer Mountains to the Badlands, Killdeer Mountain Four Bears Scenic Byway’s hilly landscape provides visual respite from North Dakota’s flat, barren terrain. The drive is a cultural tour of the region’s history, featuring the 1864 Killdeer Mountain Battlefield and the reservations of native Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes.

Ohio

The 26.4-mile Hocking Hills Scenic Byway offers so many Instagram-worthy vistas and must-see historic sites, driving it could take the whole day. The road winds around Hocking Hills State Park’s towering Black Hand sandstone cliffs, carved gorges, recessed caves, and plunging waterfalls.

Oklahoma

Nineteenth-century Texas ranchers drove millions of cattle across the Chisholm Trail to Kansas for beef distribution in the north. The Oklahoma portion (now US-81) is exquisitely rural, with sightsee stops dedicated to cowboy and outlaw history.

Oregon

The Pacific Coast Scenic Byway follows Oregon’s 363-mile coastline. Public beach access is protected by state law, ensuring opportunities for up-close views of soaring cliffs, marine caves, dunes, splashing sea lions, and naturally formed landmarks.

Also check out: Circling from Baker City to Le Grande, Hells Canyon Scenic Byway snakes above America’s deepest (7,993 feet) canyon.

Pennsylvania

The 265-mile Scranton-to-Warren portion of Scenic Route 6 is at its most impressive in the Endless Mountains, Pennsylvania Wilds (home to Pennsylvania’s Grand Canyon), and the hardwoods and hemlock of the Allegheny National Forest.

Rhode Island

Covering just 13 miles in the nation’s smallest state, RI-77 offers waterfront Sakonnet Peninsula vistas and alluring places to explore: Nonquit and Nannaquaket Ponds, the Emilie Ruecker Wildlife Refuge, and historic towns Tiverton Four Corners and Little Compton.

South Carolina

We love 118-mile Cherokee Foothills Scenic Highway’s picturesque path through the Blue Ridge Mountain’s Piedmont region, featuring glistening green forests with cascading waterfalls, jagged granite cliffs, and the postcard-perfect mountain town Walhalla.

South Dakota

The 68-mile Peter Norbeck National Scenic Byway drives like an amusement park ride, tackling hairpin curves, spiraling bridges, plunging tunnels, and granite pinnacles. Mt. Rushmore and Cathedral Spires are added bonuses.

Tennessee

The Cherohala Skyway gives you mile-high views of the Cherokee and Nantahala National Forests as it zigzags past freshwater mountain lakes and waterfalls, crimson and gold vistas, and apricot fall foliage.

Texas

The longest highway in Texas, the 542-mile, two-lane Highway 16 travels through dusty ranchlands, red rock hills, cowboy towns, and the Hill Country’s “Swiss Alps of Texas.”

Utah

Traversing the Grand Staircase-Escalante, Henry Mountains, and Capital Reef Natural Park, the otherworldly geology along 123-mile Scenic Byway 12 doesn’t disappoint with its random arches, “hoodoo” rock formations, and deep-slot canyons.

Vermont

The 51-mile Northeast Kingdom Scenic Byway showcases quintessential Vermont backcountry: hilly farm towns, colorful mountains, covered bridges, and shimmering lakes.

Also check out: The Crossroad of Vermont Byway with panoramic views of and from the Green Mountains.

Virginia

Skip Skyline Drive, swarming with bumper-to-bumper scenery seekers. Southbound from Winchester to Roanoke, the Wilderness Road meanders through the Shenandoah Valley’s historic towns and natural wonders: vertiginous sandstone cliffs, gushing waterfalls, and majestic mountains.

Washington

The 440-mile Cascade Loop encompasses three scenic byways, touring through Washington’s diverse array of ecosystems: Puget Sound islands, open desert, lush forest, craggy alpine peaks, sagebrush lowlands, and cityscapes.

West Virginia

The 180-mile Midland Trail National Scenic Byway offers mountain landscapes; plummeting waterfalls; purveyors of authentic Appalachian craft food, drink, and art; mountain-music venues; and adventure destinations for rafting, spelunking, and fly fishing.

Wisconsin

The 100-mile Lower Wisconsin River Road through the Driftless Area was Wisconsin’s first designated scenic byway. Following the Wisconsin River, it winds around rocky bluffs, through mysterious bottomlands, and into quaint river towns.

Wyoming

Encompassing 162 miles of steep mountain passes and verdant forests, through Grand Tetons National Park and famous Jackson Hole, Parks Centennial Scenic Byway is cited as one of the finest drives in the Rockies.

Stephanie Citron (stephaniecitron.com) is a contributing editor for The Saturday Evening Post.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Maciej Bledowski / Shutterstock

A Millennial Leaves His Phone and Goes into the Woods

On normal mornings, I wake up and immediately grasp my cell phone from its resting spot next to my pillow and Google the previous day’s new Coronavirus cases. At least, that’s how it’s been for the past few months. But when I woke up last weekend, there was no frightening uphill chart to behold, because there was no phone. I rolled over and gazed out at a blur of treetops through a tent screen. I put on my glasses and realized I was looking over a foggy valley, that the camping spot I had stumbled onto late the night before sat on a cliff perfectly situated to receive the sunrise.

When I decided that I would leave my phone behind to disappear into southern Illinois’s Shawnee National Forest for the weekend, my roommate was concerned. “Why would you do that?” she asked. “What if you get lost?” I told her that people don’t get lost in America in 2020. “That’s because they have cell phones!” she countered.

I would hesitate to claim I have smartphone addiction, but I’ve been known to pass hours slumped on the couch, scrolling through yoga videos I might one day try, bruschetta recipes I might make, far-flung destinations I might visit. I’ve lingered a little too long on Twitter during work hours (don’t tell my editor), and there was that one blur of a weekend that was entirely lost to the engrossing Bloons Tower Defense 6 game.

Of course, I’m not alone in my tendency to zone out and fall headfirst into the time-consuming trappings of the device. According to several surveys from 2017, Americans, on average, spend from three to five hours each day on mobile devices. For younger people, the number is even higher. Our collective panic over wasting time on our phones has created space for some savvy panaceas in the private sector. Tech rehabs have cropped up, self-help texts for more mindful phone use abound, and Google has even gotten in on the action with their launch of Digital Wellbeing. The app gives users a rundown of their screen time and offers nanny-style blockers from too much browsing and scrolling.

I wasn’t seeking such a formal tech break, though; I only wanted to test out the cold turkey method for a weekend. So I dug out my backpacking gear from the back of my closet, gathered a few books (Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill), and prepared to realize some long-held plans to visit a jewel of the Midwest: the Garden of the Gods Wilderness. I told my dog Calliope where we were going, and she seemed indifferent.

My loved ones insisted that I at least keep my phone in the car. I could stash it away and keep it turned off, they said, as it could be necessary for an emergency. I was travelling four hours away to an unfamiliar area, and my Prius did have about 550,000 miles on it. I might have something to prove, I thought, but I’m not stupid. I resolved to hiding it in the trunk.

What would it be like, I wondered as I followed my handwritten directions across hilly southern Indiana, to spend a few days with only my thoughts and my dog? On a local radio station, the deejay gave a shout-out to her “Facebook friend of the week” and directed listeners to her page to check out a video she’d posted of a cute animal. I lucked out and found an Ella Fitzgerald CD in the glove box left by the previous owner.

The Shawnee National Forest, stretching across southern Illinois between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, covers almost 300,000 acres. The sandstone cliffs, bluffs, and hoodoos of the Garden of the Gods were created more than 300 million years ago when the region sat on the north shore of an enormous sea. The continental glaciers that carved much of the state into flatlands stopped just short of the Shawnee Hills, allowing these ancient structures to remain intact and providing views unlike anywhere else in the Midwest.

There is also plenty of wildlife — both dangerous and benign — to be found in the forest. Box turtles, raccoons, opossums, hawks, vultures, and squirrels are everywhere. With some bad luck, you might stumble onto a cottonmouth, copperhead, or even one of the elusive rattlesnakes, the timber rattler or the massasauga (all the more reason to refrain from hiking-while-texting). There are black widow and brown recluse spiders as well as the velvet wasp, a wingless ant-looking bug that delivers “the most painful insect sting in the world.” Encountering any of these spine-tingling creatures is fairly rare, however, and dying from any of them is all but unheard of. That’s what I told myself as I marched through the woods in the middle of the night, my flashlight casting quick, darting shadows on the vast expanses of poison ivy.

Since Shawnee is a national forest, it’s free to camp anywhere you’d like, as long as you maintain some distance from trails and waterways. You can often find unofficial campsites where others have constructed stone fire rings and makeshift seating. On the second night, Calliope and I stumbled upon such a spot, and I built a fire to cook ramen while she collapsed nearby and stared at me thinking, what in the hell are we doing here?

What were we doing there?

I had scratched the long-disquieting itch to get away from it all, but at first it seemed I had traded isolation in my home for isolation in the woods. Camping alone, or with a furry friend, is a surefire way to strip down the distractions of daily life and spend time thinking about where you are and where you’d like to be, both literally and metaphysically. Going without a phone is akin to constant meditation, at once trapped with your own thoughts and liberated from the fast lane of the information superhighway.

There has been some research into the effects of “problematic smartphone use”— particularly as it applies to young people and social media. We know that poor emotional well-being and smartphone overuse are often connected, but causation is difficult to prove. A study released this year in Cyberpsychology looked at “FoMO” (fear of missing out) and PSU (problematic smartphone use) as two separate but connected factors affecting emotional well-being. The findings suggest that it can be a sort of a vicious cycle, with negative feelings arising from both “FoMO stimulating online relationships at the cost of offline interactions and physical symptoms associated with excessive smartphone use.”

The study, along with many others, lends credence to something many of us innately understand: when I waste too much time on my phone I feel bad afterwards, and when I feel bad, I retreat to the comfortable, familiar habit of slingshotting angry birds and scrolling through my ex’s gym selfies.

Without a phone, I noticed more of the world going on around me, like the yellow butterfly that landed squarely on my dog’s nose and stayed, flexing its wings, until she shook it off. I noticed the complete silence that overtakes the woods at dusk. It comes right after the birds’ chirping has tapered off and right before the crickets and katydids begin their nighttime cacophony of sounds. I sat and listened, feeling still alone but also incredibly peaceful — the kind of feeling I might be able to define perfectly by whipping out my phone and Googling an antonym for “stress.” The forest offers this to anyone willing to turn off and tune in to the natural world.

Could there be a way to experience this kind of quiet and focus without hiking for hours and pumping creek water through a charcoal filter?

On Sunday, I slept in to some unknowable hour and then packed up my things, planning to make the trek straight back to the car and drive immediately to the nearest store for a sugary canned coffee drink. Calliope and I set off, making our way through the trails we had hiked in on. When we came to a familiar four-way intersection, I consulted the map and continued on a trail that, I was 90 percent certain, would take us back to the car.

After an hour of hiking deeper and deeper into the woods, I realized we were on the wrong trail. It curved around in a disorienting fashion, and led to a steep uphill climb that I distinctly did not recall from the hike in. Then we found ourselves climbing uphill even more, and yet again. Turning around the bend of every curve brought the excruciating sight of more ascending trail. How high could we possibly be going? I thought. It’s Illinois!

Then, we turned a new corner to find a clearing. Approaching it, I saw that it overlooked the valley in which I’d spent the past few days camping. It had to be the highest point in the park, with a view of the forest and even the farmland past it for miles. The dog walked right up to the edge and looked over, and I realized that I hadn’t known for years whether she was afraid of heights because I hadn’t taken her to any cliffs before. She stood proudly before her domain, creating the perfect opportunity for an adorable (hypothetical) Instagram picture. There would be no evidence on social media of the trip: no livetweeting, no 360-degree videos, no deluge of Facebook likes from jealous friends. The whole thing would have to be archived in my own mind.

When we finally found our way back, we were practically crawling to the doors of the Prius. Driving home, I reflected on the merits of “unplugging,” and what exactly the big takeaway could be from such a short vacation from tech. Would I arrive home and immediately revert to my old ways of binge-reading Twitter drama and feeling phantom phone vibrations on my left thigh every 10 minutes? Would I even remember this vacation if I couldn’t be reminded of the beauty of the Garden of the Gods by Facebook Memories in years to come?

What I will remember is the noticeably heightened sense of focus and peace I felt in the woods. If you give up the smartphone for a few days, you might become hyper aware of just how long it has been since you lived without one. But realizing that it is possible can inspire you to take more breaks from your smartphone day to day. Leave it at home and go on a long walk, or pledge to trim down your notifications. You might be surprised by how much you notice when you aren’t always grasping for your phone. And we could all use more pleasant surprises.

Featured image: Shutterstock, by Oleksandr Koretskyi and A-spring

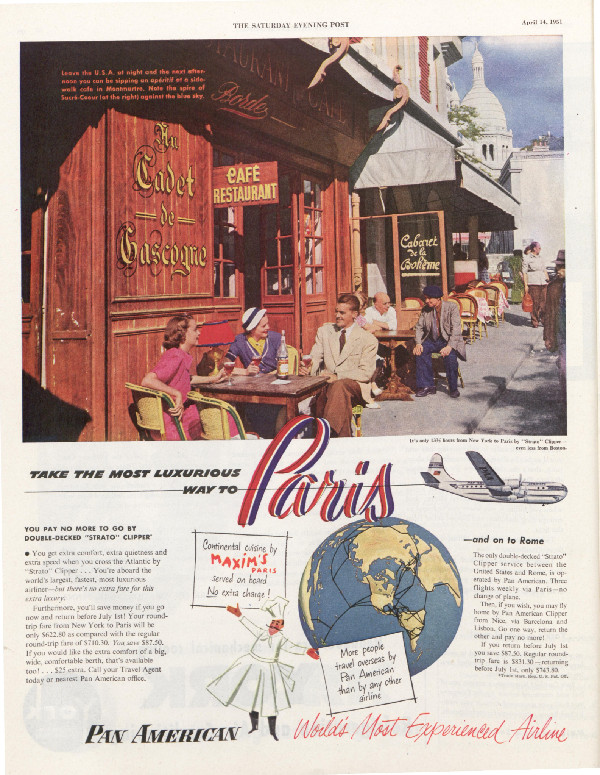

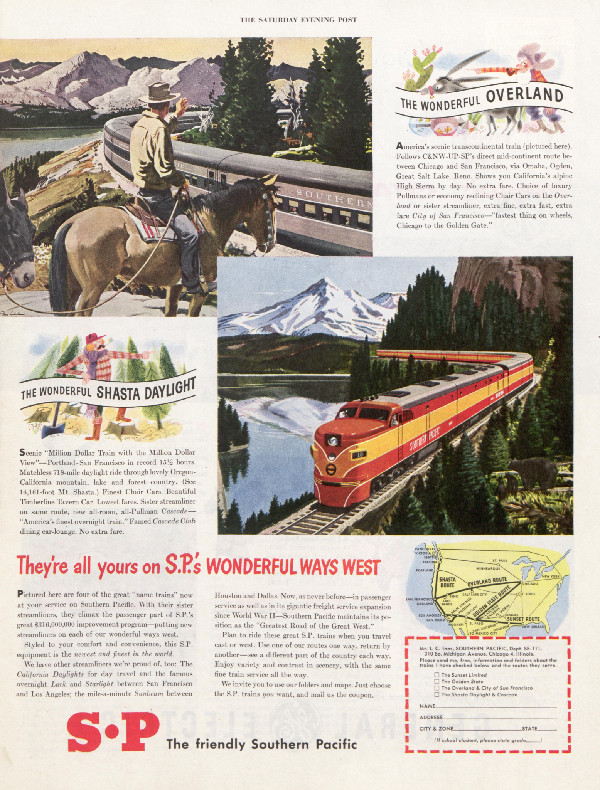

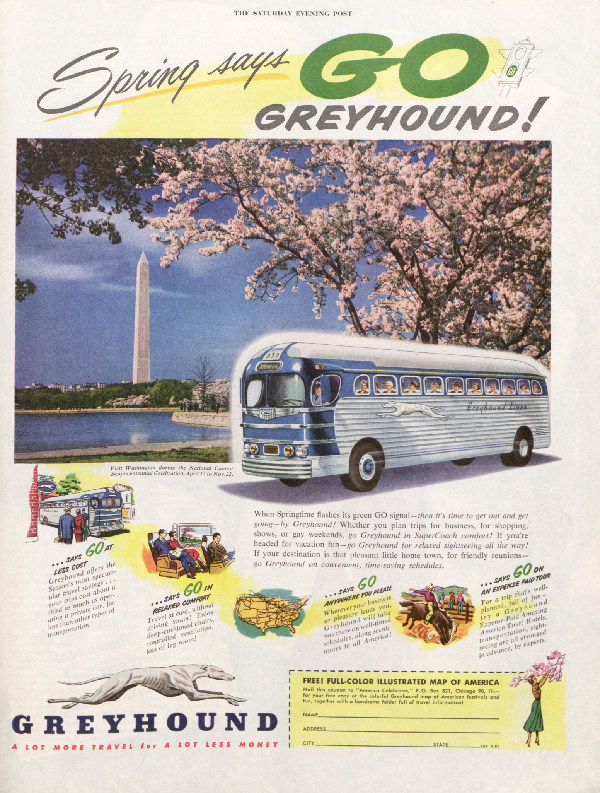

Vintage Ads: Travel in the 1950s

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

March 3, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

April 14, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

November 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

November 18, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

December 1, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

July 1, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

June 24, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 1, 1952

(Click to Enlarge)

October 6, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

Game On! Sunny Weather and Affordable Tickets Make Spring Training in Florida a Winner

For decades, fans have flocked to Florida for a pre-season preview of America’s favorite pastime: baseball. Boasting more than 74 million citrus trees, Florida’s aptly named Grapefruit League squeezes out home runs and plenty of fun from late February through March.

With 15 Major League teams, the Sunshine State is the sweet spot for fans of baseball and saving money. The average cost of a ticket to see the Mets play in New York is $61, but tickets start at $25 to see them play in their spring training facility in Port St. Lucie, 90 minutes south of Cape Canaveral.

East Coast

This spring, West Palm Beach holds the hottest ticket in baseball. That’s because the two teams who share West Palm’s FITTEAM spring training stadium, the Houston Astros and Washington Nationals, both made it to last year’s World Series. The Nationals were last year’s winner, while the Astros won in 2017, the opening year for this rookie South Florida sports complex.

Of course there’s a lot more than just sports to be enjoyed in Palm Beach. The arts are thriving, and a stop at one of the local museums, like Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens or Flagler Museum, is a must. Or take a stroll to gawk at the price tags at the upscale boutiques (think Lilly Pulitzer, Chanel, Gucci) lining Worth Avenue, Palm Beach’s version of Rodeo Drive. Head over to brunch at the grande dame of Palm Beach hotels, The Breakers, for a break from hot dog-and-burgers ballpark fare.

Just 15 minutes north is the northernmost Palm Beach County town of Jupiter, home base for the St. Louis Cardinals and Miami Marlins. Though this sleepy beach town has a population of only 65,000, it’s home to the largest number of professional golfers in the country. With perfect weather, quiet beaches, and magnificent golf courses, it’s no wonder some 35 PGA Tour pros live there, including Tiger Woods.

Take time to enjoy nature by renting a canoe and paddling through the cypress tree-lined waterways of the Loxahatchee River at Riverbend Park, only 10 minutes from Jupiter’s Roger Dean Stadium.

Enjoy the water while dining as well. For a romantic night out, book a waterfront table at the upscale 1000 North. Make sure and ask for a view of Jupiter’s iconic red lighthouse. For more laid-back waterfront dining, head over to Guanabanas, a beloved local hangout known for its live music and casual island vibe.

The Jupiter Beach Resort and Spa is the only oceanfront hotel in Jupiter, making it a great lodging choice. Ride one of the hotel’s free bicycles 15 minutes south to the Juno Beach Pier. A day-long fishing permit at this classic Florida pier is $4 for adults, $2 for kids. Fishing poles, tackle, and bait can be rented on site.

Gulf Coast

Florida’s Atlantic Coast scores with three spring training facilities, but it’s the Gulf Coast that sees most of the Big League action, with teams spread from as far south as Fort Myers up to the Clearwater/St. Pete area.

For Boston Red Sox fans, Fort Myers is a fantasy getaway. Daily direct flights from Logan make it easy to enjoy pre-season baseball at JetBlue Park, known as Fenway South. The Minnesota Twins also call Fort Myers home. Should you want to round out your Fort Myers trip with a little more excitement, it’s a two-hour drive along Alligator Alley to the Atlantic Coast’s Miami or Fort Lauderdale.

An hour north is where the Tampa Bay Rays and Atlanta Braves play. Another 40 minutes north, and you’ve landed in Florida’s “Cultural Coast” of Sarasota, home to a professional ballet, opera, orchestra, ten theaters, and the brand new Sarasota Art Museum. Of course Sarasota’s also home base for the Baltimore Orioles and, a half-hour north, to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Don’t let the pristine beaches and vibrant arts scene of the Clearwater/St. Pete region throw you a curve. It’s also got a winning sports scene, with three Major League teams playing within an easy drive of swanky Sandpearl Resort, located on a magnificent wide stretch of Clearwater’s powdery, white beach. Sandpearl’s on the main drag of Clearwater Beach, where you’ll find hip restaurants, surf shops and the iconic Pier 60 with its nightly sunset party. The Phillies and Toronto Blue Jays play in stadiums twenty minutes from Clearwater Beach. Tampa’s George Steinbrenner Field, 45 minutes away, is home to who else but the New York Yankees.

If you’re game for combining spring training baseball with a trip to Disney World, Universal Studios or other theme parks, the Detroit Tigers play a half hour from Orlando.

For baseball lovers, it doesn’t get much better than this: sunny weather, affordable tickets and the rare chance to get up close with the best players in the Major League. If you’re a baseball fan, you won’t strike out with a spring visit to any of these Florida destinations.

Featured image: Hammond Stadium in Ft. Myers Florida, home of the Minnesota Twins (Evan Meyer / Shutterstock)

Depending on the Kindness of Strangers: Couchsurfing in New Orleans

We arrived at the Lower Ninth Ward around 11:30 at night. Driving over a drawbridge and through a field where bullfrogs and cicadas broadcast a wall of sound to accompany the thick, humid air, it was tangibly clear that we were 800 miles away from home.

Fourteen years ago, the neighborhood was decimated by flooding caused by a confluence of levee failures that occurred when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. Even now, it’s difficult for an out-of-towner to tell exactly where the bayou-adjacent industrial area ends and the neighborhood begins.

When we pulled up to Dustin’s property, it looked familiar from the pictures we’d seen online: a metal-sided house on tall stilts surrounded by a few small cabins and an open air kitchen. My long-time best friend Jill and I looked in from the gate on the sidewalk. Two dogs noticed us and started barking.

One of them was wagging her tail, we observed, but it still seemed risky to enter the gate unaccompanied by their owner. Dustin hadn’t responded to my calls or texts since we’d passed Biloxi. Jill shot me a look of panic that said, We are going to sleep in a bed under a roof tonight, right?

Then, we lucked out. A woman pulled up in a Jeep and let us in the gate. “I don’t live here,” she said, “but I’ll get Nate to show you around.”

Nate told us we were welcome to use anything in the kitchen (coffee, spices, produce saved from nearby grocery store dumpsters), and he showed us the A-frame cabin we would be sleeping in. “Dustin told you we don’t have plumbing, right?”

He hadn’t mentioned it. We’re a low-maintenance pair, though, so an outhouse wasn’t a deal-breaker. Plus, we were crashing with perfect strangers for free.

For the last ten years, I’ve been couchsurfing just about every time I travel. I’ve stayed with (former) strangers in Washington, D.C., Boulder, Nashville, Paris, Ljubljana, and Budapest. They’ve cooked for me, explained local history, given me beer, and even changed my mind on big philosophical questions. I’ve also hosted couchsurfers at my own home and offered all of these things to other travelers. In addition to providing a free method for staying in cities around the world, it has given me a renewed perspective on humanity and our capacity for meaningful association.

Couchsurfing works similarly to a social media site. You create a profile (as a host or a couchsurfer or both) and request to stay with someone. You can scan users’ interests, see what their house looks like, and read reviews of others who have hosted or stayed with them.

When I bring up Couchsurfing to people, their concerns often focus on one possibility: murder. What if someone is only pretending to be a gracious host so that they can have the perfect opportunity to slit my throat while I’m asleep on their hideaway? The truth is that people have been murdered by psychos posing as well-meaning couchsurfing hosts, but it doesn’t happen nearly as often as you might imagine. As Jill and I slept in our humble cabin, we were more worried about mosquitoes, fire ants, or the possibility of a copperhead greeting us first thing in the morning.

As it turned out, we were greeted instead by coffee and a refreshing outdoor shower. The Louisiana sun got hot fast, so we quickly planned an afternoon of visiting St. Louis cemetery (the free one) and grabbing some po’ boy sandwiches. Against some local advice, we also paid a short visit to the French Quarter. What kind of person would visit New Orleans and ignore it? We wandered through the quarter not in search of an “I PUT KETCHUP ON MY KETCHUP” t-shirt, but to day-drink and take in the ubiquitous wrought-iron balconies draped in ferns.

Strolling down Bourbon Street and sipping Paradise Park and Dixie beers, it occurred to us that we hadn’t yet met Dustin, our host. He was working that morning as a pedicab driver, but he assured us he would be home in the afternoon. We resolved to return to the Lower Ninth Ward before hitting Frenchman Street that evening.

When we got back to the property, Dustin was flossing his teeth in the front yard while a few neighborhood kids wrestled with his dogs. He was shirtless, wearing his hair in a messy mullet, and we asked him about the process of building his anarchist paradise. He had come from Austin as a trained carpenter with a camper trailer, and he slept in it while constructing a fence, outhouse, kitchen, shower, two cabins, and — eventually — a house. I hadn’t had the opportunity to utilize the outhouse yet, but of course I was wondering where, exactly, it all went. Dustin explained his rigorous routine for composting human waste, a system I’d only ever read about before. Given the risk for pathogens, it needs to sit much longer in higher heat than other compost. Living this way isn’t unheard of, but surely rare in a metropolitan area.

Who are these people? You might be asking yourself. Nomadic hippies and communist cat ladies? Well, some are, presumably. But the platform is filled with all kinds of people. A common tendency of couchsurfers — besides an interest in world travel — seems to be a desire to live out a reaction against the isolationism of modern living.

In the South of France, I couchsurfed with a chef in his small “sustainability hut” in the foothills of the Alps. We drank rum and played dominos into the night, listening to music from the only source of electricity: a small, solar-powered battery. When it came time to go to bed, he led me into the singular queen-sized air mattress in his cabin that I hadn’t yet considered we would be sharing. I took a side, and he scolded me: “Take off your clothes! They’re dirty!” So, I stripped down to my underwear — regretting my faux pas — and he did the same. We bade each other “goodnight” and slumbered peacefully amid the sounds of the Riviera night.

That might be a radical example of anti-isolationism, but couchsurfing offers subtler ways to break from the privacy of travel and expose yourself to possibilities that would never present themselves otherwise. You can cook a meal with a local, stay in a neighborhood out of the way of hotels and overpriced restaurants, and discover the hidden gems of a city. The irony of couchsurfing is that, as a social media platform, it actually encourages unconditional face-to-face interaction. Although the website hosts a database of user information and geographical algorithms, most of what defines couchsurfing takes place in the real world without any prospect of profit.

In 2009, the year Couchsurfing’s membership hit one million people, a startup in San Francisco launched a similar application called AirBnB. The primary difference between the two websites was that, on AirBnB, hosts could rent out a room or apartment for actual money instead of warm company.

Since then, AirBnB claims it has ballooned to around 150 million users, while Couchsurfing sank to 12 million last year. The wild years of hitchhiking and traipsing around bars with strangers were fun, as I’ve heard from more than a few former couchsurfers, but these days many would rather have a guaranteed place to stay with clean sheets. You can’t blame them. But, still, the omnipresent “sharing economy” seems to lack the soul of its predecessor, the lesser-known, digital “gift economy.” Some experiences can’t be bought, or, at least, not in the same way.

I’ve used AirBnB (once), and it was fine, but it lacks the delicious risk of couchsurfing. Even if an AirBnB’er does meet their host, the interaction lacks the naked humanity and emotional stakes that come with good old benevolence. Don’t you want to meet the person who lets people sleep over just for the heck of it?

According to the website, the values embodied by Couchsurfing are generosity, connection, kindness, etc. So, like Burning Man or Mayberry, the community is predicated on the idea that people are generally “good.” I’m not settled on that conclusion, having witnessed others cheat on their partners, steal booze, and treat people poorly. But I have found that people are endlessly complicated and interesting, and Couchsurfing acts as a fast lane to find that out.

One morning, I went for a jog around the neighborhood. The north end of the ward seemed as though it never recovered from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. The sidewalks ended erratically, mattresses and old TVs sat junked in the street, and entire blocks of housing lots sat empty, growing dense flora around old foundations.

Jogging south, the neighborhood perked up considerably. Colorful, modern homes with dramatic, jagged angles lined the streets as though they had risen from the earth after the floods receded. One of these houses, just a block and a half away from Dustin’s house, was posted on AirBnB for $195 a night. If I wasn’t committed to a spontaneous lifestyle of radical trust in strangers, I could have paid for more reliable lodgings on the same street — plus air conditioning, indoor bathing and cooking, and Wi-Fi. But where’s the fun in that?

Featured image by Jill Young, edited by Amy Tackitt

Some names have been changed.

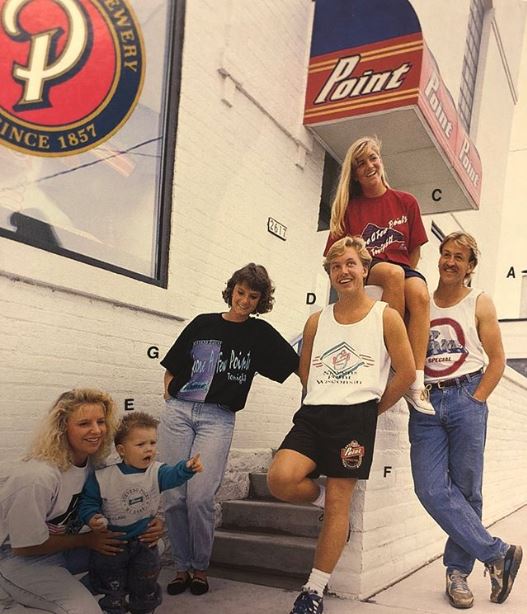

Summer Road Trips: The Oldest Craft Breweries in the Country

American beer has gone through a transformation in the last 30 years. Wherever you are in this country, you’re bound to be about 15 minutes from at least one craft brewery. Everyone and their brother-in-law seem to be brewing small batch IPAs these days, but these are the old-timers who started the trend.

D.L. Geary Brewing Company

Proudly bearing the title “New England’s First Craft Brewery,” Portland, Maine’s Geary Brewing Company got into the craft beer game ahead of the curve. More than 30 years ago, Karen and David Geary began brewing their signature pale ale after David learned brewing techniques with the help of a Scottish nobleman. Today, dozens of breweries make up Portland’s beer scene.

Boston Beer Company

As the story goes, Jim Koch found his great great grandfather’s Boston lager recipe in an attic in the ’80s and started his craft beer empire. Koch’s business acumen skyrocketed the Samuel Adams brand into a household name. The company’s Boston brewery sits in the old Haffenreffer Brewery, an 1870 facility in Jamaica Plain that earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition to their classic brewery tour, Boston Beer also offers exclusive tours into the barrel room where patrons can get a closer look at the fermentation and aging processes and try pairings of Belgian-inspired brews with chocolate or barrel-aged beers and cheese.

Yuengling Brewery

America’s oldest brewery will be celebrating its bicentennial in ten years. Richard Yuengling, Jr. is the fifth generation of owners to run his namesake brewery in Pottsville, Pennsylvania. They still make the lager and porter that “Eagle Brewery” boasted for their “purity” and “cleanliness” in 1829, when it was sold to local coal miners. When you visit their historic site, you can enjoy a lager in their Rathskeller bar then jaunt down the road to get some Yuengling’s ice cream. It’s the (now unaffiliated) ice cream business that helped D.G. Yuengling & Son survive Prohibition.

Frankenmuth Brewery

The dachshund mascot “Frankie” has graced beer labels and truck sides for this historic Michigan brewery since the 1930s. The Frankenmuth Brewery itself has been around for even longer — since 1862 — situated in the small city of Frankenmuth along the Cass River. “Michigan’s original microbrewery” has had its share of hardships over the decades, from fires to tornados, but they still manage to turn out 36 different styles of beer, many of which have taken home awards at international competitions. When you’ve had your fill of beer, the world’s largest Christmas store is just down the street.

Stevens Point Brewery

Wisconsinites have been enjoying Point Special lager since 1857, and the brewery even served it to troops fighting in the Civil War. It only became available to beer drinkers outside the Badger State in 1990; in 2003, the lager won the gold medal at the Great American Beer Festival. The company prides itself on being Wisconsin-owned again after years of changing hands, and a walking tour of the brewery will afford you a close look at how their brews are made, aged, and packaged.

Minhas Craft Brewery

Though it’s gone by many names — Monroe Brewery, Blumer Brewery, Huber Brewery — the Minhas Craft Brewery, now owned by Canadian siblings Manjit and Ravinder Minhas, has been around since 1845. During Prohibition, the Monroe, Wisconsin facility even made ice cream and Blumer’s Golden Glow Near Beer, a nonalcoholic brew. The offerings at Minhas nowadays might deviate from your typical expectations around craft beer (they make Boxer lager and Axehead malt beverage), but a visit to the historic brewery offers the chance to see a large collection of 19th century brewing machinery and advertisements housed in an on-site museum.

Abita Brewing Company

Beer from this Louisiana brewery can probably be found at a bar near you, since they distribute to almost every state. Abita attributes the clean taste of their beer to the source of the water they use, the artesian wells of Abita Springs. The bayou brewery also makes root beer and cream soda using Louisiana sugar cane. Just a short drive from New Orleans, this small-town stop offers beer lovers a taste of some of the first inventive brews in the south.

August Schell Brewing

August Schell founded his brewery (and his town of New Ulm, Minnesota) in the mid-19th century. The grounds of this historic property feature roaming peafowl, gardens, and a brick and stone mansion, built by Schell in 1885. The brewery has been passed down in Schell’s family since the beginning, and, in 2002, they acquired the beloved Grain Belt Beer.

Sierra Nevada Brewing Company

See where one of the first — and still among the most acclaimed — American Pale Ales was born. Ken Grossman opened his brewery and first brewed the iconic Sierra Nevada Pale Ale in 1980. Since then, the company has become known for sustainable practices like composting, CO2 recovery, and solar power. The Chico, California location is where the brewery picked up steam (hence the name), but Sierra Nevada opened a second operation south of Asheville, North Carolina in 2012.

Hale’s Ales

In 1983, Mike Hale opened his Washington brewery, a beacon in the formerly pale ale-less Northwest. Now, the Seattle operation offers a variety of flagship and seasonal brews, and they’ve turned their warehouse into a seasonal event space that hosts music festivals, standup comedy, and dance parties.

Post Travels: Exploring California’s Striking Big Sur

It’s the type of drive road trips are made for. Along California’s central coast, Highway 1 twists and turns its way through Big Sur, awarding those behind the wheel with spectacular views of rugged coastline and sandy beaches. The two-lane road is narrow but as this video shows, leads the way to waterfalls, wildlife, state parks, and unforgettable scenery.

See more Post Travels.

Post Travels: Chase the Northern Lights in Fairbanks

Seeing the northern lights, also known as the aurora borealis, is something many folks dream about. But freezing temperatures, long airplane flights, remote locations, and predicting Mother Nature’s whim can put a damper on even the most enthusiastic travelers’ plans.

But what many don’t realize is that one of the best locations for viewing the northern lights is located in the United States. Aurora Season runs from August 21 through April 21 in Fairbanks, Alaska, meaning there are plenty of nights you can watch the lights dance through the sky when there’s no snow on the ground.

A Taste of Alaska Lodge

Just a 20-minute drive from Fairbanks, family-owned and operated A Taste of Alaska Lodge offers easy access to the city, while still boasting a remote location that makes you feel as though you’ve ventured into the Alaskan wild. Set on 280 acres, on clear days it serves up brag-worthy views of the Alaska Range. Once the sun sets, it’s an ideal location to watch the northern lights blaze through the sky. And with only eight rooms in the main lodge, and three separate cabin-like structures on the property, you practically have the sky to yourself.

The best spot to view the aurora borealis is from an open field behind the lodge. Chairs are scattered about for folks to relax while waiting for the lights to appear. A heated yurt provides a spot to warm up and socialize with fellow watchers. Guests that head back to their room often find it difficult to venture out again. Rates from $195.

Borealis Basecamp

One look at Borealis Basecamp, and it’s hard not to get excited. Six white domes each boast a wall made of windows, precisely positioned so you can curl up in bed while watching the northern lights. Set on nearly 100 acres of boreal forest, domes have king beds, a kitchenette with small refrigerator and sink, and a bathroom with sink, stall shower, and dry flush toilet. Powerful heaters keep domes toasty, but keep your shoes by the door. It’s next to impossible not to run outside when the aurora appears. Borealis Basecamp is about a 45-minute drive from Fairbanks. Rates from $339. A two-night minimum stay is required. (Four more domes are currently under construction.)

Chena Hot Springs Resort

A bit more than 60 miles outside of Fairbanks, Chena Hot Springs Resort requires the longest stretch of time behind the wheel, but there’s plenty of incentive to make the drive. As the name implies, natural hot springs averaging 106 degrees Fahrenheit are open for soaking daily from 7 a.m. to midnight. Even during summer, guests searching for an Alaskan chill can visit the onsite Aurora Ice Museum. Kept at a cool 25 degrees Fahrenheit, it’s home to a handful of rarely used guest rooms, sculptures, and a bar that pours strong Appletinis. Those hoping to see the northern lights can make the short walk to the property’s heated Aurorium or book a tour to a remote spot near Charlie Dome that boats panoramic nighttime sky views. A heated yurt is well-stocked with warm drinks and snacks. The bumpy ride up to the viewing point, in the back compartment of a unique off-road vehicle, helps keep travelers awake and alert. Eighty rooms with rates from $210.

Post Travels: Family-Friendly Portugal

Traveling with kids presents a unique set of challenges. Break away from some of the more traditional family-centric locales and it’s even easier to feel overwhelmed long before any flight gets off the ground. Encouraging families to venture outside of their travel comfort zones, Global CommUnity works to highlight the sometimes unexpected family-friendly side of destinations around the world. From the sidecar of a vintage motorbike, to a highspeed boat ride along Lisbon’s Tagus River, to a horse-drawn carriage ride through the palace spiked UNESCO World Heritage Site of Sintra, as this video shows, Portugal gives families plenty of reasons to pack their bags and come for a visit.

See more Post Travels.

Cold Comfort: My Night in an Ice Hotel

We’ve just left a fine room at the Fairmont Le Château Frontenac, a grand hotel in Québec’s quartier historique, and we are driving on a dark country road. It is 20 degrees below zero Celsius (–4 degrees Fahrenheit). We are on our way to the Hôtel de Glace, the Ice Hotel, full of excitement and dread.

“It’s not that bad in the rooms; just minus five,” a waiter told us a little earlier as we had our last meal before departing. Then he added, reassuringly, “You don’t really feel it. It’s a very dry cold.”

The taxi driver, a francophone Québécois, doesn’t speak much English. “I hope you have a freezing night!” he says after I pay our fare. I think he means it in good spirit, that this is what you’re supposed to say when people are going off to sleep in a modern igloo, the way theater people say “break a leg.”

The path to the hotel has patches of black ice. A million stars look frozen in space, and it is so wondrous it could take your frosted breath away. But your breath comes out in white puffs, like cartoonist’s thought bubbles that say, “… boy, it’s so cold I can’t even think of something funny to say.” At this moment the cosmos seems considerably less miraculous than central heating.

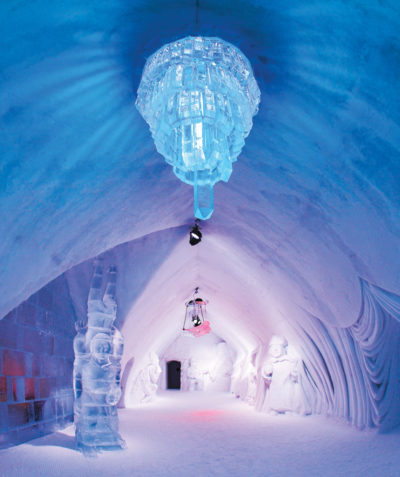

Every kid, I suspect, at some stage wishes to sleep in an igloo. The Hôtel de Glace is a whole complex of them, interconnected halls and chambers cut and carved from 30,000 tons of snow and 500 tons of ice. There’s a chapel with an altar and pews, a bar, and a room with an indoor ice slide. Another space is a gallery of whimsical ice sculptures: an old-fashioned landline telephone, an enormous volume like a Gutenberg Bible, and a vintage deep-sea diving helmet. There are whole dogs and a giraffe’s head and neck sticking out of the floor. A 600-pound ice chandelier with long ice pipes hangs from the ceiling.

The 45 guest rooms come in a variety of shapes and dimensions. Ours, the Snowflake Room, has walls carved with patterns that suggest magnified snow crystals. Queen-size mattresses are on two platforms made of ice. A pedestal and two chairs on either side of a table are fashioned, of course, out of ice.

The Hôtel de Glace would melt on its own, but due to concerns of insurers, they bulldoze it each spring. It takes 15 artists and 35 workers six weeks to create it anew every winter, and it’s open from early January until late March.

The complex has colored lighting that keeps refracting through the ice and settling on the snow like Technicolor dust. The other visitors, mostly Canadians, are a merry crew. Québécois are big on EDM (electronic dance music), even when they’re wearing snow pants and parkas. I admire them for it. When I put on clothes like that I’m even stiffer than usual. They dance on the glazed surfaces of the ice bar and pose for photos with frozen smiles around a flaming chiminea. The hotel brings out blocks of ice and little picks for a sculpting contest. People chip away, making little snowmen or ice hearts.

We go to the spa, which has hot tubs and saunas, and change into bathing suits and robes in a conventional building located behind the ice complex, where there are also toilets, showers, and lockers. The hot tub’s submerged lighting catches the steam hovering just above the water’s surface. We take off our robes and plunge like soldiers into the safety of a trench.

This is all a game of catch with the cold: First it has you, and then you escape by slipping into the hot water, and you lie back looking at the stars and enjoying the hot water and the jets from the Jacuzzi. Strangers want to know where you came from. You’re like brothers in arms facing the same adversaries. Cold hands, warm hearts.

Then it’s time to get out, because you know you can’t stay there all night. There’s no escape. The cold has you from the bottoms of your feet as they touch the icy floor to the top of your wet head. It licks your raised, weeping flesh.

And you give it its taste on your way to dry off and change clothes and get ready for the main event: sleeping. We return to our Snowflake Room and twist ourselves into the sleeping bag liners and stretch our limbs into the mummy bags. I am glad for the advice we received on arrival. For example: put on fresh socks. If you wear the ones you sweated in already, the cold air will circulate and your feet will get colder all night.

The liner works beautifully. There is, I’m sure, some science to this, something about airflows and trapping heat between layers. But what you need to know is that what starts out warm and dry stays warm and dry, and that when the warmth surrounds you, it feels a lot like complete love, the kind of all-enveloping peace you last experienced in the womb.

There is, though, a kind of low-intensity anxiety. Fear, for one thing, that the warmth won’t keep and you’ll wake up freezing. And fear, for another, of not sleeping, of an eternal dark night shivering and shaking like a detox patient. But cold exhausts the body and fear exhausts the brain, and soon enough your wife taps you to complain: You’re snoring.

An arm falls out, and the cold air coats it. Breathe through the nose and the air freezes your nasal passages, and you wake up with apnea; breathe through the mouth, you get a dry throat. I fall back to sleep. The ski hat I brought along comes off, and some arctic spirit massages my head and breathes on the rims of my ears. I twist in my mummy bag to reposition. The bag is rated for 28 below. Eventually it gets to -26. That’s the temperature outside, of course. Inside I have no idea. I suspect it’s getting colder all night, but it’s possible I’m just weakening, waves of cold battering the ramparts of my being.

I’ve slept outside, exposed to the elements in deserts and jungles, and I’ve been in a few really grim hotels, too, but now it comes as a revelation that I am, in reality, a soft man.

I dream of the hours of the night. I dream that it’s morning. Even so, unlike a few guests who bail each night, the one thing I wouldn’t dream of doing is running for

heated shelter. I’d rather be mummified by frost, a stiff on my bed of ice, than to have quit. I have my pride.

In the morning, light pours in through the hole in the ceiling that’s there for ventilation. Light is not just illumination. It brings news: I have survived. This is a modest achievement. I think of the great polar explorers, Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton. They had to melt their sleeping bags before climbing into them. The biggest advantage a modern adventurer has today, a modern adventurer once told me, is not GPS or satellite phones but technical fabrics and advances in footwear.

I lie there a while, enjoying the soft light and serenity, and also girding myself to the idea of unzipping the bag and climbing out. In the end, it isn’t courage that makes me move but a full bladder.

I get up quickly, jiggling a foot into a shoe, careful not to land an unshod hoof on the snowy floor, and give my stiff spine a fillip. Then I stand in a series of shivers and spasms, like a foal getting itself upright, and, pulling a jersey over my swollen dome, I shuffle forward and lurch toward the finish line: a hot breakfast, indoors.

Todd Pitock’s last piece for the Post was “The Healing Power of Baseball in Japan” (March/April 2018), which won an award from the American Society of Journalists and Authors.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Post Travels: The Beauty of Armstrong Woods

Visitors to the San Francisco Bay Area flock to Muir Woods National Monument by the carload. But for those willing to venture a bit father to the north, Armstrong Woods State Natural Reserve quietly awaits. Located in Sonoma County’s quirky city of Guerneville, there’s no need to reserve parking or book a shuttle. As this video shows, depending on the time of day, you could have the towering grove of redwoods — many growing before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock — practically all to yourself.

See more videos at www.SaturdayEveningPost/Video.

Post Travels: Fall in Denali

Fall in Alaska is fleeting. The weather is unpredictable. Autumn colors and the mountain views they frame on clear days are photo worthy, but the real prize for travelers this time of year is the wildlife that calls Alaska home.

While traveling with a small group tour from John Hall’s Alaska, I had the opportunity to visit Denali National Park & Preserve. Bears, moose, caribou, and even a porcupine, popped up alongside the only road into Denali, as I slowly made my way 92 miles through the park to the end of the road where Kantishna, a gold mining camp was founded in 1905. Most of Denali Park Road is open only to bus traffic. Days spent exploring are long, but as this video shows, well worth your time.

See more videos at www.SaturdayEveningPost/Video.

7 Online Travel Guides to Help Make the Most of Your Next Trip

By now, you’ve probably realized that there are a lot of online options for buying plane tickets, booking hotel rooms, and finding your way around a new city. But what about figuring out exactly what to do while you’re there? In ages past, travelers would go to a local bookstore to pick up a paperback destination guidebook. You’d spend some time dog-earing pages and circling interesting items, and then hope that the information wasn’t outdated by the time you actually arrived.

Now, the internet provides a plethora of travel information to help you not only find the best deals but also discover the amazing details that can really make your travel experience one to remember. These seven websites can help you find the best places to shop, the most interesting enclaves off the beaten path, or the most unusual activities once you’ve arrived at your destination.

1. Frommer’s

Frommer’s has been one of the most popular travel guides since the 1950s, when the company released the classic Europe on $5 a Day. Now in addition to its print guidebooks, Frommer’s has an extensive website offering all sorts of tips and ideas for traveling around the world.

If you already know where you want to go, start with the Destinations tab, where you’ll find an impressive amount of details about a wide range of locations. Each destination entry essentially has an entire guidebook’s worth of information at your fingertips. Not sure where you’d like to go for your next vacation? Try the Dream Trip Recommender, an interactive page where you can select options and choose how important various aspects like luxury, culture, food and drink, and nightlife are to your choice. The website will then suggest options that might fit your requirements. The Trip Ideas and 100 Family Trips tabs also offer suggestions for places to go and things to do with your next chunk of free time.

2. Fodor’s

Fodor’s is the world’s largest publisher of English-language travel and tourism information. With hundreds of guide pages highlighting top destinations around the world, each location entry features an overview of sights, restaurants, hotels, entertainment, shopping, activities, and travel tips. A section called Fodor’s Choice highlights some of the most interesting options and a brief primer on the language spoken in that location. Fodor’s also includes extensive information about hotels, restaurants, and cruises around the world, and for the somewhat more budget-conscious, the Deals section lists some of the more affordable options.

3. Lonely Planet

Lonely Planet is the largest travel guidebook and media publisher in the world. Aimed at backpackers and other budget travelers, it offers both standard tourist information and a hefty offering of destinations and options off the beaten path, letting travelers explore the real countryside outside the typical souvenir shops and well-worn photo ops.

Lonely Planet offers hundreds of articles about everything from Europe’s hidden gems to a guide on packing light. If you want a more personal web experience, the Thorn Tree Travel Forum is touted as the oldest travel community on the web. There, you can chat with other travelers to get advice and ideas about everything from getting a good latte in Lesotho to traveling through Tibet.

4. Rough Guides

Like Lonely Planet, the Rough Guides guidebooks were originally marketed to low-budget backpackers, though Rough Guides has now expanded to include travelers on all budgets. Containing information for hundreds of destinations, Rough Guides helps you plan your trip with tips about accommodations, restaurants, sights not to be missed, and tips on when to travel.

An ever-expanding library of articles about everything from local festivals to trips for first-time travelers will help whet your appetite for adventure, and a photo gallery features gorgeous images from around the world. You can also purchase hard copies of specific guidebooks, phrase books, pocket guides, and maps.

5. Rick Steves

Travel aficionados and lovers of public television are probably already aware of Rick Steves, the eternally cheerful travel writer, host, and tour guide whose Europe Through the Back Door series is incredibly popular. As the title implies, the books and website focuses on travel in Europe, including destinations from Scandinavia to Turkey.

A large library of travel tips and articles helps even the most nervous traveler feel confident traveling alone or with a group, and the website’s Graffiti Wall is a huge online community of travelers eager to share their experiences and advice. Articles about individual cities, regions, and entire countries can be found in the Plan Your Trip section, offering invaluable advice and suggestions.

6. Let’s Go

The Let’s Go series is unique in that it is entirely researched, written, edited, and run by students and was the first of the budget and backpacker travel guides. In addition to the usual information about tourist sites, accommodations, and restaurants, you can also find details about hostels, travel deals, and “beyond tourism” options such as volunteer or temporary work opportunities.

Personal stories from travelers young and old can be found under the Stories tab, offering tantalizing glimpses into some of the most unique destinations on the planet. Recent posts include “24 Hours in Norway” and “Desert Wanderings of a Solo Female Nomad” — sure to get your travel itch going.

7. WikiTravel

Following the model of Wikipedia, WikiTravel aims to create “a free, complete, up-to-date, and reliable worldwide travel guide.” With almost 26,000 destinations currently in its database, it’s certainly well on its way. Most entries start with a section of general information and include details like getting to and around the destination, languages and currency, tourist destinations, food and drink, and culture.

Much like its larger sibling, WikiTravel is an easy website to get lost in. You’ll find yourself clicking link after fascinating link as you explore the world full of options. Since this is such a dynamic, user-created community, you can also be assured that information is probably even more timely and up-to-date than that coming from publishers that have to wait until the next publishing cycle to update their guides.

Know before you go

While there’s something to be said for heading out and going wherever the road takes you, it’s generally a good idea to have some sort of plan in mind before venturing into the great unknown. Whether you’re a backpacker looking for an inexpensive trip to the wilds of South America or a family interested in exploring the arts and culture of Europe, you may never need to purchase another guidebook again if you first spend some time exploring these websites!

This article originally appeared on Tecca. More from Tecca:

Travel Tech Guide: How to travel well with technology

Stay Green: 11 hotels that’ll help save the earth while you travel it

Travel gadgets, sites, and services to save money, time, and a whole lot of hassle