The Female War Correspondent Who Sneaked into D-Day

At the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis in 1916, Martha Gellhorn stood in a protest called the Golden Lane. She was only 8 years old, but her mother, a suffragist, had organized 7,000 women clad in yellow sashes and parasols to line Locust Street — the route delegates would take to the St. Louis Coliseum. Toward the end of the line, seven women in white represented states that endorsed women’s suffrage, and many others in gray and black stood for states unwilling to budge. Gellhorn, in a white dress, represented a future woman voter.

This initial act of defiance was only the beginning for Gellhorn. The young girl in white would go on to lead a daring and adventurous career. Throughout her life, as a war correspondent and author, she witnessed some of the most influential occurrences of the 20th century, from the Great Depression to D-Day to the U.S. invasion of Panama. From her feminist start in St. Louis, Gellhorn travelled the world and became one of the most important journalists of the century. And she did it all without permission.

Like many writers and artists of the time, Gellhorn moved to Paris in 1930. After dropping out of Bryn Mawr College and working briefly for New Republic, the young reporter was itching to become a foreign correspondent. Gellhorn landed a job with the United Press, but was fired after reporting sexual harassment by a man connected with the agency. She spent many years travelling Europe, writing for papers in Paris and St. Louis, and even covering fashion for Vogue. While noticing the rise of fascism in Germany, Gellhorn remained a pacifist in mostly leftist circles. She decided to return to the States in 1934 because, as she said, the poverty she witnessed in Europe was rampant in her own country.

Gellhorn soon earned a spot as an investigator in Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration, travelling around the country and giving firsthand reports of the grim living and working conditions. She trudged around North Carolina in secondhand Parisian couture, interviewing five families a day and growing ever more troubled about the widespread destitution. Gellhorn called on Roosevelt to do more about a syphilis epidemic and lack of birth control. Her boldness gained her the ear of Eleanor Roosevelt, who became a lifelong friend.

While on assignment in Idaho, Gellhorn convinced a group of workers to break the windows of the FERA office to draw attention to their crooked boss. Although their stunt worked, she was fired from FERA: an “honorable discharge” for being “a dangerous Communist,” she wrote wryly to her parents. The Roosevelts then invited Gellhorn to live at the White House, and she spent her evenings there assisting Eleanor Roosevelt with correspondence and the first lady’s “My Day” column in Women’s Home Companion.

She soon moved on, however, feeling a need to publish her experiences with impoverished America. “The material was fresh, dramatic, and intensely present in her mind,” Caroline Moorehead writes in her Gellhorn biography. “It was a question of distilling it. She had been haunted by what she had seen; now, she had to haunt others.” The resulting book, The Trouble I’ve Seen, earned Gellhorn acclaim from reviewers all over the world for its frank writing style and urgently important stories.

Around the same time, she began a relationship with Ernest Hemingway after meeting the acclaimed novelist at a bar called Sloppy Joe’s in Key West. They hopped on a boat to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War, and Gellhorn found her beat as a war reporter. She began to publish with Collier’s and the New Yorker on the view from Madrid. Gellhorn and Hemingway travelled to China for the Second Sino-Japanese War, then back to Europe to document World War II from London. They married in 1940.

On June 6, 1944, Gellhorn did not receive official clearance to attend the Allied invasion of Normandy (as Hemingway had), but she sneaked onto a hospital ship and locked herself in a bathroom until it began making its way across the channel. They arrived on Omaha Beach, and Gellhorn became the first female reporter on the scene, disguised as a stretcher-bearer. She arrived in Normandy before Hemingway, wading to the beach to collect casualties and assist medical teams. In her report for Collier’s she observed:

Everyone was violently busy on that crowded, dangerous shore. The pebbles were the size of apples and feet deep, and we stumbled up a road that a huge road shovel was scooping out. We walked with the utmost care between the narrowly placed white tape lines that marked the mine-cleared path, and headed for a tent marked with a red cross… Everyone agreed that the beach was a stinker, and that it would be a great pleasure to get the hell out of here sometime.

Gellhorn followed the war eagerly, estranging her relationship with a famous husband who preferred to have her at home. She covered the liberation of Dachau and Paris and wrote for this magazine about the 82nd Airborne Division, utilizing her extensive knowledge of the war’s bigger picture to give context to everyday combat scenes.

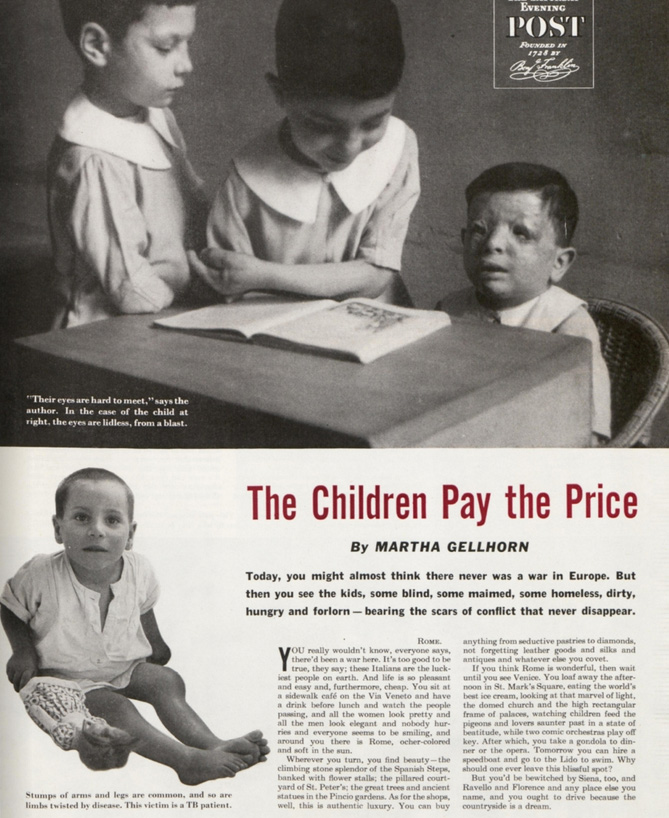

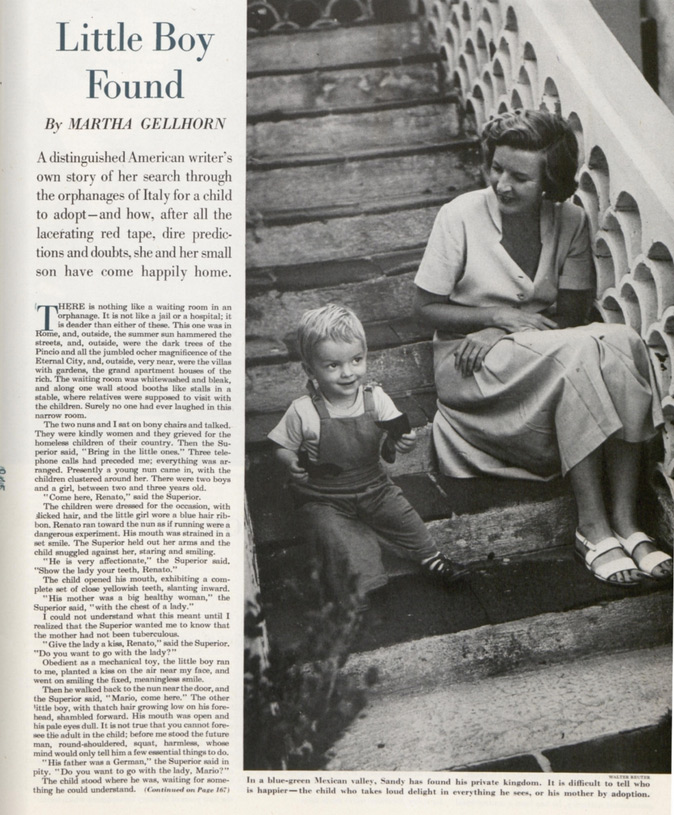

After the war, Gellhorn divorced Hemingway and lived for a time in Cuernavaca, Mexico. She continued to write for The Saturday Evening Post, first to explore the toll of the war on the street children of Rome, then to document her adoption of an Italian orphan:

I knew those children in the war. I saw them scraping an existence for themselves in the rubble of Naples; I saw them brought in, bleeding and wild, to battalion aid stations because they’d walked on mines like any soldier; I saw them dumped into trucks and moved, they didn’t know where. I thought them the bravest people possible, and beautiful and quick and cheerful in the center of hell, where they lived… They ought to declare war on grownups, I thought furiously, who killed their childhood.

Her adopted son, George “Sandy” Alexander, required letters from several ambassadors and the Roosevelts to leave with Gellhorn out of Florence.

Gellhorn’s years as a war correspondent weren’t behind her. However, she lost favor with many American publications after declaring herself firmly against the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson. The Guardian agreed to buy six articles from Gellhorn in 1966 when she explained her intention to carry on her style of covering everyday life during conflict: “I want to write about the Vietnamese, the civilians, whom everyone has forgotten are people. I want to try, humbly, to give them faces so we know who we are destroying.” She urged American journalists to cover Vietnam fairly instead of catering to military interests.

Gellhorn covered Nicaraguan contras, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and, in 1989, the U.S. invasion of Panama. As a lifelong pacifist, she criticized U.S. foreign policies increasingly after World War II, dubbing the U.S. a “colonial power.” Her prose aimed to expose the detriments of war, documenting intimate details of ordinary citizens. She claimed to merely write what she would see instead of attempting to offer perspectives for both sides of a conflict.

At 89 years old, blind and suffering from ovarian cancer, Gellhorn swallowed a cyanide pill in her London flat. Her New York Times obituary described her as “a cocky, raspy-voiced maverick who saw herself as a champion of ordinary people trapped in conflicts created by the rich and powerful.”

Above all, Gellhorn refused to be remembered as Hemingway’s wife. After all, it was the least interesting fact about her. “I was a writer before I met him, and I have been a writer for 45 years since,” she wrote. “Why should I be a footnote to someone else’s life?”

Correction: October 25, 2020

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Gellhorn was fired from United Press “after reporting sexual harassment by a coworker.” According to Caroline Moorehead’s biography of Gellhorn, “a visiting South American tycoon, in some way linked to the news agency, made a pass at her in a taxi.”

Vietnam Vets: ‘Why We Chose to Serve’

It’s not unusual for vets in uniform to be stopped by strangers and told how much their service is valued, especially around Veterans Day. But Americans weren’t always grateful to the men and women who served in the military. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, some treated Vietnam veterans with indifference or even blatant hostility.

The country had been generally supportive of the Vietnam War in its early days. An October 1965 Post survey found 65 percent of Americans ready to extend the Vietnam War another four to five years. And 59 percent were willing to escalate it, “even if it means bombing Hanoi and Red China.” But enthusiasm faded as the country learned the harsh realities of the fighting. In time, some Americans extended their resentment of the war to the men who were fighting it. The war became an uncomfortable fact, and its veterans were given scant recognition for their service.

Below, five Vietnam veterans share thoughts about service to country, the public’s reaction to their service, and how it shaped their thoughts on war today.

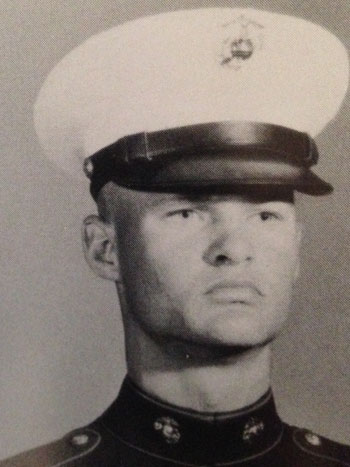

Charles Boland, Corporal, USMC

Making a choice: “I knew the chances were quite high that I’d be drafted, and I always wanted to be a Marine. … There is no other service with its history of the esprit de corps. When you enlist in the Marines, you’re changed forever.”

Public reactions: “I was wounded, evacuated, and sent home. … I remember being confronted by a woman. She asked me how I’d been hurt. When I told her I’d been wounded in Vietnam, she said, ‘I wish you’d been killed.’ Until then, I hadn’t been confronted by hatred.

“People walk up to you now and say, ‘Thanks for your service.’ But some vets get mad when they hear this. They tell me they get the feeling what’s really being said is ‘thank you for serving so I didn’t have to.’”

Serving the country: “Just paying your taxes is like buying a substitute to take your place in the Civil War. … I think there should a greater sense of service to country … in the Peace Corps, in communities, assisting other people, volunteering at VA hospitals to free up the staff, not just in the military.”

Reflecting on the war: “Too many people are willing to go to war at the drop of the hat. They’re not really willing to look at what’s going on.”

Dave Beyerlein, Infantry Sergeant, USMC

Making a choice: “I joined in March of 1966 with a buddy in Portland. The Marines grew me up and gave me respect for authority.”

Public reactions: “There was no respect for time spent and sacrifices made. We caught a lot of crap from people. At least one person called me a baby killer.

“It took decades for America’s thinking to come around so people could recognize that we [veterans] were just slobs who got caught in the war. Problem is, it took a lifetime to for that to happen.”

Serving the country: “I believe everyone should spend two years in service to our country. If you’re just along for a free ride, you don’t understand what you’re getting for free. It doesn’t have to be the military; it can be any service. But it gives you ownership. It will give you a different perspective and you’ll value your citizenship more.”

Reflecting on the war: “I’m so antiwar now it’s crazy. The war we were in was totally worthless. It was what, 58,000 dead? And now Vietnam’s one of our trading partners, and they’re still communist.”

Randolph Schiffer, First Lieutenant, USMC, Commander, USN Reserves

Making a choice: “For young men in America in the 1960s, the Vietnam War was the central issue. … I wanted to face this issue squarely. … I [joined the Marines] to make a statement to myself about duty, honor, and loyalty to country.”

Public reactions: “I was accepted at three top-tier medical schools before I went, but when I returned two of those three refused to reaccept me, as did seven others to which I applied. The sentiment in the medical schools was exemplified by the admissions committee feedback given to me in person by Harvard. ‘We’re not taking you because you’re a Vietnam veteran,’ they said. When I asked what specifically it was about the veteran part, they said, ‘We just don’t think a Vietnam veteran could do the work at Harvard Medical School.’

“There has been a complete inversion in Americans’ attitude toward veterans. People who return from the Mideast war can’t walk into a room without hearing ‘thanks for your service.’ I didn’t hear that when I came back in 1972.

“I believe what we’re seeing here is the national guilt and shame about the way they treated people like me in the 1960s. … Now I get admiration for my service, but it was a long road to getting it.”

Reflecting on the war: “Eisenhower said the most powerful military force is an aroused democracy. We don’t have that now. … The wealthy, powerful, and white, in many cases, are saying ‘I don’t want to serve in military.’ We have a professional military. It’s smaller and better paid, but not diverse enough to be representative of the country.”

Ted Decker, Corporal E4, USMC

Making a choice: “I’d decided that, if I was going to serve, I’d serve as a Marine … all the while knowing there was a good chance I was going to Vietnam. … I take great pride in it [my service]. But military life is not for everyone. We, as a nation, have to respect people who do that. It’s a hard life.”

Public reactions: “Back then, vets were looked on with disdain. Vets today are treated with more respect. I think we paid for it.”

Serving the country: “I had a chance to see different cultures, and I realized that ours is a great country. I didn’t appreciate the simple things until I had to do without them. … I think every young man or woman should spend at least a year in service, in some form, whether in the Peace Corps or some such organization.”

Reflecting on the war: “After the death and atrocities I’ve seen, I wonder why God spared me. I came close to death so many times. But when I look at my son and three grandsons, I know.

“I don’t think we should ever forget Vietnam. What that war did was make us a nation that’s afraid to act until it’s too late. We keep waiting and hoping things will get better.”

Andres Vaart, Captain, USMC

Making a choice: “I was an immigrant [from Estonia]. My mother and I were fortunate enough to get to the U.S. in 1950. I felt strongly that military service was the right thing, knowing what it was like to be occupied by Soviet Union. … I was interested in joining the Marines. I knew we’d be going to Vietnam, but I would be going into service to fight communism. It didn’t matter where.”

Serving the country: “To me, the idea of universal service to the nation is a very reasonable one, whether in the military or somewhere else.”

Reflecting on the war: “In those days, there was one big enemy. We got used to the big enemy we had to unify to oppose. Now I wonder if we got into that habit of thinking: We now leap to the idea of that one big thing, whether it’s the Chinese, Islam, or general terrorism.

“I sometimes wonder about the most powerful nation on earth being the most fearful nation. I think we should respond to challenges with something other than fear — rather a sense of acceptance and some confidence we know how to deal with problems.”