Hans Zimmer is one of Hollywood’s most successful and innovative composers, with soundtracks for over 150 films ranging from Driving Miss Daisy to Gladiator to the current Oscar frontrunner, Dunkirk. Zimmer’s original score for The Lion King earned him an Academy Award; he’s been nominated for eight more.

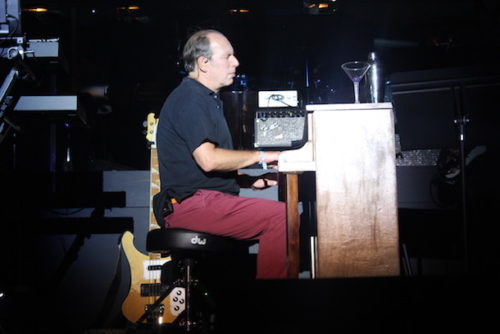

The celebrated musician fought past his life-long stage fright to give a show-stopping performance on last year’s Grammy Awards, providing guitar riffs for Pharrell Williams. That inspired a world tour, giving enthusiastic audiences live performances of the powerful musical moments they first experienced in a dark theater. He was a surprise hit at Coachella alongside mega-stars like Kendrick Lamar and Lady Gaga.

Since he was a kid, Zimmer just wanted to make music. “My father died when I was really young, so growing up, music was a refuge for me,” he remembers.

“Then when you become a teenager, it turns into a completely different thing. It becomes — how am I going to say this politely? – when it comes to girls, it’s better than talking to them.”

Jeanne Wolf: Now that your live show is a hit, can I finally call you a rock star?

Hans Zimmer: I don’t think I’m a rock star but it is exciting to go out there and play in front of people instead of hiding behind a movie screen. I have a feeling that it might have made me a better composer, because I was actually able to feel the audience in real time rather than what we do making movies, where we’re basically guessing. We’re hoping that the soundtrack we’re creating is going to resonate and add to the experience for people in a theater. As soon as I finish a movie, I forget everything that I’ve written. I have to forget, because otherwise you don’t make room for the new ideas. So when we are playing the old soundtracks every night on tour, we are reinventing and sort of improving them. That’s a luxury you don’t have when you’re making a film.

JW: There has been a remarkable reaction to your compositions for the movie Dunkirk. The suspense-driving track is so unique that it’s hard to describe. Where did that come from?

HZ: Usually I start out by writing a tune, but there’s no melody in the Dunkirk soundtrack. The whole idea was how do we keep the tension going? How do we play with the concept that time is running out? Everything had to live up to that. For months I would go to sleep, and I would start dreaming the scenes, and then I would wake up and go back to the studio. I never had any reprieve from it. When I actually went on the Dunkirk location, the weather had turned really nasty. I was on that beach, and it was unbearably cold. Sand was blowing at you from every direction, the poor actors were standing there in the freezing wind, and there’s [director] Chris Nolan charging down the beach. So when I was composing, I felt Chris’ hand on my hand like he was pressing the keys down with me. I really tried as much as possible to make it his score.

JW: With all you’ve done, I always love your enthusiasm.

HZ: The operative word in music is play. The thing that we really carry over from our childhood is that sense of playfulness. I think all that happens is we try to get very serious about being very playful. The hours we keep are absurd. I’m forever begging forgiveness of my children for not being around, but on the other hand, they love being in my studio. I think what my kids have seen through their whole childhood watching me work is people being passionate about what they’re doing and having fun, having a sense of humor about a catastrophe (which isn’t really a catastrophe). Making movies, there’s never enough time, never enough money, it’s raining on the day you need sunshine, and it’s sunny on the day you’re trying to shoot a rain scene. I sort of make it my job in a funny way to remind the filmmakers what the original dream was and enhance it. I think about what made every body try to do the impossible.

JW: I have interviewed a lot of rock stars, and they talk about that high when you connect with the audience. Did you experience that kind of connection?

HZ: Constantly, constantly. Yes, absolutely. I mean, I really felt that the audience was hungry to have a different experience, and we managed to give them that. They had a sort of idea what it would be like, but to be honest, no one has ever done it this way, so the element of surprise was really nice, and the element of surprise for me was really nice. Just how open they were and how welcoming they were. I asked everybody for advice before this, and people kept saying that the attention span of young people is really bad these days, and you have to play short pieces. I don’t know. “Pirates” is 14 minutes long. “The Dark Knight” thing is 22 minutes long. These aren’t short pieces, and the audience really stuck with it. The audience loved that we would take them on a journey and take them back into the world.

JW: How great was that? You are still so excited about what you do. I love your participation. Could you describe what drives you now?

HZ: Yes. Actually what was interesting for this tour was going back. Obviously, I had to go back in time and look at all of the pieces that I’ve written. The tour was playing the old soundtracks again, and every night we were reinventing and sort of improving them. All of the stuff that you can’t do because you have time restrictions. A movie needs to be finished.

JW: And you have to fit to the scene.

HZ: Exactly. So what drives me is basically that I know I can write a better piece of music. I know I’m still learning and figuring it out. Dunkirk was such a learning curve because we really reached through every rule book. It wasn’t even about “Let’s invent a new way of doing this.” It was “Let’s invent and then we actually have to learn how to do it.” Every day was a day of having no idea of how to get around the next corner.

JW: Listening is a big part of your art. Do you think you’re a good listener with the people close to you? Because it’s hard to be nowadays.

HZ: I think I try to be a good listener. My children keep telling me that — so that’s the greatest compliment that I can get.

JW: That is a great compliment. It means you’re hearing me and you understand me.

HZ: Yes, exactly. I suppose you know, partly the reason I have the career I’ve had is that I listen to my directors. I don’t listen when they tell me what to do. I listen to the subtext. I listen to what the —. Look, every movie starts with the same thing. Somebody phones you up and says, “I want to tell you a story,” which is already a great start. What a great life — these people telling me stories.

JW: Has there been a director — there must be more than one — whom you butt heads with or think you’ll never be able to please?

HZ: Oh totally. Often. Those are the directors that I’ve worked with more than once. Gore Verbinsky and I would go at each other pretty badly. Terry Malick once said to me, “The way we speak to each other, only brothers can speak to one another that way.” I remember I was doing Hannibal, working with Ridley Scott. It was about 11 o’clock on a Sunday night. They had just gotten back from shooting, and we were in the cutting room looking at a shot of Julianne Moore’s face with a tear running down her cheek, and I say, “Oh yeah, she’s crying because she’s in love with him.” And Ridley goes, “No. It’s a tear of disgust.” Then we start arguing about this and it got sort of feisty, and suddenly we’re on our feet and we’re in each other’s faces and I just stepped back and I thought, Wow. This is amazing. It’s Sunday night at 11 o’clock and grown men are passionately arguing about what a tear running down a woman’s cheek means.

JW: Have you figured out where you got your courage?

HZ: Well, I think from the people who were kind and took me on when I had no career. Stanley Myers, the great film composer who wrote The Deer Hunter, he took me under his wing. One of the first people I ever got to work with. I also learned a lot from George Martin.

JW: Oh! The Beatles man.

HZ: I remember the first time I ever got paid for doing music was for George Martin. Weirdly, I remember the check more than the sessions. It was astonishing after struggling. I can’t tell you how many tins of baked beans I ate because it was the only thing I could afford. Somebody was actually paying me to make music.

JW: Wow. How many tins of baked beans did it take to be here?

HZ: Years.

JW: The people don’t understand that the memory of that gives you courage, too.

HZ: My daughter asked me once, “Dad, what was it like being a poor artist?” I realized that I’d never thought about it. It never occurred to me that I was a poor artist because everybody around me was in the same boat. That just seemed to be life, and we were making music all day long. I still have really bad eating habits. I usually don’t have lunch because I’m in the middle of writing something. Do I live a normal life? No. Look, I’m coming up to my 60th birthday, and I think it has worked out so far.

JW: Yes. Oh, boy, has it. We want a full life, but do we really want what someone else defines as a normal life? No. Not somebody who goes to play Coachella.

HZ: No, and the world is shifting tremendously with technology and stuff like this. So many things which we took for granted that came from the Industrial Revolution — like job security — are just disappearing, and I think at the end of the day the one thing that isn’t disappearing is to be an artist. To write poetry, to paint a painting, to write music.

JW: Could you have dreamed that you would be as excited, as turned on, as buzzed about what you do now as you were in the beginning — or more!

HZ: Yes. I don’t know why. Well actually, I have to say, and every director knows this about me, I do a little thing where I ask myself when I get up, “What if I was to go to the studio today to make music, and the answer is ‘No, we need to find somebody else.’” But it hasn’t happened yet. Literally, the last four weeks of the tour we were so tired, but all I was doing was planning the next piece of music and the next adventure. That’s just how I’m built, and everybody around me is sort of built that way as well.

An abridged version of this article is featured in the November/December 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now