The story of how and why George Gershwin wrote Rhapsody in Blue in just a month is one of the legends of American music. It goes like this:

Sometime in 1923, bandleader Paul Whiteman mentioned to Gershwin that he was thinking about putting together a concert of modern music that incorporated jazz elements, and he asked if George might be interested in writing and performing a jazz piano concerto for such a concert. Gershwin said he was. A busy man, Gershwin more or less forgot about the concerto until the beginning of 1924, when George saw an announcement in a newspaper stating that Whiteman had scheduled a concert about a month later and that Gershwin would premiere his new piece there. Until that point, Gershwin hadn’t written a single note of the piece, but with intense labor and the help of Whiteman’s arranger, Ferde Grofé, Rhapsody in Blue was finished in time for rehearsals.

Like many legends, as the story was told and retold — even by some of its main characters — details shifted. In broad strokes, though, this is true.

The Overture

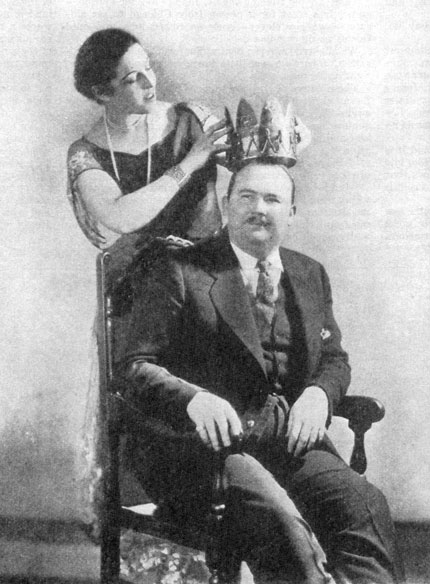

It’s unclear when Whiteman first chatted with Gershwin about writing a new jazz-based piano concerto, and it seems to have been more of a hypothetical case, not an actual commission. Whiteman and his orchestra had returned from its first tour in England in August of 1923. In what can only be described as a fit of hyperbole and publicity, Whiteman was crowned “King of Jazz” at a reception right there at the port. (Though Whiteman’s music incorporated some jazz idioms, his was a dance band — the most popular of the decade to be sure — and its highly orchestrated and watered-down music wasn’t, strictly speaking, jazz.)

Sometime after that, Gershwin, according to biographer Charles Schwartz, casually agreed on principle to write a piano feature for Whiteman and perform the solo himself, though he did so “not without some trepidation about his ability to realize a large-scale work of this kind.”

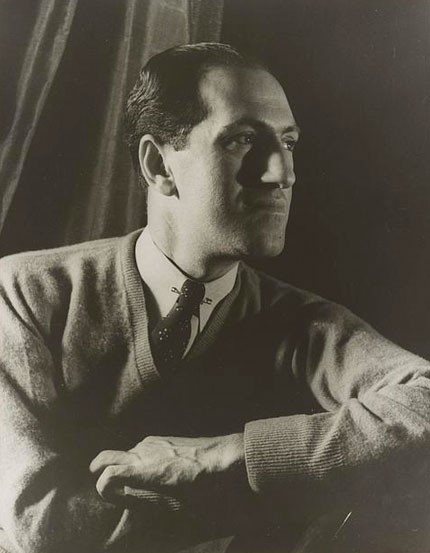

By 1923, Gershwin had made a name for himself in New York primarily as a pianist and composer of Broadway shows, which meant smaller orchestras and tuneful songs that appealed to the common theatergoer. Though Gershwin had been working toward a greater understanding of orchestration, committing to a single large piece for the concert hall would have been a big risk for the 25-year-old. Especially considering how busy he was.

Through most of the second half of 1923, Gershwin was working with songwriter Buddy DeSylva on what would become the musical Sweet Little Devil, which was scheduled to premiere on Broadway in January. And on November 1, 1923, Gershwin was one of two accompanists at a concert given by Canadian soprano Éva Gaulthier at New York’s Aeolian Hall.

Gaulthier’s “Recital of Ancient and Modern Music for Voice” featured six groupings of pieces representing different time periods and nationalities. The title was an intentional misnomer; the most “ancient” pieces on the concert were two written by the 17th-century composer Henry Purcell; every other piece on the program was written in the 19th and 20th centuries, including works by then-living composers like Béla Bartók, Arnold Schoenberg, and Paul Hindemith. By organizing the concert not only as a musical event but as a musicological and educational one, Gaulthier hoped to spark more interest and, in consequence, fill more seats.

Five sections of “serious” music were accompanied by classically trained pianist Max Jaffee. The sixth grouping featured popular American songs by Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, and George Gershwin that, because they were written in a different idiom, benefited from an accompanist who knew it well. Gershwin stepped into that role.

The concert was a success and would be repeated in Boston the following January. Gershwin in particular was singled out for praise in the reviews, both as a songwriter and as a pianist.

Gaulthier would later claim that the praise and publicity of her “Recital of Ancient and Modern Music for Voice” was the inspiration for Whiteman’s later concert and set in motion the events that led to the creation of Rhapsody in Blue. November 1 seems too late a date to have preceded Whiteman’s first discussion of a Gershwin piano concerto, but it’s entirely possible that the success of the Gaulthier recital sparked in Whiteman’s mind the central idea around which his own concert would revolve.

But back to Gershwin: With his Broadway career in full swing and his recognition as a top-notch songwriter and pianist well-established, things were going swimmingly for the young musician. And while the usual Rhapsody story is that he had “forgotten” about Whiteman’s request, there is evidence that, from time to time before 1924, he jotted down musical ideas toward a soft goal of someday writing such a piece.

Then on the evening of January 3, 1924, while DeSylva and Gershwin were enjoying a nice game of billiards, George’s brother Ira was looking over an early edition of the next day’s New York Tribune and came across an unsigned news report stating that Paul Whiteman had scheduled a concert for February 12 (not accidentally Abraham Lincoln’s birthday) at Aeolian Hall (he’d wanted Carnegie Hall, but it was already booked) and that George Gershwin was “at work on a jazz concerto” to be premiered there.

Surprised, Ira — who was, to say the least, well-acquainted with what George was up to — showed the announcement to his brother. George was as surprised as he was.

Whether the news report was penned by a reporter, Whiteman’s publicity agent, or Whiteman himself we may never know, but it’s worth noting that Gershwin wasn’t the only musician caught off guard. The report also claimed that Victor Herbert was “working on an American suite” and that Irving Berlin was “writing a syncopated tone poem.” While Herbert delivered, Berlin never wrote such a piece.

The next day, George phoned up Whiteman and, if the stories are to be believed, tried to beg off the commission, claiming that Whiteman had sprung it on him and that there wasn’t enough time to complete such a piece. Whiteman talked him out of it — which is to say, he talked him into writing the piece — in part by offering the aid of his arranger Ferde Grofé.

Prelude to a Rhapsody

Now committed to writing a jazz piece for piano and orchestra, Gershwin considered at first that he might write an extended blues, but soon rejected that idea in favor of a rhapsody. In musical terminology, a rhapsody is a type of epic, freeform composition made up of popular, folk, or patriotic songs. While this type of composition did come from the European musical tradition — Liszt’s several Hungarian rhapsodies were well known then — which would appeal to musicians of a more academic bent, the form also allowed him to focus on writing what he wrote best: popular tunes.

In a story he would often repeat, Gershwin’s ultimate inspiration for Rhapsody in Blue came while riding the train down to Boston for an off-Broadway premiere of Sweet Little Devil (then called A Perfect Lady) on January 7. “It was on the train,” recorded his biographer Isaac Goldberg, “with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang. … I frequently hear music in the very heart of noise. And there I suddenly heard — and even saw on paper — the complete construction of the rhapsody, from beginning to end. … I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America — of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had the definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.”

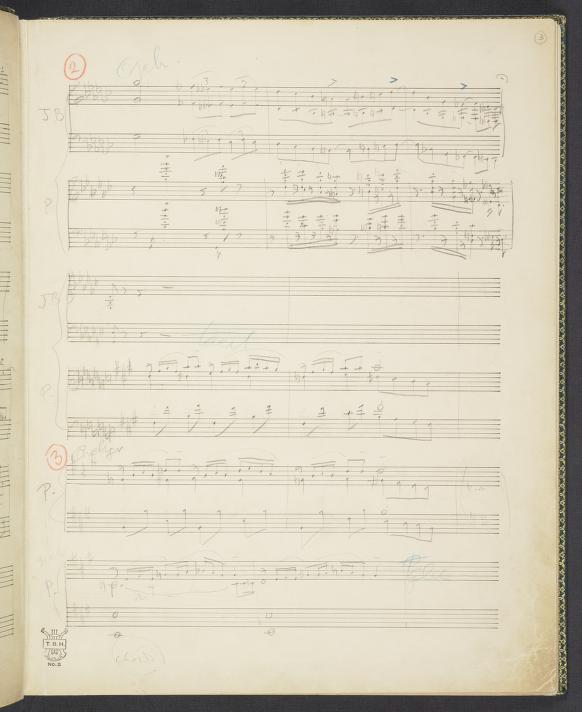

He set out composing Rhapsody in earnest on January 7, a date he wrote at the top of his manuscript. He composed it as a piece for two pianos, one being the solo piano part and the other the accompaniment, which Grofé would arrange for Whiteman’s orchestra. It’s fair to say that Grofé’s arranging played a large role the ultimate success of Rhapsody in Blue. Not only did passing off the orchestration to Grofé take the heat off Gershwin, but because he had been Paul Whiteman’s orchestra arranger for several years, Grofé knew better than anyone the abilities and limitations of individual musicians in the group and could bring out their best.

Gershwin worked on the piece on an old upright piano at the back of the Gershwin apartment on Amsterdam Avenue and 110th Street — where, notes Schwartz, he still lived with his parents, two brothers, and a sister. Grofé would arrive daily to collect what pages George had finished, discuss its development, and share some of Mrs. Gershwin’s Russian tea.

George Gershwin finished his draft of the piece on or around January 25, and Grofé completed the arrangement on February 4, in time for rehearsals.

Crescendo: Building Hype

Paul Whiteman’s concert was billed as “An Experiment in Modern Music” that, according to Whiteman, had a higher purpose: After attending the concert, a panel of distinguished judges — including composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, violinists Jasha Heifetz and Efram Zimbalist, and soprano Alma Gluck — would hand down judgment on a central question: What is American music?

It was pure showmanship, as a quick glance at the panel easily reveals: Rachmaninoff, Heifetz, and Zimbalist were all well-known at the time, but they were all Russian, educated and steeped in European classical musical traditions. Gluck was American-trained but Romanian-born and was likely included only because she was Zimbalist’s wife. These were the musicians who were to speak with authority on the question of American music?

Regardless, the “judges” produced no definitive pronouncement following the performance.

Whiteman’s appeals to authority and celebrity didn’t stop there. Rehearsals for Rhapsody occurred in the mornings at the Palais Royal ballroom where, the preceding evenings, Whiteman and his orchestra would have performed their popular dance music well into the night. To build both chatter and prestige, Whiteman ushered into the rehearsals some of New York’s musical movers and shakers — including music critics William Henderson and Henry Osgood, composers Walter Damrosch and Victor Herbert, and writers Gilbert Seldes and Carl Van Vechten — afterward treating them to a nice luncheon. He also sent out dozens of complimentary concert tickets to musicians, music reviewers, Broadway mainstays, literary greats, and corporate bigwigs, though the regular ticket price was reasonable enough to be accessible to common folk.

And it worked. On the afternoon of Tuesday, February 12, Aeolian Hall was packed, and average New York music lovers were bumping elbows with high-caliber musical celebrities like John Philip Sousa, Igor Stravinsky, violinist Fritz Kreisler, and operatic soprano Mary Garden.

Whiteman had aimed big, and he had planned big — even adding 9 musicians to his orchestra for the event, bringing the total to 23 men. Before the first note was even played shortly after 3:00 p.m. to a standing-room-only crowd, the concert looked to be a rousing success.

Downbeat: The Experiment Begins

But “An Experiment in Modern Music” didn’t start with music. It began, first, with a brief lecture by Paul Whiteman explaining how he believed his project would benefit the art of music as a whole and bring more listeners to the concert hall. “This experiment is to be purely educational,” he noted both on stage and in the extensive (and expensive) program booklet.

(Whiteman also wrote, with Margaret McBride, a three-part series for the Post in 1926 about the history and future of jazz, which you can read online here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.)

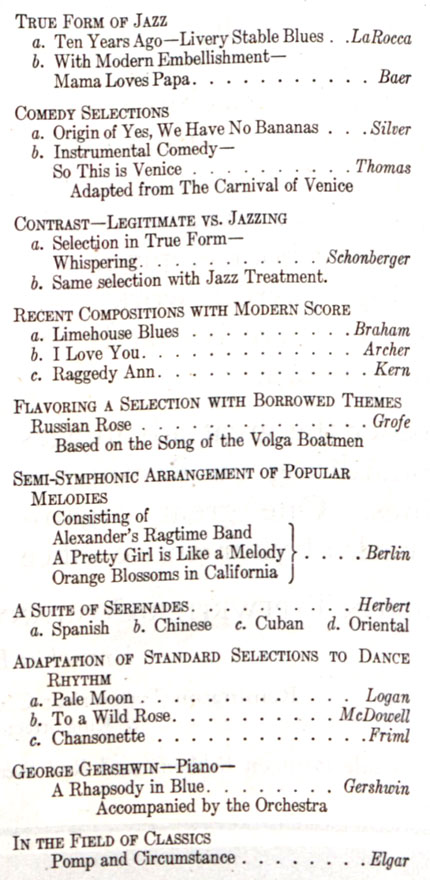

Much like in the program for Éva Gaulthier’s recital, the performances that followed were divided into illustrative sections, ostensibly to plot out the development of jazz in America. Whiteman called the first section “The True Form of Jazz,” revealing from the get-go his ignorance — whether willful or not — of the history of the form: The program opened with a rendition of “Livery Stable Blues,” the first commercial jazz recording ever made; it was written and first recorded by the all-white Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1917.

What followed were largely arrangements of popular tunes (Gershwin’s and Herbert’s were the only new pieces on the concert) meant to showcase the Whiteman orchestra, linked by themes of style and composition. It was a lot of music, with little to surprise the audience.

And then, at some point, the ventilation system at the Aeolian Hall failed. Packed with bodies, the air grew warm and humid. There are various reports that several attendees left early. Rhapsody in Blue was the next-to-last piece on the program.

Much like the altissimo bassoon solo that opened Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Rhapsody in Blue began with an impressive and unexpected flourish, but on the clarinet. It certainly caught the audience’s attention, and Gershwin’s expressive and acrobatic playing held it through to the end. After the final chord was played, there was a moment of absolute silence — as often follows an impressive performance — and then: explosive applause, a standing ovation, and several curtain calls.

Oddly, Whiteman followed up Rhapsody and closed the concert with Sir Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance No. 1, under the heading “In the Field of Classics.” Today, Pomp and Circumstance is most often heard at graduation ceremonies. Published in 1901, it is bereft of jazz or even American influences. If Whiteman had thought to play up the joy and vivacity of American jazz by contrasting it with a dull and repetitive but “serious” piece of music, he couldn’t have chosen a better piece.

Counterpoint: The Critics

Financially, “An Experiment in Modern Music” was a failure. Whiteman told The Saturday Evening Post that he had spent $11,000 (around $200,000 today) of his own money on “Whiteman’s Folly” and realized only $4,000 (around $55,000) in ticket sales. But if you look at how and where he spent his money — the after-rehearsal luncheons, the extra musicians, the low ticket price, the extravagant programs — it becomes clear that his goal wasn’t an immediate financial payoff but a type of publicity that would raise his stature in the industry.

As Gershwin biographer George Schwartz noted, by taking a loss on an “educational experiment” that brought popular and symphonic musicians together, “he emerged as a hero of the arts, an altruistic educator, a music modernist, and a leader of jazz — none of which was really true.” Schwartz, writing in the early ’70s, was no fan of Whiteman, referring to him not as a musician but as a “musical entrepreneur.” But even in 1924, music writers were casting aspersions on his abilities as both a musician and conductor. In his generally positive review of the concert for The New York Times, Olin Downes wrote of Whiteman, “He does not conduct. He trembles, wobbles, quivers — a piece of jazz jelly, conducting the orchestra with the back of the trouser of the right leg.”

Whiteman aside, over the next week, reviews of the concert as a whole were middling or noncommittal, but there was a great amount of praise for Rhapsody. Henry Osgood, reviewer for the New York Courier, was effusive, calling Rhapsody “greater than Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.” Downes noted that “the audience was stirred, and many a hardened concertgoer excited with the sensation of a new talent finding its voice.” Gilbert Gabriel of the Sun called Rhapsody “the day’s most pressing contribution,” noting that “the beginning and ending of it were stunning; the beginning, particularly, with a … drunken whoop of an introduction which had the audience rocking.”

That “drunken whoop” was the now-famous clarinet solo that opens the piece. Gershwin originally notated the opening clarinet flourish it as a straightforward 17-note scalar run from the bottom to near the top of the instrument’s range. It was clarinetist Ross Gorman who transformed that run into a portamento — a continuous glide from one note to the next. During a rehearsal, he had played it that way on a lark, to lighten the mood of the group, but Gershwin loved it so much that he asked Gorman to perform it that way on the concert. That portamento is now the standard, expected opening of the piece.

It wasn’t all praise, of course. There are always negative reviews, and in this instance Gershwin was swimming against some strong cultural currents. The concert as a whole was an attempt to elevate jazz and popular music from the dance hall to the concert hall and show that it deserved as much respect as the “serious” music of the European tradition, a tough sell to concertgoers and music writers who looked down their noses at dance music as a form of entertainment, not “real music.” And reviews of Gershwin’s contribution in particular were sometimes tinged with bigotry — he was, after all, a Jewish musician incorporating Black American jazz idioms into European (i.e., white) music.

Pitts Sanborn, who had attended one of the rehearsals, wrote, “Although to some ears Rhapsody begins with a promising theme well stated, it soon runs off into empty passage work and meaningless repetition.” A later criticism came from Paul Rosenfeld (who had a habit of attacking Gershwin in print), who labeled Rhapsody in Blue “circus-music, pre-eminent in the sphere of tinsel and fustian.” Lawrence Gilman’s review in the next day’s New York Tribune took an even more dramatic bent: “How trite and feeble and conventional the tunes are … how sentimental and vapid the harmonic treatment, under its disguise of fussy and futile counterpoint! … Weep over the lifelessness of the melody and harmony, so derivative, so stale, so inexpressive!”

Molto Vivace: The Rhapsody Takes Off

Regardless of the reviews, Rhapsody in Blue was a hit with people at large, and the publicity surrounding the concert was a boon for both Gershwin and Whiteman. The concert itself would be repeated in the following months, both at Aeolian Hall and then, as a benefit for the American Academy in Rome, at Carnegie Hall — Whiteman’s original aim. Gershwin even made the cover of Time magazine for its July 20, 1925, issue.

It also kicked off a national tour of Whiteman’s company, for which Gershwin continued to perform for a while. Rhapsody in Blue became the group’s signature piece, and Gershwin’s fame and popularity grew well beyond New York City because of it. Whiteman and Gershwin recorded the piece on June 10, 1924, using the all-analog technology available at the time, and then again on April 21, 1927, to make use of the new electronic system of recording. Gershwin also wrote an unaccompanied solo piano version and a two-piano version of Rhapsody which were published by T.B. Harms, and he recorded several rolls for player piano. Grofé arranged new accompaniments in 1926 and 1942, each for a larger orchestra.

Aside from fame, Rhapsody also made Gershwin a rich man. Rhapsody became one of the most adapted pieces ever, with versions arranged for wind quintet, for chorus, for recorder choir, for harmonica and orchestra, and many more. Royalties from the piece flowed into his bank account for the rest of his life, and then, after his death a mere 13 years later from a malignant glioblastoma, to his estate.

It also opened up a musical world Gershwin had only dallied in previously. Before Rhapsody, he had built a career as a songwriter and pianist for the theater; after the success of Rhapsody, he aimed his sights on concert halls, writing larger, more complex pieces that melded jazz sensibilities and popular tunes with traditional symphonic music.

Porgy and Bess, largely considered Gershwin’s magnum opus, might not have been possible without Rhapsody in Blue.

Coda: The Tune’s the Thing

Why does Rhapsody in Blue have such staying power? Certainly it requires the type of virtuosic playing that is just astonishing to experience. And it’s acrobatic, too — hands leaping up and down the keyboard, now crossing right-over-left — so that it is almost as enjoyable to watch as to listen to.

But the greater reason has to do with its form — which ironically has been a common source of criticism of the piece. Composing it as a rhapsody — as opposed to a sonata or rondo or fugue or other musical form — allowed Gershwin to focus on creating exciting and memorable tunes, without extensive harmonic development. And Gershwin was a master at writing catchy tunes.

Even Leonard Bernstein — who twice recorded Rhapsody and referred to Gershwin as his idol — said, “The Rhapsody is not a composition at all. It’s a string of separate paragraphs stuck together — with a thin paste of flour and water. … You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on bravely as before. You can even interchange these sections with one another and no harm done.”

The truth of this assertion played out in the very first recording of Rhapsody, with Gershwin and Whiteman in 1924. In order to fit it on the two sides of a 78 rpm record, sections were omitted from the original 15-minute piece to bring it down to 9 minutes. But it was still Rhapsody in Blue.

Bernstein’s comments, however, were meant to be explanatory, not derogatory. In the same interview, he said, “I find that the themes, or tunes, or whatever you want to call them, in the Rhapsody are terrific — inspired, God-given. … I don’t think there has been such an inspired melodist on this Earth since Tchaikovsky, if you want to know what I really feel. I rank him right up there with Schubert and the great ones.”

Those tunes sink into the listener’s psyche, and you don’t need a degree in musicology to understand them. When you hear a good performance of Rhapsody in Blue, especially a live one, not only do you partake of the excitement, and energy, and immediacy of the piece, but you get to take those tunes with you when you go. Even a week later, you might find yourself humming them. Rhapsody becomes a part of you and, while you hum or whistle or tap out the rhythms on your desk with a pair of pencils, you become a part of it.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Rhapsody’s composition and premiere, and groups around the world are staging their own performances of the piece to mark the occasion. While dozens of recordings are available, there’s nothing quite like hearing it live from the fingers of a skilled pianist. I encourage you to find and attend a performance near you — or two, or three — and experience Rhapsody in Blue for yourself.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Oh “Rhapsody in Blue!” As a child I would listen to it. As a teen, I would envy my neighbor who played it. As a twentyish, I vowed to play it myself. (Never did.) Now at 80, I listen to Leonard Bernstein play it and conduct.

Never lost fascination with the composition and the emotion of it. So New York. So America. Thank you, Gershwin.

What a wonderful in-depth, behind the scenes look at this George Gershwin classic at 100. It’s a very enjoyable musical ride I just listened to before reading the article, to immerse myself in it first. It seems unlikely there was another single song/piece that had such an interesting and complex history and story behind it, or ever will again.