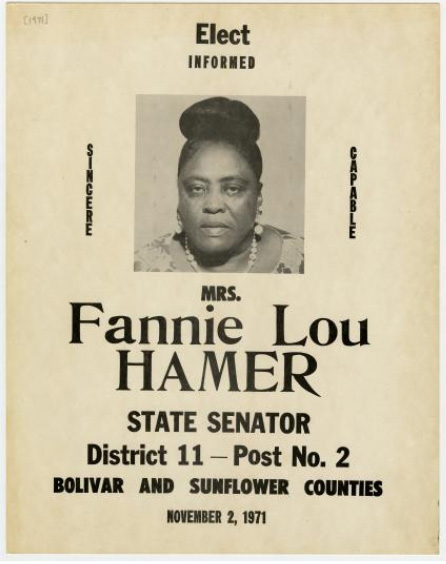

Fannie Lou Hamer’s War on Voter Suppression

Lyndon B. Johnson was distressed a few days before the start of the 1964 Democratic National Convention. In a presentation to the party’s Credentials Committee in an Atlantic City hotel ballroom, a Black Mississippi woman named Fannie Lou Hamer was giving a disturbing account of her various past attempts to exercise her right to vote. She was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Hamer, then 46 years old, had been the youngest of 20 children in her family, leaving school in sixth grade to work on Mississippi plantations. She had been poor her entire life, and suffered from polio as a young girl. Just three years earlier, she had been sterilized against her will while hospitalized for a minor surgery. But her address to the 108 committee members that day recounted, in sickening detail, numerous instances of violent institutional repression that had prohibited Hamer from participating in her country’s — and the Democratic Party’s — democratic process.

She first failed the arcane and discriminatory literacy test that was administered to African Americans in 1962. Then, she was on a busload of hopeful Black voters that was pulled over for being the wrong color (too yellow). Then, the plantation owner kicked her off the land she sharecropped (for attempting to register to vote). Then, in 1963, she was arrested with several others after attending a voter registration workshop. While in jail, she was brutally beaten with a blackjack by other prisoners at the orders of a state trooper who told them to, according to this magazine, “Make the bitch wish she was dead.”

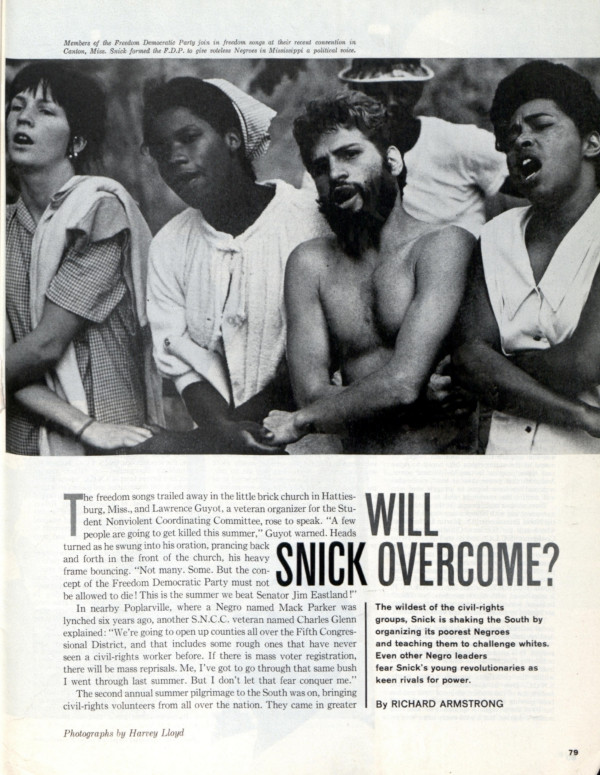

At the Democratic Convention, Hamer was speaking on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a grassroots political project that aimed to replace the state’s elected delegation on the premise that it was illegally selected with a segregated vote — a “white primary.” Less than seven percent of eligible Black adults were registered to vote in Mississippi in 1964. With the cooperation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC or “Snick”), NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Congress of Racial Equality, activists in the South organized tens of thousands of mostly Black, poor and working-class people in a precinct-level effort to subvert the all-white Democratic stronghold in the state.

President Johnson worried that the MFDP — and a potential interracial delegation — would alienate the South’s white Democratic voters, sending them into the arms of the Republicans. During Hamer’s speech, he called an impromptu press conference, leading many to think he was about to announce his running mate. Instead, he gave a commemoration of President Kennedy, who had been assassinated nine months earlier. The television networks still played Hamer’s speech, though, during their primetime broadcasts. Their viewers saw the poor Black sharecropper’s impassioned indictment of her country: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

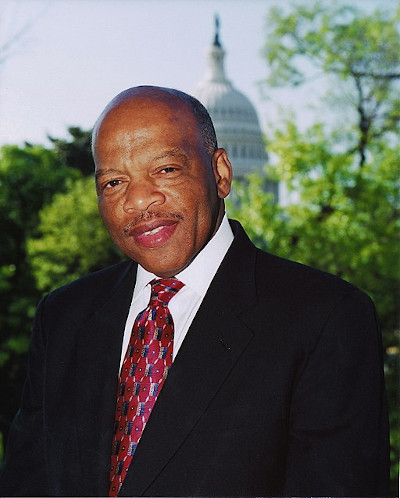

Hamer’s testimony was an uncomfortable dose of reality for liberal America. Even today, her story teaches largely unexamined lessons regarding the background work of the civil rights movement and its many proponents. As scholar Maegan Parker Brooks wrote in her recent biography of Hamer, “The life story of a disabled, impoverished, middle-aged black woman from the rural Mississippi Delta challenges widespread perceptions of who participated in — as well as how they influenced — mid-twentieth century movements for social, political, and economic change.” Hamer is not a household name like Martin Luther King, Jr. or John Lewis, but her role in this transformational period of American history shows us what was at stake, and indeed still is.

Hamer didn’t appear at the 1964 Democratic National Convention out of thin air. Along with three other Black candidates in the state, she ran a primary campaign against the longtime Mississippi representative Jamie Whitten. The Freedom Democrats had been working since the previous fall to both register Black Mississippians and hold straw votes in their own “freedom-registration books” to show what electoral participation could look like in the state where African Americans made up 42 percent of the population. That summer, a profile of Hamer in The Nation posited that “The wide range of Negro participation will show that the problem in Mississippi is not Negro apathy, but discrimination and fear of physical and economic reprisals for attempting to register.”

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, the civil rights groups that made up the Council of Federated Organizations undertook a statewide organizing effort to account for Black non-voters and register as many as possible. They also established Freedom Schools, community centers, and a Freedom Labor Union. At the heart of this undertaking was the oversized contribution of SNCC, the activist group Hamer had worked with diligently since attending a mass meeting in 1962. Hamer traveled around the state, stirring Black audiences with speeches that motivated them to act for their own liberation. (“It’s a shame before God that people will let hate not only destroy us, but it will destroy them. Because a house divided against itself cannot stand and today America is divided against itself because they don’t want us to have even the ballot here in Mississippi.”) At the same time, SNCC’s army of volunteers — largely white college students from the North — were moving around Mississippi organizing for participatory democracy at every level.

In 1965, this magazine covered the student group (“Will Snick Overcome?”), pointing out the markedly more radical approach SNCC employed compared to a group like the NAACP. Arising from the sit-ins of 1960, SNCC was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and decidedly non-hierarchical. While it claimed manpower from the country’s college students, SNCC aimed to cultivate leadership at the community level in its campaigns. The Post recognized this unique tactic of SNCC’s “shock troops,” even if it seemed tedious: “The whole concept of building a political force out of tenant farmers, slum-dwellers and the unemployed is a radical departure from American political norms.”

In response to claims that communists and Marxists — perhaps even foreign ones — were stirring up all of the trouble in the South, Hamer gave a simple response in a speech at a mass meeting in 1964: “People will go different places and say, ‘The Negroes, until the outside agitators came in, was satisfied.’ But I’ve been dissatisfied ever since I was six years old.” Hamer’s lifelong dissatisfaction steered her toward a fight for voter enfranchisement, and later, as Brooks puts it in her biography, fights “against white supremacy, police brutality, sexual assault, segregated education, food insecurity, and health care access” among others.

In June, before the convention, three Freedom Summer organizers — James Earl Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman — were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The Ku Klux Klan had grown its numbers in the area and burned down 20 black churches that summer, many of which were hubs for civil rights activity. The three men had been involved with a church that housed a Freedom School, and several Klansmen, policemen, and a minister conspired to shoot them and hide their bodies. The case was a national outrage, but over the course of the federal investigation eight bodies of Black men were found, several of them civil rights workers as well.

After Hamer made the MFDP’s case to the Credentials Committee at the convention, the Johnson administration countered with a negotiation offer: the MFDP could have two at-large seats (picked by Johnson) without unseating any of the Mississippi delegation, and the party would ban segregated delegations in 1968. Hamer and other Freedom delegates were fuming at the prospect of accepting such a paltry deal, but leaders from the NAACP and SCLC, including Martin Luther King, Jr., advised them to take it. The MFDP unanimously voted against accepting the offer, in an outright rejection of the legitimacy of the Mississippi delegation.

That repudiation is an important aspect of Hamer’s legacy in that it refuses to conform to what author Jeanne Theoharis calls the “national fable” of the civil rights movement: the idea that this era of our history can be represented as a settled legislative triumph featuring a small cast of iconic heroes instead of as a disruptive, radical mass movement against institutional white supremacy. Hamer was not interested in a reassuring narrative for white folks; she wanted liberation.

The next month, Harry Belafonte took a group from the MFDP — including John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer — on a trip to Guinea. They were received with a warm welcome, meeting President Ahmed Sékou Touré and touring his palace. On the trip, Hamer wrote in her autobiography, she felt she was treated much better in Africa than in America, and she noticed many of the negative stereotypes she had been led to believe about Africans were incorrect. “So when they say, ‘Go back to Africa,’” she wrote, “I say, ‘When you send the Polish back to Poland, the Italians back to Italy, the Irish back to Ireland and you get on that Mayflower from whence you came and give the Indians their land back.’ It’s our right to stay here and we stay and fight for what belongs to us.”

Featured Image Courtesy of the Archives and Records Services Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The Voting Rights Act: Passed, but Present

The Department of Justice called it “the single most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by Congress.” It’s played a role in 22 Supreme Court cases. It’s been subject to five major amendments since it originally passed. And yet, there are still those that would try to undermine it. It is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and it has proven absolutely essential to the advancement of the country.

Writ large, the Voting Rights Act is there to prevent racial discrimination against voters. It was signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson 55 years ago this week after a particularly contentious and violent few months in America. March of 1965 saw the marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, three events that The Saturday Evening Post covered at the time. The recently deceased Congressman John Lewis led the first march, an occasion that would be become known as “Bloody Sunday,” after many marchers were attacked by police. President Johnson had called for voting rights action in February, but the focus that the marches put on the issue enabled Johnson to push for such legislation during a televised address to Congress on March 15.

Voting rights had been enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and solidified for all citizens by the so-called Reconstruction Amendments (the 13th, 14th, and 15th). These three amendments also carry language that allows Congress to pass further legislation in the future, should the need arise to provide additional enforcement. The appropriately named Enforcement Acts followed in 1870, making it a criminal offense to interfere with voting rights while also establishing federal oversight for voter registration and elections. However, two Supreme Court decisions in 1875 defanged the Enforcement Acts, meaning that while these new rules were on the books, they were not uniformly interpreted or enforced throughout the country.

After the advent of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s, Congress would pass three sets of legislation aimed at leveling the playing field in America. Civil rights acts passed in 1957, 1960, and 1964. The broad aim of the 1964 Act was to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places . However, there weren’t enough specifics on voting protections. After the election of 1964, Johnson directed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to write a functionally bulletproof act on voting rights; Katzenbach would get input from both Senator Mike Mansfield, the Democratic majority leader, and Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican minority leader. Mansfield and Dirksen jointly sponsored the Act, and introduced it on March 17, 1965. For his part, Dirksen had been moved to co-sponsor the bill after seeing the violence unfold on Bloody Sunday.

When the bill was formally introduced, a total of 64 more Senators joined as co-sponsors. The House and Senate voted on the Act on August 3 and 4, respectively. It passed the House 328-74, and did the same in the Senate 79-18. Two days later, Johnson signed it into law.

The Act covers two sets of provisions; one set is general, which covers the entire country, and the others are “special,” designated for particular states and local government structures. The Act specifically prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or the spoken language of the voter. Literacy tests, once used in many states to disqualify voters, were banned under Section 2. Section 5 targeted areas that were notorious for a history of illegally disenfranchising voters by specifically noting that they couldn’t make changes to law that countermanded any part of the Act without federal consent.

Of course, very few laws or acts are perfect on the first go-round, so amendments have been applied in subsequent acts. The 1970 and 1975 Acts bolstered discrimination protections for voters with language issues. The biggest 1982 change made it easier to determine if discrimination had happened not just in person, but by the wording used in state laws. The Voting Rights Language Assistance Act of 1992 extended protections that were to expire and expanded support for bilingual voters, including Native Americans. The 2006 Act, properly called the Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006, extended the special provisions for another 25 years.

If there’s a battleground for the Act in the future, it’s likely on the field of gerrymandering; in fact, the Act has already figured into Supreme Court decisions on the topic. Sections 2 and 5 forbid the creation of voting districts that are made in such a way as to intentionally split up the votes of minorities protected by the Act. However, the Supreme Court has held that you also can’t draw districts to favor particular racial composition. It’s a balancing act that will likely result in more challenges going forward.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented an important step in the United States. Whether or not it was perfect is beside the point. It was attempt to, for lack of a better phrase, get it right. The great contradiction of America is that it rose under the specter of slavery and has to contend with a Constitution that once called Black people 3/5 of a person. The Act itself represented a long overdue shift, a change that attempted to acknowledge and redress systemic problems in the country. While it’s certain that we have many miles to go, the Act remains a crucial lever in the machine of positive change.

Featured image: President Johnson gave Martin Luther King, Jr. one of the pens used to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Photo by Yoichi Okamoto; Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum. Image Serial Number: A1030-17a. Public Domain.)

5 Ways Your Vote Might Not Count

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was meant to break down obstacles to voter registration that had kept minority groups out of the polls for most of American history. Besides outlawing literacy tests, the act allowed the U.S. attorney general to investigate poll taxes, which had been banned for federal elections in 1964, and state elections in 1966. Section 5 of the act required federal oversight of 11 states where at least 50 percent of the non-white population was not registered to vote.

The Voting Rights Act was seen as a major victory of the civil rights movement and was considered a breakthrough in making sure every citizen had access to one of their most basic rights.

Half a century later, having a voice in American government is not as simple as showing up to the polls on election day. Here are five reasons your political voice may go unheard.

1. Use-it-or-lose-it Registration Laws

It’s impossible for your vote to count if you never get to cast it. Some states have instituted strict registration laws that make it harder for potential voters to stay registered. One example is Ohio’s “use-it-or-lose-it” law that allows the state to unregister voters who have not cast a ballot in a set amount of time. If you go two years without voting the state sends you a warning in the form of a post card. If you go a further four years (missing one presidential election) without responding or voting, the state removes you from voter rolls.

This law was upheld by the Supreme Court case Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute in 2017. It has contributed to the removal of two million voters between 2011 and 2016. And, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissenting opinion, “has disproportionately affected minority, low-income, disabled, and veteran voters.”

2. Exact Match System

The exact match system also presents an obstacle in voter registration. This Georgia law requires the name on your ID to exactly match the name on your registration form. Using “Jim” on the form and having “James” on your ID, for example, would result in disqualification. Even one hyphen or letter out of place will prevent you from voting.

Critics of this system also argue that the exact match system unfairly affects communities of color, as their names would be less familiar to workers entering names into voter registration systems. As such the exact match system has come to be known as “disenfranchisement by typo.”

3. Mailing Address Required

North Dakota requires a current street address as voter identification. This policy prevents voters without a residential street address from registering to vote.

More specifically, most Native Americans living on reservations, (more than 18,000 in North Dakota), use P.O. boxes instead of residential addresses. The policy dictates that the address must be a street address and does not accept P.O. boxes, keeping those living on reservations from the polls. The Supreme Court upheld this law in 2018.

4. Felons Can’t Vote

All but two states (Maine and Vermont) revoke your right to vote upon conviction of a felony. In 14 states and Washington, D.C., this right is automatically restored upon release. In 22 states the right to vote is restored after a waiting period, completion of parole, or independent action of voters. The remaining 12 states require further action to restore the right (such as longer waiting periods or a governor’s pardon) and for some crimes the right to vote is never restored.

In 2018 Florida passed a law that would restore the right to vote to former felons who have already paid their debt the society. This law gave voting rights to 1.4 million people, the largest mass enfranchisement since the Voting Rights Act. This brief moment of victory was quickly followed with a law passed in May of 2019 that required all former felons to pay off back fines and fees to the court before they can vote again. Similar laws exist in four other states, and three states require former felons to personally apply to state legislatures for their voting right to be restored (Arizona requires this only for second-time offenders).

5. Finding a Polling Place

The Voting Right Act’s Section 4 was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2013. The Shelby County v. Holder decision stated that times have changed and states with a long history of voter suppression no longer needed voting policies monitored by the Attorney General or a Washington, D.C. district court. A 2016 study by the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that “Out of the 381 counties [formerly under federal supervision], 165 of them — 43 percent — have reduced voting locations.” At the time of the study, 868 polling locations had closed across the previously monitored states. The closures have continued since 2016.

In Georgia, specifically, over 200 polling places have closed in recent years. The Leadership Conference study claims that the lack of polling places and early voting locations “place[s] an undue burden on minority voters, who may be less likely to have access to public transportation or vehicles, given continuing disparities in socioeconomic resources.”

Voting is much more complicated than simply showing up. The Voting Rights Act aimed to include more Americans in the political discussion. but there is still more that needs to be done. As Lyndon B. Johnson said when introducing the Voting Rights Act “There is no moral issue. It is wrong–deadly wrong–to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country.”

Featured image: Shutterstock