Vampire Soap Opera Dark Shadows Crept into Film 50 Years Ago

It’s unusual, but not unheard of, for a TV series to break out into theaters as the regular show continues to run on television. It’s slightly more common with animation (or puppetry), with examples like The Simpsons, South Park, and The Muppet Show all pulling it off during their runs. In terms of live-action, the list is much smaller, with notable efforts being the 1960s Batman and The X-Files, which scored a hit film between seasons five and six of the series. However, Dark Shadows managed to put a feature film on the big screen featuring a number of main cast members while the series continued to run daily. It wasn’t a surprise that the show bucked tradition or expectations; after all, it had been doing just that since its 1966 debut.

Dark Shadows was the brainchild of Dan Curtis, a writer, director, and producer whose output had a seismic impact on the horror television genre. Over the years, Curtis hopped back and forth between television and film. His 1975 TV movie Trilogy of Terror, based on three stories by Richard Matheson, is routinely listed among the best horror films ever made for the medium. He adapted a number of classic horror novels for TV to great success, including the 1973 version of Dracula with Jack Palance in the lead. In the 1980s, he adapted Herman Wouk’s World War II novels The Winds of War and War and Remembrance into a pair of mini-series that were nominated for a combined 19 Emmy Awards, Remembrance winning for Best Mini-Series. He also directed The Night Stalker, the film that introduced Jeff Rice’s intrepid reporter character Carl Kolchak to wider audiences; the 1972 TV film was the highest rated TV film of all time at that point, with 48 percent of all TV viewers in the U.S. tuned into the movie on the night it ran. That film led to a hit sequel, The Night Strangler, and the spin-off series, Kolchak: The Night Stalker.

Curtis formed the idea of Dark Shadows around a dream he had of a woman on a train. Encouraged by his wife, his successfully pitched his concept of a Gothic soap opera to ABC in 1965. He teamed up with Art Wallace, a seasoned writer with years of genre TV experience, to flesh out the overall idea and story bible for the new series. Wallace and Curtis wrote the first eight weeks of the series (40 episodes), and then Wallace traded back and forth with screenwriter and playwright Francis Swann on the next nine weeks.

The series began by leaning on the more traditional tropes of Gothic romance, with Curtis’s “woman on the train” becoming Victoria Winters, who was drawn into a Jane Eyre-inspired plotline. Less than a year into the run of the show, ratings were less than great. In an effort to boost interest, Curtis went all-in on the horror angle by introducing vampire Barnabas Collins, played by Jonathan Frid. The show exploded in popularity, picking up three million viewers in a year. The daily timeslot (usually 4 p.m., though it had runs at 3:30 p.m.) gave teens the chance to discover the show after school, and they became a solid component of the audience. Emboldened by their success with Barnabas, the creators went full steam ahead with ghosts, witches, werewolves, and more. Time-travel became a component, with entire weeks of the series spent in different time periods; of course, Barnabas (as a vampire) and others could appear up and down the timeline, while some actors simply played their ancestors or descendants as needed.

A scene from House of Dark Shadows (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros. Entertainment)

With the show, and Barnabas in particular, taking off, Curtis started pitching for a theatrical film spin-off and sold MGM on the idea. One early concept had the creative team re-editing series episodes into a film, but that was abandoned in favor of doing a tight, film-length version of Barnabas’s main story. Curtis and the writers and producers of the daily show coordinated to write out the necessary members of the main cast for when they would needed during the six-week film shoot. Some of the same sets and locations were used. However, the film milieu obviously provided greater leverage for violence and scares, allowing for things that were out on TV (like dripping blood from vampire fang-induced neck wounds) to be shown. The film was released on August 25, 1970, and while it wasn’t a runaway success, it did double its budget, allowing MGM to greenlight a second film.

The Night of Dark Shadows trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros. Entertainment)

Unfortunately, the ratings for the daily show started to taper off. After a high of seven to nine million viewers a day in mid-to-late 1969, viewership went into a skid. There are a number of theories for this, running from the 1970 recession forcing budget cuts, to the loss of ratings leading to local stations dropping the show and feeding a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure. Whatever the final reason, Dark Shadows aired its last episode on April 2, 1971. A few months later, the second film, Night of Dark Shadows, hit theaters. This time, due to the unavailability of Jonathan Frid, who had gone on to other projects after the cancellation of the series, the movie focused on Barnabas Collins’s descendant Quentin and the witch Angelique. At the last minute, MGM forced Curtis to cut more than 35 minutes from the film to get its run-time down; all involved felt this hurt the film in a number of ways. When the movie opened, it made back its budget, but that was it for the original TV and film incarnations of Dark Shadows.

Over the years, the show has been subject to a number of reboot attempts. NBC put a new version on the air in early 1991, starring Ben Cross as Barnabas. Initial ratings were huge, but the show was quickly derailed by pre-emptions brought on by ongoing coverage of the Gulf War. The show was cancelled after a single season. A pilot was made for the WB in 2004, but didn’t get a series order. Tim Burton directed a new big-screen version in 2012, which starred his frequent collaborator Johnny Depp as Barnabas Collins; although the film made money, it was something of an overall miss. Jonathan Frid put in a cameo for the film, which was his last screen appearance before he passed away that year. Since the fall of 2019, Warner Bros. Television and The CW have been developing a sequel to the original series, tentatively titled Dark Shadows: Reincarnation. Dan Curtis passed in 2006, but his daughters Tracy and Cathy hold the rights to the series and are involved in the production of the potential new version.

The work of Dan Curtis in general and Dark Shadows in particular continues to resonate across media. The X-Files creator Chris Carter spoken often of the debt his show owed to Kolchak. You can see its echoes in Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, among others, and in the number of daytime soaps that adopted supernatural plotlines, including Days of Our Lives and the almost entirely supernatural General Hospital spin-off, Port Charles. Perhaps a new version will jump up and seize the zeitgeist again; maybe it will even be popular enough to produce new films while the new series runs. If Dark Shadows has taught us anything, it’s that nothing stays dead for long.

Featured image: Ironika / Shutterstock

We Are Lovecraft’s Country

Howard Phillips Lovecraft remains, 130 years after his birth and 83 years after his death, a study in contradictions. Mostly unknown during his lifetime, the reputation of his work has grown in the years after to the point where the adjective “Lovecraftian” is universally used to describe otherworldly or “cosmic” horror. He insisted on the use of proper English grammar and pushed to raise the bar for supernatural fiction while publishing primarily in the pulp magazines that were frequently reviled by critics. His view of horror and science fiction expanded the minds and possibilities of the writers he influenced, and yet he himself held intensely bigoted, racist, and misogynistic views. He supported and encouraged a wide circle of writers, but criticized others if they wrote for mainstream publications like, ahem, The Saturday Evening Post. And now, at possibly the height of his literary and cultural influence, Lovecraft is back in the public eye thanks to the new HBO series, Lovecraft Country. Based on the superlative novel by Matt Ruff, the series reckons with Lovecraft’s legacy of intolerance through the lens of a Black cast in the 1950s. One episode in, the series is already inspiring debate, discussion, and myriads of internet think pieces on the racism of Lovecraft. Of course, and possibly unsurprisingly, as is always the case with the best horror, some of the most unsettling themes and images are directly applicable to today’s America.

Although he’s a towering figure in fantasy, horror, and science fiction literary circles, he’s still a sort of peripheral figure to the mainstream. His most famous creation is the tentacle-faced Cthulhu, a monster that has had an increasing presence in popular culture in the past few decades, popping up everywhere from T-shirts to Metallica songs and surprise appearances in films like last year’s Underwater. His work has influenced the likes of Stephen King, Guillermo Del Toro, Neil Gaiman, John Carpenter, Alan Moore, Hellboy creator Mike Mignola, and many more. During his lifetime, he corresponded with writers who became important figures unto themselves, like Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian, Psycho writer Robert Bloch, and August Derleth, founder of the publisher Arkham House (and yes, that’s where the Arkham Asylum of Batman fame got its name).

And so, his influence persists, and therein lies the heart of the problem. Lovecraft isn’t just problematic; his work and essays and his more than 100,000 letters have incontrovertible evidence that he was xenophobic, with negative opinions about people of other colors, countries, and religions. He compared Black people to “beasts,” decried the “mongrelization” of the human race, and wrote a 1912 poem called “On the Creation of N——.” He even owned a cat named, somewhat unbelievably, “N—– Man.” He is perhaps the ultimate avatar of the notion of trying to separate the artist from the art. The majority of today’s talents who look at Lovecraft as an influence readily decry his deeply rooted racism, and note that it’s his broad mythology of gods and monsters that remains the draw.

The official trailer for Lovecraft Country. (Uploaded to YouTube by HBO)

That’s one of the things that’s so potent about Lovecraft Country as both a book and a series. By placing Black characters at the center of the narrative, it’s a refutation of Lovecraft’s views even as it honors his place in the supernatural canon. Then, by taking the extra step and using the Jim Crow-era 1950s, with its deeply-rooted prejudices and unnerving historical details like “sundown towns,” it adds an extra dimension, a real-world dread that overlies the indescribable monsters of Lovecraft’s prose. The most frightening scene in the first episode isn’t the climactic monster attack in the woods; it’s the scene of the three protagonists trying to drive out of the county before sundown as they’re tailed by a racist sheriff who is keeping a very close eye on the speed limit. We may not be able to conceive of Elder Gods from the outer darkness, but the reality of that scene is, especially in light of recent events, all too real.

The phrase “Lovecraft Country” is rooted in literary analysis of his works. A Rhode Islander, Lovecraft set his tales in New England. It may be the area of the Ivy League (and Lovecraft’s own fictional Miskatonic University), but it also contains stretches that are pastoral and parochial. The descriptor is meant to evoke the rolling hills dotted with small towns and country regions that could, behind the veneer of daylight, hide existential dread. Certainly, Ruff’s use of the title for his novel was meant to evoke that dissonance.

The first episode of Lovecraft Country, “Sundown.” (Uploaded to YouTube by HBO)

But the issue also goes beyond that. It’s much harder to separate the artist from the art if you belong to a group that he maligned. If one exists in a kind of bubble of privilege, one might only see the veneer of daylight, and not the darkness that others have to contend with on a daily basis. Lovecraft Country consciously dives in the great contradiction of Lovecraft, acknowledging his work as an elder statesman of the genre while likewise address his deep flaws, flaws that continue to bedevil the United States a century later.

Horror fiction usually arrives right when it’s supposed to, reflecting a society’s fears and demons at the time when the work was created. Lovecraft Country manages to address hundreds of years of horror and decades of division while also being entertaining. Which brings us again to the great contradiction of H.P. Lovecraft: while his own life and work bear the stain of the kind of irrational hate that he harbored, its existence and influence allow others to present some harsh lessons and explore some equally harsh truths. For better or worse, America is Lovecraft’s Country, but he’s gone; horror story or happiness, the ending is up to us.

Featured image: Lovecraft collections published by Del Rey. (Photo by Troy Brownfield. Cover art and book editions ©Del Rey Books)

Wit’s End: Everything I Needed to Know, I Learned from Cheers

This month, my children will start the school year at home. Instead of full days of 8th and 6th grade, they will have Zoom class for three hours in the morning.

If they were in the lower grades, I would be worried. But they’re strong readers, so the key battle has already been won. My favorite book in 7th grade was a 1,200-page family saga set in Wales and based on the Plantagenet family of Edward III. The Wheel of Fortune by Susan Howatch left an indelible mark on me as I absorbed its many lessons. What they taught in 7th grade history — a class called, for maximum drabness, “social studies” — I forget.

When not poring over the extramarital affairs of the Plantagenets, I watched TV, and that was where the real learning happened. The sitcom Cheers ran on NBC from 1982 to 1993, and my siblings and I watched every episode with rapt attention. The show’s creators, brothers Glen and Les Charles, seemed to me figures of immense national importance, our era’s Orville and Wilbur Wright.

Cheers was set in a Boston bar, owned by a guy whose drinking problem had destroyed his career as a professional baseball player. At age ten, this setup gave me a lot to chew on. But there was more: He carried on a flirtation with a blonde waitress, a former grad student whose book smarts were of little help in a pub setting. The shrewdest person on the show was the bar’s other waitress: a perennially angry single mom who started with four kids and proceeded to have four more with her ex-husband.

This was unlike anything in our real lives. We lived 2,000 miles from Boston in a small town surrounded by peanut fields. None of us had ever set foot inside a bar. The local watering hole was called Goober McCool’s — a place where, when I grew up, no one knew my name because it was not my scene.

So watching Cheers made us kids feel cosmopolitan and savvy. In short order, we learned that the Red Sox were a Boston baseball team and that, under the influence of alcohol, adults made foolish choices they came to regret. Meanwhile, our teachers were quizzing us on Eli Whitney. Pfft, who cared? Why study the cotton gin when you could watch Carla Tortelli slinging gin while saying:

“It was a magical moment. You know, it was like I was transported back in time. I wasn’t a tired old woman with six kids. I was a fresh young teenager with two kids.”

In fact, the wisest people on Cheers were often the ones who’d spent little time in school. A white-haired simpleton served as a sort of Zen master while polishing glasses behind the bar. (“Coach, I’m having blackouts!” “Kind of a nice break in the day, isn’t it, Sam?”)

Characters who lectured others from a position of superior knowledge were usually wrong. The clearest example was a mailman named Cliff who said things like: “It’s a little-known fact that cows were domesticated in Mesopotamia and were also used in China as guard animals for the Forbidden City.”

In fact, the Charles brothers, both of whom graduated from a small college near Los Angeles, seemed a bit jaded about people who spent half their lives in school. Their college-educated characters — writer Diane, psychiatrists Frazier and Lilith, and businesswoman Rebecca — had countless humbling interactions with the wait staff.

But the bar’s professional types were not above dishing it out, either. Lilith once described Carla as “a woman whose hair has never seen a greasy pot it couldn’t scrub clean.”

And, when introduced to Carla’s hockey player ex-husband, Frazier quipped: “Have we met? You wouldn’t, by any chance, be the bogus missing link exhibited at the Amsterdam World’s Fair?”

In the midst of this ongoing class warfare were simple drunks like Norm. One of the more wholesome role models on the show, he was an accountant who had no interests in life but drinking beer.

“Whatcha up to, Norm?” someone would say.

“My ideal weight if I were eleven feet tall.”

“What’s the story, Norm? “

“Boy meets beer. Boy drinks beer. Boy meets another beer.”

Norm advanced another of the show’s main themes: the battle of the sexes. He was always hiding out from his dreaded wife, Vera. Like Norm’s marriage, most Cheers romances were ambivalent, volatile, and steeped in mutual distrust. Here’s Sam describing his on-again, off-again relationship with Diane:

“You gotta get past this early infatuation and get to the point where you’re sick and tired of each other; then you’re ready for marriage. Look at Diane and me, we waited five years to get married. If it were up to me, we’d wait another five.”

“I thought you were seeing someone,” Diane once said to Carla, who unerringly took up with the wrong men.

“His fingerprints grew back. He had to leave the country.”

Still, the Cheers crowd clearly enjoyed, even sought out, each other’s company. Despite the characters’ differences, the bar’s overall mood was tolerant and gracious, as if the barflies sensed their troubles were all the same.

I didn’t learn algebra from Cheers, but over the years I acquired a working knowledge of how to be American. The ideal citizen was basically good-natured, willing to live and let live because one person’s foible was another one’s punchline and so contributed to the general hilarity. And everyone could drink to that.

Now, stuck at home, my daughter watches a lot of Parks and Recreation, a sitcom that ran from 2009 to 2017. Here’s the show’s most loveable character, Andy, who shines shoes for a living:

“I once forgot to brush my teeth for 5 weeks. I didn’t actually sell my car, I just forgot where I parked it. I don’t know who Al Gore is and at this point I’m too afraid to ask. When they say 2 percent milk I don’t know what the other 98 percent is. When I was a baby, my head was so big scientists did experiments on me. I once threw beer at a swan and then it attacked my niece, Rebecca.”

I’d say the ’20-’21 school year is very much in session.

Featured image: haymickey (pixabay)

What’s Bugging Andy Griffith?

Originally published January 24, 1964

Griffith is a fearsome worrier, so petrified by social situations that he avoids most big Hollywood functions. “I feel I just might not be able to cope,” says Griffith. “I wish I could be like [Sheriff] Andy Taylor. He’s nicer than I am — more outgoing and easygoing. I get awful mad awful easy.” Griffith freely admits to what seem to him monumental shortcomings, among them a tendency to keep public emotion at arm’s length. “It’s the way we mountain people are,” he tries to explain.

“My own grandpappy never showed big emotion but once in his life. Lying on his deathbed, he suddenly got up and kissed my grandma gently on the check — he’d never been seen before even to touch her! Then he took back to his bed and died. One emotional act in his whole life, but no one ever forgot it.”

When Andy looks back on his childhood, he sometimes assumes a prismatic double vision. One moment he recalls “the fun we kids had in the summer kickin’ rocks and lyin’ to each other in that wonderful slowed-down time between dusk and dark.” In the next, he speaks of himself as a skinny, gawky, rejected, unathletic kid hurt by his nickname of “Andy Gump” [a cartoon character] and remembers that once, when he was 11, someone called him “white trash.”

As he expands as a man and an actor, Griffith thrives in what another rural comic, Pat Buttram, has called the best of all possible worlds — “a Southern accent with a Northern income.”

Once, aboard an airliner, Griffith turned to his manager. “Say, you think I oughta lose my Southern accent?” he asked seriously.

“Sure,” the other shot back, “if you want to try another line of work.”

—“I Think I’m Gaining on Myself” by Donald Freeman, January 25, 1964

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: PictureLux / The Hollywood Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

How Hopalong Cassidy Brought the Western to Television

It’s not unusual for a character from novels and short stories to make the jump to film or television. In fact, so-called transmedia properties are extremely common today, with comics designed to be films or TV shows that get adapted into long-running series of books. However, it’s not every day that a character crosses over, and brings an entire genre with them. That was the case on June 24, 1949, when Hopalong Cassidy made the jump from books and movies to the small screen, kicking off the legacy of the Western on television.

Hopalong wasn’t new in 1949. The character first appeared in the writings of Clarence E. Mulford. He created the character in 1904, and the first book to feature Hopalong, Bar-20, saw publication in 1906. The original version of Hopalong was considerably more of a rude character than he would be onscreen; he also owed his nickname to a wooden leg. By the time that he became the title character of 1910’s Hopalong Cassidy, the cowboy already had a strong following.

Some of Cassidy’s rougher edges where smoothed when he made the transition to the big screen in 1935. Actor William Boyd took on the role, and the character became a bastion of fair play. Perhaps as a nod to his more dangerous literary persona, Cassidy (who earned his nickname from a gunshot-induced limp rather that a wooden leg) wore all black, including his hat, a departure when most good guys were clad in light colors and white hats. The first film, Hop-Along Cassidy (the inexplicable hyphen was dropped later), took elements from the books but wasn’t a slavish adaptation. Boyd would play Cassidy an astonishing 66 times between 1935 and 1948, with ten different sidekicks accompanying him throughout the films.

Producer Harry Sherman had grown tired of the films by 1944. Boyd took the unusually step of buying the right to the character from Mulford and the previously produced films from Sherman. By 1948, Boyd had a new idea. He took the films to NBC for broadcast; 52 of the movies were edited down to episode length for a Hopalong Cassidy TV series. The first episode, “Sunset Trail,” ran on June 24, 1949.

The young medium proved to be a perfect fit for Boyd and his character. Cassidy’s popularity went through the roof, with the show beloved by kids and adults alike. The remaining 12 films were edited for a second season, and Boyd put together a company to make new episodes (which also featured Edgar Buchanan as new sidekick Red Connors). The edited movies comprised the first two seasons, and the 40 new shows completed two more seasons through 1955. During that same period, Boyd starred in a radio drama version of the show that ran for 105 installments. With the films, TV, and radio (as well as an ongoing comic strip) behind him, Boyd became a massive celebrity, covered by magazines and touring the world.

When he finally retired in his sixties after 20 years of playing the character, Boyd’s primary reluctance at saying good-bye to the show was the employment of his production team and crew. By a stroke of luck, CBS was putting together the TV adaptation of another popular Western radio program. Boyd kept his crew employed by putting them to work at CBS on the new show. It was called Gunsmoke, and it would run for 20 years.

Hopalong Cassidy presaged the dominance that Westerns would display at both the movies and on television throughout the 1950s. While many of the early shows, like Cassidy, were child-friendly, Gunsmoke and its immediate prime-time antecedent, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, were directed at more adult audiences. Those programs led a Western expansion that saw more than 30 of the shows on the air by the end of the decade, with eight of the top ten shows in March of 1959 being Westerns. In the theaters, approximately 700 Westerns were released between 1950 and 1959.

Critics and scholars continue to debate what caused the decline of the Western. While the form was still popular in the 1960s, it wasn’t as pervasive. Pressure groups decried the violence present in some Westerns, while others were affected by general fatigue with the genre. The Space Race kicked off an interest in science fiction programming that, coupled with the rise of color TV, saw “space shows” replace “horse shows.” There was also a shift in the 1960s to programs set in both urban settings and contemporary times, both of which left the Western behind.

The Western itself has never completely left television, and it likely never will. Today, programs like Kevin Costner’s Yellowstone still run on outlets like the Paramount Network, while the general influence of the Western is seen in a variety of diverse 2000s shows like Justified, Hell on Wheels, and the genre-bending science-fiction of Westworld. The general appeal of the genre has never been in question; it relies on the idea of open ranges, the possibility of a bright future, and the notion that the proper person riding in on a good horse can make things right. The dream of the West might be a dream, but at least it’s a good one.

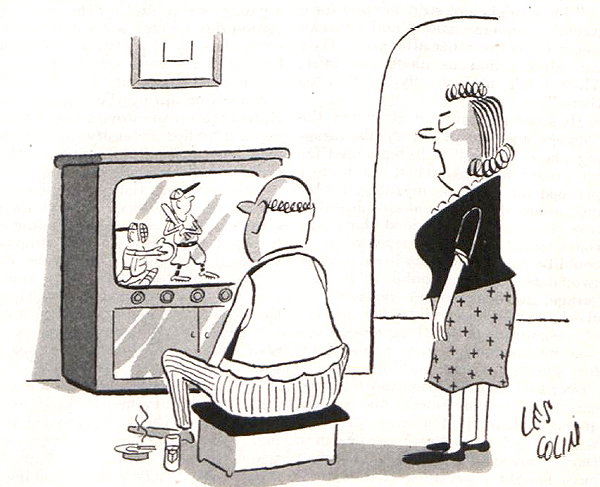

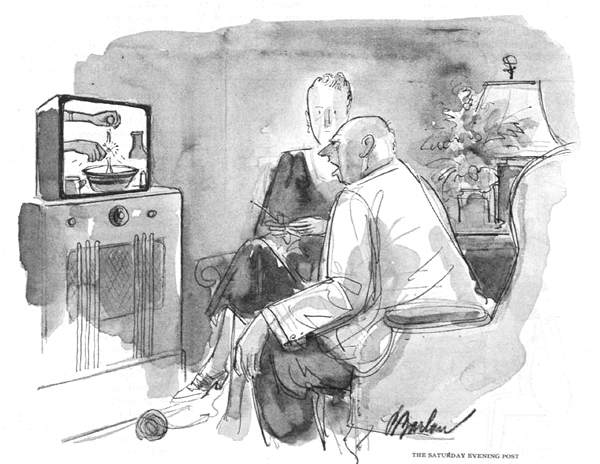

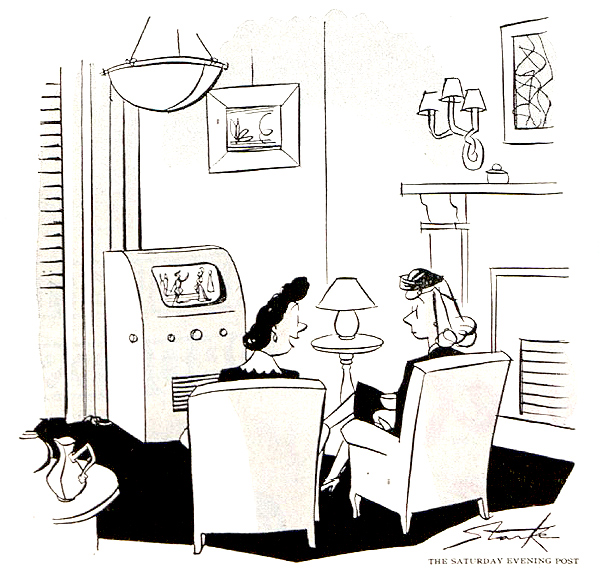

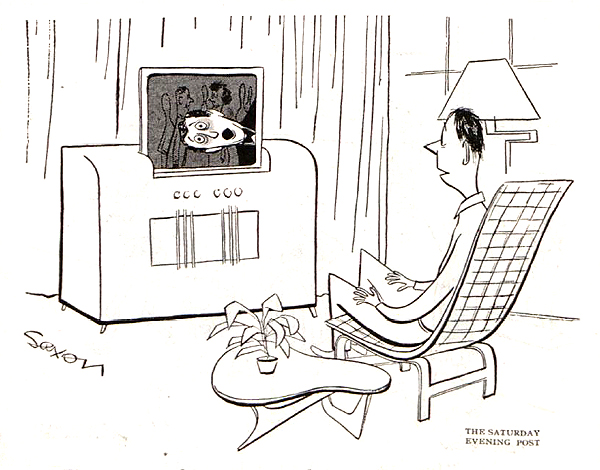

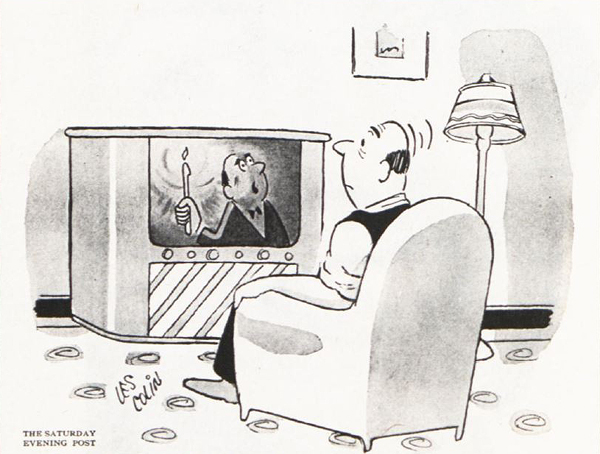

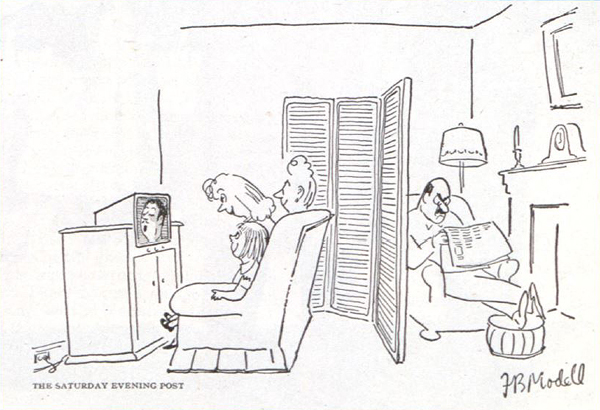

Cartoons: Mid-Century Television Troubles

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Les Colin

February 16, 1952

February 12, 1949

Starke

February 7, 1948

Saxon

November 16, 1946

Les Colin

August 28, 1948

March 13, 1948

The 50 Greatest TV Theme Songs of All Time: Live-Action

For Part 2, read The 25 Greatest TV Theme Songs of All Time: Spoken-Word.

For Part 3, read The 40 Greatest Animated TV Series Theme Songs

How do you determine the greatest TV show theme songs of all time? It’s a daunting task. Consider that, in 2016, more than 1,400 shows ran on prime-time television in the United States — that doesn’t include streaming — and most of those shows had some kind of opening sequence with music. Tom Morello of the band Rage Against the Machine suggested that bands should be considered for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on the basis of “impact, influence, and awesomeness”; we’ll use a similar criteria of catchiness, memorability, and appropriateness to rank TV theme songs. We’ll also be breaking this list into three distinct categories: live-action, animated, and spoken-word/voiceover themes. We begin with Part 1: Theme songs for live-action shows.

50. Veronica Mars

2004-2007, 2014, 2019; “We Used to Be Friends” by The Dandy Warhols

Uploaded to YouTube by Veronica Mars

This 2003 Dandy Warhols track was both bracingly of-the-moment and completely appropriate for the Kristen Bell-led teen detective show. Veronica Mars ran three seasons, had a film continuation released in 2014, and will return for a multi-episode run on Hulu this year.

49. Friends

1994-2004; “I’ll Be There for You” by The Rembrandts

Uploaded to YouTube by alliemaster93

We’re practically legally obligated to include this one. The Rembrandts co-wrote the original minute-long version of the tune with Friends producers David Crane and Marta Kauffman, Kaufman’s husband Michael Skloff, and musician Allee Willis. The song became so popular, with DJs playing it on the radio, that the group recorded an extended version for a single, and a companion video was produced featuring the six leads of the show. The release was a massive hit around the world between 1995 and 1997, and notched No. 1 positions on the U.S. Mainstream, Adult Contemporary, and Airplay charts.

48. Tie: Perry Mason and Ironside

Perry Mason: 1957-1966 by Fred Steiner

Uploaded to YouTube by spudtv

Ironside: 1967-1975 by Quincy Jones

Uploaded to YouTube by TeeVees Greatest

Raymond Burr headlined two much-loved dramas with highly regarded theme songs. Legal drama Perry Mason’s theme had a jazzy swagger that befitted the character borne from Erle Stanley Gardner’s detective stories (some of which ran in The Saturday Evening Post). Ironside featured Burr’s wheelchair-bound crime solver and a theme by the legendary composer and producer Quincy Jones. It was the first TV theme to have its sound rooted in synthesizer.

47. Firefly

2002-2003; “The Ballad of Serenity” by Joss Whedon

Uploaded to YouTube by Mikey Mo

The first Joss Whedon show on the list, the space western Firefly boasted a theme composed by the writer himself. It was performed by Sonny Rhodes, and remarkably infused the space theme into a traditional country tune.

46. Buffy the Vampire Slayer

1997-2003; by Nerf Herder

Uploaded to YouTube by Krasus

Joss Whedon gets a lot of credit for revitalizing genre TV. His first hit, based on the film that he wrote, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, came packed with a great theme. It starts with a nod to the old Universal horror days with a fugue on organ. Then it rips into four-on-the-floor post-punk surf-rock, turning the old themes on their heads in the same way that the show stretched horror tropes.

45. The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr.

1993-1994; by Randy Edelman

Uploaded to YouTube by 6201Films

This weird western starring Bruce Campbell ran for only 27 episodes in the mid-1990s. However, it earned a cult following and is fondly remembered by TV critics. Incredibly, the theme lives on, having been appropriated by NBC for its Olympics coverage since 1996.

44. Gilligan’s Island

1964-1967; “The Ballad of Gilligan’s Island” by George Wyle and Sherwood Schwartz

Uploaded to YouTube by 4458RobertC

In one of the theme songs that actually states the show’s premise, “The Ballad” explains how the S.S. Minnow got lost in a storm with seven very different people aboard. The words and music were by George Wyle and show creator Sherwood Schwartz.

43. The Fall Guy

1981-1986; “The Unknown Stuntman” by Dave Somerville

Uploaded to YouTube by oneforperry

Producer Glen A. Larson wanted to develop a show featuring a stunt man. Coincidentally, his friend (and frontman of The Diamonds) Dave Somerville had written a song about a stunt man for a show that never went forward. Inspired by the song, Larson created the character of Colt Seavers, a stunt man and bounty hunter. Lee Majors, having worked with Larson on The Six Million Dollar Man, signed on to play Seavers and even sang the theme song. The “I’ve been seen with Farrah” line was a reference to Majors’ then-marriage to Farrah Fawcett of Charlie’s Angels; she also appeared in The Fall Guy pilot.

42. Dallas

1978-1991, revived 2012-2014; by Jerrold Immel

Uploaded to YouTube by TeeVees Greatest

Jerrold Immel broke into television composing scores for Gunsmoke in the early 1970s. He would go on to write the theme for Dallas and score 55 episodes of the show. He also created themes for other shows like Dallas spin-off Knots Landing and the third season of Walker, Texas Ranger. The Dallas theme, an improbable blend of western film tropes and disco, remains instantly recognizable.

41. The Munsters

1964-1966; by Jack Marshall

Uploaded to YouTube by POP COLORTURE

The surf-inspired theme for monster comedy The Munsters received a Grammy nomination in 1965. Some readers might recognize the song from Fall Out Boy’s 2015 song “Uma Thurman,” which used the theme as the source for its primary sample.

40. WKRP in Cincinnati

1978-1982, 1991-1993; by Tom Wells and Hugh Wilson with Steve Carlisle vocals

Uploaded to YouTube by Classic Sitcoms

This theme joins The Fall Guy theme (and many others) in expressly describing what the show is about. In this case, it mainly reflects the story of station program director Andy Travis (Gary Sandy). After a decent run on CBS, the show became enormously popular in syndication. It was revived for a short run in the early 1990s, and retained the theme (albeit updated a bit, musically).

39. Game of Thrones

2011-2019; by Ramin Djawadi

Uploaded to YouTube by GameofThrones

Based on the hugely successful A Song of Ice and Fire novels by George R.R. Martin, HBO’s Game of Thrones became a worldwide fantasy phenomenon. The music of the show has inspired orchestral concerts and tours. The majestic main theme is by composer Ramin Djawadi, whose body of work includes creating additional music for Hans Zimmer scores for movies like Iron Man, Batman Begins, and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl.

38. Sanford and Son

1972-1977, and for Sanford 1980-1981; “The Streetbeater” by Quincy Jones

Uploaded to YouTube by doop72

The popular Redd Foxx/Demond Wilson sitcom featured the catchy funk of Quincy Jones. Though the song never charted, Jones nevertheless included it in his Greatest Hits collection. The theme was also used for Sanford, a brief revival that Wilson declined to join.

37. The Brady Bunch

1969-1974; by Frank De Vol and Sherwood Schwartz

Uploaded to YouTube by Marcia Brady

The theme from The Brady Bunch serves as a microcosm of our bigger list. Song explains the plot? Check. Co-written by a show creator? Check. Sherwood Schwartz again? Check. Used in revivals of the show? Check. The song certainly gets credit for quickly establishing the premise of a blended family, and it proved popular enough to generate variations or instrumental motifs used in the nine variation spin-offs and continuations of the show. The tic-tac-toe board layout of the opening sequence and the song itself have been parodied many times, including a recent take by the actors of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

36. Good Times

1974-1979; “Good Times” by Dave Grusin and Alan & Marilyn Bergman, performed by Jim Gilstrap and Blinky Williams

Uploaded to YouTube by Yon Legend

Both Sanford and Son and Good Times, along with a couple of upcoming entries on our list, were developed by super-producer Norman Lear. Lear didn’t shy away from controversial topics or blue-collar characters, and Good Times was an exemplar of that. The theme’s lyrics reference the hardships that the Evans family faced in the projects, notably the hard-to-hear-unless-you-know-the-words “hangin’ in a chow line.”

35. Laverne & Shirley

1976-1983; “Making Our Dreams Come True” by Cyndi Grecco

Uploaded to YouTube by Lennie72

If Norman Lear was the king of 1970s sitcoms on CBS, his counterpart at ABC was Garry Marshall. He hit with The Odd Couple and followed with phenom Happy Days. Happy Days generated a remarkable seven spin-offs (two of which were animated). The first, and most successful, was Laverne & Shirley, which followed two single gals who first appeared on Days as friends of the Fonz. Laverne herself, Penny Marshall (Garry’s sister), contributed the hopscotch chant that comes before the song in the opening credits.

34. The Facts of Life

1979-1988; by Al Burton, Alan Thicke, and Gloria Loring

Season 1

Uploaded to YouTube by Steven Brandt

Season 2 onward

Uploaded to YouTube by Steven Brandt

Much like the show, the theme had two distinct versions. The first version was used for season 1 and featured star Charlotte Rae and a number of the seven featured young ladies trading lines. When the show was retooled for season 2 (which included replacing four of the girls — one of whom was a young Molly Ringwald — with Nancy McKeon’s Jo), portions of the lyrics were rewritten, including the addition of the more famous “You take the good, you take the bad” opening line. From season 2 on, the theme was performed by co-writer Loring, known for her role on Days of Our Lives and her later hit song Friends and Lovers.

33. Diff’rent Strokes

1978-1986; by Al Burton, Alan Thicke, and Gloria Loring

Uploaded to YouTube by TeeVees Greatest

The Facts of Life actually spun off from Diff’rent Strokes, so it was logical to have Burton, Thicke, and Loring write both themes. However, on this earlier program, Thicke sang lead. This was just one facet of Thicke’s incredibly diverse career that ran the gamut from composer to singer to talk show host to lead actor on the successful sitcom Growing Pains.

32. The Mary Tyler Moore Show

1970-1977; “Love Is All Around” by Sonny Curtis

Uploaded to YouTube by Brian Harrell

It’s hard to overestimate the impact of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Having a single career woman in the lead was a huge deal at the time, and the incredible cast and crew (including creator and sitcom writing/directing legend James L. Brooks) powered the show to 29 Emmy wins over its run. The Sonny Curtis theme became an empowering anthem, and Mary’s hat toss at the end of the opening is an iconic TV moment. The theme has been covered by a number of artists, including Joan Jett and Minneapolis-based Hüsker Dü, who parodied the show’s opening in their music video; Hüsker Dü frontman Bob Mould still performs the song as an encore on his current solo tours.

31. The Sopranos

1999-2007; “Woke Up This Morning (Chosen One Mix)” by A3

Uploaded to YouTube by acer_16

British electronic act Alabama 3 (called A3 in the U.S. to avoid confusion with country band Alabama) blended their modern approach with the mood of a bluesy murder ballad. The tune, set against a spare opening of mafia underboss Tony Soprano driving home through New Jersey, evokes the dark tone of the series.

30. The Dukes of Hazzard

1979-1985; “Good Ol’ Boys” by Waylon Jennings

Uploaded to YouTube by will244

Country legend Waylon Jennings nailed the spirit of a show about car chases and misadventures with his plot-explaining anthem. Extremely popular, the single reached No. 21 on the pop chart and hit the top of the Hot 100 Country chart in 1980. Jennings also served as narrator for the series.

29. All in the Family

1971-1979; “Those Were the Days” by Lee Adams, Charles Strouse, and Roger Kellaway, performed by Caroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton

Uploaded to YouTube by BlastFromTheePast

The No. 1 show in America from 1971 to 1976, and another of Norman Lear’s murderer’s row of monster CBS hits, All in the Family’s plots turned on the clashes between bigoted Archie Bunker (O’Connor); his ostensibly silly but deceptively wise wife, Edith (Stapleton); their liberal daughter, Gloria (Sally Struthers); and her ever-more-liberal husband, Michael “Meathead” Stivic (Rob Reiner). The show had five definitive spin-offs (a couple of which spun off their own shows). The theme featured leads O’Connor and Stapleton opining on better days (at least as how Archie saw them).

28. The Jeffersons

1975-1985; “Movin’ On Up” by Jeff Barry and Ja’net Dubois, performed by Dubois

Uploaded to YouTube by Matt Laufenberg

One of the spin-offs from All in the Family featured the extremely popular neighbors, George and Louise Jefferson, played by Sherman Hemsley and Isabel Sanford. The theme charts the Jefferson’s move from their old neighborhood to their new high-rise thanks to the success of George’s dry-cleaning chain. The Jeffersons holds the distinction of having the most seasons of any sitcom with a primarily African-American cast. Musical side-note: the late regular cast member Roxie Roker (Helen Willis) is the mother of rock star Lenny Kravitz.

27. The Andy Griffith Show

1960-1968; “The Fishin’ Hole” by Earle Hagen, Herbert Spencer, and Everett Sloan

Uploaded to YouTube by GreatestShowsOnEarth

One of the most memorable themes ever is one of the simplest. Largely whistled (by Hagen), actual musical instruments don’t come in until about halfway through the 30-second theme. The tune is absolutely unmistakable.

26. The Muppet Show

1976-1981; “The Muppet Show Theme” by Jim Henson and Sam Pottle

Uploaded to YouTube by killerwattvids

Though certain parts of the song changed over the course of the five seasons, the core of “The Muppet Show Theme” remained the same. The song was performed by creator Henson, Frank Oz, and other operators via their various characters. In a move similar to the later “couch gag” on The Simpsons, each episode’s theme song ended with a different noise emanating from Gonzo’s horn, usually followed by a punch line.

25. Danger Man/Secret Agent

1960-1962, 1964-1968; “Secret Agent Man” by P.F. Sloan and Steve Barri, performed by Johnny Rivers

Uploaded to YouTube by 14Undertaker31

Danger Man was a British TV series featuring Patrick McGoohan as secret agent John Drake. It had a short U.K. run but became an unexpected hit in the U.S. during summer reruns under the name Secret Agent. Part of the new success was owed to the rocking U.S. theme song, which became a No. 3 hit on the Hot 100. This prompted a resurrection of the show that ran from 1964 to 1968. At the end of the final season, McGoohan left and launched the unofficial sequel, cult classic sci-fi show The Prisoner.

24. Space: 1999

1975-1977; by Barry Gray and Vic Elmes

Uploaded to YouTube by 11db11

Space: 1999 didn’t have a long run, but it left behind several generations of fans. The show was led by Martin Landau and Barbara Bain (who were married at the time and had starred in Mission: Impossible together) and shot in the U.K. The premise turned on the inhabitants of Moonbase Alpha, who have to try to survive when the moon is knocked out of Earth’s orbit. The theme opens with portentous classical sounds, and then kicks into full-on sci-fi disco. It’s very of its time, but awesome lives forever.

23. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air

1990-1996; “Yo Home to Bel-Air” by DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince with Quincy Jones

Uploaded to YouTube by Raqraqxox

Someone had the idea to put the wildly charismatic Will Smith, the “Fresh Prince” of hip-hop duo DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, in a sitcom. Someone was a genius. The show was a huge hit and launched Smith into an even more successful film career. The theme, which is actually called “Yo Home to Bel-Air,” puts the show’s premise and Smith’s talent on full display.

22. The Golden Girls

1985-1992; “Thank You for Being a Friend” by Andrew Gold, performed by Cynthia Fee

Uploaded to YouTube by Steven Brandt

Though most people associate this song with the TV series, Gold’s original recording of Thank You for Being a Friend hit No. 25 on the Hot 100 in 1978. Re-recorded for the series by Fee (and re-recorded again for later spin-off, The Golden Palace), the tune is now indelibly associated with Dorothy, Sophia, Rose, and Blanche.

21. Doctor Who

1963-1989, 1996, 2005-present; by Ron Grainer

Uploaded to YouTube by Doctor Who

It’s been 56 years since the first Doctor stole the TARDIS and began his adventures through space and time. Played today by Jodie Whittaker, the official 13th doctor (and first female), the character continues to command a devoted international following. The theme was composed by Grainer, but the studio wizardry of Delia Derbyshire and Dick Mills incorporated the electronic sounds that made it legendary. Though there have been a number of versions, you know that theme when you hear it.

20. The Monkees

1966-1968; “(Theme from) The Monkees” by Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart, performed by The Monkees

Uploaded to YouTube by Merovee999

We’ve covered the origin of The Monkees more than once in this magazine. The theme itself was written by Boyce and Hart, the songwriting team that also composed other Monkees tunes, like “Last Train to Clarksville” and “(I’m Not Your) Stepping Stone,” as well as other 1960s hits like “Come a Little Bit Closer” for Jay and The Americans.

19. Sesame Street

1969-present; “Can You Tell Me How to Get to Sesame Street?” by Joe Raposo

Uploaded to YouTube by Divi Cents

What can you say about Sesame Street? A giant of educational programming and the generator of countless beloved characters (and the proving ground for The Muppet Show), the show has won an unbelievable 189 Emmy awards during its run. The theme itself ran in its original form until 1992; since then, occasional and subtle changes in pacing and instrumentation have been made, but it’s still a classic.

18. Hill Street Blues

1981-1987; by Mike Post

Uploaded to YouTube by Brill Videos

Created by Steven Bochco and Michael Kozoll, Hill Street Blues changed television almost immediately. From its diverse cast to its multi-episode stories to its handheld cameras and innovative editing, the show broke ground in different levels of writing and production, earning 98 Emmys during its run. The instrumental theme by veteran TV composter Mike Post hit No. 10 on the Hot 100 in 1981.

17. The Love Boat

1977-1986; by Paul Williams and Charles Fox

Uploaded to YouTube by Analog Child

Singer Jack Jones performed the title tune that was used for the first eight seasons of the show; Dionne Warwick did the version used in the final season. The Love Boat was part of ABC’s hugely successful Saturday night lineup, airing ahead of fellow hit Fantasy Island. The two series even had a crossover episode; another episode guest-starred Charlie’s Angels. The show also had the distinction of being one of the few hour-long American series to employ a laugh track.

16. Miami Vice

1984-1989; by Jan Hammer

Uploaded to YouTube by AMB Production TV

A No. 1 hit for Jan Hammer in 1985, the Miami Vice theme was as cutting-edge and of-the-moment as you could find on TV. Packed to bursting with synth, electric guitars, and Cuban rhythms, the piece aimed to evoke the titular city, action, and fashion all at the same time. It won two Grammys in 1986. Music was an integral element of the show, with classic and current hits splashed across every episode of its run.

15. The X-Files

1993-2002, 2016-2018; by Mark Snow

Uploaded to YouTube by Chris Burns

We revisited the history of The X-Files in September 2018 for the show’s 25th anniversary. At the time, we commented on the “famously spooky opening theme.” Mark Snow composed the theme; it was used in the nine original seasons, the two revival seasons, and in both theatrical films.

14. Wonder Woman/The New Adventures of Wonder Woman

1975-1979; by Charles Fox and Norman Gimbel

Uploaded to YouTube by Steven Brandt

Wonder Woman had an unusual production history. Given the greenlight for a series after a TV movie, actress Cathy Lee Crosby was replaced with Lynda Carter. The first season, set during World War II, ran on ABC. CBS picked up the show for the next two seasons, but moved the setting to the 1970s. Accordingly, the iconic theme song, with its World War II references, was retooled as an instrumental. Unlike some superhero themes that would never be used today, the classic still pops up in places like Wonder Woman’s guest appearance on Batman: The Brave and the Bold.

13. The Greatest American Hero

1981-1983; “Theme from the Greatest American Hero (Believe It or Not)” by Mike Post and Stephen Geyer, performed by Joey Scarbury

Uploaded to YouTube by 888eve

An action-comedy about a high school teacher who gets a superhero suit from aliens (but loses the instructions), The Greatest American Hero had a decent three-season run in the early 1980s. The theme song was an even bigger hit, going to No. 2 on the Hot 100 in America and charting in five other countries. It ended up being the 11th biggest hit song of 1981 in the States.

12. Twin Peaks

1990-1991, 2017; “Falling” by Angelo Badalamenti and David Lynch

Uploaded to YouTube by Long Evenings

Visionary film director David Lynch did the unthinkable in 1990. Along with writer Mark Frost, he created a TV series for a major broadcast network. The short first season was a critically praised, must-watch hit. However, difficulties with the network, a loss of momentum after the revelation of Laura Palmer’s killer, and constant time-slot disruptions (due, in part, to the Gulf War) led to the show not being renewed after the second season. Lynch, Frost, and much of the cast revived the series on Showtime in 2017. The theme, Falling, was derived from a song that Lynch and his frequent collaborator Angelo Badalamenti wrote for singer Julee Cruise. A single with both the instrumental and Cruise versions charted in over a dozen countries between 1990 and 1991.

11. Peter Gunn

1958-1961; by Henry Mancini

Uploaded to YouTube by 71superbee3

One of the most instantly recognizable pieces of television music ever created, the Peter Gunn theme brought Henry Mancini an Emmy and two Grammys, including Album of the Year in 1959 for The Music of Peter Gunn. The album itself hit No. 1 on the Billboard Album Chart. Frequently covered and used as a musical cue in film, the song received a second life in the 1980s as the music for the enormously popular Spy Hunter video game.

10. Happy Days

1974-1984; by Norman Gimbel and Charles Fox

Uploaded to YouTube by Ldolcebimbp francesco.C

It’s not often that a second theme song becomes the one that’s most associated with a show. The first season used a re-recorded version of Bill Haley and His Comets seminal Rock Around the Clock for the opening, with the Happy Days theme (with Jimmy Haas on lead vocals) playing over the end credits. From the second season to the tenth season, the Happy Days theme was moved to the front; the 11th season featured an updated version with Bobby Arvon on lead vocals.

9. M*A*S*H

1972-1983; “Suicide Is Painless” by Johnny Mandel with lyrics by Mike Altman

Uploaded to YouTube by Carolina Trains

The TV series spun out of the successful 1970 film by Robert Altman; that movie featured a version of Suicide Is Painless complete with lyrics. Those lyrics were written by the director’s son, who was only 14 at the time. The elder Altman would later note on The Tonight Show that the song’s use in the film and TV series had subsequently earned his son over $1 million in royalties.

8. The Twilight Zone

1959-1964, with revivals in 1985, 2002, 2019; by Marius Constant

Uploaded to YouTube by Master Hoshi

We’re breaking our own rule by including an entry from the forthcoming Greatest Spoken-Word Themes list here, but we have to do it. This is another theme that switched between seasons. While season one did contain Rod Serling’s immortal speechifying in the intro, it had fairly standard music by Bernard Herrmann. With the second season, the theme gave way to the familiar, unsettling theme by Marius Constant.

7. The Addams Family

1964-1966; by Vic Mizzy

Uploaded to YouTube by Steven Brandt

A piece that’s destined to live forever on Halloween compilations and in sports arenas, The Addams Family theme might contain the most famous double-snaps of all time. It’s also one of the few lasting themes to prominently feature harpsichord. Fun note: the spoken “neat,” “sweet,” and “petite” were supplied by Lurch himself, Ted Cassidy.

6. Mission: Impossible

1966-1973, 1988-1990; by Lalo Schifrin

Uploaded to YouTube by Themes and Titles

Two TV series. Six movies (and counting). Covers by members of U2. Innumerable references in popular culture. Lalo Schifrin’s Mission: Impossible is one of the gold standards for theme music. With subtle variations, it was used in the original series, the 1988 revival, and at varying points in each film of the Tom Cruise franchise. Impossible Missions Force trivia tidbit: In the 1980s series, Phil Morris plays the son of the character that his father, Greg Morris, played on the original series.

5. Batman

1966-1968; by Neal Hefti

Uploaded to YouTube by Patrick Rooney

Jazz composer Neal Hefti was nominated for three Grammys and won one for his work on Batman. The memorable track with a single lyric (“Batman!”) paired wonderfully with the animated intro, evoking the campy and comedic tone of the show. Thanks to the guitar and bass tones on the track, it’s considered an entry in the surf rock genre; it’s been covered by acts like Jan & Dean, The Who, The Kinks, The Jam, and Eddie Vedder (with his daughter, Harper).

4. Cheers

1982-1993; “Where Everybody Knows Your Name” by Gary Portnoy and Judy Hart Angelo, performed by Portnoy

Uploaded to YouTube by TeeVees Greatest

One of the great statement-of-purpose themes, “Where Everybody Knows Your Name” received an Emmy nomination in 1983. Widely praised by a variety of publications and websites, it’s generally considered among the best of TV show theme music throughout the history of the medium.

3. S.W.A.T.

1975-1976, 2017-present; “Theme from S.W.A.T.” by Barry De Vorzon, performed by Rhythm Heritage

Uploaded to YouTube by 11db11

A spin-off of the hit show The Rookies, S.W.A.T. only lasted two seasons. This was, in part, because of controversy surrounding the level of violence on the show. The indisputably awesome funk-driven theme song, however, was a No. 1 hit for Rhythm Heritage and sold over a million copies. A version of the music was used in the 2003 film adaptation, which starred Samuel L. Jackson. In 2017, a CBS television reboot starring Shemar Moore debuted; it uses an updated version of De Vorzon’s theme by Robert Duncan.

2. The Rockford Files

1974-1980; by Mike Post and Pete Carpenter

Uploaded to YouTube by 11db11

The effortless cool of James Garner as P.I. Jim Rockford was conveyed in this terrific number by Mike Post and Pete Carpenter. Incorporating electric guitar and some very 1970s keys, “The Rockford Files” had a four-month chart run in 1975, eventually hitting No. 10. It also won a Grammy in 1975.

1. Hawaii Five-0

1968-1980, 2010-present; by Morton Stevens

Uploaded to YouTube by bfelten

Sometimes the best is just the best. Endlessly covered, a staple of marching bands (it’s the unofficial “fight song” for the University of Hawaii), and awesome enough to be used again for a series remake 20 years later (the original was re-recorded with some of the same musicians), we’re confident in saying that “Theme from Hawaii Five-0” is the greatest. Apart from composing film and television music, Morton Stevens was Sammy Davis Jr.’s arranger and occasional conductor from the 1950s until Davis’s death in 1990. Morton himself passed away in 1991, but we have a feeling that this tune is never going away.

Read Part 2: Spoken-Word here.

Featured Image: Shutterstock

Five Overlooked Halloween Specials

The holiday TV special holds a special place in the hearts of kids of all ages. Every occasion seems to merit a number of animated or live-action celebrations, including special episodes of ongoing series. Halloween can lay claim to an almost endless parade of cartoon and live-action interpretations, some of which have gotten lost in the folds of time. It would be a monumental task to exhume all the fan favorites that have drawn small audiences over the years, so we focus on five overlooked Halloween specials in particular — including one that was written by one of the greatest fantasy writers of all time.

Halloween Is Grinch Night (1977)

Eleven years after the huge success of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the Grinch returned in this trippy Halloween installment. While there are differences of opinion among critics as to whether this is a sequel or a prequel, what is certain is that it’s a creepy, offbeat little fable. The animation and overall vibe are different from the Christmas story we know — it was directed by Gerald Baldwin rather than Chuck Jones. It also features more songs and a generally surrealistic tone. It might not be everybody’s slice of roast beast, but it’s certainly an interesting one to check out.

Halloween Is Grinch Night

A Scooby-Doo Halloween (2003)

Presented as the sixth episode of season two of What’s New, Scooby-Doo?, this special finds the gang heading to the small town of Banning Junction to spend Halloween with Velma’s family and see KISS. Yes, you read that correctly. The famous rock band lends their voices and music to the proceedings as the gang tries to solve the mystery of some larcenous and destructive robot scarecrows. Viewers get treated to an animated performance of “Shout It Out Loud,” as well as one classic KISS dialogue exchange: When the robot scarecrows storm their show and guitarist Tommy Thayer wants to know the plan, Paul Stanley says, “What we always do! Keep playing until the cops come!”

KISS plays “Shout It Out Loud” in A Scooby-Doo Halloween.

The Midnight Hour (1985)

Jack Bender’s career in television remains something even experienced directors would envy. He’s directed many episodes of classic TV, such as The Sopranos, Game of Thrones, Alias, Felicity, Beverly Hills 90210, and 36 episodes of Lost, including the series finale. Among all of that inarguable greatness rests a dusty gem that has a hardcore horror cult following. The Midnight Hour is a made-for-TV comedic horror film with a heavy emphasis on the music of the 1960s; it additionally features one song from The Smiths and an original number, “Get Dead.” One of the most interesting things about it is its unique tone, combining music, witchcraft, zombies, vampires, friendly 1950s ghost cheerleaders, and teen comedy. While it might not be to everyone’s taste, it’s definitely an early signpost that Bender was capable of making fantasy elements work on screen.

The Midnight Hour

A Wonderful World of Disney Trio (1997, 1982, 1983)

Disney films and specials have been running as an anthology brand on television since 1954. Beginning with Walt Disney’s Disneyland in that year and moving through a series of name changes that generally include World in the title, the programming umbrella has often included holiday programming and compilations. Disney put three different specials into rotation in the late ’70s and early ’80s as distinct episodes, one of which was later made available on home video:

- Halloween Hall o’ Fame aired in 1977, featured Jonathan Winters as host, and included four classic cartoons: “Trick or Treat,” “Lonesome Ghosts,” “Pluto’s Judgement Day,” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

- Disney’s Halloween Treat aired in 1982 and combined some of the pieces from Hall o’ Fame with additional animated segments and a pumpkin puppet host; it ran numerous times and received a VHS release.

- In 1983, A Disney Halloween pushed the length to 90 minutes and combined a number of features into one special. The Magic Mirror hosts a tour through 23 animated segments, including previously used Halloween-themed bits and excerpts of villain scenes from various Disney films. It ran on both ABC and various Disney channels into the late ’90s.

While no exact reproductions of these specials are available on DVD today, and only portions are available on YouTube, the pending introduction of the Disney Streaming Service certainly opens up the possibility that they’ll be seen in their entirety again.

A compilation of Disney Halloween specials on YouTube.

The Halloween Tree (1993)

A giant of fantasy and science fiction, Ray Bradbury wrote 27 novels and more than 600 short stories. He was fascinated with Halloween and childhood, returning to those subjects in his writing in novels like Something Wicked This Way Comes and collections like The October Country. Beginning in 1950, he published 14 short stories and two poems in The Saturday Evening Post, and later served on its fiction board.

Based on Bradbury’s classic 1972 novel with a screenplay written by the fantasy master himself, The Halloween Tree first aired in 1993 and captured an Emmy for Outstanding Writing in an Animated Program. The story follows a group of children as they time-travel through the traditions that led up to Halloween in an effort to rescue their friend. Bradbury himself narrates, and the voice of antagonist Mr. Carapace Clavicle Moundshroud is provided by none other than Leonard Nimoy. The film enjoys some perennial popularity through nearly annual showings on Cartoon Network but still manages to fly under the mainstream radar. Interestingly, it received six separate VHS releases between 1994 (including two that came with the book) and 2000. It’s been released twice on DVD, mostly recently in 2016.

The Halloween Tree

https://files.saturdayeveningpost.com/uploads/reprints/The_Happiness_Machine/index.html

As a special Saturday Evening Post bonus, you can read “The Happiness Machine” from Ray Bradbury’s collection Dandelion Wine.

Featured Image: The Halloween Tree home video cover art; ©Hanna-Barbera/Turner Home Entertainment