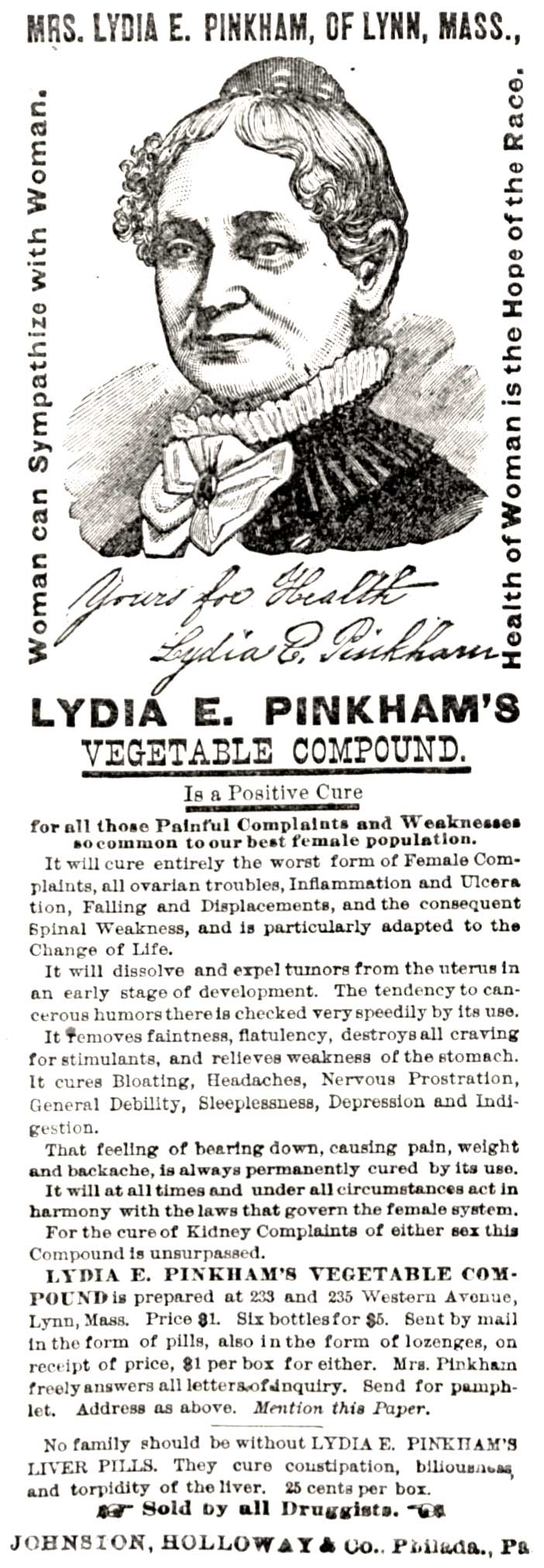

Post readers of the 1880s would have been familiar with this woman’s face. Lydia Pinkham was nationally renowned as the creator of one of the most trusted of all patent medicines. Born in 1819, Pinkham was a Massachusetts homemaker who treated her family’s ills with homemade herbal medicines. She concocted her Vegetable Compound for women to help them ease menstrual and menopausal discomforts. For years, she shared this brew with grateful neighbors. Then, in 1875, with her family in a financial crisis, she began selling her medicine.

The formula included orange milkweed, black snakeroot, unicorn root, and fenugreek. But perhaps the most effective ingredient was a generous dose of alcohol. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound was a 36-proof brew. Pinkham, who strongly supported the temperance movement, didn’t list the alcohol content on the package.

Patent medicines became so extravagant in what they claimed they could do that the government took action in 1906 with the Pure Food and Drug Act. It required medical manufacturers to list their contents and stop making unsubstantiated claims for their remedies. (Years earlier, when Cyrus Curtis purchased the Post, one of his first actions was to prohibit all patent medicine ads.) When consumers learned about Pinkham’s actual ingredients and its limited claims for cures, sales dropped off. Yet many women stayed loyal to Lydia and continued to use the product. In fact, it is still being made today, though by a different company and with less alcohol and more modest claims of its powers.

This vintage ad is featured in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Mrs. Pinkham had to have been on the right track or she never would have been so successful in the late 1800’s to the present day, despite formulation changes. Though not a doctor nor scientist, she knew what she was doing in developing an aid that indeed helped a lot of women.

She may have gone a touch too far with some of the ad claims and the alcohol strength, but meant well. I didn’t see ‘hot flash elimination’ as one of the claims. My Mom (and her friends) complained about THAT one after ‘the change’ in the late 1980’s and 90’s. Their doctors put them on Premarin (hormone replacement) which was a God send in getting rid of that problem.

A few years into it, her friend Cassie found out what it was made from, and Mom WAS a little stunned. She basically told her though, “frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn!” They were capsules after all, so don’t say ‘neigh’ too quickly. It’s still on the market, along with newer products. Whatever works: because life is tough enough.