Considering History: Voter Suppression and Racial Terrorism, the Twin Pillars of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

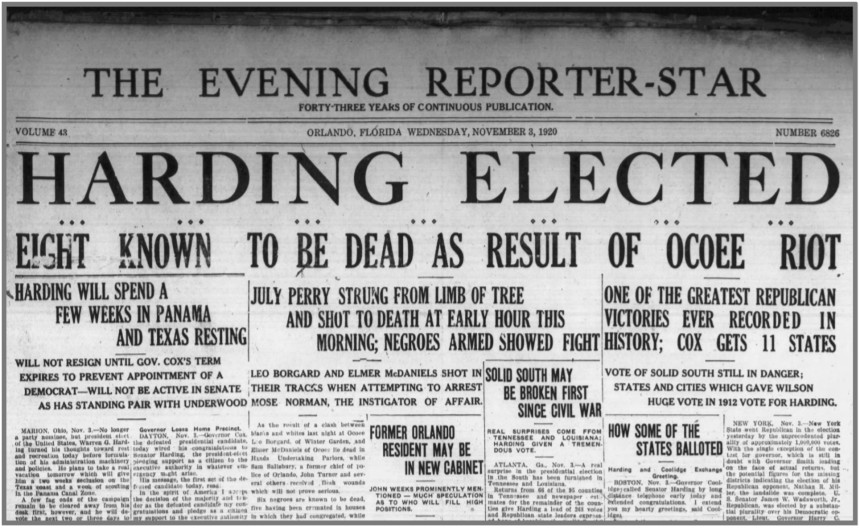

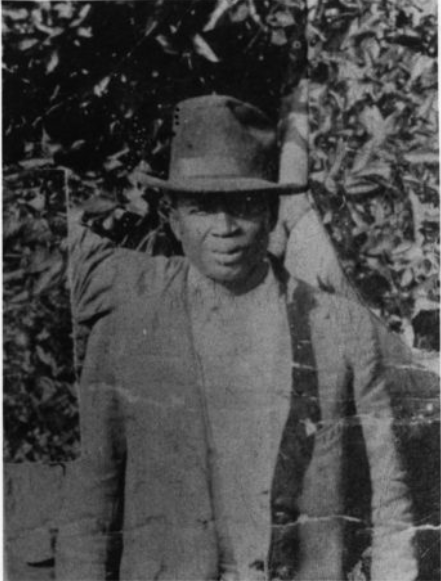

On November 2, 1920, as voters across the country went to the polls to decide a presidential election between two Ohio politicians, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding and Democratic Governor James M. Cox, violence erupted in the Florida town of Ocoee. Local African-American farmer Mose Norman tried to exercise his Constitutional right to vote, and was turned away twice under the pretense of the state’s Jim Crow efforts to disenfranchise black voters. An angry white mob then pursued Norman, laying siege to the home of another man, Julius “July” Perry. Perry fired on the attackers in self-defense, and the mob seized upon that action to terrorize the town’s Black community, eventually killing Perry and more than fifty other African-American residents, burning down homes and businesses, and forcing much of the rest of the community to flee the town.

The Ocoee massacre, known as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history,” had its roots in multiple historical trends. Like states throughout the Jim Crow South, Florida had developed in the 50 years since the 15th Amendment’s ratification numerous legal measures and social practices intended to make it impossible for African Americans to vote. But those longstanding voter suppression measures were complemented by a much more immediate, violent threat of force: the day before the election, members of the newly resurgent, 2nd Ku Klux Klan had marched through Ocoee, proclaiming through megaphones that “not a single Negro will be permitted to vote.” And no 1920 act of racial terrorism can be separated from the prior year’s epidemic of such violence, the year-long series of lynchings and massacres that came to be called the “Red Summer of 1919.”

Those factors help us understand the divisions and discriminations at the heart of American culture in 1920. But on the 100th anniversary of the Ocoee massacre, and as we approach another election day, that specific historical event can also help us to better recognize an overarching, profoundly relevant American trend: the way in which voter suppression has consistently gone hand in hand with racial terrorism to prop up white supremacy.

In recent years, we’ve started to do a better job of remembering the history of white supremacist racial terrorism in America through such vehicles as public memorials and pop culture texts, including horrific individual events such as the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the century-long lynching epidemic. But too often the stunning brutality and destruction of those acts of violence can make them seem like impromptu explosions, perhaps reflecting consistent undercurrents of racism but not the result of purposeful, extensive, organized political planning.

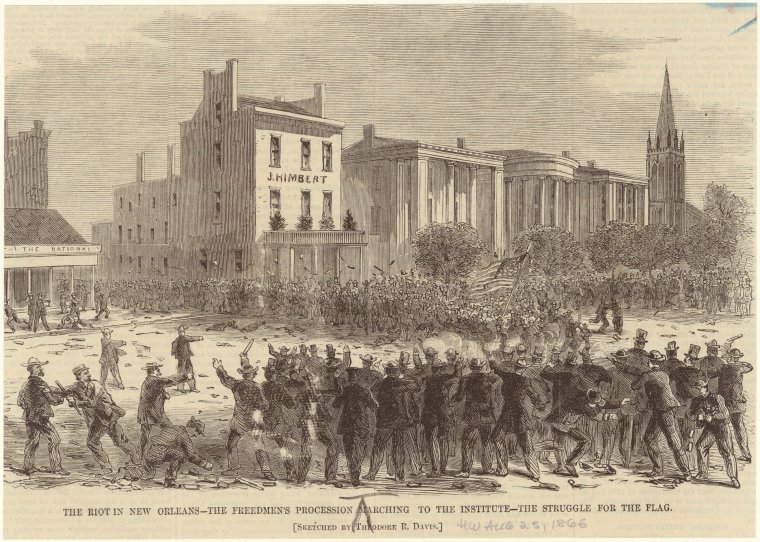

Yet the truth is that these acts of racial terrorism have consistently been tied to planned, organized, systematic plans for voter suppression and related political agendas, as illustrated by not just Ocoee in 1920, but also three prominent 19th century massacres and one from the Civil Rights era. The July 30, 1866 New Orleans massacre began when white supremacists attacked 130 African-American residents marching toward the Louisiana Constitutional Convention at Mechanics’ Institute; the state legislature had passed a series of Black Codes barring Black men from voting (among many other discriminatory effects), and the marchers were hoping to join the Convention to advocate for their rights. New Orleans’ newly re-elected Confederate mayor, John T. Monroe, led a group of ex-Confederates, police officers, and other white supremacists to attack the marchers, starting a massacre that would end with more than 200 African-American Union Army veterans and another 200+ Black civilians killed.

Despite such racial terrorism, African Americans continued to exercise their Constitutional right and active patriotic goal of voting, and were consistently met with extensive suppression and violence. On November 3, 1874, African-American voters at the polls in Eufaula and Spring Hill, towns in Alabama’s Barbour County, were attacked by members of the widespread white supremacist organization The White League; seven African Americans were killed and another 70 wounded. The Barbour County massacre was one of many such events throughout the South on that 1874 election day, a planned campaign of voter suppression and violence after which League-affiliated officials also threw out legitimate votes for Republican candidates and helped install sympathetic Democratic officials in their place (a shift often defined as the beginning of the end of Federal Reconstruction).

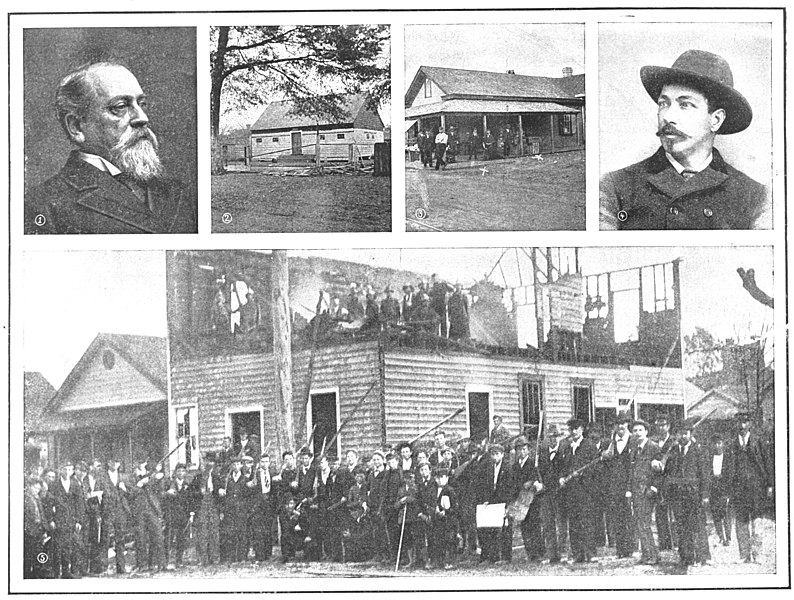

The November 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) coup and massacre originated from even more overtly organized voter suppression goals. By late 1898 Wilmington was one of the last communities in North Carolina (and the entire Jim Crow South) not governed by white supremacists — the so-called “Fusion” Party, featuring African-American political figures and their Republican and Populist white allies, had in the 1896 election held on to many of the city’s positions. White supremacists targeted the next election day, November 8, 1898, as an occasion to reverse that trend by force and violence: planning for months an extensive program of both voter suppression and systemic violence, alongside an accompanying propaganda campaign in the media, that resulted in both a coup d’etat and a massacre that devastated the city’s African-American community.

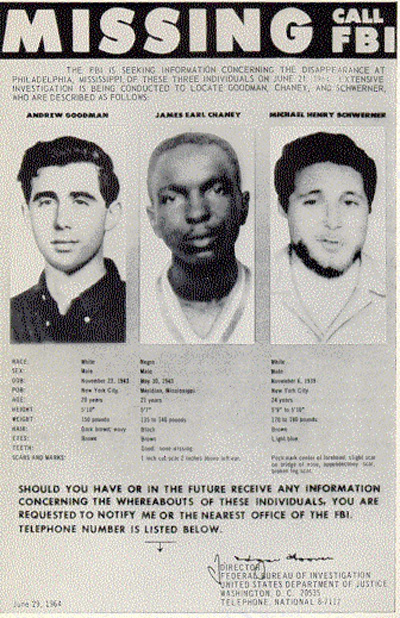

One of the latest documented lynchings, the infamous June 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi, was similarly interconnected with voter suppression. The three men were working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as part of its Freedom Summer campaign to register African-American voters in Mississippi and throughout the South, and were on their way to a registration event at a local church when they were pulled over by local law enforcement. An extensive FBI investigation determined that members of the Philadelphia Police Department, the Neshoba county sheriff’s office, and the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan subsequently abducted and killed the men. The collaboration between those official and domestic terrorist organizations doesn’t simply reflect their overlapping membership; it also illustrates that the murder of these voting rights activists was part of a political campaign to suppress African-American votes and keep these white supremacist forces in power.

Throughout American history, those who have fought for the right to vote have had to do so in direct opposition to some of the nation’s most powerful forces, including white supremacist suppression and violence. Those battles continue into the 21st century, and as we continue to fight for and to exercise the right to vote, it’s vital that we remember the foundational and consistent ties between voter suppression and white supremacist racial terrorism.

Featured image: The New Orleans Massacre (Artwork by Theodore R. Davis for Harpers Weekly / Wikimedia Commons)

5 Ways Your Vote Might Not Count

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was meant to break down obstacles to voter registration that had kept minority groups out of the polls for most of American history. Besides outlawing literacy tests, the act allowed the U.S. attorney general to investigate poll taxes, which had been banned for federal elections in 1964, and state elections in 1966. Section 5 of the act required federal oversight of 11 states where at least 50 percent of the non-white population was not registered to vote.

The Voting Rights Act was seen as a major victory of the civil rights movement and was considered a breakthrough in making sure every citizen had access to one of their most basic rights.

Half a century later, having a voice in American government is not as simple as showing up to the polls on election day. Here are five reasons your political voice may go unheard.

1. Use-it-or-lose-it Registration Laws

It’s impossible for your vote to count if you never get to cast it. Some states have instituted strict registration laws that make it harder for potential voters to stay registered. One example is Ohio’s “use-it-or-lose-it” law that allows the state to unregister voters who have not cast a ballot in a set amount of time. If you go two years without voting the state sends you a warning in the form of a post card. If you go a further four years (missing one presidential election) without responding or voting, the state removes you from voter rolls.

This law was upheld by the Supreme Court case Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute in 2017. It has contributed to the removal of two million voters between 2011 and 2016. And, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissenting opinion, “has disproportionately affected minority, low-income, disabled, and veteran voters.”

2. Exact Match System

The exact match system also presents an obstacle in voter registration. This Georgia law requires the name on your ID to exactly match the name on your registration form. Using “Jim” on the form and having “James” on your ID, for example, would result in disqualification. Even one hyphen or letter out of place will prevent you from voting.

Critics of this system also argue that the exact match system unfairly affects communities of color, as their names would be less familiar to workers entering names into voter registration systems. As such the exact match system has come to be known as “disenfranchisement by typo.”

3. Mailing Address Required

North Dakota requires a current street address as voter identification. This policy prevents voters without a residential street address from registering to vote.

More specifically, most Native Americans living on reservations, (more than 18,000 in North Dakota), use P.O. boxes instead of residential addresses. The policy dictates that the address must be a street address and does not accept P.O. boxes, keeping those living on reservations from the polls. The Supreme Court upheld this law in 2018.

4. Felons Can’t Vote

All but two states (Maine and Vermont) revoke your right to vote upon conviction of a felony. In 14 states and Washington, D.C., this right is automatically restored upon release. In 22 states the right to vote is restored after a waiting period, completion of parole, or independent action of voters. The remaining 12 states require further action to restore the right (such as longer waiting periods or a governor’s pardon) and for some crimes the right to vote is never restored.

In 2018 Florida passed a law that would restore the right to vote to former felons who have already paid their debt the society. This law gave voting rights to 1.4 million people, the largest mass enfranchisement since the Voting Rights Act. This brief moment of victory was quickly followed with a law passed in May of 2019 that required all former felons to pay off back fines and fees to the court before they can vote again. Similar laws exist in four other states, and three states require former felons to personally apply to state legislatures for their voting right to be restored (Arizona requires this only for second-time offenders).

5. Finding a Polling Place

The Voting Right Act’s Section 4 was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2013. The Shelby County v. Holder decision stated that times have changed and states with a long history of voter suppression no longer needed voting policies monitored by the Attorney General or a Washington, D.C. district court. A 2016 study by the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that “Out of the 381 counties [formerly under federal supervision], 165 of them — 43 percent — have reduced voting locations.” At the time of the study, 868 polling locations had closed across the previously monitored states. The closures have continued since 2016.

In Georgia, specifically, over 200 polling places have closed in recent years. The Leadership Conference study claims that the lack of polling places and early voting locations “place[s] an undue burden on minority voters, who may be less likely to have access to public transportation or vehicles, given continuing disparities in socioeconomic resources.”

Voting is much more complicated than simply showing up. The Voting Rights Act aimed to include more Americans in the political discussion. but there is still more that needs to be done. As Lyndon B. Johnson said when introducing the Voting Rights Act “There is no moral issue. It is wrong–deadly wrong–to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country.”

Featured image: Shutterstock