Considering History: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Urgent Lessons of History

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

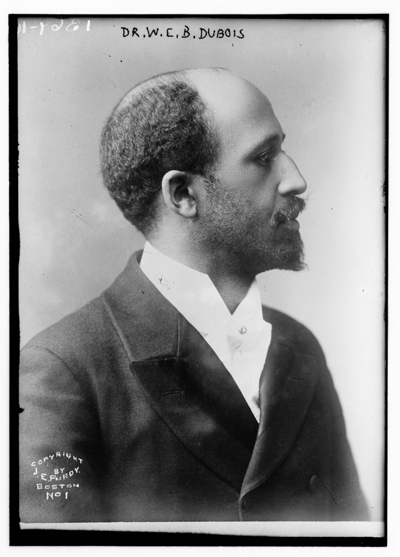

On February 23, 1868, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The only child of mixed-race parents who separated when he was two, Du Bois was raised by his single mother Mary and her parents and family, experiencing this integrated community and school system as one of the town’s only African American residents. He left Great Barrington in 1885 to attend Nashville’s historically black Fisk University, and then pursued further studies at Harvard College, the University of Berlin, and back to Harvard University where he became in 1895 the first African American to receive a PhD (in History). He would spend his remaining seven decades becoming one of America’s and the world’s foremost historians, journalists, educators, writers, activists, and public figures, passing away in Ghana the day before the August 1963 March on Washington.

Those details only scratch the surface of the life, career, and impact of this towering figure, and he rewards further research and reading. But to celebrate the joint occasion of Du Bois’s 151st birthday and the last week of Black History Month, it’s worth taking a step back to consider a few of the many ways that Du Bois’s work and words resonate with our contemporary moment, offering urgent lessons for America and the world in 2019.

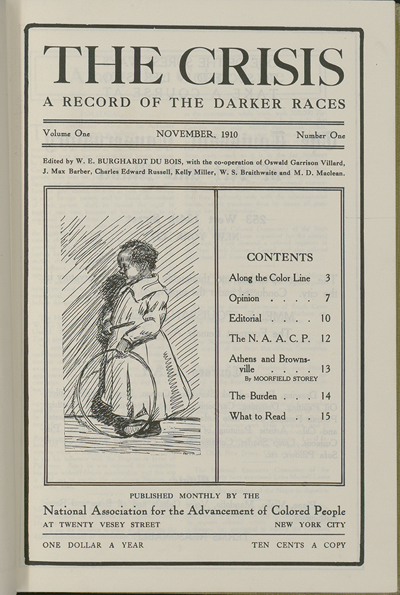

In 1910, Du Bois helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and became its first director of publicity and research. In that role he founded and for many years edited the NAACP’s monthly magazine The Crisis, contributing thoughtful and impassioned editorials on many of the era’s most significant issues. In one such editorial, “Returning Soldiers” (May 1919), Du Bois highlighted the irony of African American World War I veterans returning home to face racist discrimination and violence in the U.S., and advocated for patriotic activism in response to those horrors:

But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land. We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.

All too often, the antiracist protests of Colin Kaepernick, #BlackLivesMatter, and their activist peers are framed in opposition to both the military and American patriotic ideals. Yet so many moments in history, from U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War to Jackie Robinson’s World War II sit-in for military integration, highlight the inescapable interconnections between African American activists, military service, and the nation’s highest ideals and darkest realities. Du Bois’s stirring words help us consider Kaepernick and #BLM as part of this legacy, rather than as critics of it.

In July 1930, Du Bois returned to Great Barrington to give a speech to the Searles High School Alumni Association. He chose to focus on the school’s relationship to the neighboring Housatonic River:

It may be that some thoughtful person saw far beyond the present and grasped the idea that they were putting the institution on what was the natural great highway of the valley. They may have looked forward to the time when parks and boulevards would line the redeemed river; when the best people would not attempt to climb the hills to get away from the valley, but turn about and descend to its gracious invitation; when public buildings and canoes and pleasure boats and swimming children would make the whole valley glad and the river would come into its own again. … With this beginning we may in time clear the river, give the Searles High school its perfect setting. We may even induce the mills (if we can find out who owns them) to stop pouring their refuse into the river, which is merely a habit and not a necessity. … And so I have ventured to call the attention of the graduates of the Searles High School to this bit of philosophy of living in this valley, urging that we should rescue the Housatonic and clean it as we have never in all the years thought before of cleaning it, and seek to restore its ancient beauty; making it the center of a town, of a valley, and perhaps — who knows? — of a new measure of civilized life.

While the environmental movement has evolved significantly over the last few decades, perspectives on environmental activism and justice continue to define this work as separate from our shared human communities and histories. But as Du Bois here reminds his fellow Searles graduates, the story, history, and future of our rivers (and our environment in every sense) are intertwined with those of our schools and our children, our towns and our societies. Such lessons have never been more relevant than in these pivotal remaining years to combat and reverse global climate change.

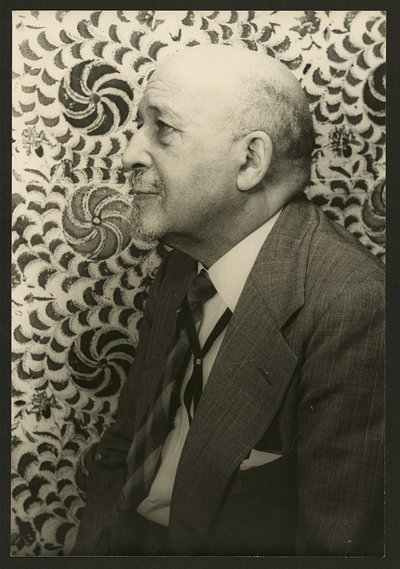

Despite these and many other diverse and deep interests, however, Du Bois was first and foremost a historian. In 1936 he published his best scholarly work, and one of the most ground-breaking and influential historiographic texts in American history: Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. Black Reconstruction influenced both the specific scholarly conversations and the discipline of history in multiple ways, from Du Bois’s archival research process to his challenging and compelling conclusions.

But the book’s stand-out section is its last chapter, “The Propaganda of History,” where Du Bois traces the development (in educational textbooks, academic scholarship, and popular culture) of false and destructive narratives of post-Civil War history. Some of the most damning such narratives were those that depicted African Americans as so ignorant and savage that they thoroughly abused their new freedoms, as illustrated by entirely manufactured images (including a sequence in the 1915 blockbuster film Birth of a Nation) of the first African American elected officials holding raucous and lewd parties on the floors of state legislatures throughout the South. “It is propaganda like this,” Du Bois writes, “that has led men in the past to insist that history is ‘lies agreed upon’; and to point out the danger in such misinformation. It is indeed extremely doubtful if any permanent benefit comes to the world through such action. Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?”

Du Bois’s thorough documentation and debunking of this propagandistic vision of post-Civil War American history is most overtly relevant to our debate over Confederate memorials and memory. Constructed in the early 20th century, the same era in which that Dunning School narrative of Reconstruction was taking hold throughout educational and cultural settings, these Confederate monuments truly represent lies agreed upon, misrepresentations of both the causes and enduring effects of the Civil War and the Confederacy. We have yet to tell the truth about their histories in our collective conversations.

Yet Du Bois’s chapter also makes the case for remembering a nation’s “great and beautiful things,” not in opposition to such dark histories but in direct relationship to them. In the final paragraphs of his magisterial book The Souls of Black Folk (1903), he highlights one such great and beautiful thing: the contribution of African Americans to every stage and element of American identity. There’s no better way to end a commemoration of Du Bois’s birthday and Black History Month than with those stirring concluding worlds: “Our song, our toil, our cheer, and warning have been given to this nation in blood-brotherhood. Are not these gifts worth the giving? Is not this work and striving? Would America have been America without her Negro people?”

Featured image: Library of Congress