We Become Nothing

We got off the bus in Göreme and found a room in the Kervansaray Otel. I was sick. The Kervansaray’s owners, a father and son both first-named Kemal, were troubled by my presence, alone, when Luke left. He said he was going to find me some crackers and bottled water, but he was gone for what seemed a very long time. We were the hotel’s only guests.

The Kemals walked up and down the hallway, checking on me. I lay shivering and burning up in bed and being sick into a T-shirt because I didn’t want to go past them to the bathroom. I watched their shadows against a sheet of textured gray plastic in the corridor wall. That plastic was compensation for having no window to the outside; it let some light in, but it also trapped me in place because I couldn’t hide. I even saw one Kemal bend down to peer through the keyhole, which was the old-fashioned kind with a big gap. I was sure they thought there was something wrong beyond the usual illnesses that seize tourists, and knowing that they suspected this made me feel guilty, even though I had done nothing.

The Kemals were relieved when Luke came back and took charge of me. I was relieved too. His breath smelled like sesame seeds. I rinsed my mouth with the bottled water he’d brought me.

“Better,” I said. “Better.”

The Kemals fetched glasses of tea for both of us. We stood in the plastic-lined hallway and drank politely, smiling warily at each other.

Luke and I had already had tea all over Turkey, given us by hoteliers and merchants and, yesterday, an elderly couple in Ankara who beckoned us into their plywood shack during a sudden snow flurry. Their çay might have been the reason my stomach was churning now, or at least part of the reason. I’d also eaten some carrot shavings with a kebab, though I’d been warned that fresh vegetables were dangerous. I thought I’d been to worse places and had ingested dirtier things.

When our glasses were empty, Luke did not want to stay inside. “Let’s take a walk,” he said. “Get you some fresh air, see the sunset. There are caves up the hill.”

“I don’t know how far I can go,” I said. Having him back and drinking some tea had settled my stomach a little but not enough.

The Kemals encouraged us. The son said, “The path is called Hill of Dreams.” The father said, “Some peoples lives in the caves.”

We had come to see the underground cities and bright-painted cave churches, jewels of Cappadocia. We hadn’t come to lie sick in hotel rooms by ourselves. So I changed into a long skirt and my last clean shirt, and I tied a scarf over my dirty hair.

“Good-bye,” the Kemals called after us in English. “Good-bye, good-bye!”

The hotel was on the edge of town. Luke and I walked up the Hill of Dreams, toward a giant silhouette of Atatürk done in black wire. His portrait was everywhere because he was the father of modern Turkey. We found a rock that would let us gaze through Atatürk to the sunset, and Luke took off his sweater and folded it for me to sit on. He put his arm around me in that way the guidebook told us not to do where we could be seen, and we leaned into each other.

On this trip, we had been highlighting Rumi’s poetry: The wound is the place where the Light enters you. And Your task is not to seek for love but to find the barriers that you have built against it. And Become nothing, and he’ll turn you into everything.

We were ready. To become everything, because we knew how it was to be nothing. We were making ourselves into new people in a place where almost all temptation was banned. Military police strolled the city streets in olive fatigues, and we were constantly afraid of being arrested. We knew that we hadn’t yet shed that wild-eyed, hungry look of people on the brink. We also knew that if you’re in the habit, you always know where to find more. Miles and miles of poppy fields stretched across the interior.

There were no police on the Hill of Dreams. It was the most alone we had been since landing. Luke kept a casual hold of my shoulders as if I did not need him to prop me up, and I tried very hard not to be sick.

When the sunset began to edge the clouds yellow and pink, Luke reached in his pocket and dropped a box into my lap. It was covered in coarse red velvet and it looked to me like a small, bloody animal.

“I found it in the village this afternoon,” he said. “When something is perfect, you don’t wait.”

What should a person say to that? “We agreed on a year.”

Luke misinterpreted. He said, “Don’t think you aren’t lovable, because you are. By me.”

We had been told that my insecurity was as big a problem as any other addiction. I wasn’t sure I believed that, but I was insecure enough not to question it. On this trip, Luke had given me some encouragement every day, usually in a way that reinforced a bad feeling: Don’t think you aren’t lovable felt like Nobody but me will ever love you. I supposed he would promise something like this in his vows.

“Go on, look inside!” Luke picked up the box and was about to open it himself when a coincidence came along.

An old man, or possibly one in late middle age, shuffled quiely up the path with a steadiness that must have come of a lifetime treading unstable ground. He wore a black fez and pants baggy to the knees, with a long, once-white shirt. Everything about him was loose and thin and barely held together.

I shrugged my way out of Luke’s embrace; I didn’t want to offend with public touching. But the man did not look at us. He came very close, yet kept his face pointed forward.

At first I was glad for the interruption, and then I was gladder when he stopped a few yards up the path. He made a clicking sound and flicked his fingers toward his body.

“Let’s go,” I said. I handed the box back to Luke. It was unlike me to be so impulsive, but I wanted to be anywhere the proposal was not.

Luke was torn. He mumbled, “I think I saw that guy in the village today. He was at a café or something.”

Anytime Luke was vague, I worried about what he did not want to tell me. He didn’t seem to have the same concerns about me, and that worried me in a different way.

Up ahead, the stranger waited. He flicked his fingers toward himself once more.

“Come on,” I said, “when are we ever going to meet someone like him again?” Even the old couple in Ankara had worn T-shirts, and they had a television.

Luke put the box back in his jeans. “Okay.” He helped me stand and we followed the stranger. It was good to be moving around, though I felt wobbly.

The man led us to a slope of crumbly karst, onto which he stepped as lightly and surely as a carpet. I hesitated. The slope was steep and I was tired from being sick; there was a perfectly good path we could have taken instead.

I tried out the languages of which I knew a little: “Français, Deutsch, español, English?” I wanted to ask about the path. “Yok?” I finished. No, nothing?

He didn’t answer. Luke took a step onto the karst, slid down, stepped up again, and held out his hand. I didn’t want this adventure anymore, but I felt I had to go too, since I had started it.

In this circumstance, it was all right to touch. We held hands and slipped and skidded, but our guide barely dislodged any pebbles.

It would be natural to seek one of Rumi’s lessons here, in the accidental encounter, the silent old man passing lightly through life. I tried. I was tired but I tried because I really wanted to believe that all of this meant something. I still didn’t feel great.

Luke pulled me the last few feet, onto a flat, terraced area. Incredibly, what we saw was worth all the effort. An old red-and-yellow wooden cart was parked there with a couple of goats tied to its wheels, and a handful of women in dark skirts and headscarves sat on the edge of a well, smoking cigarettes. They were surrounded by skinny cats twitching their tails like dogs. Behind, the cave mouths expanded as the sky colored orange. It was a picture from a fairy tale, a scene printed on brochures to lure tourists.

And it was here that our host at last showed his face. He turned to us, spreading his arms as if in a blessing.

I tried not to be sick again. The side we hadn’t seen was a knot of scar tissue and collapsed bone. It glowed vermilion in the dying light. And he had no left eye.

I remembered that line of Rumi: The wound is the place where the Light enters you. And I thought, What bullshit. What utter bullshit. I could not begin to imagine what had happened to this man, and I wanted to sympathize with him—but he frightened me.

We pretended we were merely tired. I took off my scarf to blot my face dry. Luke brushed the dirt off the thin cloth of my skirt.

The one-eyed man watched him touch me. So did the women.

I thought, Maybe one of them is his wife. I tried smiling. If they called out a welcome, then I would feel okay. I would stop feeling self-conscious and scared and that other emotion that was creeping in. Foreboding. Shame — the old excuse for so much I’d done.

The women stared stone-faced at the sky. They were not welcoming us. I looked at Luke, pleading; the stranger looked at him too.

Luke pointed down a trail that hugged the hillside and the line of caves, and he asked slowly, “You … live … here?”

So that was where the man took us. I didn’t want to go; I lagged behind as Luke set off. Then the old man wrapped his hand around my wrist. He tugged. I wanted him to let go, but when I pulled away he pulled harder toward, and Luke was already well down the path.

I was glad to escape from the women, at least.

We marched past a series of small caves. The doorways were low and didn’t always have actual doors in them; smells of cooking and mildew and smoke lingered around the openings, and what we could see of the dark interiors was all furnished with stacks of crates and clothing hung up on poles. Luke fell behind, peering inside each one. When I tripped, it was the stranger who steadied me.

“So cool!” I heard Luke say. His voice echoed; he was speaking into somebody’s home.

I wanted to shout at him to hurry up. And shut up. But would that have helped?

Suddenly we were at the last cave, or at least the last we could see. It was isolated around a curve and its path had crumbled away. Even from the outside it reeked of urine.

The one-eyed man ducked inside. I ducked, too, just in time to avoid knocking my head hard on the rock as he pulled me after him.

In the past, our habits had taken Luke and me to some dirty squats and alleys, but none had made me as queasy as this. Maybe some of them should have, but back then I’d been just too far gone to know what to feel. You might think places like this would have nothing you want, but in our experience they were the only ones that did.

The cave was a home. Or at least it was a crash pad. It had a blanket on the floor, and a pillow, and a few plastic crates packed with clothes and bottles. The floor was all dirt. The ceiling was low.

My stomach lurched. The old man had swung me around and now stood between me and the door.

Now he spoke for the first time, in a voice that was low and rough and missing some tones. It came as a shock. I could not recognize a syllable and I had never been so afraid.

“Que voulez-vous?” I tried. “Was möchten Sie?” I mangled the phrase Turkish waiters said in cheap restaurants: “Ne istiyorsun? What do you want?”

I got the words out just as Luke slid in and stood next to me, bumping my shoulder in a gesture that was just friendly but I hoped would look protective.

In English, the old man said, “Mon-ey.”

In a way it was a relief.

“He thinks we’re rich,” I said to Luke. “He must have seen you in town today.” That might have been mean of me to say, but it was true; Luke could get careless when excited, and he did like to impress people.

What I did not say was that the stranger thought we were addicts. I did not need to say it. We could not have been the first people he’d lured up the hill, and we were addicts.

Right now I wanted nothing more than to sink into it again. My nerves stung with craving.

“Mon-ey!” the man repeated impatiently. He seemed to grow larger, filling the space between us and the cave mouth. He flicked his fingers in that Come here gesture. This time I thought it meant Pay up.

I dug into my skirt pocket. Luke let go of me to search his own pockets, but I’d have bet they held nothing but the red velvet box. I found a few coins and a bill worth one thousand lira. Maybe I could just hand that over and go. We wouldn’t take anything; we’d just pay.

The coins hit the ground. “Yok!” Our host had smacked my hand hard.

Then he reached into his own pants. He pulled out coins of his own and threw them at me. They bounced off my shoulders, my breasts, my arms. They slid down my clothes and my skin.

Oh, I thought. Oh.

I couldn’t speak, couldn’t look at Luke now, could only feel so full of longing that it made me retch. The one thing that would stop the retching was the thing I had vowed not to have.

“Yok!”

I had been digging in my pocket again, hoping to find it suddenly full. The one-eyed man grabbed my arm and shook hard. Then let me go, so he could make a circle with one thumb and forefinger. He plunged the other index finger inside.

At the height of our habit, I had been careless with my body and Luke did not mind. He encouraged it, in fact; he expected it. I had been lovable (he’d told me so even back then, in the worst of it) but my body did not matter. So I had been an easy trade for whatever was on offer.

Now things were different. Now we knew this: The body is not hidden from the soul, nor is the soul hidden from the body.

I felt in my bones that this was the moment. The moment at which we would have to become everything to each other, because Luke had to fight for me as he’d fought for his own life.

But he didn’t. He stood agape, staring at the coins in the dust.

A hand closed on my crotch. I felt it through the thin skirt, bruising me. The old man was faster than he seemed.

“Evet,” he said, “bu.”

Yes, this.

Almost the worst part was getting away. Tripping and sliding and battering myself against the cliffside, aching all over, and not just where I’d been grabbed, where the feel of a strange hand would linger long after I’d escaped. Vomiting into the dirt and my own hair, scattering the underfed cats. I tried to run past the women, who stared frankly through the smoke of their cigarettes; they knew exactly what had happened, or they thought they did.

Luke stumbled along a few feet behind me. He was the one who was crying. He called out to me that he was sorry and he hated himself, over and over, like a chant. What he needed was for me to say I forgave him and to take the blame, but I didn’t. I lurched away.

So I fell down the Hill of Dreams toward a purple, star-speckled sky, where Atatürk’s profile was lit up in red neon and held the most beautiful moon inside.

The Kemals brought me tea and some bumpy crackers. They brought warm wet towels and looked away as I washed the blood from my cuts. They did not ask questions, not even about Luke. He had vanished somewhere behind me; I suspected he was looking for a café that sold anisette raki or some other drink. He wasn’t choosy.

The Kemals brought a telephone.

“You call to your father,” they told me. “You call to your mother.”

They wanted me gone so badly.

I thought they must know the strange man. They could have told me who he was, how he lost his eye, how many other fools he’d led up to his cave. How many women he’d wrestled to the ground, how many times he’d succeeded. Mon-ey. It had extra meanings here.

I didn’t ask. I knew that no matter what I told them, they would think this was not the old man’s fault. In all other eyes, fault was ours, for being what we were. Maybe the Kemals had even steered us toward the caves, thinking I needed to stop a withdrawal. Maybe they had told the old man to go find us. No one seemed safe to me now.

I called Turkish Air and found out I could take a bus to Antalya that night and then a plane home. It would cost everything I had left, and in a way I was pleased. Now I would have all I deserved; I would have nothing.

While I was packing in the light of a dim one-bulbed lamp, Luke turned up at last. His face was flushed and he reeked of anisette. That much was inevitable.

But somewhere he’d discovered that he still had hope. He watched me stuffing my laundry into my backpack, and he tossed the red velvet box on top.

I tossed it back, but it fell inches short. I was still weak. “Take it,” I said. “Return it.”

He picked up the box and stood, wiping it off on his jeans. I noticed that they were torn at both knees. He held it out to me again, his heart, on his palm. “I got it for you.”

Because he implied I was lovable, because he had bought me a ring, he thought I would absolve him not just for today but for all the times we’d been in danger but too far gone to realize it. And he thought that if we came out of this engaged, we would truly be all right.

I would not take the box. I said, “You need the money.”

“I’ll throw it away.” He raised his fist as if to hurl it right then.

“That’s your decision.”

“I’ll spend it on — ”

“I don’t care.” I really didn’t. Except that I wanted him to spend it all and be ruined too. I wanted him to fail.

I said, “It is not my job to rescue you.”

Luke drew his hand back to throw the ring, probably at me. Neither one of us was lovable now.

Just then, the Kemals pushed the door open. They had heard our voices raised; they had seen the shadow of Luke’s fist through the plastic panel. “No, no,” they said. “Not the lady, not the miss. You go now.”

They meant both of us. Both of us should go. One of them took Luke outside and the other one carried my backpack to the bus stop.

My Kemal and I waited in silence until a bus came. I think he was the father. He hoisted my bag into the bus’s underbelly and we bowed to each other, curt and without touching. I climbed in, and the bus groaned, and I was on my way, past the riddled hills.

It had been a whirlwind. And I thought, Whatever we know will blow away: up to the sky, to the moon and stars. But it will not happen soon. Not soon enough to stop breaking our hearts.

The red profile on the Hill of Dreams grew smaller and smaller, till it was swallowed up in the sky and I didn’t care to watch anymore. And that was it; that was Göreme, that was Luke and me.

Featured image by Mehmet Turgut Kirkgoz on Unsplash

Cartoons: Happy Thanksgiving

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Herb Williams

November 24, 1951

Don Orehek

November 23, 1963

Kilgore

November 1, 1999

Veley

November 1, 1988

Foureyes

November 1, 1977

November 1, 1978

11-25-50

Roland Michaud

November 28, 1959

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

In a Word: A Tale of Two Turkeys

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

As you prepare to gather with family and friends next Thursday for Thanksgiving, we offer some pertinent questions (and answers) you can use to help avoid talking about politics over dinner: Why do a bird native to North America and a country in the Middle East have the same name? Are they related somehow? And which came first?

The short answer is yes, the words are related, but the story of their shared etymological history is a complex convolution involving international trade, exploration, and laziness.

Probably sometime during the 15th century, before Columbus set sail, Western Europe was introduced to what today we call the guinea hen, so named because it originated in Guinea on the west coast of Africa. There is some debate about exactly what route the guinea hen took to find its way into Western cuisine: did it come from Turkish traders in Constantinople, a commercial center of the then-growing Ottoman Empire; from Turkish traders on Madagascar; or from the Mamluk Turks of Ethiopia?

No one is entirely sure, but regardless of how the guinea hen entered Europe, it was known in English as the turkey-hen. At the time, the Ottoman Empire was also commonly called the Turkish Empire or just Turkey, and turkey had become a generic word — derived from a Medieval Latin phrase meaning “land of the Turks” — that was used to describe practically anything imported from the “exotic East” through Turkish merchants. Persian rugs, for instance, were called turkey rugs, and Indian flour was called turkey flour.

Fast-forward to the 1500s and the European exploration of the New World. Among the new wildlife these explorers and settlers found was a native bird that, with its fleshy, multicolored head and wrinkled wattle, resembled the turkey-hens they knew back home, though the American fowl were noticeably larger.

Those American turkeys were then brought back to Europe during the mid-16th century — some say by Spanish conquistadors, others by the Portuguese — and, because of their resemblance to the guinea fowl, were also called turkey-hens, or just turkeys. Over time, those American turkeys became the more popular poultry, especially in England, and the name turkey stuck with the bird in a way it didn’t with the guinea hen.

So, through an underdeveloped nomenclature system and a lack of scientific rigor, the bird’s name is ultimately derived from an adjective meant to describe exotic items traded from the East. That’s also where the modern country gets its name.

From the 16th through the 19th centuries, much of what we know today as the Middle East was part of the Ottoman Empire, which, as I said before, was also casually referred to as Turkey. Following the end of World War I in 1918, its capital, Constantinople, was occupied by Allied troops, and through various treaties and agreements, the lands of the once massive empire were repartitioned.

A group of Turkish nationalists, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, rose up in opposition to the repartition and fought what would be known as the Turkish War for Independence. In 1923, with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, a new country was officially recognized by members of the young League of Nations. Influenced by European usage, it was called Türkiye Cumhuriyeti — the Republic of Turkey.

Happy Thanksgiving to All!

Norman Rockwell

The Saturday Evening Post

March 6, 1943

People have always loved my grandfather’s painting, Freedom from Want, which first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post — it’s been celebrated and even lampooned many times. It is a painting about connection and the celebration of that connection.

No one is looking at the turkey or the grandmother and grandfather, and no one is praying or giving thanks — it’s what I call the “happy error” of the painting. Norman Rockwell was all about faces and interactions; if he painted everyone looking down and praying or looking back toward the grandparents and the turkey, you wouldn’t be able to see any of their faces.

Everyone is connecting with someone — the woman on the left is my grandmother Mary, who is conversing with the attractive woman across the table. The old woman is my great-grandmother, Pop’s mother, and she’s looking at Mary. The two men are interacting in the middle of the table (you just can’t see the one man’s face). The grandparents have a lovely, quiet, unspoken connection — the grandfather is clearly there to support her if the turkey gets too heavy. The man looking out at us is there to bring us into the moment, to invite us in.

The act of setting the turkey on the table brings movement into the painting. You can almost hear the lively exchanges at the table. And who is at the other end of the table? I can almost feel Pop’s presence there.

Enjoy your time with your family. In the end, that is what holidays are about. It’s not about getting the turkey with all its trimmings just right, its not about creating the perfect tablescape. It’s about family coming together to celebrate the simplest things — love and gratitude.

Warmest wishes,

Abigail

P.S. Pop always felt he had made the turkey too big. He also used to joke that the turkey was the only model he ever ate!

Kemal Pasha: Conflict in Turkey

If you’d like to read the original article as a PDF, download it here.

Related stories: “Turkey in Transition” by Isaac F. Marcosson, November 10, 1923, and “The Eastern Mess” by George Pattulo, December 23, 1922.

Kemal Pasha

October 20, 1923

by Isaac F. Marcosson

THERE was a time when Angora was famous solely for cats and goats. Today the shambling, time-worn town far up in the Anatolian hills has another, and world-wide significance. It is not only the capital of the reconstructed Turkish Government and the seat therefore of the most picturesque of all contemporary experiments in democracy, but is likewise the home of Ghazi Mustapha Kemal Pasha—to give him his full title—who is distinct among the few vital personalities revealed by the bitter backwash of the World War.

Only Lenin and Mussolini vie with him for the center of that narrowing stage of compelling leadership. Each of these three remarkable men has achieved a definite result in a manner all his own. Lenin imposed an autocracy through force and blood. Mussolini created a personal and political dictatorship in which he dramatized himself. Kemal not only led a beaten nation to victory and dictated terms to the one-time conqueror, but set up a new and unique system of administration.

Lenin and Mussolini have almost been done to death by human or, in the case of the soviet overlord, inhuman interest historians. Kemal Pasha is still invested with an element of mystery and aloofness largely begot of the physical inaccessibility of his position. To the average American, he is merely a Turkish name vaguely associated with some kind of military achievement. The British Dardanelles Expedition know it much better, for he frustrated the fruits of that immense heroism written in blood and agony on the shores of Gallipoli. The Greeks have an even costlier knowledge, because he was the organizer of the victory that literally drove them into the sea in one of the most complete debacles of modern times.

At Angora I talked with this man in a critical hour of the war-born Turkish Government. The Lausanne Conference was at the breaking point. War or peace still hung in the balance. Only the day before, Rauf Bey, the Prime Minister, had said to me: “If they [the Allies] want war they can have it.” The air was charged with tension and uncertainty. Over the troubled scene brooded the unrelenting presence of the chieftain I had traveled so far to see. Events, like the government itself, revolved about him.

In difficulty of approach and in the grim and dramatic quality of the setting, Anatolia was strongly reminiscent of my journey a year ago to the Southern Chinese front to see Sun Yat-sen. Between him and Kemal exists a certain similarity. Each is a sort of inspired leader. Each has his kindling ideal of a self-determination that is the by-product of fallen empire. Here the parallel ends. Kemal is the man of blood and iron—an orientalized Bismarck, as it were—dogged, ruthless, invincible; while Sun Yat-sen is the dreamer and visionary, eternal pawn of chance, and with as many political existences—and I might add, governments—as the proverbial cat has lives.

Turkey for the Turks

As with men, so with the peoples behind them. You have another striking contrast. While China flounders in well-nigh incredible political chaos, due to incessant conflict of selfish purpose and lack of leadership, Turkey has emerged as a homogeneous nation for the first time in its long and bloody history, with defined frontiers, a real homeland, and a nationalistic aim that may shape the destiny of the Mohammedan world, and incidentally affect American commercial aspirations in the Near East. “Turkey for the Turks” is the new slogan. The instrument and inspiration of the whole astonishing evolution—it is little less than a miracle when you realize that in 1919 Turkey was as prostrate as defeat and bankruptcy could bring her—has been Kemal Pasha.

He was the real objective of my trip to Turkey. Constantinople with its gleaming mosques and minarets, and still a queen among cities despite its dingy magnificence, had its lure, but from the hour of my arrival on the shores of the Golden Horn my interest was centered on Angora.

I had chosen a difficult time for the realization of this ambition. The Lausanne Conference was apparently mired, and the long-awaited peace seemed more distant than ever. A state of war still existed. The army of occupation gave the streets martial tone and color, while a vast Allied fleet rode at anchor in the Bosporus or boomed at target practice in the Sea of Marmora. The capital in the Anatolian hills had become even more inaccessible.

Every barrier based on suspicion, aloofness and general resentment of the foreigner—the usual Turkish trilogy— all tied up with endless red tape, worked overtime. It was a combination disastrous to swift American action. My subsequent experiences emphasized the truth of the well-known Kipling story which dealt with the fate of an energetic Yankee in the Orient whose epitaph read: “Here lies a fool who tried to hustle the East.”

To add to all this handicap begot of temperament and otherwise, the Turks had begun to realize, not without irritation, that the consummation of the Chester Concession was not so easy as it looked on paper. The last civilian who successfully applied for permission to go to Angora had been compelled to linger at Constantinople seven weeks before he got his vessica—as a visa is called in Turkish. Two or three others had departed for home in disgust after four weeks of watchful and fruitless waiting. The prospect was not promising.

When I paid my respects to Rear Admiral Mark L. Bristol, the American High Commissioner, on my first day in Constantinople, I invoked his aid in getting to Angora. He promptly gave me a letter of introduction to Dr. Adnan Bey, then the principal representative of Angora in Constantinople, through whom all permits had to pass.

I went to see him at the famous Sublime Porte, the Foreign Office and the scene of so much sinister Turkish history. Here the sordid tools of Abdul-Hamid, the Red Sultan, and others no less unscrupulous, lived their day. I expected to find the structure almost as imposing as its richer mate in history, the Mosque of St. Sophia. It proved to be a dirty, rambling, yellow building without the slightest semblance of architectural beauty, and strongly in need of disinfecting.

In Adnan Bey I found my first Turkish ally. Moreover, I discovered him to be a man of the world with a broad and generous outlook. An early aid of Kemal in the precarious days of the nationalist movement, he became the first vice president of the Angora Government. Moreover, he had another claim to fame, for he is the husband of the renowned Halide Hanum, the foremost woman reformer of Turkey, whom I was later to meet in interesting circumstances at Munich, and whose story will be disclosed in a subsequent article. Adnan Bey, however, is not what we would call a professional husband in America. Long before he rallied to the Kemalist cause he was widely known as one of the ablest physicians in Turkey.

He at once sent a telegram to Angora asking for my permission to go. This permission is concretely embodied in a pass—the aforesaid vessica—which is issued by the Constantinople prefect of police. Back in the days of the Great War it was a difficult procedure to get the so-called white pass which enabled the holder to go to the front. Compared with the coveted permission to visit Angora, that pass was about as inaccessible as a public handbill, as I was now to discover.

Adnan Bey told me that he would have an answer from Angora in about three days. I found that three days was like the Russian word seichas which technically means “immediately” but when employed in action or rather lack of action on its own ground, usually spells “next month.”

Red-Tape Entanglements

After a week passed, the American Embassy inquired of the Sublime Porte if they had heard about my application, but no word had come. A few days later Turkish officialdom went mad. An order was promulgated that no alien except of British, French or Italian nationality could enter or leave Constantinople without the consent of Angora. People who had left Paris or London, and they included various Americans, with existing credentials, were held up at the Turkish frontier, despite the fact that the order had been issued after they had started. Thanks to Admiral Bristol’s prompt and persistent endeavors, the frontier ban was lifted from Americans. Angora became swamped overnight with telegraphic protests and requests, and I felt that mine was completely lost in the new and growing shuffle.

Meanwhile I had acquired a fine upstanding young Turk, Reschad Bey by name, who spoke English, French and German fluently, as dragoman, which means courier and interpreter. No alien can go to Angora without such an aid, because, save in a few isolated spots, the only language spoken in Anatolia is Turkish. Reschad Bey was really an inheritance from Robert Imbrie, who had just retired after a year as American consul at Angora. Reschad Bey had been his interpreter. Much contact with Imbrie had acquainted him with American ways and he thoroughly sympathized with my impatience over the delay. He had a strong pull at Angora himself and sent some telegrams to friends in my behalf.

At the expiration of the second week Admiral Bristol made a personal appeal to Adnan Bey to expedite my permission, and a second strong telegram went from the Sublime Porte to Angora. Other Turkish and American individuals whom I had met added their requests by wire. Of course I was occupied with other work, but I had only a limited amount of time at my disposal and when all was said and done, Kemal was the principal prize of the trip and I was determined to land him. Early in July therefore I sent Reschad Bey to Angora to find out just what the situation was. He departed on the morning of the Fourth. When I returned to my hotel from attending the Independence Day celebration at the embassy I found a telegram from Angora addressed to Reschad Bey in my care from one of his friends in the government, saying that my permission to go to Angora had been wired nine days before! Yet on the previous morning the Sublime Porte had declared that Angora was still silent on my request.

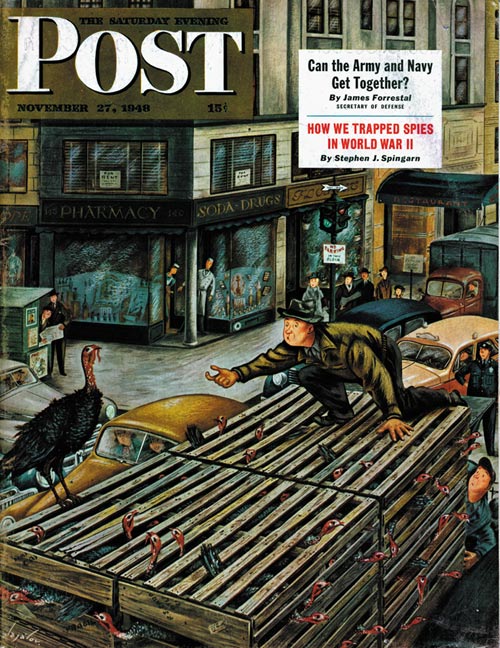

Classic Covers: How to Handle a Turkey

It isn’t just the farmers and poultry truck drivers who have a hard time handling turkeys. Sometimes the big birds were a handful for our cover artists and models. Why did one famous cover artist start “to feel like an assassin”?

Turkey Loose Atop Truck by Constantin Alajalov

Constantin Alajalov

November 27, 1948

“When I wanted to sketch turkeys as they look in a crate,” said cover artist Constantin Alajalov, “I found a wholesaler who sells a lot of them. For the turkey on the lam…he said, ‘Take your pick’. Every time I started to sketch a model, somebody bought it and bang, it was a dead bird. I began to feel like an assassin.” Our artist got the delightful Thanksgiving cover done, but said, “For Thanksgiving I may skip turkey…and have hamburger that I’m sure I don’t know, socially.”

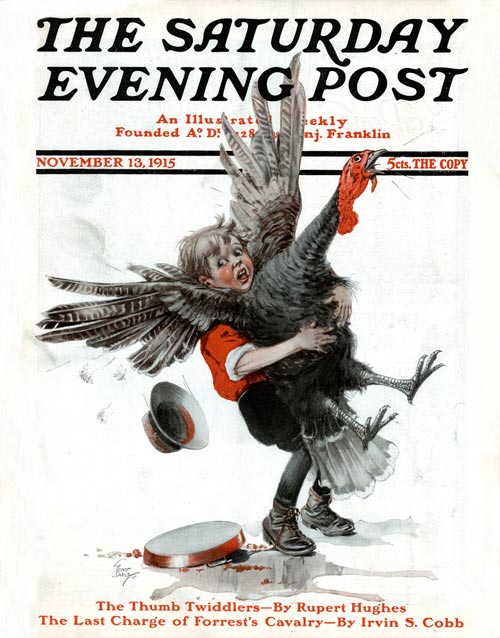

Squawking Turkey by Tony Sarg

Tony Sarg

November 13, 1915

This youngster managed to catch the turkey, but now what? The boy with arms full of squawking fowl is from 1915.

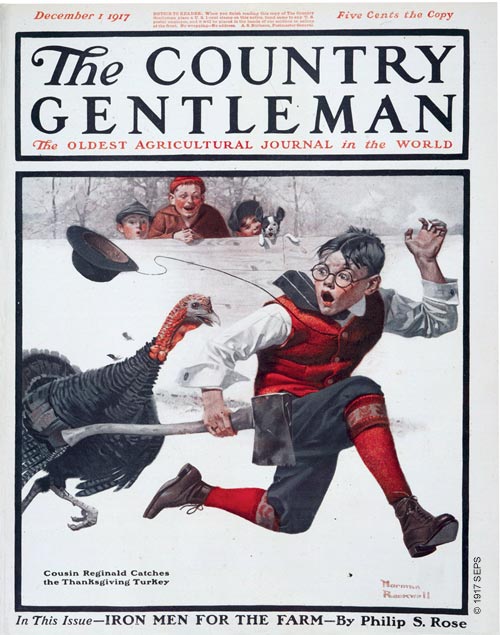

Cousin Reginald Catches the Thanksgiving Turkey by Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell

December 1, 1917

Norman Rockwell painted a lad he called Cousin Reginald, a city slicker. As we’ve shown you before, his mischief-loving country cousins often made a fool of Reginald. Now, we just know those rural boys told Reggie that catching the turkey would be a breeze. They are in the background being royally entertained.

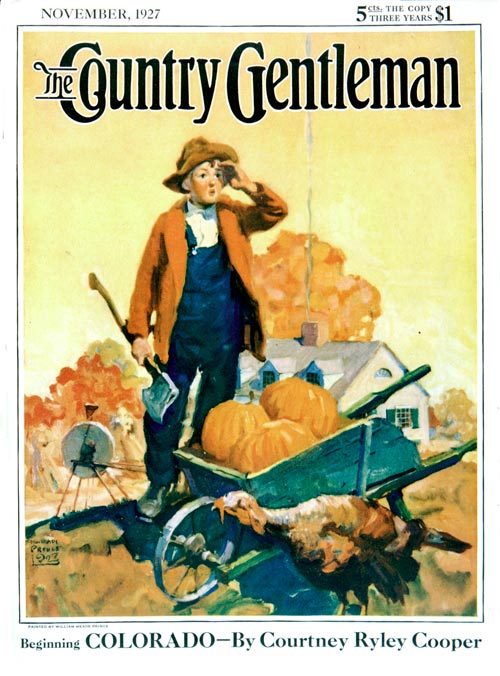

Where’s That Turkey? by Wm. Meade Prince

Wm. Meade Prince

November 1, 1927

This is no dumb Tom Turkey. When someone with an ax is looking for you, hiding is a good option. This colorful cover was painted for the Post’s sister publication, Country Gentleman by artist William Mead Prince.

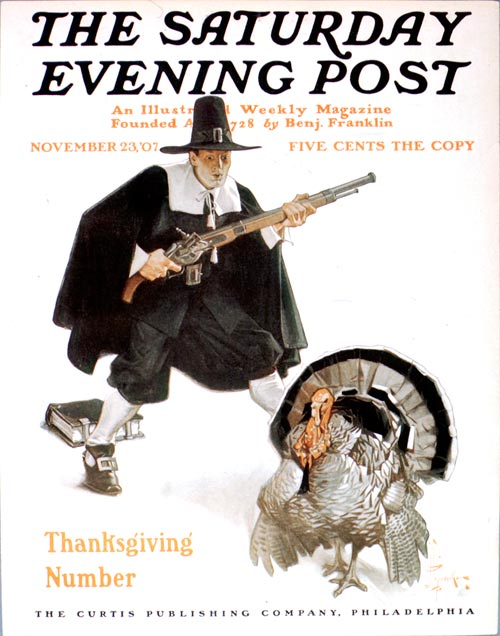

Pilgrim Stalking Tom Turkey by J.C. Leyendecker

J.C. Leyendecker

November 23, 1907

Would you believe this beautiful cover is from 1907? Artist J.C. Leyendecker did much more than paint ridiculously handsome men for Arrow Shirt ads. He did more Saturday Evening Post covers than any other artist. One of the earliest, and smartest, acts of George Horace Lorimer after taking charge of the Post was to hire J.C. Leyendecker to do a cover in 1899. Between then and 1943, Leyendecker did 322 Post covers, one more than Norman Rockwell. To honor his mentor, Rockwell chose to do one fewer cover.

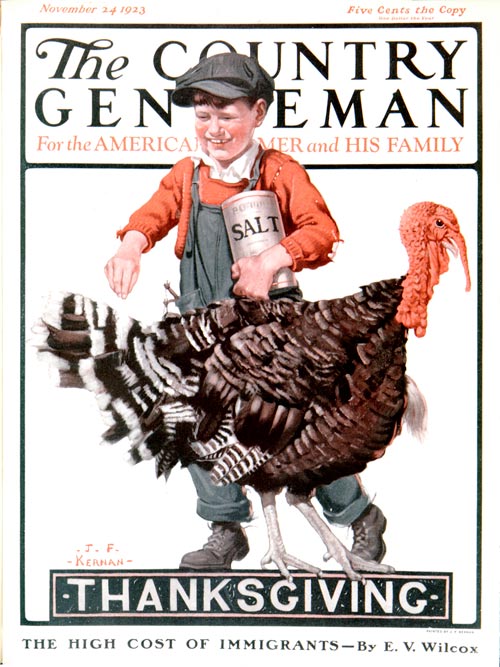

Thanksgiving by J.F. Kernan

J.F. Kernan

November 24. 1923

There’s an old myth that if you sprinkle salt on a turkey’s tail, you can catch it. Also, if you sprinkle pepper on a hen’s tail, she will lead you to her nest. These tricks may work, but only because if you’re close enough to sprinkle salt on a turkey’s tail, you’re close enough to catch it anyway and if you pepper a hen’s tail, she’ll probably get disgusted with you and stalk off….back to her nest.

Roast Turkey with Apples

Roast Turkey with Apples

(Makes 12 servings)

Brine:

- 1 1/2 cups kosher salt

- 1 1/4 cups brown sugar

- 10 whole cloves

- 3 teaspoons black peppercorns

- 2 quarts apple cider

- 4 quarts water

- Zest from 1 orange

- 3 teaspoons dried thyme

Make brine 1 day before roasting turkey. Combine all ingredients in nonreactive pot. Bring mixture to boil. Lower heat, simmer 15 to 20 minutes (partially covered).

Allow brine to cool completely.

Turkey:

- 3/4 cup apple cider

- 4 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons corn syrup, divided

- 1 (12 pound) free range turkey

- 2 tablespoons fresh thyme, chopped

- 1 tablespoon fresh rosemary, chopped

- 1 tablespoon fresh oregano, chopped

- 1 tablespoon fresh sage, chopped

- 2 teaspoons salt

- 1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- 1 tablespoon olive oil

- 4 large garlic cloves, sliced and divided

- 2 onions, quartered and divided

- 3 Golden Delicious apples, cored, quartered, and divided

- 1 teaspoon unsalted butter

- 3 cups gluten-free chicken stock, divided

- 1 tablespoon cornstarch

Remove giblets from turkey cavity. Set aside. Rinse turkey under cool running water, pat dry with paper towels. Pour brine in container large enough to hold turkey and small enough to fit in refrigerator. Immerse turkey in cooled brine; turkey should be completely submerged in liquid. Cover, refrigerate at least 8 to 10 hours, up to 24 hours.

Make turkey day of meal. Remove turkey from brine, rinse. Preheat oven to 375 F. combine 3/4 cup cider and 4 tablespoons corn syrup in small saucepan. Bring mixture to boil. Remove from heat, set aside. Lift wing tips up and over back; tuck under turkey. In medium bowl, combine herbs, salt and pepper. Rub turkey all over with olive oil, then rub herb mixture over skin and inside cavity. Place half garlic, onion quarters, and apple quarters into body cavity. Place turkey breast side up in shallow roasting pan. Arrange remaining garlic, onions, and apples around turkey in pan. Place turkey in oven, roast 45 minutes. Baste turkey with cornstarch-apple cider mixture, cover loosely with foil. Continue roasting 2 hours and 15 minutes more or until meat thermometer registers 180 F. Baste every 30 minutes with cornstarch-apple cider mixture.

While turkey bakes, melt butter in medium saucepan over medium-high heat. Add reserved giblets and neck; sauté 2 minutes each side or until browned. Add 2 cups chicken stock, bring to boil. Cover, reduce heat. Simmer 45 minutes. Strain mixture through fine sieve into bowl, discarding solids. Reserve 1/4 cup broth mixture.

Remove turkey from oven, let stand 10 minutes. Remove from pan, reserving drippings for sauce. Place turkey on platter and keep warm.

Spoon off any excess fat from drippings in roasting pan. Spoon out solids from pan, place in fine sieve set over bowl, pressing on solids to release any excess juice. Place roasting pan over 2 burners over medium-high heat. Add 1 cup chicken stock, cook (scraping up browned bits on bottom of pan.) Strain drippings through sieve into medium saucepan. Add juices from solids and giblet broth mixture to pan, cook over medium heat. Combine reserved 1/4 cup giblet broth with cornstarch; whisk into saucepan. Add 2 teaspoons corn syrup, stirring with whisk. Bring to boil; reduce heat and simmer until thickened. Carve turkey and serve with gravy.

Recipe from Glutenfreeda Online Magazine and Recipe Book.