The Voting Rights Act: Passed, but Present

The Department of Justice called it “the single most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by Congress.” It’s played a role in 22 Supreme Court cases. It’s been subject to five major amendments since it originally passed. And yet, there are still those that would try to undermine it. It is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and it has proven absolutely essential to the advancement of the country.

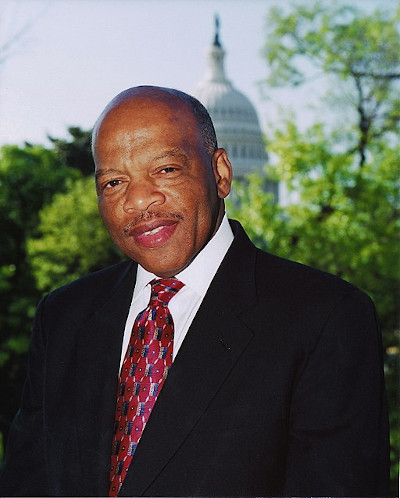

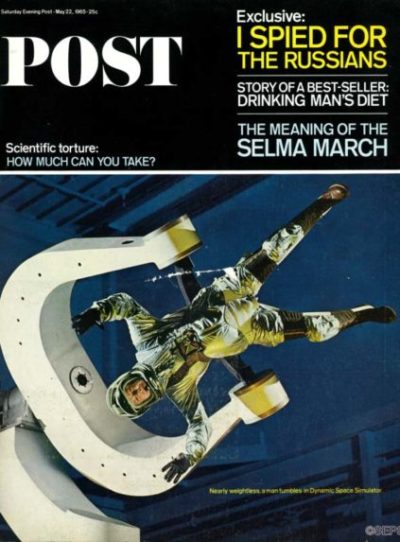

Writ large, the Voting Rights Act is there to prevent racial discrimination against voters. It was signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson 55 years ago this week after a particularly contentious and violent few months in America. March of 1965 saw the marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, three events that The Saturday Evening Post covered at the time. The recently deceased Congressman John Lewis led the first march, an occasion that would be become known as “Bloody Sunday,” after many marchers were attacked by police. President Johnson had called for voting rights action in February, but the focus that the marches put on the issue enabled Johnson to push for such legislation during a televised address to Congress on March 15.

Voting rights had been enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and solidified for all citizens by the so-called Reconstruction Amendments (the 13th, 14th, and 15th). These three amendments also carry language that allows Congress to pass further legislation in the future, should the need arise to provide additional enforcement. The appropriately named Enforcement Acts followed in 1870, making it a criminal offense to interfere with voting rights while also establishing federal oversight for voter registration and elections. However, two Supreme Court decisions in 1875 defanged the Enforcement Acts, meaning that while these new rules were on the books, they were not uniformly interpreted or enforced throughout the country.

After the advent of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s, Congress would pass three sets of legislation aimed at leveling the playing field in America. Civil rights acts passed in 1957, 1960, and 1964. The broad aim of the 1964 Act was to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places . However, there weren’t enough specifics on voting protections. After the election of 1964, Johnson directed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to write a functionally bulletproof act on voting rights; Katzenbach would get input from both Senator Mike Mansfield, the Democratic majority leader, and Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican minority leader. Mansfield and Dirksen jointly sponsored the Act, and introduced it on March 17, 1965. For his part, Dirksen had been moved to co-sponsor the bill after seeing the violence unfold on Bloody Sunday.

When the bill was formally introduced, a total of 64 more Senators joined as co-sponsors. The House and Senate voted on the Act on August 3 and 4, respectively. It passed the House 328-74, and did the same in the Senate 79-18. Two days later, Johnson signed it into law.

The Act covers two sets of provisions; one set is general, which covers the entire country, and the others are “special,” designated for particular states and local government structures. The Act specifically prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or the spoken language of the voter. Literacy tests, once used in many states to disqualify voters, were banned under Section 2. Section 5 targeted areas that were notorious for a history of illegally disenfranchising voters by specifically noting that they couldn’t make changes to law that countermanded any part of the Act without federal consent.

Of course, very few laws or acts are perfect on the first go-round, so amendments have been applied in subsequent acts. The 1970 and 1975 Acts bolstered discrimination protections for voters with language issues. The biggest 1982 change made it easier to determine if discrimination had happened not just in person, but by the wording used in state laws. The Voting Rights Language Assistance Act of 1992 extended protections that were to expire and expanded support for bilingual voters, including Native Americans. The 2006 Act, properly called the Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006, extended the special provisions for another 25 years.

If there’s a battleground for the Act in the future, it’s likely on the field of gerrymandering; in fact, the Act has already figured into Supreme Court decisions on the topic. Sections 2 and 5 forbid the creation of voting districts that are made in such a way as to intentionally split up the votes of minorities protected by the Act. However, the Supreme Court has held that you also can’t draw districts to favor particular racial composition. It’s a balancing act that will likely result in more challenges going forward.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented an important step in the United States. Whether or not it was perfect is beside the point. It was attempt to, for lack of a better phrase, get it right. The great contradiction of America is that it rose under the specter of slavery and has to contend with a Constitution that once called Black people 3/5 of a person. The Act itself represented a long overdue shift, a change that attempted to acknowledge and redress systemic problems in the country. While it’s certain that we have many miles to go, the Act remains a crucial lever in the machine of positive change.

Featured image: President Johnson gave Martin Luther King, Jr. one of the pens used to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Photo by Yoichi Okamoto; Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum. Image Serial Number: A1030-17a. Public Domain.)

5 Ways Your Vote Might Not Count

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was meant to break down obstacles to voter registration that had kept minority groups out of the polls for most of American history. Besides outlawing literacy tests, the act allowed the U.S. attorney general to investigate poll taxes, which had been banned for federal elections in 1964, and state elections in 1966. Section 5 of the act required federal oversight of 11 states where at least 50 percent of the non-white population was not registered to vote.

The Voting Rights Act was seen as a major victory of the civil rights movement and was considered a breakthrough in making sure every citizen had access to one of their most basic rights.

Half a century later, having a voice in American government is not as simple as showing up to the polls on election day. Here are five reasons your political voice may go unheard.

1. Use-it-or-lose-it Registration Laws

It’s impossible for your vote to count if you never get to cast it. Some states have instituted strict registration laws that make it harder for potential voters to stay registered. One example is Ohio’s “use-it-or-lose-it” law that allows the state to unregister voters who have not cast a ballot in a set amount of time. If you go two years without voting the state sends you a warning in the form of a post card. If you go a further four years (missing one presidential election) without responding or voting, the state removes you from voter rolls.

This law was upheld by the Supreme Court case Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute in 2017. It has contributed to the removal of two million voters between 2011 and 2016. And, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissenting opinion, “has disproportionately affected minority, low-income, disabled, and veteran voters.”

2. Exact Match System

The exact match system also presents an obstacle in voter registration. This Georgia law requires the name on your ID to exactly match the name on your registration form. Using “Jim” on the form and having “James” on your ID, for example, would result in disqualification. Even one hyphen or letter out of place will prevent you from voting.

Critics of this system also argue that the exact match system unfairly affects communities of color, as their names would be less familiar to workers entering names into voter registration systems. As such the exact match system has come to be known as “disenfranchisement by typo.”

3. Mailing Address Required

North Dakota requires a current street address as voter identification. This policy prevents voters without a residential street address from registering to vote.

More specifically, most Native Americans living on reservations, (more than 18,000 in North Dakota), use P.O. boxes instead of residential addresses. The policy dictates that the address must be a street address and does not accept P.O. boxes, keeping those living on reservations from the polls. The Supreme Court upheld this law in 2018.

4. Felons Can’t Vote

All but two states (Maine and Vermont) revoke your right to vote upon conviction of a felony. In 14 states and Washington, D.C., this right is automatically restored upon release. In 22 states the right to vote is restored after a waiting period, completion of parole, or independent action of voters. The remaining 12 states require further action to restore the right (such as longer waiting periods or a governor’s pardon) and for some crimes the right to vote is never restored.

In 2018 Florida passed a law that would restore the right to vote to former felons who have already paid their debt the society. This law gave voting rights to 1.4 million people, the largest mass enfranchisement since the Voting Rights Act. This brief moment of victory was quickly followed with a law passed in May of 2019 that required all former felons to pay off back fines and fees to the court before they can vote again. Similar laws exist in four other states, and three states require former felons to personally apply to state legislatures for their voting right to be restored (Arizona requires this only for second-time offenders).

5. Finding a Polling Place

The Voting Right Act’s Section 4 was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2013. The Shelby County v. Holder decision stated that times have changed and states with a long history of voter suppression no longer needed voting policies monitored by the Attorney General or a Washington, D.C. district court. A 2016 study by the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that “Out of the 381 counties [formerly under federal supervision], 165 of them — 43 percent — have reduced voting locations.” At the time of the study, 868 polling locations had closed across the previously monitored states. The closures have continued since 2016.

In Georgia, specifically, over 200 polling places have closed in recent years. The Leadership Conference study claims that the lack of polling places and early voting locations “place[s] an undue burden on minority voters, who may be less likely to have access to public transportation or vehicles, given continuing disparities in socioeconomic resources.”

Voting is much more complicated than simply showing up. The Voting Rights Act aimed to include more Americans in the political discussion. but there is still more that needs to be done. As Lyndon B. Johnson said when introducing the Voting Rights Act “There is no moral issue. It is wrong–deadly wrong–to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country.”

Featured image: Shutterstock