At the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis in 1916, Martha Gellhorn stood in a protest called the Golden Lane. She was only 8 years old, but her mother, a suffragist, had organized 7,000 women clad in yellow sashes and parasols to line Locust Street — the route delegates would take to the St. Louis Coliseum. Toward the end of the line, seven women in white represented states that endorsed women’s suffrage, and many others in gray and black stood for states unwilling to budge. Gellhorn, in a white dress, represented a future woman voter.

This initial act of defiance was only the beginning for Gellhorn. The young girl in white would go on to lead a daring and adventurous career. Throughout her life, as a war correspondent and author, she witnessed some of the most influential occurrences of the 20th century, from the Great Depression to D-Day to the U.S. invasion of Panama. From her feminist start in St. Louis, Gellhorn travelled the world and became one of the most important journalists of the century. And she did it all without permission.

Like many writers and artists of the time, Gellhorn moved to Paris in 1930. After dropping out of Bryn Mawr College and working briefly for New Republic, the young reporter was itching to become a foreign correspondent. Gellhorn landed a job with the United Press, but was fired after reporting sexual harassment by a man connected with the agency. She spent many years travelling Europe, writing for papers in Paris and St. Louis, and even covering fashion for Vogue. While noticing the rise of fascism in Germany, Gellhorn remained a pacifist in mostly leftist circles. She decided to return to the States in 1934 because, as she said, the poverty she witnessed in Europe was rampant in her own country.

Gellhorn soon earned a spot as an investigator in Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration, travelling around the country and giving firsthand reports of the grim living and working conditions. She trudged around North Carolina in secondhand Parisian couture, interviewing five families a day and growing ever more troubled about the widespread destitution. Gellhorn called on Roosevelt to do more about a syphilis epidemic and lack of birth control. Her boldness gained her the ear of Eleanor Roosevelt, who became a lifelong friend.

While on assignment in Idaho, Gellhorn convinced a group of workers to break the windows of the FERA office to draw attention to their crooked boss. Although their stunt worked, she was fired from FERA: an “honorable discharge” for being “a dangerous Communist,” she wrote wryly to her parents. The Roosevelts then invited Gellhorn to live at the White House, and she spent her evenings there assisting Eleanor Roosevelt with correspondence and the first lady’s “My Day” column in Women’s Home Companion.

She soon moved on, however, feeling a need to publish her experiences with impoverished America. “The material was fresh, dramatic, and intensely present in her mind,” Caroline Moorehead writes in her Gellhorn biography. “It was a question of distilling it. She had been haunted by what she had seen; now, she had to haunt others.” The resulting book, The Trouble I’ve Seen, earned Gellhorn acclaim from reviewers all over the world for its frank writing style and urgently important stories.

Around the same time, she began a relationship with Ernest Hemingway after meeting the acclaimed novelist at a bar called Sloppy Joe’s in Key West. They hopped on a boat to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War, and Gellhorn found her beat as a war reporter. She began to publish with Collier’s and the New Yorker on the view from Madrid. Gellhorn and Hemingway travelled to China for the Second Sino-Japanese War, then back to Europe to document World War II from London. They married in 1940.

On June 6, 1944, Gellhorn did not receive official clearance to attend the Allied invasion of Normandy (as Hemingway had), but she sneaked onto a hospital ship and locked herself in a bathroom until it began making its way across the channel. They arrived on Omaha Beach, and Gellhorn became the first female reporter on the scene, disguised as a stretcher-bearer. She arrived in Normandy before Hemingway, wading to the beach to collect casualties and assist medical teams. In her report for Collier’s she observed:

Everyone was violently busy on that crowded, dangerous shore. The pebbles were the size of apples and feet deep, and we stumbled up a road that a huge road shovel was scooping out. We walked with the utmost care between the narrowly placed white tape lines that marked the mine-cleared path, and headed for a tent marked with a red cross… Everyone agreed that the beach was a stinker, and that it would be a great pleasure to get the hell out of here sometime.

Gellhorn followed the war eagerly, estranging her relationship with a famous husband who preferred to have her at home. She covered the liberation of Dachau and Paris and wrote for this magazine about the 82nd Airborne Division, utilizing her extensive knowledge of the war’s bigger picture to give context to everyday combat scenes.

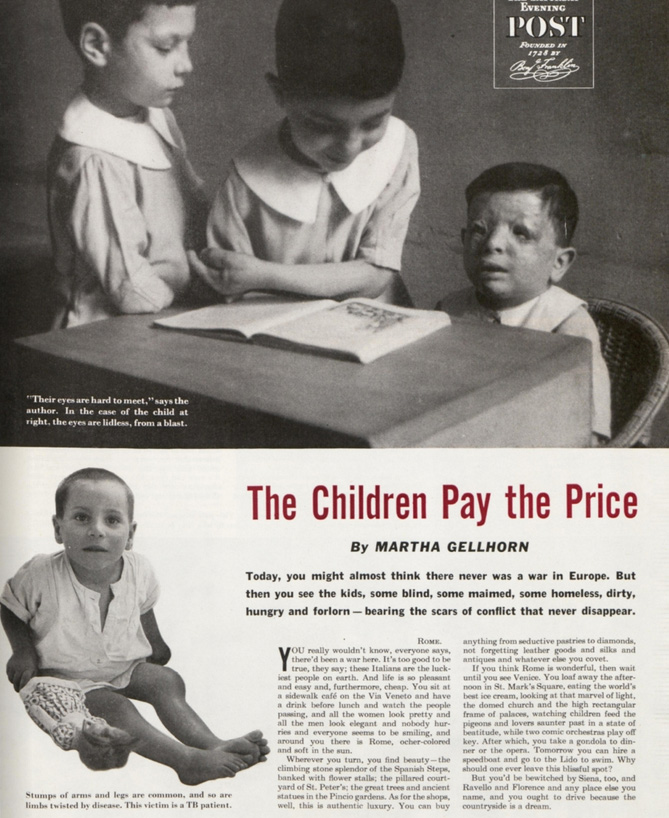

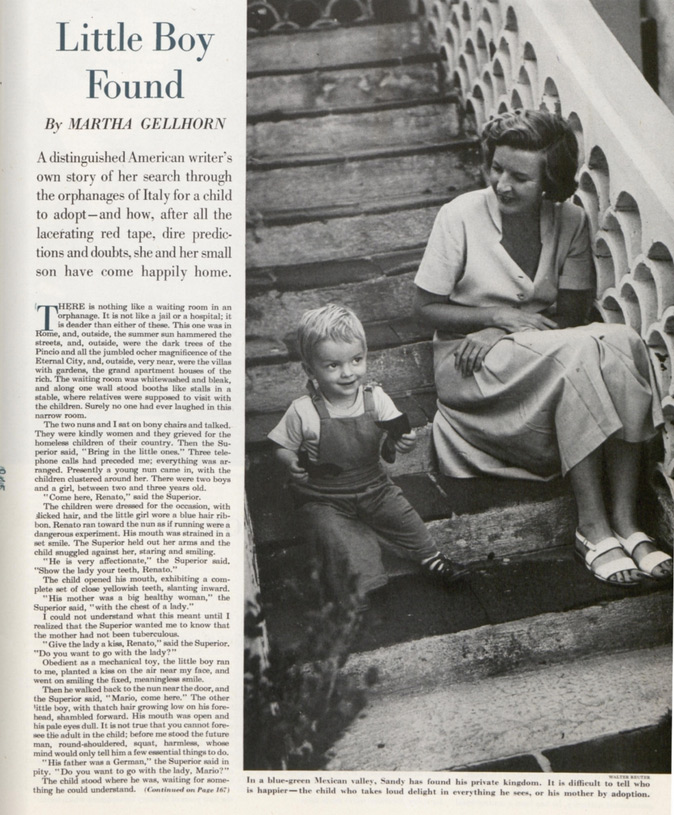

After the war, Gellhorn divorced Hemingway and lived for a time in Cuernavaca, Mexico. She continued to write for The Saturday Evening Post, first to explore the toll of the war on the street children of Rome, then to document her adoption of an Italian orphan:

I knew those children in the war. I saw them scraping an existence for themselves in the rubble of Naples; I saw them brought in, bleeding and wild, to battalion aid stations because they’d walked on mines like any soldier; I saw them dumped into trucks and moved, they didn’t know where. I thought them the bravest people possible, and beautiful and quick and cheerful in the center of hell, where they lived… They ought to declare war on grownups, I thought furiously, who killed their childhood.

Her adopted son, George “Sandy” Alexander, required letters from several ambassadors and the Roosevelts to leave with Gellhorn out of Florence.

Gellhorn’s years as a war correspondent weren’t behind her. However, she lost favor with many American publications after declaring herself firmly against the Vietnam War and Lyndon Johnson. The Guardian agreed to buy six articles from Gellhorn in 1966 when she explained her intention to carry on her style of covering everyday life during conflict: “I want to write about the Vietnamese, the civilians, whom everyone has forgotten are people. I want to try, humbly, to give them faces so we know who we are destroying.” She urged American journalists to cover Vietnam fairly instead of catering to military interests.

Gellhorn covered Nicaraguan contras, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and, in 1989, the U.S. invasion of Panama. As a lifelong pacifist, she criticized U.S. foreign policies increasingly after World War II, dubbing the U.S. a “colonial power.” Her prose aimed to expose the detriments of war, documenting intimate details of ordinary citizens. She claimed to merely write what she would see instead of attempting to offer perspectives for both sides of a conflict.

At 89 years old, blind and suffering from ovarian cancer, Gellhorn swallowed a cyanide pill in her London flat. Her New York Times obituary described her as “a cocky, raspy-voiced maverick who saw herself as a champion of ordinary people trapped in conflicts created by the rich and powerful.”

Above all, Gellhorn refused to be remembered as Hemingway’s wife. After all, it was the least interesting fact about her. “I was a writer before I met him, and I have been a writer for 45 years since,” she wrote. “Why should I be a footnote to someone else’s life?”

Correction: October 25, 2020

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Gellhorn was fired from United Press “after reporting sexual harassment by a coworker.” According to Caroline Moorehead’s biography of Gellhorn, “a visiting South American tycoon, in some way linked to the news agency, made a pass at her in a taxi.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Martha Gellhorn’s life and accomplishments are almost beyond belief for one individual. I want to read the Post features on her per the links you’ve included here.

She HAD to do what she did without permission or would have been told she couldn’t, of course. Ms. Gellhorn really cared about people, and was a fine humanitarian; always for the common good in each section of the 20th century. lf something required putting herself in harms way either physically or legally, then that’s what she did.

I was sorry to read she had ovarian cancer as an elderly woman, and lost her sight. The ending of her life, I feel, was a permanent euthanizing of herself, by her own choice, when all hope was gone. No one has the right to criticize or judge her negatively for it.

This article has commonality with Ben Railton’s feature on Fanny Fern from earlier this year, despite the vast differences in times and circumstances. Cancer took her life as well unfortunately, at a much younger age. Please continue to find features like this in the Post’s unique archives.