Are You Barred from the Polls by Obsolete Law?

In this 1960 editorial, the Post urged states to eliminate stringent residency requirements and other rules that disenfranchised voters.

Our ridiculously outdated state voting laws are responsible for a mass disfranchisement of 13 percent of the nation’s total potential voting force.

When these laws were enacted, many of them a century and more ago, we were a less mobile people, and there was perhaps justification for requiring a person to live within the state for one and even two full years before being eligible to vote — as most states still do. But in these days of frequent job transfers and family moves, such waiting periods are far too long.

Similarly there is no valid reason why an otherwise qualified voter should forfeit his ballot simply because he has the misfortune to be incapacitated or must make an urgent business trip on Election Day. Yet most states have no provisions for balloting in such emergency situations. Help must be extended to those voters who want to do their civic duty and can’t.

—“Are You Barred from the Polls by Obsolete Law?,” Editorial, November 12, 1960

This article is featured in the November/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Constatin Alajalov / SEPS

Should Uninformed People Be Allowed to Vote?

One of the basic tenets of American government is that all qualified citizens should be able to vote. We trust the American people to make the right choice.

But Americans’ faith in “the people” has been weakened in the past few years. A great division has yawned between the political parties, and it’s not uncommon to hear Americans claim that voters in the other party are just plain ignorant.

There’s no doubt that democratic elections are determined, to a degree, by ill- or uninformed voters — even though our public education system was created to avoid this. A recent poll showed most Americans don’t know basic facts about the Constitution. (A third of respondents couldn’t name a single branch of government or a single right protected by the Bill of Rights.) Even worse, people may be voting based on intentional disinformation.

In our earliest days, Americans limited the vote to a select minority of people deemed as “qualified.” The colonies only allowed men to vote who owned sufficient property and/or belonged to the correct church. After independence, the framers of the Constitution said nothing about who could vote; they left the question up to each state.

All of the new states kept some form of the old colonial restrictions. In New Hampshire, for example, only white males with £50 of personal property could vote. Virginian voters needed 50 acres of vacant land, 25 of cultivated land, and a house measuring 12×12 feet.

These restrictions were intended to create an electorate of presumably educated, responsible men. But the idea clashed with the principle of equality and, in time, voting restrictions eased. But many people were still prevented from voting.

In 1855, Connecticut became the first state to require voters to pass a literacy test. In 1921, New York required new voters to take a test proving they had the equivalent of an eighth-grade education. (About 15 percent flunked.) As late as 1959, the Supreme Court was ruling that such tests didn’t violate the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments.

The problem with literacy tests was that they could be used for political ends. They were used largely to keep African Americans and recent immigrants from voting. At the turn of the century in Mississippi, 60 percent of Black men couldn’t read. But the county clerk was the sole judge of who was literate, and therefore nearly 100 percent of Black voters were denied the right to vote.

Literacy tests persisted until the 1965 Voting Rights Act prohibited the tests in states that had obviously discriminated against Black voters. Not until 1975 were literacy tests finally banned outright by Congress.

Now, almost everyone can vote, but how well-informed is the electorate? Over the years, surveys have tracked the surprisingly low level of voter knowledge. A 2010 survey found a third of respondents couldn’t tell if the Civil War came before or after the War of Independence. And today, one in five adults say they get most of their political news from social media, which often carries deliberate misinformation from domestic or foreign sources.

The chronic need for better educated voters causes an inherent problem in democracies, according to Jennifer Hochschild, professor of government at Harvard. In 2010, she noted all democracies believe informed voters are essential to good government while they continually extend suffrage to greater proportions of their people. But this tends to bring less informed voters into the electorate, which led to her ask, “If democracies need informed voters, how can they thrive while expanding enfranchisement?”

Recently the idea of an epistocracy — government by the knowledgeable — has been making a resurgence. In his book, Against Democracy, Georgetown philosophy professor Jason Brennan justifies the idea by arguing the public has a right to be protected from individuals’ stupid mistakes.

He compares electoral votes to jury votes. If jurors pay no attention during a trial, or assign guilt based on their first impressions, or develop crazy conspiracy theories about the case, or are simply prejudiced against the accused, they’re incapable of rendering an informed verdict. The judge would have the right to declare a mistrial. The same standard should apply to choosing the president.

Brennan says incompetent voters should not exercise power of fellow citizens. If politicians or voters can’t fulfill their civic obligation morally and effectively, they should be barred from office or the voting booth.

His solution would be to test the political knowledge of all voters. Those votes of anyone who passed the test would be counted as two or more votes. Brennan’s test would be drawn up by 500 randomly selected citizens.

Americans might not appreciate people with a better-than-average-knowledge of government having a louder voice in an election. Citizens who’ve enjoyed a privileged life and the benefit of a good education would outweigh the will of the disadvantaged. And voters who don’t pass the test would naturally assume the test-passers were throwing their weight behind the laws and politicians who would benefit themselves.

Fortunately, democracy — even with its ignorant voters — works better than expected. Economist Amartya Sen points out that democracies have the most stable form of government and never have famines. Other researchers have found democracies generally work to avoid conflict and are less likely to wage war with other democracies. They have less civil conflict, less terrorism, and fewer attacks against women.

And, according to Professor Hochschild, voters aren’t as ignorant as they’re presented. They may not know the workings of legislation, but they are knowledgeable on issues that are important to them. In considering an incumbent presidential candidate, they can always ask themselves if they are better or worse off than four years earlier. Experience can fill in gaps in education; voters learn election by election.

Most importantly, unequal representation is contrary to the very foundations of American democracy. As John R. Allen of the Brookings Institution put it, “The United States is grounded upon the idea that individuals are owed the equal opportunity to voice their opinion as we, through our elected officials, chart the course of our nation. This idea is foundational to our American values and informs a great deal about what it means to be a citizen of the United States.”

Democracy isn’t easy; it requires more attention and thought than many are ready to give it. President Kennedy believed voters should be far better informed, since, as he said, “the ignorance of one voter in a democracy impairs the security of all.”

But Winston Churchill was willing to accept democracy, and voters, as they were. After all, he said, “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried.”

Featured image: roibu / Shutterstock

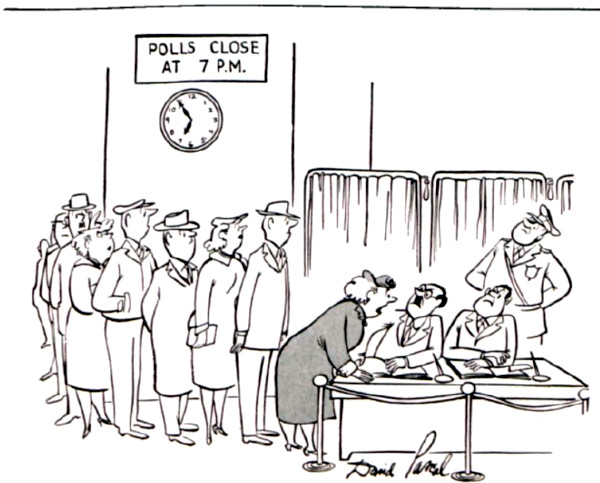

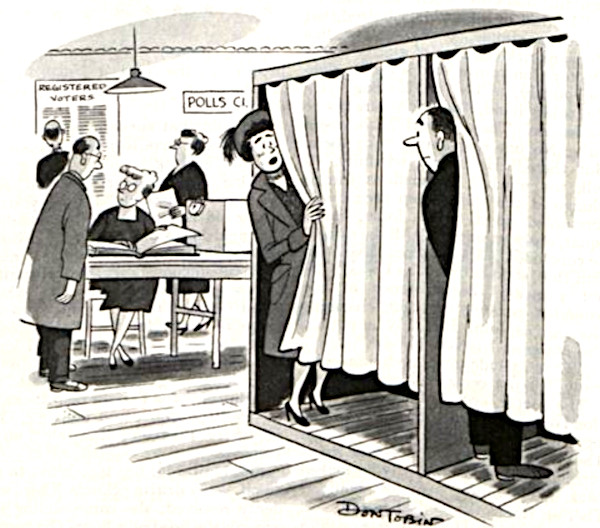

Cartoons: Election Time

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

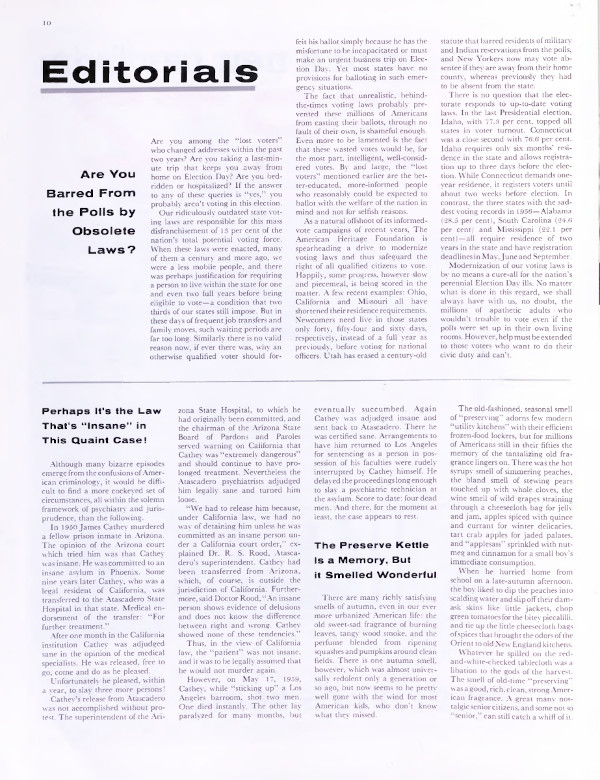

Jeff Keate

October 7, 1944

Bill King

September 13, 1952

Hoff

July 12, 1952

Richter

March 15, 1952

Stan Hunt

December 8, 1951

Clyde Lamb

December 1, 1951

David Pascal

November 5, 1955

Don Tobin

November 4, 1950

Mary Gibson

November 4, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

How Much Does Your Vote Weigh?

In 1916, the election was decided by just 3.1 percent of the popular vote.

John F. Kennedy won the presidency by just 0.2 percent.

And in 2000 the presidency was ultimately decided by just 537 votes.

In the next election, you might be among the handful of voters who decides an election.

Theoretically, your vote for the president has the same impact as any of the other 227,000,000 qualified voters in the U.S. And the candidate with the most votes would win.

But the electoral college changes the weight of your vote depending on where you live. And it can give the presidency to the candidate who may have lost the popular vote.

The last time a candidate won popular vote but lost the electoral college vote was 2016, but it wasn’t the only time. It has occurred 5 times before in our history.

When the electoral college was created in 1787, it was originally intended to balance the electoral power so that Americans in sparsely populated areas weren’t outvoted by the people in the cities. At the time, most Americans were living in rural areas; reducing the electoral power of urban voters would have a limited effect.

Today, the urban/rural division in the population is 80/20, but that rural minority has considerable clout in Washington. After the September 11 attacks, for example, Wyoming received seven times as much Homeland-Security money per capita as New York.

Each state has a set number of electoral votes based on its population. With two exceptions — Maine and Nebraska — the candidate who wins the majority of each state’s popular votes is awarded all of the state’s electoral votes. So within your state, your vote has the same weight as any other voter.

But your electoral college impact depends on your state. Wyoming, for instance, with the lowest population (589,000), has three electoral votes. California, with its population of 39,144,818, has 55.

However, the states’ electoral votes aren’t determined by a uniform calculation. Based on 2016’s returns, Wyoming’s electoral votes were drawn from 586,107 residents, or one electoral vote per 195,369 voters. But California’s electoral votes worked out to one electoral vote for 711,723 voters.

You could say that a Wyoming voter had 3.6 times the weight of a California voter.

This is the most extreme example. But if you do the same math to compare the ten most populous and then least populous states, you’ll find their relative electoral weight is a ratio of 1 (most populous) to 2.5 (least populous).

This fact has led to assertions that voters in low-population states have an undue influence in national politics.

But Dale Durran says this isn’t the only distortion of the representative vote. In an article for theconversation.com, the University of Washington mathematics professor found another factor that will affect your vote’s weight.

He divided the total number of America’s electoral votes — 538 — by the 136 million votes cast in 2016 election. The result was the electoral weight of an average vote: one four-millionth of an electoral vote. But this number, as we’ve seen, is altered by the electoral college. And, he finds, it is also altered by the number of ballots cast within a state. Since the electoral votes are fixed for each state, the weight of each ballot diminishes slightly as more ballots are cast.

If you calculate the electoral college weight of each vote with the voter turnout in the state, Wyoming voters still have the greatest weight (2.97), followed the District of Columbia (2.45), and Vermont (2.42). Florida voters had the least weight: 0.78.

Durran illustrates the point with two states — Oklahoma and Oregon — which have the same number of electoral votes. Because fewer Oklahomans cast their ballots (52 percent) than Oregonians (66 percent), an Oklahoma voter had a weight of 1.22 while an Oregon voter has only 0.89.

His analysis shows that your location can raise the weight of your vote, aside from its electoral college value. The impact of these small numbers of votes in battleground states can make a big difference in who gets elected.

Durran identifies five key states where the 2016 race was close. The electoral votes in four of the states —Wisconsin (10 electoral votes), Michigan (16), Pennsylvania (20), and Florida (29) — were decided by just one percent of the votes.

And these were states whose votes had an electoral college weight of less than 0.85. This means, for instance, that fewer than 27,000 Wisconsin voters decided who got their states’ electoral votes.

If you live in one of these states, your vote may not have the same weight in the electoral college as someone from Wyoming or D.C. But Durran’s analysis shows that a relatively small number of people can make a big difference in the outcome of an election.

So if you decide to stay home on election day, you’re not only giving up your vote, but you’re also conferring additional voting power to another voter – one whose interests and values might be at odds with yours. Even if the math shows your vote doesn’t count quite as much as someone’s else, it’s still your country, and your voice, and your chance to make a difference. So vote.

Featured image: hafakot / Shutterstock

Stuck in a Long Line to Vote? It Could Be Worse.

If you’re stuck in a long voting line today — hungry, tired, feet aching— consider what some voters in the rural West had to endure to vote in the 1946 election.

Considering History: The Fight for Native American Citizenship and Voting Rights

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Native American issues and identities have taken center stage in our political conversations over the last two weeks. On October 9, the Supreme Court issued a last-minute ruling upholding North Dakota’s controversial voter ID act, a law that by requiring voters to have a residential address effectively disenfranchises Native Americans living on the state’s many reservations. And on October 15, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren responded to Donald Trump’s longstanding attacks on her claims to Native American ancestry by releasing the results of a DNA test featuring “strong evidence” of native heritage.

The Warren story has dominated much of these recent political and media conversations. While that story does offer a potential opening for important discussions of how we define Native American identity and community, it also serves as an unfortunate distraction from the unfolding battle over the North Dakota law and what it means for 21st century Native American rights and communities. And this contemporary battle becomes even more meaningful when placed in the context of the complex and contested history of Native American citizenship and voting rights.

These debates over native sovereignty are longstanding and ongoing. To many scholars and activists, Native American tribes exist outside of (and equal to) the United States. Viewed through that lens, Native Americans should, one day, be able to seek dual citizenship from both their tribe as well as from the United States; their voting rights would, therefore, be tied to that legal and political status.

Despite this status, native citizenship has been tenuous and hard-won. The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in June 1866, was a watershed moment in the expansion of American citizenship — but not for Native Americans. While it extended protections to all former slaves and their descendants and enshrined into law the concept of “birthright citizenship” for all those born in the United States, this amendment did not apply to all Americans. As a number of subsequent court cases reiterated, the law defined Native Americans as “wards” of the state instead, leaving them outside of this otherwise all-encompassing revision of the national community.

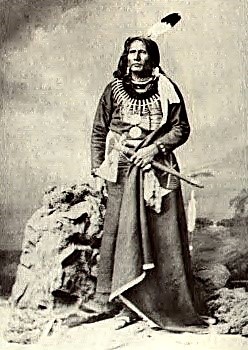

Late 19th century native activists and their allies, however, did not allow this discriminatory exception to go unchallenged. In 1879, Ponca Chief Standing Bear, who had undertaken an extensive protest and speaking tour in order to raise awareness of his tribe’s unlawful and violent treatment at the hands of the U.S. government and military, sued General George Crook. Standing Bear’s suit challenged both the Ponca tribe’s displacement from their Nebraska homeland to an Oklahoma reservation and his personal imprisonment by General Crook (for illegally leaving that reservation in order to stage his protests). After a lengthy and highly public trial, Judge Elmer Dundy ruled in Standing Bear’s favor, noting in his decision that “an Indian is a person” and that “[Indians] have the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

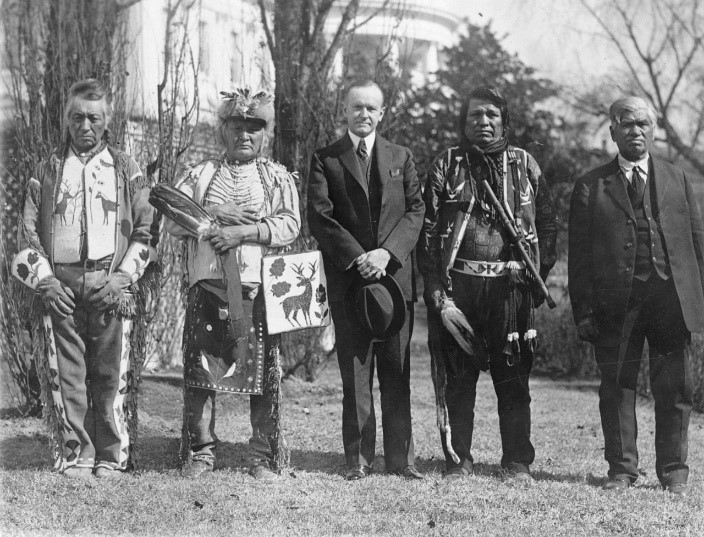

The actions of Chief Standing Bear, along with other victories such as the new (if still circumscribed) opportunities for native citizenship granted by the 1887 Dawes Act, helped push the nation toward a slow, but full recognition of Native American citizenship. This recognition came, mostly, in the form of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, which declared “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States…to be citizens of the United States,” so long as “the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”

Yet as many other groups of Americans throughout our history have long known, full citizenship does not necessarily entail equal voting rights (despite the 15th Amendment’s guarantee that it does). Indeed, through at least the late 1950s, many states maintained laws that prohibited Native Americans from voting. In New Mexico, for example, the state constitution explicitly barred Native Americans living on reservations (the vast majority of the state’s native population) from voting in either state or federal elections. That constitutional discrimination was challenged by native and civil rights activists as early as 1948, but wasn’t amended until 1962.

Even with such changes to state law, coupled with the nationwide protections afforded by the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the battle to ensure and protect Native American voting rights has persisted throughout the 20th century and into the present day. The American Indian Movement (AIM) — too often known only for its controversial occupations and legal cases, such its ongoing fight to free Leonard Peltier from prison — has pursued Standing Bear’s legacy, pushing the struggle for voting rights into our present century. The most recent challenges to the Voting Rights Act and voting access have likewise drastically affected native communities, and are the subject of continued challenges from native activists and their allies, such as the efforts by a number of Arizona tribes to contest that state’s new, labyrinthine Voter ID requirements.

In North Dakota, Arizona, and elsewhere, voting rights and voter suppression efforts have become a central story in the final weeks before the crucial 2018 midterm elections, and rightly so. But the more we can engage with the longstanding debates over and battles for citizenship and civic participation, the more we can recognize the true significance and stakes of these 21st century conflicts.