Considering History: Kamala Harris’s Heritage and the Legacies of Slavery and Sexual Violence

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s selection of Senator Kamala Harris to be his vice presidential running mate, a controversial Newsweek article raised questions of whether Harris, the daughter of two immigrants, would be eligible to serve in that role if elected. The article, authored by a right-wing law professor who had previously run against Harris for the position of California’s Attorney General, doesn’t hold legal water; Harris was born in Oakland and so was, from birth, a United States citizen, as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. But the article has reignited debates over that Constitutional concept of birthright citizenship, one that President Trump has at various times expressed a desire to do away with.

While Harris’s own citizenship status under that existing law is clear and indisputable (as Newsweek has subsequently admitted), there is another, more genuinely complex part of her heritage and family that has also received renewed attention since the VP announcement. In 2018, Harris’s father Donald, a Jamaican-American immigrant and retired Stanford University economics professor, wrote an article about his Jamaican ancestors in which he argued that he is descended on his father’s side from the infamous 19th century white slave owner Hamilton Brown, who ran one of the island’s largest plantations and was responsible for the importation and enslavement of hundreds of Africans.

Donald Harris’s claims about his relationship to Hamilton Brown have been used by conservative pundits like Dinesh D’Souza and others as a “gotcha” moment, as the basis for arguments that neither Harris nor her supporters can discuss the legacies of slavery and racism since she herself is descended from a white slave owner. But in truth that heritage, which is shared by a significant number of Americans of African descent, reflects one of the most essential and too-often forgotten histories of slavery and the sexual violence that accompanied it. And if we set aside political and partisan concerns, Harris’s story can help us understand those vital histories of slavery, sexual violence, race, and heritage, the legacies of which are certainly still with us in 21st century America.

One of the most consistent and central elements of chattel slavery, as it was practiced throughout the Americas, was the rape of enslaved women by male slave owners. It is difficult if not impossible to ascertain the percentage of enslaved women who were so violated (and thus of enslaved children who were the product of such acts), both because the practice was so ubiquitous and because it was for centuries under-narrated in histories of slavery. The latter trend has been challenged in recent years, as illustrated by historian Rachel Feinstein’s When Rape Was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery (2019) among other works.

Another recent trend that has made it more possible to grapple with these histories is the rise of ancestry studies and the corresponding use of DNA analysis to trace heritages. For example, the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., a pioneer in the use of such data to analyze individual, familial, and collective ancestries, estimates that “a whopping 35 percent of all African-American men descend from a white male ancestor who fathered a mulatto child sometime in the slavery era, most probably from rape or coerced sexuality.” And since that number reflects 21st century identities and all the other factors that have contributed to them, it likely only scratches the surface of how widespread these practices and their effects were in the era of slavery.

While many of those experiences are unfortunately lost to history, individual case studies can help us engage with the aftermath of sexual violence under slavery. As I highlighted in this July 4th column, the story of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings offers one particularly prominent such case study. After nearly two centuries of rumors and debate, both DNA analysis and the pioneering work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed have confirmed that Jefferson did rape and father at least one child (and almost certainly six or more children) with Hemings, one of the enslaved women on his Monticello plantation. Historians have only begun to uncover the complex stories of the descendants of those sexual assaults, enslaved young men and women who, despite their famous father and the promise of freedom that came with that status, still experienced some of the worst of antebellum American slavery and racism.

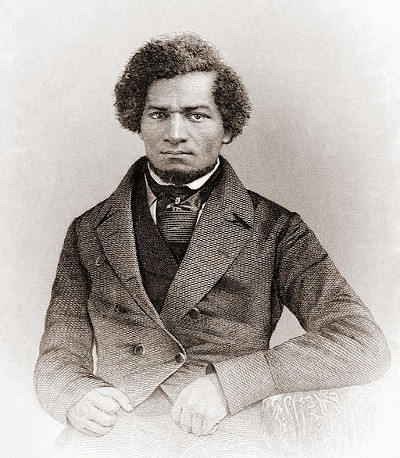

Another of the 19th century’s most famous Americans, Frederick Douglass, experienced life as the child of sexual assault under slavery. In the opening chapter of his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass notes his belief that his father, whom he never knew, was the white slave owner of the Maryland plantation onto which he was born. As usual with his autoethnographic works, Douglass uses this personal detail to illuminate social and historical meanings, noting for example that the law making the children of enslaved women themselves slaves “is done too obviously to administer to [slaveowners’] own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.” But Douglass also empathetically notes the potentially painful effects for all involved, from masters having to sell their own children to “one white son” having to “ply the gory lash to his [brother’s] naked back.”

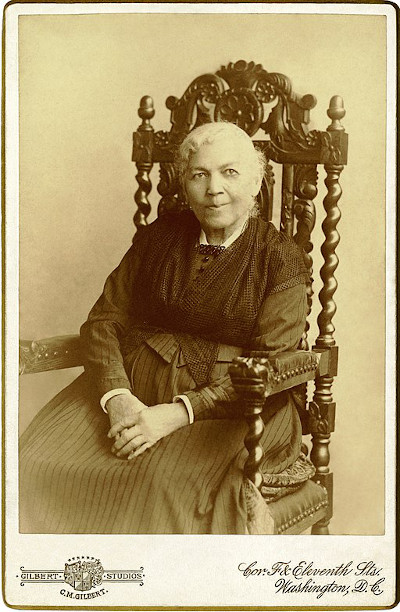

Douglass did not have the chance to know his mother well before her tragic death, so he was unable to write about her perspective. But another prominent personal narrative of slavery, Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), captures the experience of enslaved women under the constant threat of sexual violence. As Jacobs puts it in her chapter “The Trials of Girlhood,” “there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death; all these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men…She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master’s footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child.” And through her own constant battles with her despicable master Dr. Flint, Jacobs traces how “the influences of slavery had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me prematurely knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world.”

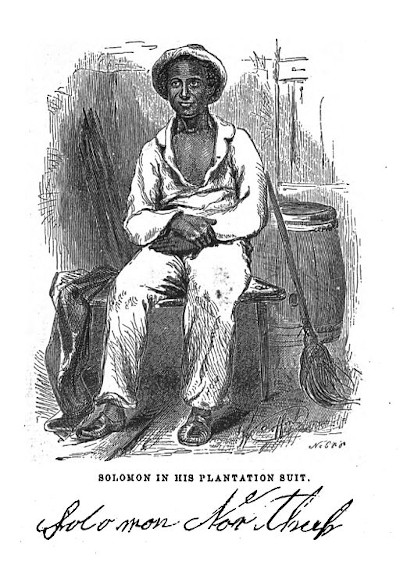

Individuals like Douglass and Jacobs managed to escape the horrors of slavery and publish their stories. But of course the vast majority of both enslaved women raped by their owners and the children of those rapes remained enslaved throughout their lives. We get a glimpse of such experiences in another personal narrative, Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853). At the final plantation to which Northrup is taken, he meets Patsey, an enslaved young woman whose beauty and strong will make her a singular focus of her owner Edwin Epps. If not enslaved, Northrup writes, Patsey “would have been chief among ten thousand of her people”; but on the Epps plantation, this impressive young woman becomes instead “the enslaved victim of lust and hate,” with “no comfort in her life.” Although the illegally kidnapped Northup is eventually rescued from the Epps plantation, he can do nothing for Patsey; a tragic reality captured in a culminating scene from the 2012 film adaptation of 12 Years, as Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) watches Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) recede as he rides away from the plantation.

No one can blame Northup in this moment, as there is nothing he can do for Patsey. But for far too long, both our laws and our collective memories likewise abandoned enslaved women like Patsey and their children to sexual violence and its effects. We cannot change the past, but—with heritages like Kamala Harris’s to help guide us—we can remember those histories and consider all that they mean for all Americans.

Featured image: Kim Wilson / Shutterstock

How to Become President without Being Elected

The early 1970s were some of the most tumultuous years in U.S. presidential politics. After the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew in October 1973, Speaker of the House Gerald Ford ascended to the role of vice president. When President Richard Nixon resigned in August 1974, Ford was sworn in as president. This is part of a chain of firsts; Ford is the only president to have not been elected to the position of president, or even vice president. He’s also the first person to become vice president after the invocation of the 25th Amendment, which provides for the filling of such a vacancy. As Ford’s vice presidency bid was confirmed by the Senate 45 years ago today, it’s the perfect time to look at both the circumstances surrounding this complicated switch, and what the 25th Amendment provides in the way of a mechanism to replace both the vice president and the president.

The 25th Amendment was one of the two most recent additions to the Constitution at the time of the Agnew resignation. (The 26th Amendment, which fixed the voting age at 18, was ratified in 1971.) The 25th Amendment was submitted to the states in 1965 and ratified in 1967. It’s a four-section document with fairly direct language. Section 1 is one simple sentence: “In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President.” Likewise, Section 2 is equally simple: “Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.”

The remainder of the amendment requires a little more explanation. Section 3 provides for the vice president to step in as acting president if the president submits a written declaration to the “President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives” that states that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” The president would have to notify the same parties when able to take those responsibilities back. This portion has been invoked three times: in 1985, 2002, and 2007. In all three instances, the president (Ronald Reagan in 1985; George W. Bush in the other two cases) underwent a colonoscopy and transferred power for a matter of hours. It might also sound familiar if you’re a fan of The West Wing; the issue came into play during the story arc involving the kidnapping of Zoey Bartlet (though power went to the speaker of the house as the vice president had resigned). If you’re wondering about what happened when Reagan was shot in 1981, that’s covered by Section 4.

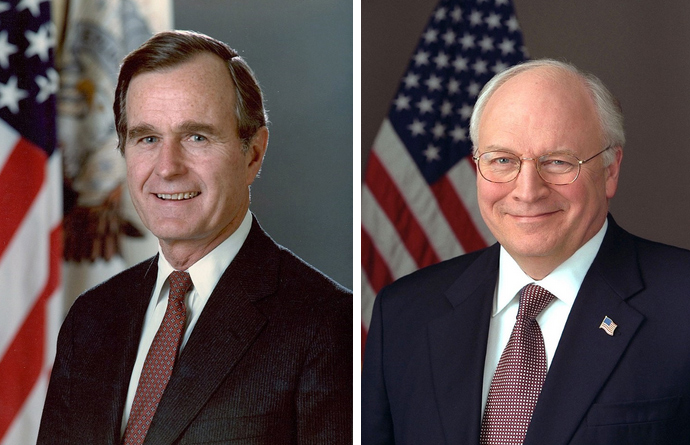

Section 4 holds a lot of potential for conflict, but it’s also a safety valve of sorts. The vice president, with a plurality of the cabinet and/or Congress, may declare to the president pro tempore of the Senate and the speaker of the House of Representatives that president is unfit, allowing the vice president to become acting president. The second paragraph covers what would happen if the president disagrees; at that point, a two-thirds vote of Congress would be necessary to keep the vice president installed as acting president. When Reagan was shot, he was obviously not in a position to invoke Section 3. Vice President George H.W. Bush was on a flight at the time of the shooting, and not able to invoke Section 4. President Reagan was out of surgery by the time that the plane landed; therefore, no invocation of Section 4 occurred.

However, that doesn’t mean that other discussions of Section 4 haven’t taken place. Reagan’s third chief of staff, Howard Baker, had been approached by worried staff members regarding Regan’s competence after Baker became chief of staff in 1987. President Reagan’s battle with Alzheimer’s disease was not publicly disclosed until 1994, five years after he left office, and there’s no hard public evidence that he was dealing with the disease while president. Critics of Donald Trump have also called for invoking the 25th Amendment, with a number of outlets also reporting on talks among his staff or offering speculation on the topic when the president says something outrageous (which is, admittedly, common).

Spiro Agnew resigns.

But back in 1973, the use of the amendment wasn’t a tool for partisan threats or West Wing handwringing; it was a rulebook for averting a Constitutional crisis. Agnew resigned after being investigated for tax fraud and corruption. On October 9 of that year, Agnew informed Nixon of this plans to resign; the following day, he pled no contest on a charge of tax evasion and submitted his formal letter of resignation. Nixon invoked Section 2 and nominated Ford for vice president on October 12. The Senate voted for confirmation on November 27, with the House of Representatives following suit on December 6, 1973; Ford was sworn in just one hour later. The great irony, of course, is that Nixon would resign after the Watergate scandal in 1974, leading to Ford’s ascension to office. Ford lost the 1976 presidential race to Jimmy Carter and would become the only U.S. president and vice president to serve without being elected as such.

Gerald Ford sworn in as vice president.

Regardless of where the winds of political and historical fate send the presidency today, these situations underscore what a durable instrument that the United State Constitution is. Benjamin Franklin, who holds the distinction of having signed the Declaration of Independence, the 1781 Treaty of Paris, and the U.S. Constitution, urged his fellows in the Constitutional Convention to sign the document; as transcribed by James Madison, Franklin said, “I hope therefore that for our own Sakes, as a Part of the People, and for the sake of our Posterity, we shall act heartily and unanimously in recommending this Constitution, wherever our Influence may extend, and turn our future Thoughts and Endeavours to the Means of having it well administered.“ Franklin would no doubt be encouraged that it’s worked pretty well so far.

E Pluribus Trivia

Nine of our 47 vice presidents inherited the presidency—eight from a president’s death and one because President Richard Nixon quit. Seven vice presidents died in office. Two vice presidents resigned: John C. Calhoun to go to the Senate, and Spiro Agnew to go into hiding.

George Clinton was the first of seven vice presidents to die in office (1812). The second was Elbridge Gerry (1814), who gave his name to the notorious and ongoing practice of gerrymandering—creating misshapen voting districts to ensure your party’s victory. Both served under James Madison, president from 1809 to 1817.

Richard Mentor Johnson, V.P. under Martin Van Buren (1837–1841), rose to political prominence partly on his reputation for having personally killed Shawnee Chief Tecumseh in the war of 1812. His reputation came undone in subsequent years when word got out that his common-law wife, with whom he had two daughters, was the light-skinned slave Julia Chinn. She died in the cholera epidemic of 1833, and her existence was conveniently swept under the rug during his period serving as V.P. For the record, Johnson educated and deeded property to his two daughters.

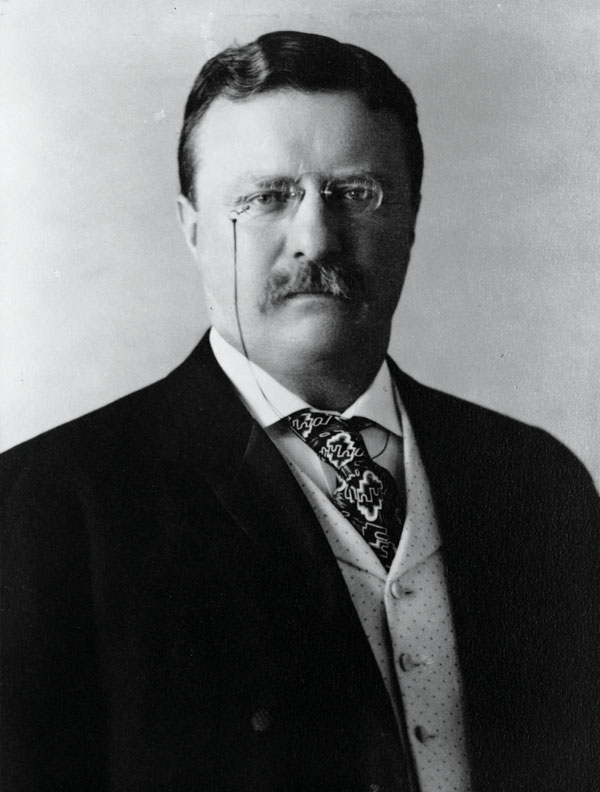

Theodore Roosevelt found the job of presiding over the Senate so tedious that he often slept at his desk. He famously said of his senatorial charges, “When they call the roll in the Senate, the Senators do not know whether to answer ‘Present’ or ‘Guilty.'”

Charles G. Dawes is the sole vice president to write a hit song. His 1912 “Melody in A Major” later had words added and became “It’s All in the Game.” Tommy Edwards took the song to number one in 1958, seven years after Dawes’s death.

Not until Alben Barkley in 1949 was the vice president called “The Veep,” a term coined by a young Barkley relative. It was noted by the Oxford English Dictionary in 1949 and has passed into common usage.

The Worst 10 1/2* Vice Presidents

What do Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Hannibal Hamlin, and Millard Fillmore have in common? All are former vice presidents of the United States. Two are on Mount Rushmore; two are not.

What do Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Hannibal Hamlin, and Millard Fillmore have in common? All are former vice presidents of the United States. Two are on Mount Rushmore; two are not.

Forty-seven men have occupied the office of vice president, and while they were in there, they did little other than serve as presiding officer of the Senate, their only constitutional mandate.

Vice presidents were chosen more for perceived vote-getting abilities than because of genuine credentials as public servants—which many had. Even so, an aura of veiled weirdness has hovered over the office for more than two centuries.

In 1788, the U.S. held its first presidential election under a flawed system: The man with the most electoral votes got to be president, and the man finishing second became vice president. President John Adams, elected following Washington in 1796, and Vice President Thomas Jefferson detested each other. Imagine George W. Bush with Al Gore as vice president or an Obama-Romney administration, and you’ll understand.

In 1800, Jefferson and Adams faced off—the first time two former vice presidents mutually sought the presidency. But Adams finished third while Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied with 73 votes each. Burr had agreed in advance to serve as Jefferson’s vice president, and that’s how things ultimately worked out.

Jefferson’s near-disaster led to the passage of the 12th Amendment, which required electors to cast separate votes for the two offices. This spared us, up to a point, acrimony between the two top office holders. Since the first vice president was elected in 1788, a motley of murderers, traitors, bribe takers, and outright crooks have paraded through the vice presidency. What’s more, during the 224 years between 1788 and 2012, the office has stood vacant on 18 occasions for a total of almost 38 years.

The nation survived not only those 18 vacancies but also the 10 and one-half vice presidents we examine below.

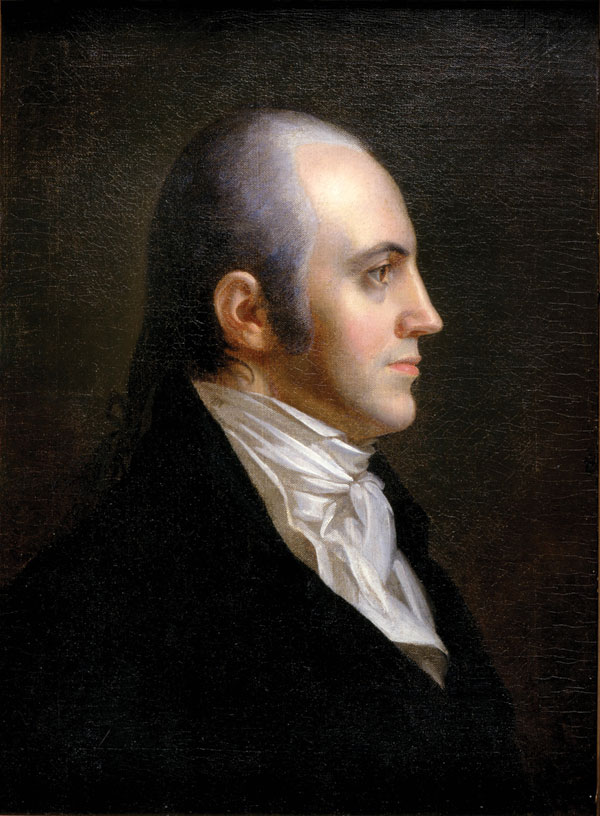

Aaron Burr

(1801-1805)

Our third vice president, Aaron Burr of New York, set the tone of lunacy that so often defines the office. Burr killed Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in an illegal duel and got himself charged with murder in both New York and New Jersey. After leaving office, shady land deals in the western wilderness got him charged with treason. He was never convicted of either crime.

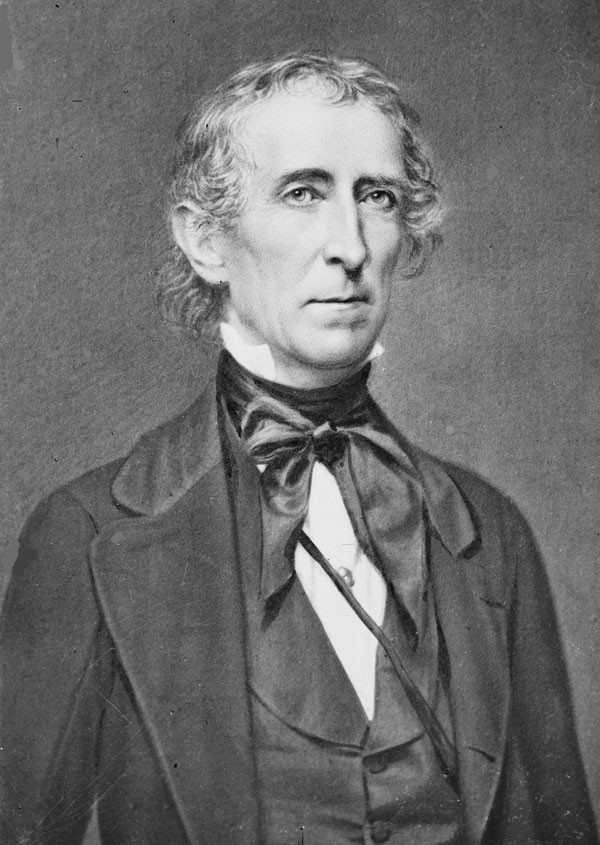

John Tyler*

(1841)

How do you get one-half of a vice president? John Tyler of Virginia did it this way. He was the “too” of the 1840 campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” The “Tippecanoe” half of the ticket was William Henry Harrison who spoke for three hours at his rainy inauguration, caught pneumonia, and died 31 days later, making Tyler our shortest-serving vice president.

Incredibly, though the Constitution provided for a vice president, it did not state expressly that the vice president would assume the office of president following a chief executive’s death. A quick-acting Congress rectified this … in 1967.

Before even being elevated to the presidency, Tyler signaled his lack of interest in his elected position. In fact, immediately after Harrison’s inauguration, Tyler left Washington and didn’t return until he was summoned at the president’s death. On his return, Tyler resisted congressional attempts to name him “temporary” or “acting” president and served almost a full term as a no-asterisk president. In that post, however, he was unremarkable and historians have called him weak. He so alienated his party that he was denied its nomination for the election of 1844.

Millard Fillmore

(1849-1850)

Millard Fillmore, who became chief executive in 1850 when President Zachary Taylor died of natural causes, was the first vice president of urban legend, though not until 43 years after his death. In a 1917 column, humorist H.L. Mencken wrote that Fillmore had introduced the first bathtub into the White House. This was an outright hoax, but people believed it, then and now.

Mencken came clean in 1949, but the story remains alive. As a part of “Fillmore Days” in Moravia, New York—near Fillmore’s birthplace—wheeled bathtubs race through the city’s streets.

William Rufus King

(1853)

King served only slightly longer than Tyler. He was elected with Franklin Pierce in 1852 and served 46 days before expiring. King is best remembered as our only bachelor vice president and as the longtime roommate of James Buchanan, who in 1856 became the only bachelor elected president.

The Buchanan-King duo was known around Washington as the “Siamese twins,” and President Andrew Jackson referred to them as “Aunt Fancy and Miss Nancy.” King’s brief tenure, not his private life, places him on our list.

A footnote to the bachelors: Buchanan’s vice president, John C. Breckenridge, finished his one term and left town in 1861 to join the Confederates. He was one of two vice presidential turncoats, the other being Tyler, who served as a Confederate legislator.

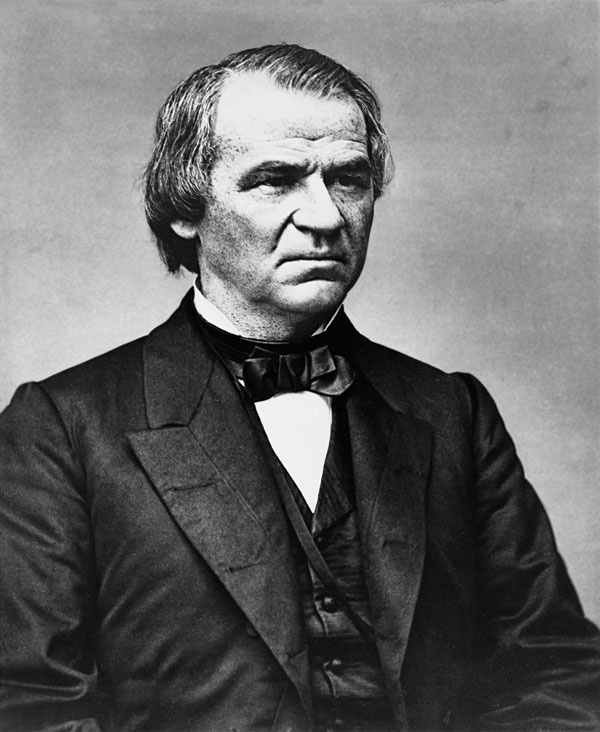

Andrew Johnson

(1865)

Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat and a tailor by trade, ran with Abraham Lincoln in 1864 on something called the National Union ticket. He got things rolling by showing up apparently inebriated for his inauguration. (Honest Abe later said, “Andy ain’t a drunkard”—possibly the only time a president publicly defended a vice president.)

When Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, Johnson took office and found himself at loggerheads with the Republican administration. A former slave owner, Johnson displayed few concerns for the rights of recently freed slaves and was ultimately impeached by the House and put on trial in the Senate.

Johnson avoided expulsion by a single vote and in 1868 joined the growing parade of vice presidents who gained the presidency but were denied their party’s nomination.

Schuyler Colfax

(1869-1873)

Selected to run with Civil War hero Ulysses Grant in 1868, Colfax had previously served as Speaker of the House of Representatives. Grant, 46, and Colfax, 45, formed the youngest team ever to run for the two offices until Bill Clinton and Al Gore ran in 1992.

A native New Yorker and friend of editor Horace Greeley, Colfax took Greeley’s advice and moved west to South Bend, Indiana. He served as a U.S. Representative from his adopted state. During Grant’s first term, Colfax’s involvement in the Crédit Mobilier of America railroad scandal transpired. (Ironically, Colfax would later drop dead on a railroad station platform after walking three-quarters of a mile in subfreezing Minnesota weather.) He was not nominated for a second term.

He was the first of two vice presidents to preside over both houses of Congress, the other being John Nance Garner. Appropriately enough for a vice president, he was a member of the International Order of Odd Fellows.

Colfax is buried in South Bend, one of four vice presidents buried in Indiana. Keeping their distance, the others are buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

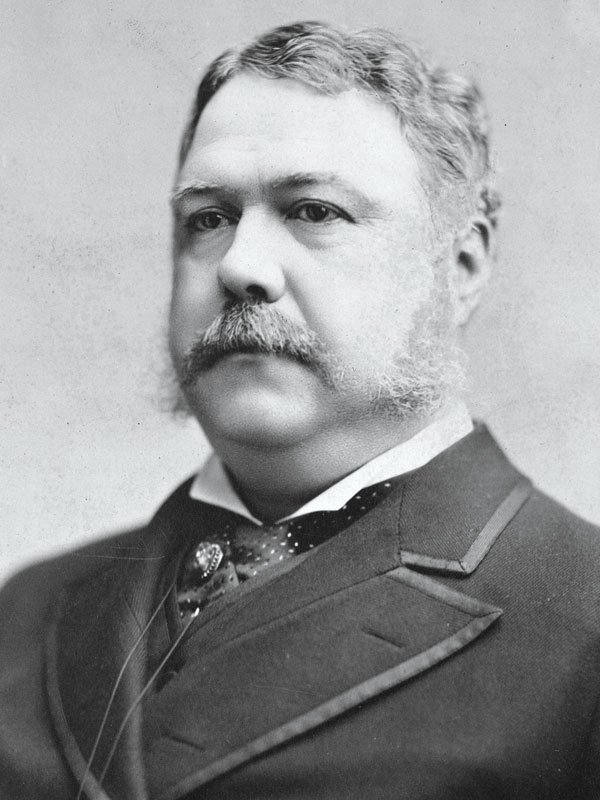

Chester Arthur

(1881-1885)

Utopian religious nut Charles J. Guiteau shot President James Garfield on July 2, 1881, and announced “Arthur is president now!” He was wrong. It took Garfield until September 19 to die.

Arthur came to the vice presidency in a cloud of controversy. He’d been removed from his post as collector of the port of New York 10 years earlier amid charges of corruption. But once in the White House, Arthur is credited by most historians as a reformer. None other than Mark Twain praised his presidency. But the high-living, overweight gourmand would not serve a second term. After learning he was dying of kidney disease, Arthur made only a half-hearted attempt to secure his party’s nomination, and he left office in 1885.

Charles G. Dawes

(1925-1929)

Dawes could not get along with his boss Calvin Coolidge and refused even to attend cabinet meetings. The first time he addressed the Senate, he made a speech denouncing the way it conducted business. Later, he napped through a decisive vote, which resulted in a Coolidge appointee losing his job. Dawes is one of two V.P.s to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. (The other was Teddy Roosevelt.) Dawes received his accolade in 1925 for the Dawes Plan, aimed at restoring German economic equilibrium after World War I. It ultimately did not work, but he got to keep the prize.

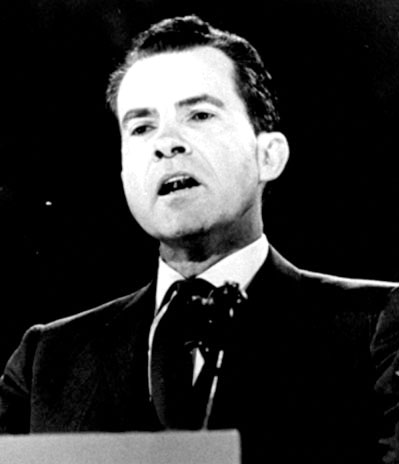

Richard Nixon

(1953-1961)

Richard Nixon, elected with Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, gave generously to the dusty storehouse of vice presidential trivia. Asked what Nixon’s principal contribution to foreign affairs was, Eisenhower replied, “If you give me a week, I might think of one.”

To be fair, some historians would counter that Nixon did a good job presiding over Eisenhower’s cabinet for six weeks while the president recovered from a heart attack. (See “Richard Nixon—A Great President!” The Contrarian View, Nov/Dec 2012.) Nixon was the only vice president to be elected president after leaving office and suffering through two opposition presidents: Kennedy and Johnson.

When Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned following a bribery scandal in 1973, Nixon appointed Gerald Ford of Michigan to the post. Then, when Nixon himself resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandals, Ford became president and appointed Nelson Rockefeller vice president.

The presidential nomination of a vice president—who went missing for whatever reason—was not possible until 1967 when the 25th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified.

Spiro Agnew

(1969-1973)

Spiro Agnew oozed onto the political scene with Nixon in 1968. A former governor of Maryland, Agnew was the first vice president to serve his master as an attack dog, and relished uttering such phrases as “nattering nabobs of negativism” to define the Washington press corps. As we have seen, the press had the last laugh.

Dan Quayle

(1989-1993)

Dan Quayle, the fifth vice president elected from Indiana, first got himself roasted in the 1988 vice presidential debate by Democrat Lloyd Bentsen: “You’re no Jack Kennedy.” He then went on to publicly misspell “potato” as “potatoe.” Investigation later revealed that he’d been given a flash card containing the errant spelling, but the damage was done.

Quayle, a sitting U.S. Senator, took office with George H.W. Bush and was somehow invited to run for a second term. In Quayle’s hometown of Huntington, Indiana, stands the Quayle Vice Presidential Learning Center. According to Roadside America, visitors can view such exhibits as Dan Quayle’s grammar-school report cards (Bs and As, thank you very much) and one of Millard Fillmore’s hats.

Were there any good vice presidents? Beginning with Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, there were a few. And remember that, under the original electoral system, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were vice presidents.

Teddy Roosevelt won both the Republican nomination for president in 1904 and the subsequent election. In 1912, he ran unsuccessfully for president with his ill-starred Bull Moose Party (see “100 Years Ago—A Chaotic Presidential Election”). By then, however, he had won the Nobel Peace Prize, served as New York City’s police commissioner, Governor of New York, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and established himself as a dedicated conservationist and successful reformer.

John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner from Uvalde, Texas, served as vice president for two terms under Franklin Roosevelt. He is most famous for his definitions of the office he occupied, but he was also a former Speaker of the House and a power in Democratic politics. He might well have become president had FDR not run for an unprecedented third term.

Harry Truman, elected vice president for FDR’s even more unprecedented fourth term, assumed the presidency on April 12, 1945, when FDR died less than three months after the inauguration. Truman was nominated for president in 1948 and elected, but his contribution to the vice presidency went far deeper than personal success.

Truman took office with a minimum of preparation—FDR had essentially ignored him—and found his plate filled with such items as World War II, the atomic bomb, peace in Europe, and Soviet expansionism. He vowed that no vice president should ever again be so blindsided, and he put his own vice president, Kentucky’s popular Alben Barkley, on the National Security Council and otherwise involved him in government.

From Truman forward, some but not all vice presidents ran as men (and one woman, Geraldine Ferraro) considered capable of occupying the presidency. Is it our bad luck or our good fortune that only one vice president, George H.W. Bush (whose linguistic contribution was “Voodoo Economics”), has made it to the presidency in the last 44 years?