Vintage Ads: Travel in the 1950s

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

March 3, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

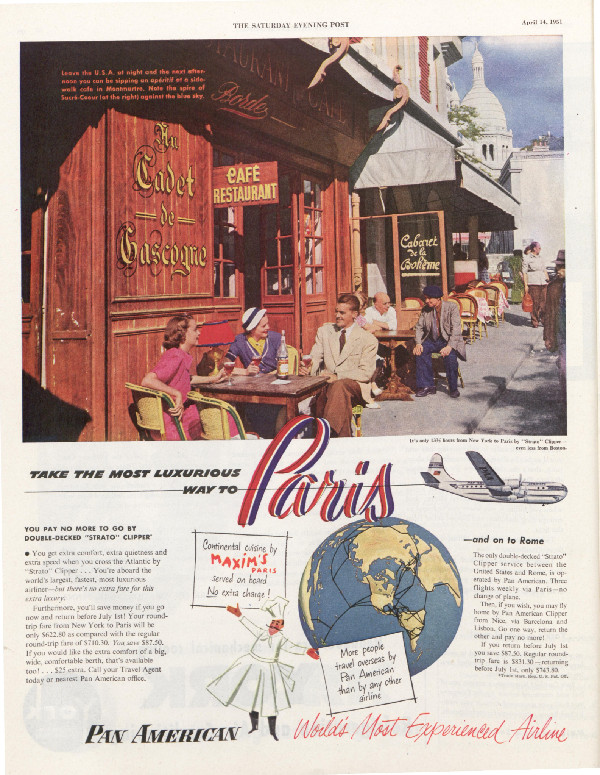

April 14, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

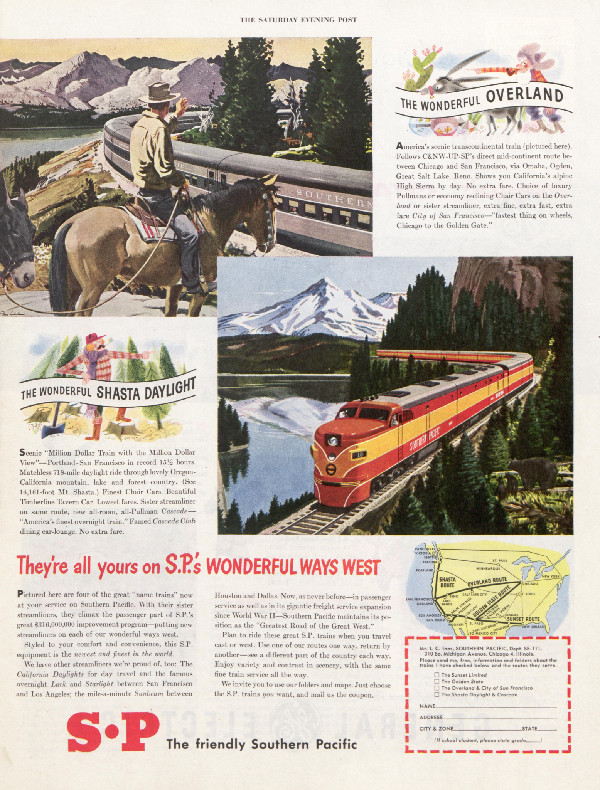

November 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

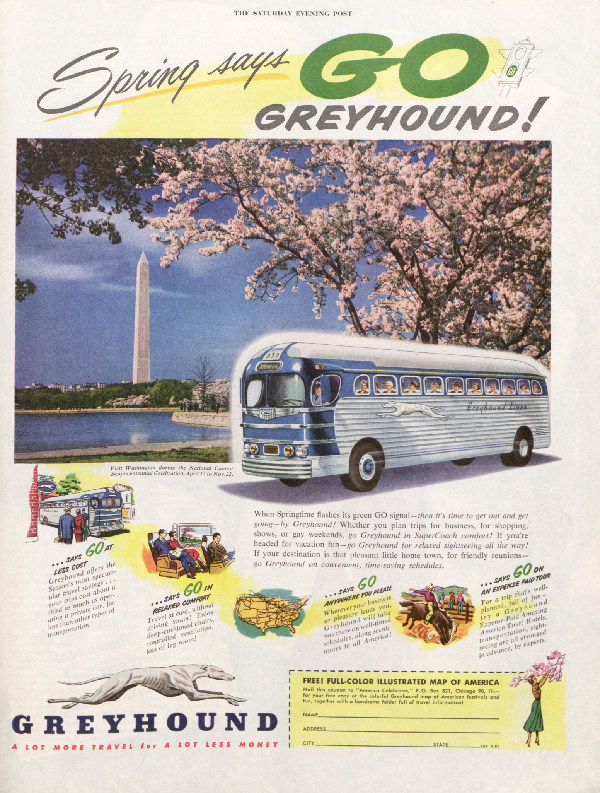

November 18, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

December 1, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

July 1, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

June 24, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 1, 1952

(Click to Enlarge)

October 6, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

The Art of the Post: The Art of…the Refrigerator?

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

The first practical refrigerators were invented a century ago and instantly transformed American domestic life. The Saturday Evening Post was flooded with advertisements for the strange new devices. Illustrators were hired to help the public imagine how refrigerators would fit into a home and envision the role they could play. Some were more successful than others.

Inventor Fred Wolf of Ft. Wayne, Indiana started the rush in 1913, with the announcement of the first refrigerator for home and domestic use. A year later, an engineer in Detroit jumped in with his suggestion for an electric refrigerator, the predecessor of the famous Kelvinator. By 1918, the demand for the new invention had become clear, and the Frigidaire company was founded to mass produce refrigerators.

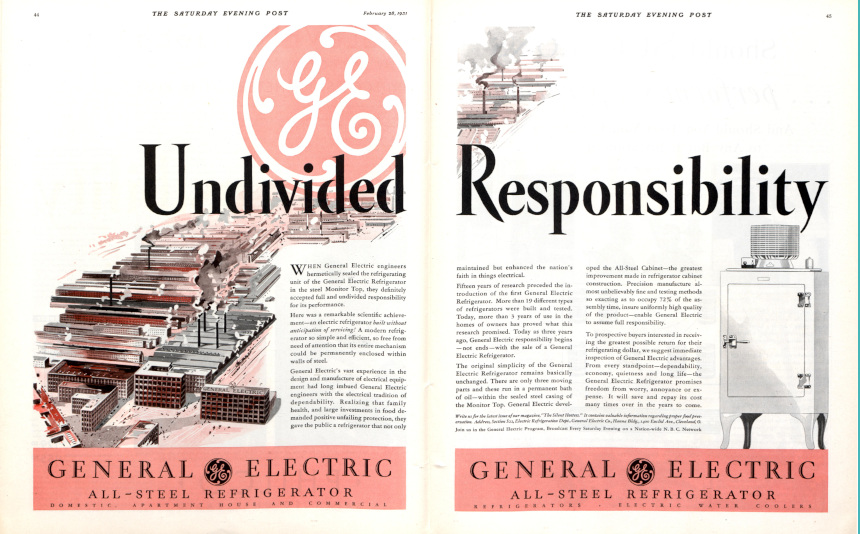

Rival companies popped up, each trying to outdo the others with features they thought the public might like. For example, Kelvinator touted the first refrigerator with an automatic control. Electrolux offered what it called the first “absorption refrigerator.” Inventors and engineers battled over the science. Here is a two-page ad from the Post bragging about the factory where the “hermetically sealed refrigerating unit” is contained within the “steel monitor top.”

But it took art, not science, to humanize the strange new invention. Refrigerator companies faced a big challenge selling the new invention to everyday Americans; in 1922 a refrigerator could cost over $700 while a new car (the Model T Ford) cost only $450. The public wouldn’t buy refrigerators without a vision for how they would fit into the American lifestyle.

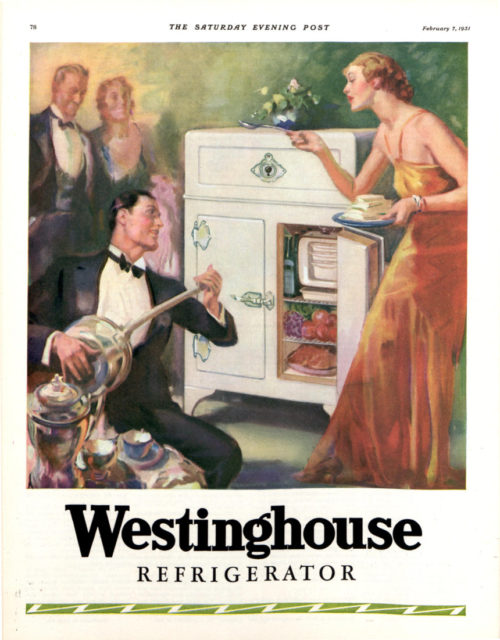

Here we see a 1929 painting by Walter Biggs of a high-class social event:

The men are wearing tuxedos and the women dressed in fashionable gowns. They smile as they exchange witty banter about cultural events. But the real star of the party—and the whole reason for the painting—is that brand new refrigerator in the far right hand corner.

Right smack dab in the center of the painting is the modern miracle… glasses filled with ice! Ice was readily available for guests for the first time with the invention of the refrigerator. Today we wouldn’t think of keeping our refrigerator in the middle of our dining room with the guests, but this picture tells us that it was a mark of prestige.

Next, this enterprising artist tries to portray the refrigerator as a springboard to romance. (Hah! Good luck with that!)

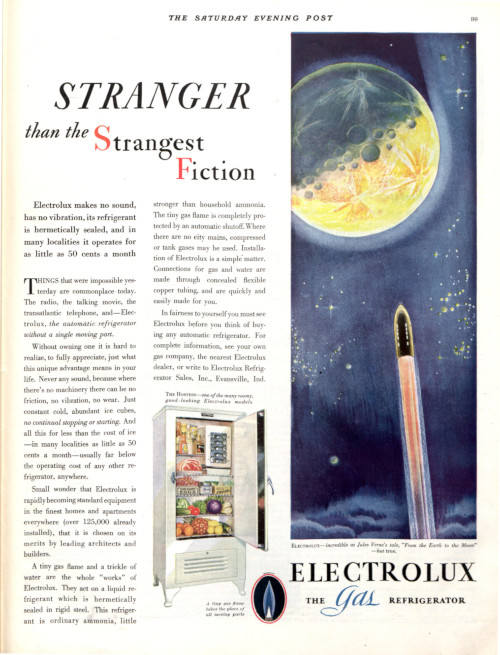

Another artist felt he could make the new invention popular with a “science fiction” approach:

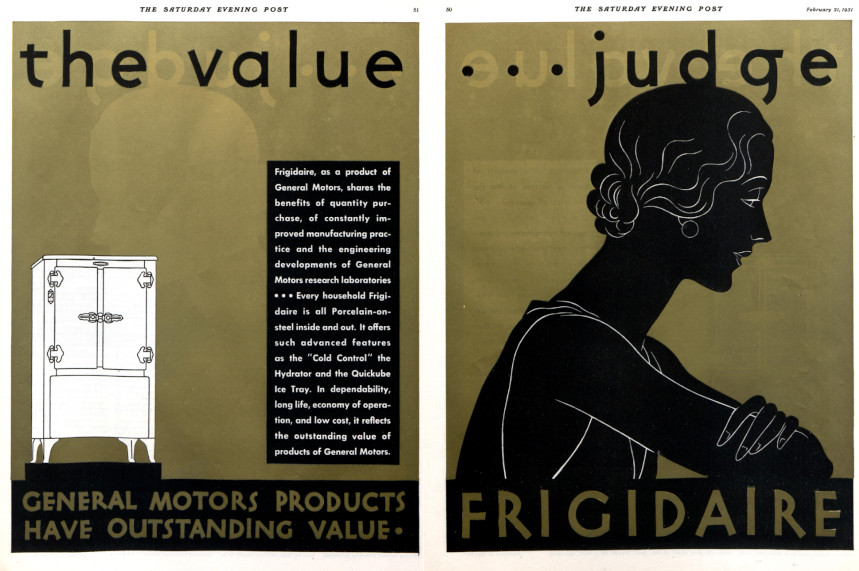

This artist does his best to make a white metal cube look stylish by making it a tiny element in a large, black and gold art deco picture. Note that Al Dorne’s harried, overworked housewife has become an elegant young woman of leisure in an evening gown.

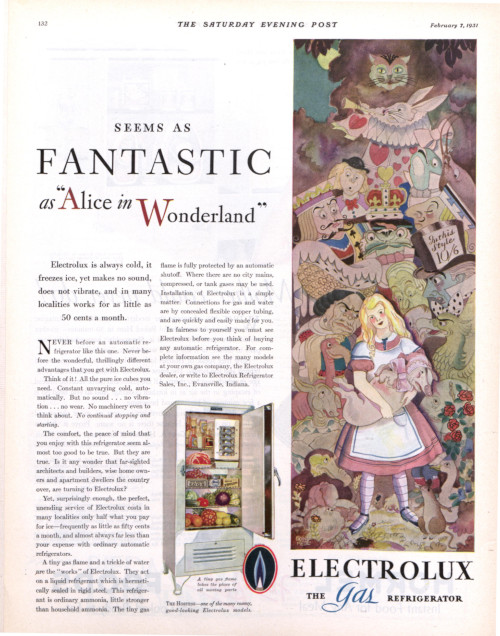

There were even illustrations for consumers who felt that a refrigerator was “like magic.”

Today many of these approaches seem silly to us, but in the beginning before the identity of the refrigerator had been firmly established, artists could let their imaginations run wild.

It always takes a while for people to figure out the proper role for the new invention; when trains first arrived on the scene, they were noisy and frightening. They spooked horses and polluted the environment with smoke and cinders. But artists and musicians and storytellers began to humanize the new machine, singing folk songs and telling tales, and pretty soon we welcomed trains into our cultural heritage.

We rely upon the artistic imagination to help us view our strange new inventions and assimilate them into our natural world. Nothing like the refrigerator had ever existed before, so there were no precedents for artists to rely on. Some of the earlier efforts make us laugh today, but eventually illustrators found their footing.

Featured image: Courtesy of the Kelly Collection of American Illustration

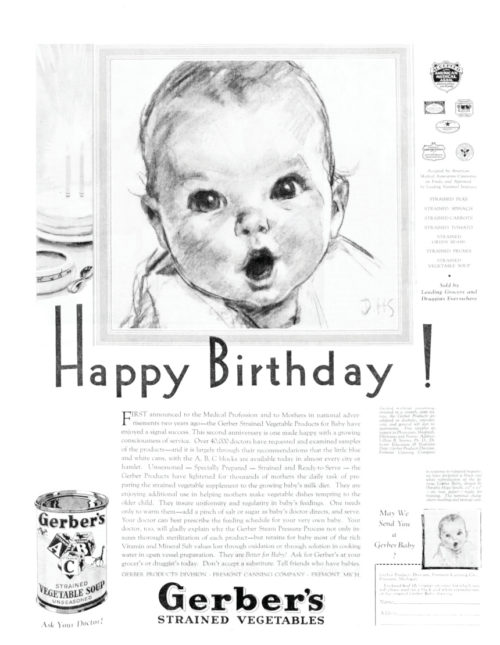

Vintage Ad: Who Was That Gerber Baby?

In 1927, when Dan Gerber saw his wife struggling to strain food for their baby, he was inspired to start making baby food at his canning factory in Fremont, Michigan. The next year, as part of its national roll-out campaign, Gerber Baby Foods ran the ad below in the Post.

Wanting an infant’s picture for their label, the company asked artists to submit possible portraits. Dorothy Hope Smith, a child portrait painter, sent in a charcoal sketch of a neighbor’s infant daughter. She told the judges she’d finish it in color if they selected her picture, but the judges liked the image just as it was: they refused to let Dorothy complete it. Her preliminary sketch has been used, unchanged, ever since.

For years, the identity of the baby was a matter for speculation. There were rumors that the child grew up to be someone famous. One candidate was Humphrey Bogart (who was 29 years old the year the sketch was made). Other guesses were Elizabeth Taylor, Bob Dole, and Jane Seymour. All wrong. The baby was Ann Turner Cook, now a retired school teacher in Florida, who has been seeing her baby face in grocery stores for more than 90 years.

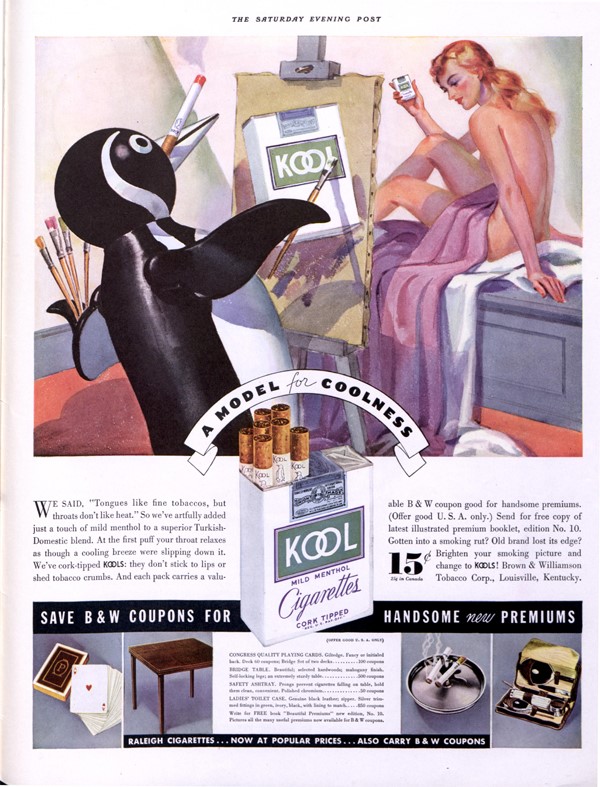

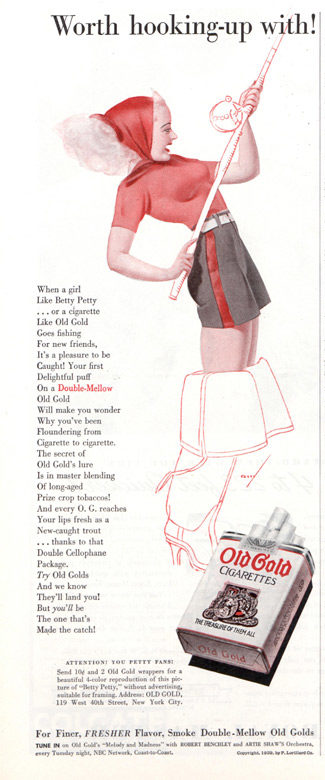

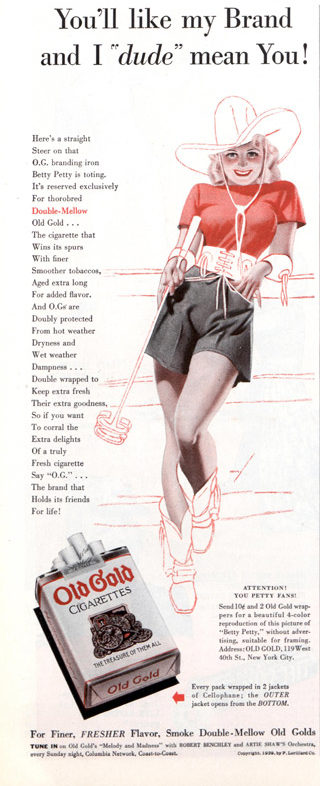

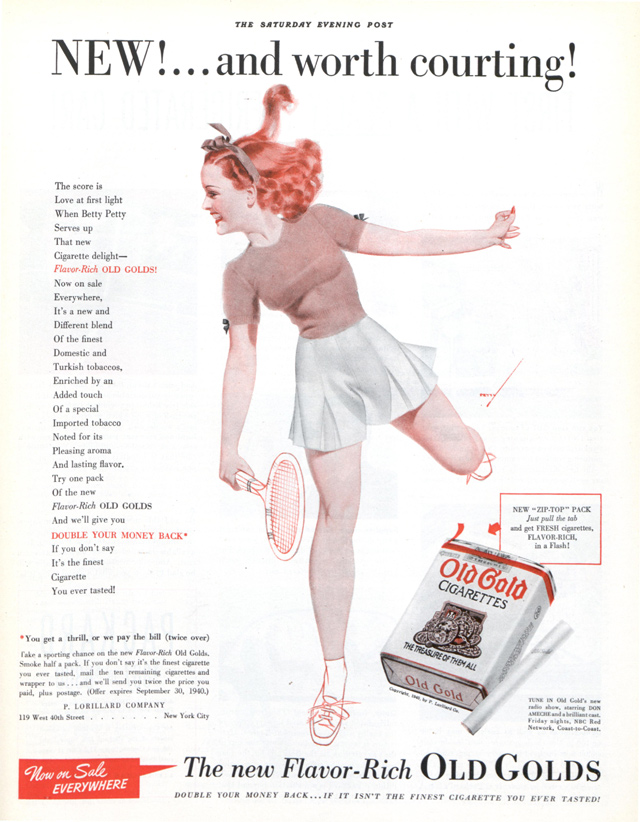

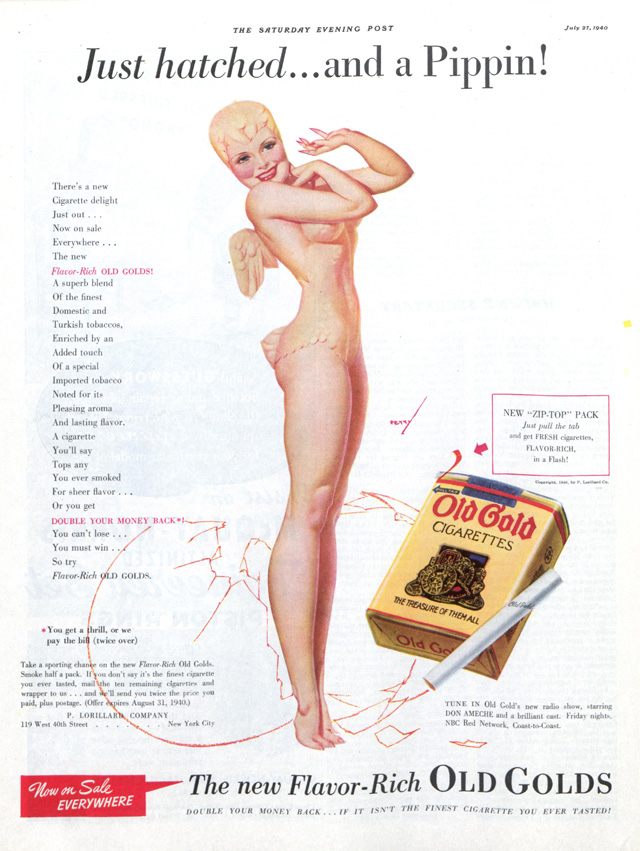

Vintage Ads: Selling Cigarettes with Sex

Sex sells. Desirable women, rugged men, and suggestive slogans have all been a part of advertising for more than a century. This collection of vintage cigarette ads reveals some of the ways tobacco companies used sexual themes and risqué imagery to sell cigarettes.

The tobacco industry began using such tactics in the 1880s when they began printing pictures of women in costumes on the piece of cardstock used to hold the shape of the cigarette pack — a precursor to baseball cards.

Duke, Sons & Co. was the leading cigarette brand in the 1880s and early 1900s. The cardstock images they included in their packages became collectors’ items.

Headlines in tobacco ads were often double entendres, inviting readers to decide whether they were talking about their product or the person pictured in the ad.

Tobacco companies often chose attractive women to star in their ads to attract the male audience. Although sexual references primarily targeted men, they also lured women.

According to studies done in 2007 by Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising (SRITA), women were manipulated to believe that if they smoked cigarettes, they would be sexier and more attractive to men.

SRITA also found that if tobacco companies used slim women with fashionable clothes, women would be enticed to smoke.

Research shows that sexual imagery tends to grab consumers’ attention more quickly than a non-sexual ad and holds their attention longer. A study done by the University of Georgia (UGA) concluded that sex really does sell.

A UGA researcher explains that “people succumb to the ‘buy this, get this’ imagery used in ads.” They subconsciously believe that buying the product will make them as attractive as the people portrayed in the ads.

So what exactly were tobacco companies selling? An image, a fantasy, sex. And maybe a cigarette or two.

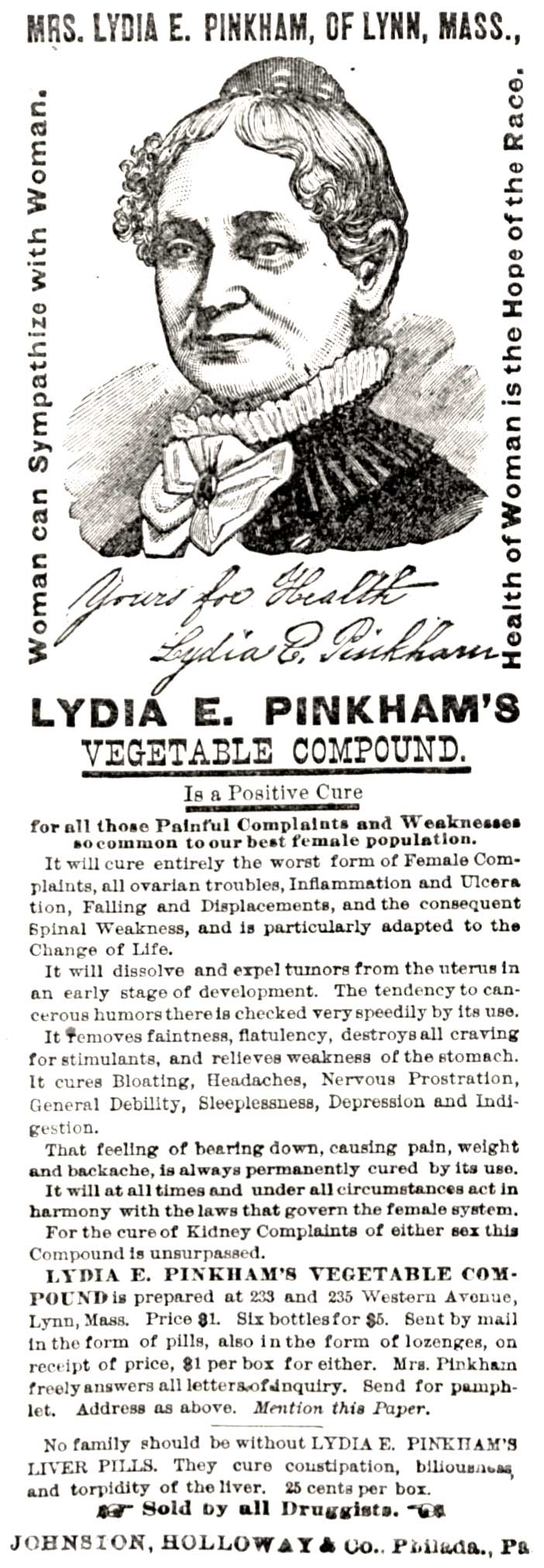

Pinkham’s Cure for ‘Women’s Complaints’

Post readers of the 1880s would have been familiar with this woman’s face. Lydia Pinkham was nationally renowned as the creator of one of the most trusted of all patent medicines. Born in 1819, Pinkham was a Massachusetts homemaker who treated her family’s ills with homemade herbal medicines. She concocted her Vegetable Compound for women to help them ease menstrual and menopausal discomforts. For years, she shared this brew with grateful neighbors. Then, in 1875, with her family in a financial crisis, she began selling her medicine.

The formula included orange milkweed, black snakeroot, unicorn root, and fenugreek. But perhaps the most effective ingredient was a generous dose of alcohol. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound was a 36-proof brew. Pinkham, who strongly supported the temperance movement, didn’t list the alcohol content on the package.

Patent medicines became so extravagant in what they claimed they could do that the government took action in 1906 with the Pure Food and Drug Act. It required medical manufacturers to list their contents and stop making unsubstantiated claims for their remedies. (Years earlier, when Cyrus Curtis purchased the Post, one of his first actions was to prohibit all patent medicine ads.) When consumers learned about Pinkham’s actual ingredients and its limited claims for cures, sales dropped off. Yet many women stayed loyal to Lydia and continued to use the product. In fact, it is still being made today, though by a different company and with less alcohol and more modest claims of its powers.

This vintage ad is featured in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

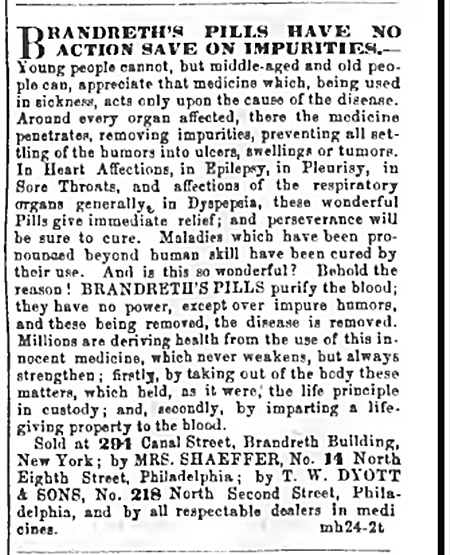

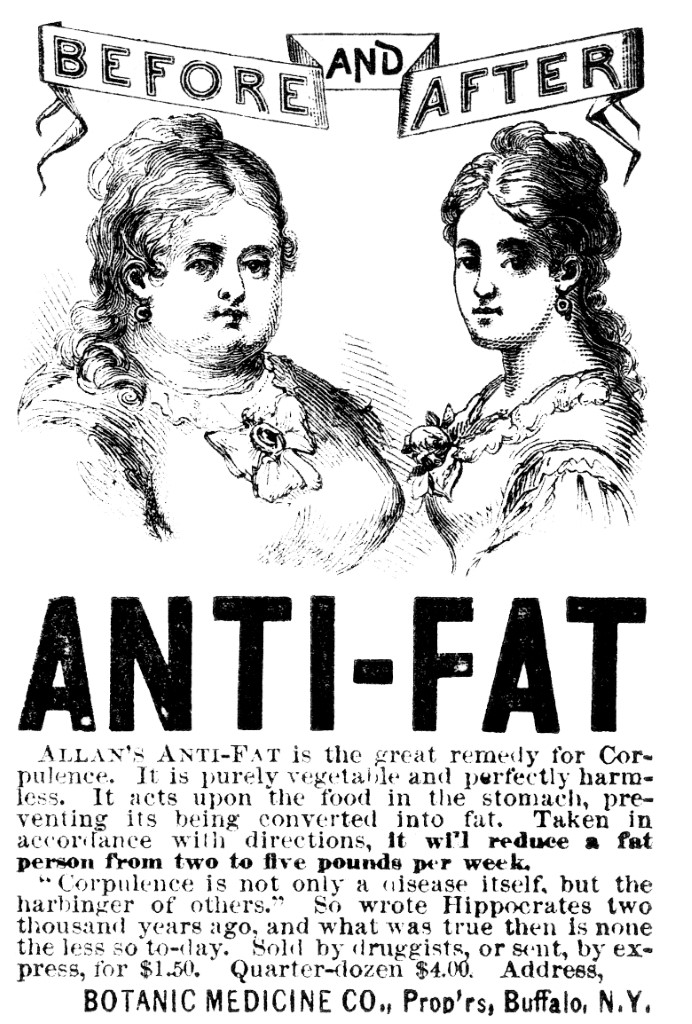

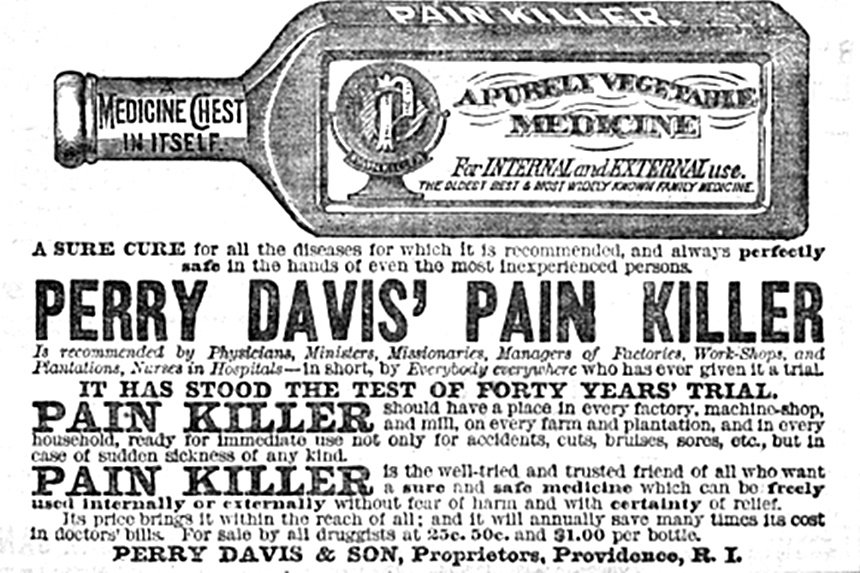

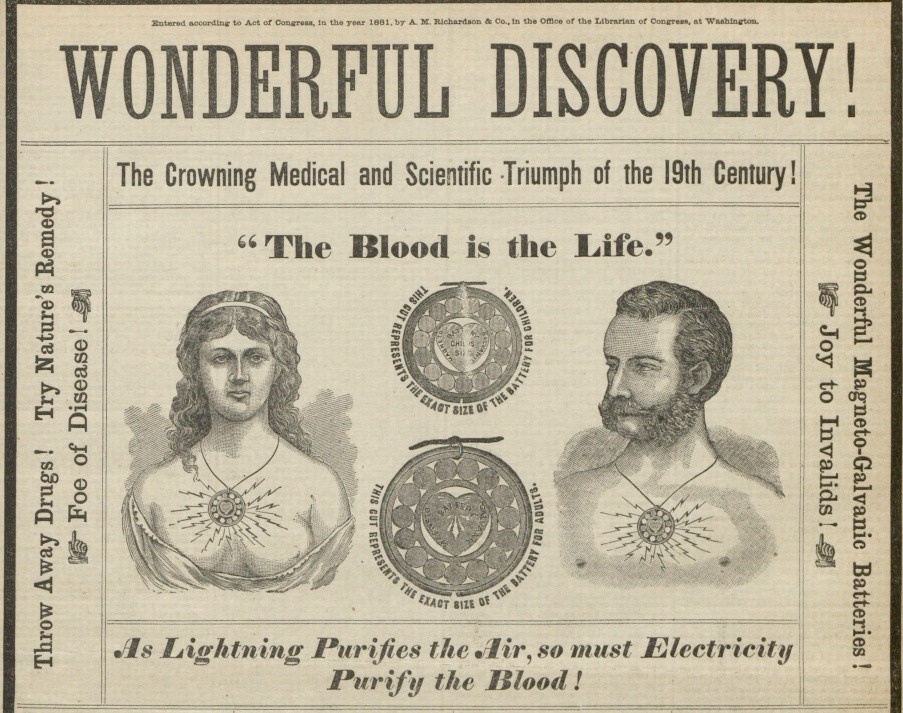

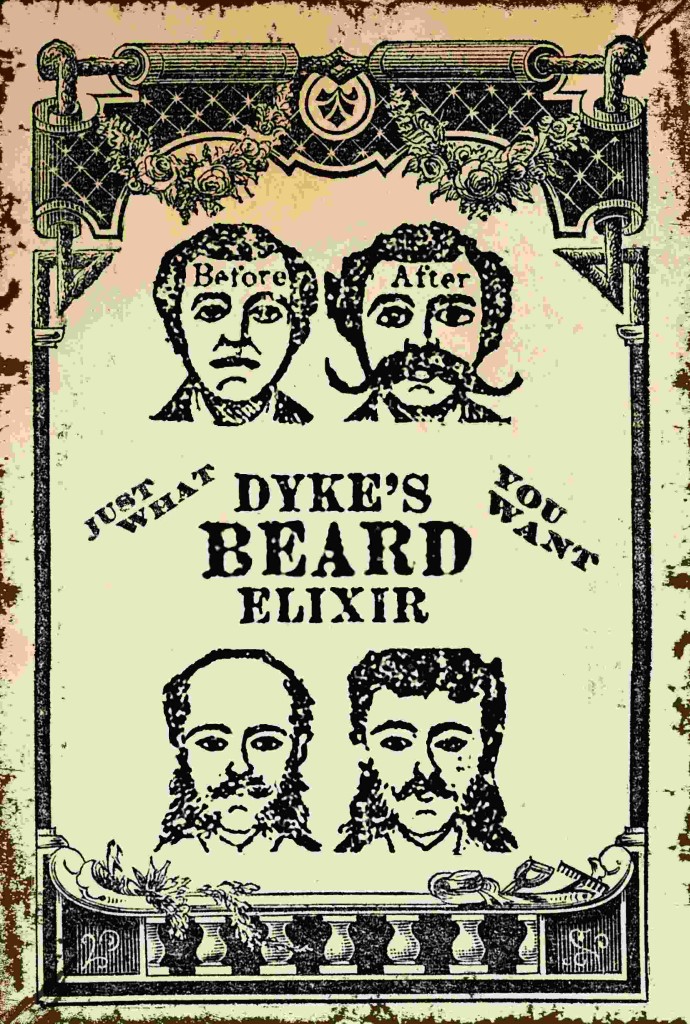

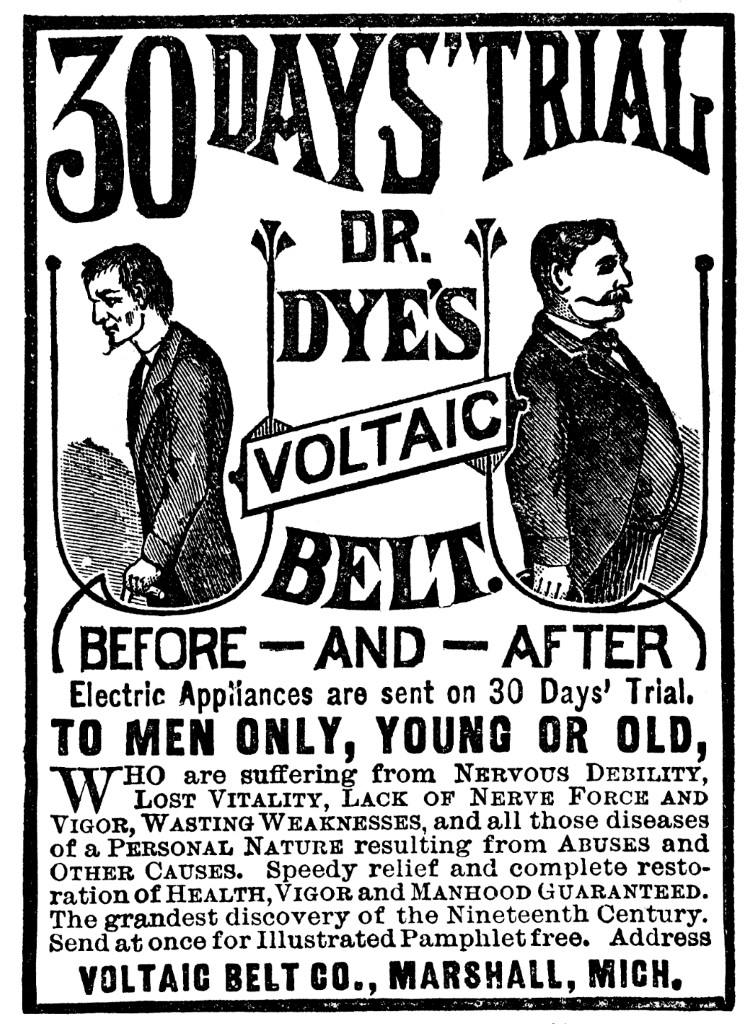

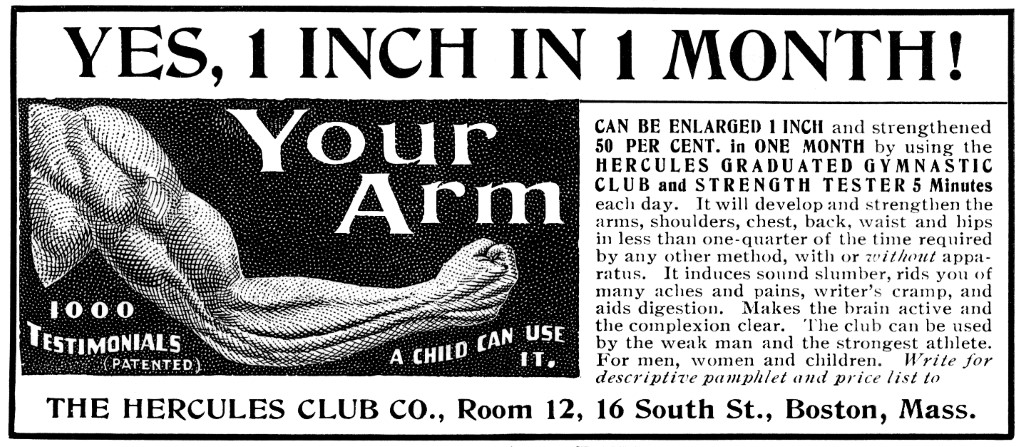

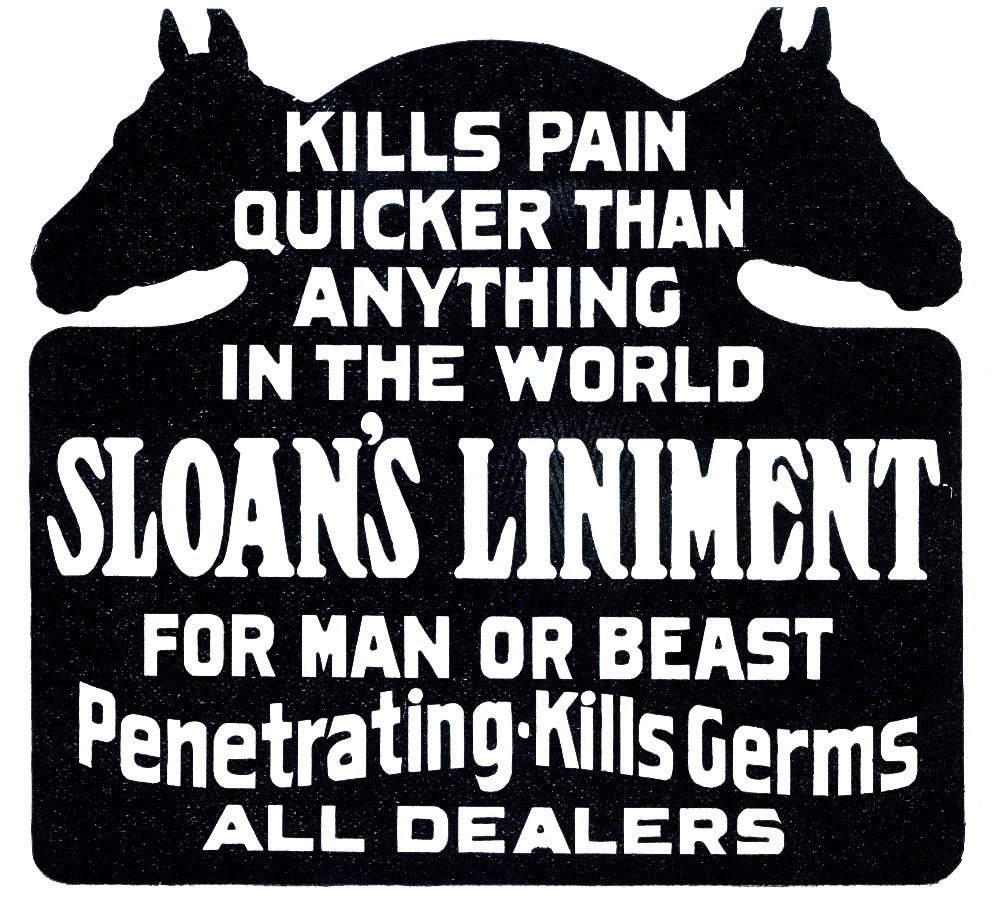

Vintage Ads: Tonics, Elixirs, and Gadgets for Health

Looking for a salve to soothe your soul or a tonic to tweak your physique? These advertisements that appeared in the late 1800s and early 1900s in the Post promised to fix everything from extra girth to self-worth.

March 31, 1860

July 6, 1878

March 25, 1880

January 29, 1881

June 17, 1882

June 30, 1883

April 27, 1901

September 29, 1904

Become a subscriber to gain access to all of the articles, covers, and advertisements of The Saturday Evening Post dating back to 1821.