This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

If you’re like me, much of the news has felt pretty close to apocalyptic for some time now, but the first month of 2020 has taken things to another level. The assassination and reprisal that pushed the U.S., Iran, and perhaps the world to the brink of war. The raging Australian wildfires that killed billions of animals, sent smoke as far away as New Zealand, and (along with the seemingly constant Puerto Rican earthquakes) foreshadowed a year of accelerating climate catastrophes. The deadly mega-virus that is sweeping China and Southeast Asia and has led the World Health Organization to declare a global emergency for only the sixth time in its history. The impeachment debates in which a prominent Republican Senator admitted in an extended Twitter thread that the president illicitly sought foreign interference in the 2020 election and illegally covered it up — and then that Senator voted not to have witnesses at the trial.

In light of all these and so many other stories, it can feel difficult, if not downright impossible, to maintain hope for the future. But there’s a corollary concept to the critical patriotism I discussed in my Martin Luther King Day column: critical optimism. This form of optimism, which I defined and advocated as part of my book History and Hope in American Literature: Models of Critical Patriotism (2016), recognizes and engages with the hardest and worst of our world, yet seeks to find reasons for hope nevertheless, not despite those realities but through and beyond them. And as we begin Black History Month, it happens that one of the most critically optimistic texts I know was authored by an African-American author and focuses on an act of racial terrorism: Charles W. Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition (1901), a historical novel inspired by the horrific 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) white supremacist coup and massacre.

Chesnutt’s life and career themselves modeled critical optimism in response to some of America’s bleakest realities. The grandson of enslaved people and son of two free African Americans who moved their family from North Carolina to Ohio just before the Civil War, Chesnutt chose to return to North Carolina after the war and work as an educator and principal during Reconstruction. Both of his grandfathers were likely white slave owners and he was light-skinned enough to be mistaken for white many times in the course of his life, but Chesnutt consistently and publicly defined himself as African American and dedicated his writing career to (as he wrote in his journals) “exalt my race.” And when editors and publishers sought to pigeon-hole his writing into the late 19th century’s “plantation tradition” genre, he both exploded that genre’s conventions (in his book of “conjure tales”) and wrote socially realistic and politically activist novels that defied such categorizations altogether.

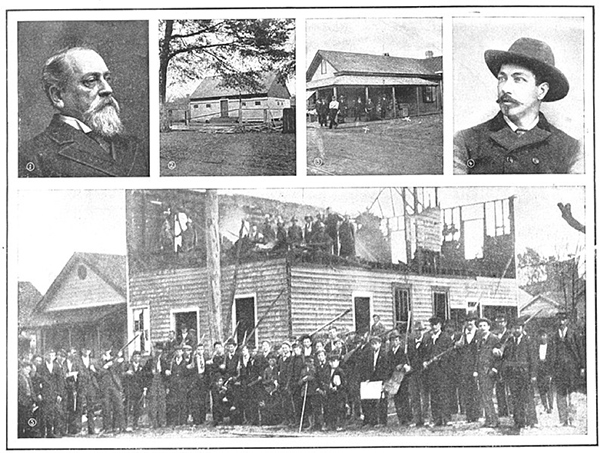

The best of those novels, and one of American culture’s most vital representations of both horrific histories and critical optimism, is The Marrow of Tradition. Chesnutt’s North Carolina roots and life were in Fayetteville, about 90 miles northwest of Wilmington, but he had many relatives and friends in the Wilmington area and knew the city well. As of 1898, Wilmington was one of the few cities in the state (and indeed throughout the South) in which the region’s resurgent white supremacists had not taken power; the city’s mayor and most other elected officials were at the time part of the Fusion Party, a progressive North Carolina political movement that brought together African Americans and radical white allies. White supremacists were frustrated by that state of affairs and angered by a newspaper editorial in which Alexander Manly, the African-American owner and editor of the Wilmington Daily Record (perhaps the only black-owned daily paper in the nation), highlighted the horrific truths of the lynching epidemic. As a result, the white supremecists spent months planning a domestic terrorist attack on the city.

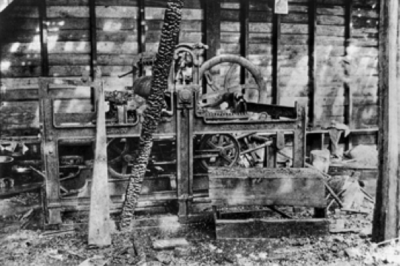

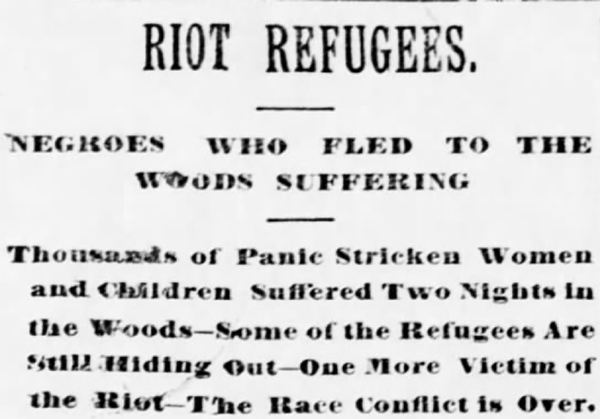

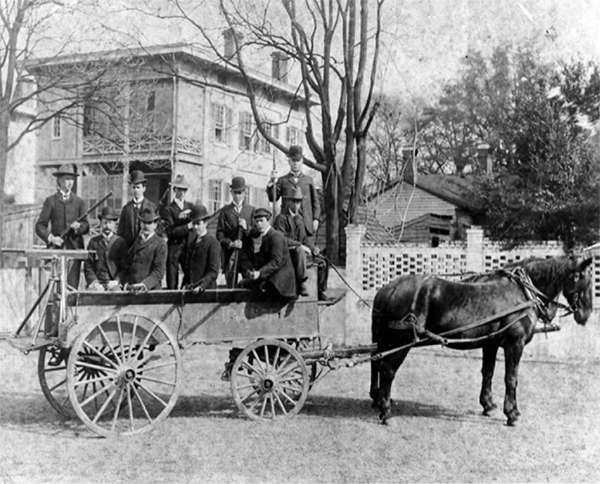

That attack unfolded on election day, November 10th, 1898. It included the only coup d’etat in American history, as the city’s elected officials were violently forced out and replaced by hand-picked white supremacist leaders. It also featured the massacre, an orgy of violence targeting the city’s African-American community. White supremacist militias traveled from around the state to take part in the attacks, bringing with them, among many other weapons, a Gatling gun that rolled through town on a cart firing indiscriminately. By the time the day was done they had burned down the Daily Record and many other buildings, killed hundreds of African-American residents and injured many more, and essentially destroyed the city’s black community for generations. The newly installed white supremacist “Revolutionary Mayor,” Alfred Waddell, would two weeks later write a story for Collier’s Magazine, designating the event a “race riot” and blaming its violence on a mythical African-American mobs and its supporters.

Both those horrific histories and that media misrepresentation inspired Charles Chesnutt to write a novel about the massacre. Set in the fictionalized city of Wellington, Chesnutt’s sweeping historical novel depicts many elements of the late 19th century South and nation, including the aftermath of slavery and the Civil War, the rise of both the KKK and Jim Crow segregation, the lynching epidemic, and life for mixed-race individuals in a society organized so thoroughly around the color line. But the novel builds to a multi-chapter depiction of the massacre and coup, a bracing portrayal that delves into the heart of that day’s violence and ends with one of the bleakest and most biting sentences in American literature. The white supremacist mob has burned down the city’s African American hospital, and Chesnutt’s narrator observes, “The flames soon completed their work, and this handsome structure, … a promise of good things for the future of the city, lay smoldering in ruins, a melancholy witness to the fact that our boasted civilization is but a thin veneer, which cracks and scales off at the first impact of primal passions.”

No line could better sum up the worst of American history, exemplified by Wilmington but present in so many moments. Yet Chesnutt does not end his novel there, and instead creates a pair of final chapters that offers an example of critical optimism in the face of these horrors. Without spoiling all of their details (this is a novel that all Americans should read, now more than ever), I will note that Chesnutt puts two of his central African-American protagonists in a position to exact a small but significant moment of justice and retribution for the day’s and their society’s brutalities, one that they have deeply personal reason to desire. Yet that deserved justice would target a white infant, innocent of all these horrors and a potent symbol of the uncertain future facing the city and the nation. And the two characters choose instead to be closer to the ideals — national, spiritual, human — that their white counterparts have so thoroughly forgotten.

As the novel closes, it seems likely but not inevitable that this moment of critical optimism will succeed, that the infant will live, that a better future than this horrific present remains possible. The novel’s final line is, “There’s time enough, but none to spare.” Here in February 2020, I can’t imagine a more important pair of lessons than those provided by Charles Chesnutt and The Marrow of Tradition: the desperate need to confront the worst of our histories, of what white supremacy has been and done and remains in America; and the equally urgent possibility of seeking a better future, not despite but through and beyond our histories. Now more than ever, we need the critical optimism of this vital American novel.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

PS. For more on all things Wilmington, Chesnutt, and more, see Margaret Mulrooney’s great book, *Race, Place, and Memory: Deep Currents in Wilmington, North Carolina*:

https://mmulrooney.net/my-new-book/

Ben