Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: 8 Negative Thoughts that Interfere with Weight Loss

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

One of the first steps to changing your thinking is to identify thoughts that get in your way. Categorizing these irrational beliefs can lead to building a shortcut that will help lead to functional thinking and healthier behavior. Here are seven types of negative thinking that can interfere with weight loss.

1. All or Nothing Thinking

Did you go to bed as a late-night snacking bug and hope to awaken in the morning as a die-hard dedicated dieter? Motivation, drive, and excitement can be instrumental in helping us accomplish important goals such as losing weight. But when we look at things in a polarized way, we end up repeating cycles of weight loss and regain.

To learn more about how to combat this pattern of thinking, read Avoid “All or Nothing” Thinking.

2. Filter Focus

Some people filter out accomplishments and focus only on their deficiencies, especially those related to weight. An example would be ignoring the two pounds you lost, while focusing on a package of cookies you ate this morning. This viewpoint leads down a road of frustration and hopelessness, paved with the perceived tragedy of many failures. Don’t get me wrong, we do need to understand and evaluate our mishaps, but only if we also enjoy our positive attributes and success.

Learn how choosing to mainly focus on the positive aspects of life changes your outlook on every situation, the people you encounter, and yourself, in The Problem with Filter Focus.

3. Mind Reading

Mind reading can obstruct weight management by causing anxiety and concern over what others think about us. Thinking this way can result in self-imposed pressure to prove something to a boss, sibling, spouse, or co-worker. As a result, we may eat to help relieve the stress caused by these feelings — or we may lose focus on weight-related goals.

Mind reading can directly impact health behavior if we make assumptions about what others think about our size, what we eat, or our competence using exercise equipment at the gym.

Learn how trying to be a mind reader can obstruct weight management by causing anxiety and concern over what others think about us in Stop Trying to Be a Mind Reader.

4. Catastrophic Predictions

The idea that you’ll never lose weight if you don’t do it now is a good example of a catastrophic prediction. This way of thinking creates enormous pressure to change. Although this pressure can yield results in the short run, it doesn’t work well as a long-term perspective. A now-or-never mindset builds resentment and is emotionally exhausting. You may believe that putting intense pressure on yourself to change NOW will eventually lead to healthy habits. But our minds don’t work that way.

5. Labeling

In most instances, labeling is a poor way of explaining our behavior. We are unintentionally reasoning our way out of a solution. In other situations, using labels can be a copout. When you label yourself stupid, lazy, disorganized, or lacking willpower, you’re saying you can’t change — and that lets you off the hook for managing your weight.

Read how Catastrophic Predictions and Labeling Won’t Help You Lose Weight.

6. Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning permeates many areas of our lives, including relationships, career, self-image, and certainly weight management. Having a strong emotional reaction each time you see the scale move in the wrong direction may cause a surge of negative emotions that leads to irrational thinking. Maybe you vow to eat nothing all day forgetting that each time you try this it ends in disaster. Or perhaps you feel strongly that you’ll never succeed and, as a result, you stop trying to eat right or stay active.

Read The Problem with Emotional Reasoning.

7. Demands

If you want to manage your weight long-term, “shoulding” yourself is not the best strategy. It may actually prevent us from doing what’s important. Even if you have short-term success guilting yourself into action, this won’t be effective in the long run. Even if it worked, who wants to feel guilty or pressured all the time? Telling yourself you have to do something strips away your perception of freedom and can lead to feeling disgruntled and even angry.

If we want to make lasting behavior changes and feel good about it, we need to stop talking to ourselves that way. Be nice to yourself. A simple change in words can make all the difference.

Read Why Making Demands on Yourself Won’t Help You Reach Your Goals.

8. Rationalization

Instead of blaming themselves for everything, some people blame others or their situation in life. Sometimes we come up with complicated explanations for our behavior so we don’t have to take responsibility for it. Yes, we do live in a culture that promotes weight gain and inactivity, but we still have choices. Some rationalizers are the defensive, angry types and others are intellectuals, debating like high paid defense attorneys. Some of us have spent years “spinning” the responsibility of our actions to make it someone else’s fault when we can’t reach our goals. Always shifting the blame bogs down our ability to achieve health goals.

Read Rationalization — It’s Not My Fault.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Why Making Demands on Yourself Won’t Help You Reach Your Goals

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

In the last few posts we’ve been reviewing thoughts that might interfere with achieving health goals. This week we will explore why making demands on yourself won’t help you reach your goals.

The psychologist Albert Ellis is famous for telling people to “stop shoulding on yourself.” I can’t think of an area in life where the word “should” is used more often than with diet, exercise, and weight management.

- I should get up early in the morning to work

- I should take my lunch to

- I guess I should join the gym

- I know I shouldn’t eat so much ice

- We should get back to shopping from a grocery

- I should just tell my husband not to buy me

Why do we use this word? In some situations, the word should may bring good results by reminding us of things that are right and most consistent with our beliefs. I should study for my test instead of going out with my friends. Once you say this you know you’ll feel guilty if you go out. Since you don’t like feeling guilty, you stay home even though you don’t want to. Doing well on the test reinforces your strategy to use the word should.

But sometimes, should is a way we superficially deal with a situation to make us feel a little bit better. If I am talking to my dentist and say, “I know I should floss more often,” this statement probably won’t lead to action. It’s used to relieve the embarrassment I feel for all the problems with my teeth. This type of should makes me feel like I’m doing something, even when I’m not and have no intention to. In a situation like this, using should takes the pressure off, but may actually make it less likely that I’ll change my behavior.

If you want to manage your weight long-term, shoulding yourself is not the best strategy. As in the dentist example above, it may actually prevent us from doing what’s important. Even if you have short-term success guilting yourself into action, this won’t be effective in the long run. Even if it worked, who wants to feel guilty or pressured all the time? Telling yourself you have to do something strips away your perception of freedom and can lead to feeling disgruntled and even angry.

Imagine if the Christmas-time bell ringer for the Salvation Army stopped you at the grocery store, shook his fist at you, and said, “I know you have enough money to contribute to help us. You should stop thinking so much about yourself and your family and give to those who barely have enough to eat or don’t have a home to live in.”

How would you respond? I suspect you’d react in one of two ways: Either you’d walk on by (even if you were considering a donation before he started his diatribe), or you’d feel guilty enough to reluctantly throw some cash into the red container. No matter what you decided to do, you wouldn’t feel good about the bell ringer—and next time you’d probably use a different entrance to avoid the red kettle.

No one likes being strong-armed, so why do it to yourself? Telling yourself you should eat and exercise in a certain way will make those activities less desirable. You’re almost certain to (1) rebel against yourself, or (2) engage in exercise and dieting with a chip on your shoulder. Either way, you won’t be able to keep this going very long.

In a way, you’re telling yourself you aren’t smart enough, good enough, or disciplined enough to make choices based on what you truly want.

If I tell myself, “I should have an apple, not the cake,” I end up losing no matter which food I choose. If I eat the apple I feel deprived. If I eat the cake I feel guilty. If I eat both of them I feel even worse.

Maybe you substitute a different word for should:

I have to

I need to

I ought to

I’m supposed to

These phrases yield the same results. If we want to make lasting behavior changes and feel good about it, we need to stop talking to ourselves that way. Be nice to yourself. A simple change in words can make all the difference. Instead of using those demanding should words, try something like this:

I could have the apple or I could have the cake.

I could go to the gym or I could stay home.

I can take the elevator or walk up the stairs.

I could order dessert or wait until later.

You are giving yourself a choice — not a command. With this approach you can weigh the options, looking at the pros, cons, and consequence of each decision. Sometimes you might decide on the cake, but you needn’t feel guilty if you figured out how it could work within your larger goal of being healthy. If you decide on the apple you don’t need to feel deprived, because you decided it was the best decision.

As you go through the day, watch for the times you “should” yourself and try viewing these situations as a choice.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: The Problem with Filter Focus

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

A friend of mine used to say, “Filter-focus!” when she saw a good-looking guy who grabbed her attention. She would fan herself as she repeated the phrase filter-focus, filter-focus. Her objective was to filter out thoughts about him so she could focus on what she was doing.

At any given moment we’re bombarded by information from at least four of our five senses. As children we’re easily distracted and don’t always filter and focus well. For instance, kids may dart into traffic when they see something interesting. But as we learn and our brains mature, we become better at filtering out a tremendous amount of data by prioritizing. This mostly happens “behind the scenes” without our awareness. This filtering activity often affects our attitudes and behavior.

Depending on our personality and experiences, we can learn to filter out information — or we can prioritize it in ways that cause unnecessary and harmful stress.

Some people filter out accomplishments and focus only on their deficiencies, especially those related to weight. An example would be ignoring the two pounds you lost, while focusing on a package of cookies you ate this morning. This viewpoint leads down a road of frustration and hopelessness, paved with the perceived tragedy of many failures. Don’t get me wrong, we do need to understand and evaluate our mishaps, but only if we also enjoy our positive attributes and success.

Filter-focus fallacy can expand to include our overall moods and life perspective. Choosing to mainly focus on the positive aspects of life changes your outlook on every situation, the people you encounter, and yourself. If you’re accustomed to negativity, the idea of changing to a positive focus may seem “soft” and unrealistic. “The world is a hard place,” these people say. “Better get used to it.”

Yes, bad things happen all around us — but what about the good stuff? If you let your mind process life according to the nightly news, you won’t feel uplifted or positive toward your own life and the people around you. School shootings, murder, scandals, politicians verbally attacking each other, traffic congestion, and impending bad weather, slightly tempered with a sprinkle of a feel-good story or humor — that’s the news, every day. If we want to experience joy, we should avoid seeing our lives from a nightly-news perspective. Furthermore, if we want to stay committed to healthy living, we cannot filter out our achievements and focus only on failures.

When I review a food journal with someone who has filter-focus problems, the conversation often goes something like this:

“Thanks for letting me take a look at this. You did a nice job of consistently tracking your food. Tell me a little bit about what went well and what you’re still struggling with.”

“Well, I’m still snacking too much at night and I know I need to eat breakfast every day, but I don’t. This week has been terrible for exercise because I’ve been working more and I’m just so tired when I get home.”

“Ok, but you did eat breakfast four times this week, which is an improvement, and I notice you’re taking your lunch a bit more instead of going out to eat.”

“Yeah, but I’m still eating out too much. I want to get out of the office and when my co-workers suggest it, I go. I just don’t seem to have much willpower when it comes to lunch, especially on the days when I skip breakfast.”

“I understand you still want to make improvements, but over the past several weeks you’ve been moving in that direction. What do you think you did well that led to you losing weight?”

“Well I’m just kicking myself right now because I wanted to lose five pounds in two weeks and I only lost three. I need to dedicate myself much more to exercise and sticking closer to the plan.”

Despite promptings, this patient could not give herself credit for her accomplishments. If you’ve ever been involved with someone who filtered out your accomplishments and focused on your imperfections, you understand the consequences. No matter what you do it isn’t good enough, and if you succeed at something they remind you of previous failures with statements like these:

“I wish you’d done that a long time ago, I don’t know why it took you so long to figure it out.”

“I see you made the honor roll, but why did you get a ‘B’ in that class. Were you goofing off?”

“Your sales figures topped everyone else’s this month, but you should aim higher than that.”

“If you people really cared about this project you’d be working more overtime.”

Do comments like this motivate you to do your best? Do they spur you on? I doubt it. Instead you feel beaten down. The joy of accomplishment is easily squashed, and after a while you think, “Why bother? Nothing I do will be good enough.”

When we talk to ourselves in the same way, the same feelings emerge. The other harmful aspect of filter-focus is that constructive criticism is no longer effective. When you or someone else finds fault with everything you do, one criticism becomes just like all of the others. On the other hand, when you’re able to focus on what you’ve done well you’re more likely to appreciate a valid critique.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Avoid “All or Nothing” Thinking

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

For just a moment, think about the first Monday of January. This is the day when people return to work and school after the holidays. Those who vowed to get in shape this year set their alarms early to nudge their bodies onto the treadmill or to the nearest gym. For many, this is the first day of their “diet.” Radio, TV, and the Internet are flooded with advertisements for weight loss programs and products. Many people who went to bed as late-night snacking slugs hope to awaken in the morning as die-hard dedicated dieters and fitness fanatics.

This type of all-or-nothing behavior is great for the $60 billion per year weight-loss industry because, in addition to first time customers, companies depend on restarts. The restarts are the people who join another program, buy an additional piece of exercise equipment, join a different gym, purchase another book, or hire a personal trainer. Often these consumers are declaring their “all in” mentality. This is the year they will change — just like last year, and the year before that.

Motivation, drive, and excitement can be instrumental in helping us accomplish important goals such as losing weight. But when we look at things in a polarized way, we end up repeating cycles of weight loss and regain. Whether related to health or other aspects of our lives, this all-or-nothing thinking can be frustrating, inefficient, and even catastrophic. Can you imagine what life would be like if people took the all-or-nothing approach to driving? Some days, people would drive under the speed limit, stop at red lights, and yield to pedestrians, but on other days they’d ignore all traffic laws — sort of like downtown Boston.

In reality, most of our behavior is on a continuum, even if our thinking isn’t. For example, if you think someone is a terrible person, that thought can easily become a belief that will impact how you respond to him or her. Although you probably won’t behave in an all-or-nothing way (hugging versus physically harming), your all-or-nothing thoughts (great person versus terrible person) have a significant effect on interactions. You certainly won’t go out of your way to know this person better.

When we think, “I’m either on a diet or out of control,” our behavior is likely to drift in that direction as well. Here’s an example of three all-or-nothing thoughts that might impact your eating and physical activity.

- If I don’t stay under my calorie goal I have failed.

- If I can’t get my heart rate up for 30 minutes, then exercise does me no good.

- I have no self-control when it comes to sweets; once I get started I can’t stop.

Let’s look at these thoughts. What happens if we believe the first example? Does that mean if you’re one calorie over the goal you have totally failed? Do you get discouraged at this point and perhaps overeat even more?

If you believe exercise is only useful if it’s intense for 30 minutes, how often will you miss the opportunity for a 10-minute walk that will reduce stress? How often will you ignore the benefits of exercising during TV commercials?

Is it really true that once you get started on sweets you can’t stop? Does this happen in all situations, no matter what?

Sherry’s problem was salty, crunchy, fatty foods. She told me potato chips were the worst, or best, depending on how you look at it.

“If I have one, I eat until they’re all gone,” she told me. “That happens every time?” I asked.

She shrugged. “Pretty much.”

Coincidentally, our weight management center was conducting research on preferences for regular versus baked potato chips during this time, so we had a stockpile of both kinds in the office.

“Hang on a minute, I want to test your theory,” I told Sherry.

I went to the back and filled a Styrofoam bowl with the regular, full-fat chips. I placed the bowl of chips in front of Sherry and said, “I want to try something with you.”

With a here-comes-a-magic-trick expression on her face, she agreed.

“I want you to eat a chip,” I said.

Sherry smiled, selected the largest chip, and willingly crunched, chewed and swallowed. Then I waited. I looked at Sherry in anticipation of her next move. Finally, she got a little uncomfortable.

“What?”

“Aren’t you going to eat the rest of them?” I asked.

“No.”

“Why not?”

With an uncomfortable laugh, she said, “Because you’re here!”

“If I leave the room, will you eat the rest of them?”

“Nooo.”

“What about on your way home? Will you stop and buy more?” I asked.

“No, I don’t think so,” Sherry said smiling.

“So it really isn’t true that once you eat one chip you can’t stop?”

“Well, I usually eat chips at home in front of the TV. I take the whole bag to the couch and before I know it, they’re all gone.”

“So when you eat chips in that sort of environment it’s hard to control yourself?”

“Exactly.”

Sherry’s belief that she couldn’t stop eating chips once she started wasn’t true. In fact, she could practice a lot of restraint in certain settings. She had options with potato chips. She didn’t need to accept the idea that they controlled her. Instead, if she wanted to eat chips in moderation, she could set up her environment to increase the likelihood for success. Maybe she could buy a vending machine size bag, or pre-portion her chips into smaller containers. She could commit to only eating chips at the kitchen table where she could truly pay attention to the pleasure from one serving. Or, she could only eat chips when she came to her weight management appointments. Lastly, Sherry might decide that keeping chips in the house was just too much work and the chips weren’t worth it. Whatever she decided, the crucial element was believing she could control herself — and we proved that during our session with the chips.

Countless other all-or-nothing thoughts can impact eating, such as:

- I totally blew it by oversleeping, missing my workout, and then skipping breakfast. No use trying to get back on track today.

- My presentation was a total disaster.

- Yesterday was great, but today has been the worst.

- I either avoid carbs altogether or I’m eating chips and cookies.

- Nobody cares anything about me unless they’re getting something from me.

- My husband always ignores my needs; it’s all about him, never about me.

- It’s either organic vegetables or no vegetables at all.

Whether the thought is about the weight loss process itself or another area of your life, it can impact your health behavior. If you’re so distraught by your worst day ever at your job that you can’t stomach the idea of going home, preparing dinner, and cleaning up the mess, you may end up ordering a pizza. If you feel nobody cares about you and your life is without purpose, why bother taking care of yourself?

This all-or-nothing thinking is one of many thought patterns that can get in our way, and we’re going to look at options to combat it. But before we do that, in the next articles we’ll examine other categories of thinking that derail us.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: The Bad Smell of Stinkin’ Thinkin’

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

In this article, we’re exploring how the relationship of thoughts, feelings, and behavior affect our eating and exercise habits. Thinking takes center stage.

Before we get started let’s clarify a few concepts and terms. Each of us has thoughts we can’t entirely control. Sometimes we know certain thoughts are ridiculous and we can easily dismiss them and ask ourselves, “Where did that come from?” We won’t be scrutinizing those thoughts. Instead, I want to focus on thoughts that matter — the ones that influence behavior and shape our attitudes and beliefs.

Beliefs are simply thoughts we accept as true. If your mind was a garden, thoughts would be seeds that quickly developed into seedlings. Beliefs and attitudes are the mature plants. Therefore, thoughts are full of potential to help us and provide a sense of well-being. Too often, however, they derail us — and that’s where this chapter can help. Let’s look at three clients whose thinking directly affected their attempts at weight loss:

- John needed to make changes in his diet before being approved for bariatric surgery. As I explained the MyPlate principles of healthy eating, John snapped back at me, “I’m not doing that. Nobody eats that way!”

- A client named Karmen told me her personal trainer said she was obese because she’d ruined her metabolism. According to him, regular, intense workouts were the only way to solve her weight problem.

- Becky’s mother always told her she’d never find a good man if she was overweight. Now 32 years old, 75 pounds overweight, and still single — Becky felt unlovable.

Can you see how John, Karmen, and Becky handicapped their weight management efforts before they even started? John’s belief that only freaks would eat a balanced diet was like putting up a huge DETOUR sign on the road to weight loss. Karmen was overwhelmed by thinking her metabolism was forever ruined, and only a lifelong extreme exercise program would treat her condition. She was bound to give up. Becky’s mother primed her to feel lonely and hopeless in pursuit of a relationship. She quickly dismissed any man who showed interest in her, yet paid close attention if anyone seemed put off by her weight. Eating would become her friend, her solace.

These three examples above show how thinking can have a clear, direct relationship to weight. However, sometimes the beliefs that affect eating and physical activity are more subtle and indirect:

- At work, Steve’s philosophy was, “If I don’t do this, it won’t get done.” At the same time, he had high standards for work and wouldn’t delegate tasks to others. This led to 14-hour days with no time for exercise. Being strapped for time and chronically sleep deprived, he often ordered carry-out and drank caffeinated sugar- sweetened beverages all day long.

- For years Sarah tried not to even think about her family, but she couldn’t get them out of her mind. Her alcoholic father’s relapse made her both angry and sad. Her sister’s lifestyle choices led to financial problems, and Sarah felt obligated to help. Sarah seemed to always feel upset, and to keep those emotions under control she distracted herself in some way — often by eating something she knew she shouldn’t.

- Lisa often thought about how terrible it would be if she disappointed her boss, her husband, or her kids. She believed she needed to be everything for everyone, and this led to anxiety she couldn’t control. She felt anxious much of the time and eating became her Xanax.

The First Steps Toward Change

The first step toward thinking differently is to recognize beliefs and feelings behind the behavior we want to change. Examining situations and their outcome helps pinpoint our problematic behavior. For example, let’s consider Lisa from the last paragraph and imagine how she might respond to the following scenario:

Lisa’s boss asks for a volunteer to lead a fundraising project (situation). Lisa thinks, “My boss will be disappointed in me if I don’t do it,” (thought) and despite her already overcommitted schedule, she feels pressure (emotion/feeling) to take on the task. For Lisa, this becomes a question of which option is most unpleasant: the anxiety of not volunteering versus the anxiety and stress of accepting extra work she doesn’t want. Either way, she feels stressed because her thinking has created a lose-lose situation.

Lisa could think differently: “I’m not sure what my boss expects, but even if he does want me to do this (and I have no evidence that he does), it’s unreasonable for me to be everything for everybody. Other people in the office can benefit from taking a turn. The people who truly care about me will still feel that way even if I don’t always do exactly what they want.” She could also talk to her boss in private about his expectations. Thinking differently helps Lisa feel less anxious about her situation. Her new thinking may feel awkward at first but allows her to make the brave choice of saying “no” to more responsibility.

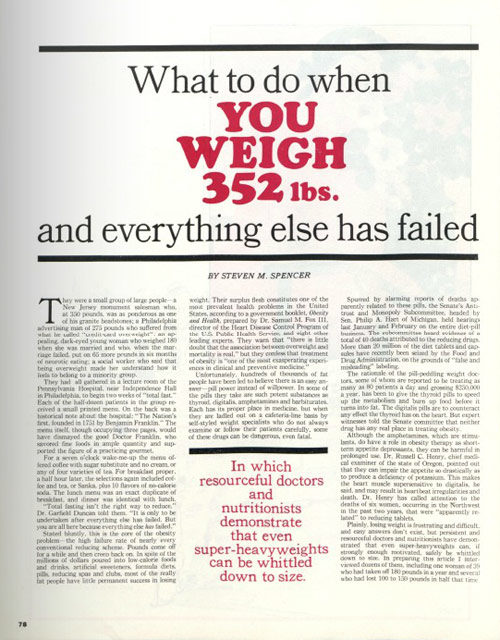

What to Do When You Weigh 352 Pounds and Everything Else Has Failed

Stated bluntly, this is the core of the obesity problem—the high failure rate of nearly every conventional reducing scheme. Pounds come off for a while and then creep back on. In spite of the millions of dollars poured into low-calorie foods and drinks, artificial sweeteners, formula diets, pills, reducing spas and clubs, most of the really fat people have little permanent success in losing weight.

Those words were written 50 years ago this week in a Saturday Evening Post article by Steven M. Spencer that looked at last-ditch efforts by obese people to lose weight, but it could have just as easily been written today. Despite half a century of studies, novel diets, advances in surgery, and potentially lucrative drug options, more people are obese today than in 1968. Back then, the estimate was one in five adults were obese. Today it’s one in three.

Some things have changed. In the late ’60s, people were just realizing that using digitalis, amphetamines and thyroid pills to lose weight had terrible consequences. The Senate had just concluded hearings on the largely unregulated diet pill business, and restrictions were imminent.

Some of the up-and-coming methods weren’t much better. One doctor promoted a two-week starvation diet that consisted mostly of Sanka and diet soda.

Others, while not necessarily extreme, have since fallen out of favor. Dr. Kempner’s famed rice diet was “low-fat, low-protein and almost unbearably salt-free” — the opposite of the high-protein, low-carb paleo diets currently in vogue.

Another new option for rapid weight loss in 1968 was surgery. The operation, which involved bypassing most of the small intestine, had only been performed in a few, extreme cases. Doctors eventually realized that this particular surgery had many unpleasant consequences, including diarrhea, night blindness, osteoporosis, malnutrition, and kidney stones. More effective surgeries soon took its place.

Despite the apparent simplicity of the weight loss solution (calories in must be lower than calories out), doctors and researchers of the 1960s were realizing that humans are mysteriously, frustratingly complex. Spencer wrote, “Why does the obese person find it so hard to reduce? The reasons, of course, must be sought in the baffling perversities of human motivation, in the tangle of social, psychological, genetic and biochemical strands that drew him into the fat life in the first place.”

Fifty years later, many still try to untangle their motivations in the same places: gyms, structured meal plans, and doctors’ offices. Of course many aspects have moved online, from support groups to exercise videos to illegal diet pills. And some people now reject society’s obsession with the slender altogether and embrace fat acceptance.

But the fact remains that most people want to weigh less than they do now. A socialite once quipped, “You can never be too rich or too thin.” The person who invents the key to successful long-term weight loss will likely be both.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Are You an Emotional Eater?

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

People commonly use food to deal with stress. After all, food is an enjoyable distraction and easy to find. When you feel stressed at work, a vending-machine candy bar may only be steps from your office. At home, our well-stocked pantries and refrigerators make emotional eating an easy way to cope. And once in the kitchen, what foods call to us? It certainly isn’t lettuce or carrots. Most likely we hear a siren song from ice cream, chips and salsa, cake, or some other high-calorie food.

One TV commercial shows a sniffling, downtrodden young woman paying for items at a convenience store. She places ice cream, potato chips, and a box of tissues on the counter. The elderly cashier empathetically says, “Oh, honey, he broke up with you again?” Viewers understand this because emotional eating is so common. This young woman is using food to deal with sadness, abandonment, and anger.

In my weight management groups and individual sessions with people trying to lose weight, I frequently ask, “What influences you to eat when you aren’t hungry?”

Many people respond by saying, “I’m an emotional eater.” Even among those who deny emotional eating, we often discover patterns of weight gain during stressful times and life transitions that suggest otherwise. And it’s not just negative stress – positive stress also can influence eating and physical activity. Exciting life transitions, sometimes referred to as eustress, can impact our behavior. These stressors may include the birth of a child, a job promotion, a new house, or a new relationship. We might gain weight because we party and stop exercising at college, take on the unhealthy habits of a spouse during our first year of marriage, use food as entertainment when we travel, or celebrate anything and everything with cake. Over time, eating during periods of eustress or distress becomes a pattern that seems normal. We eat without much awareness of the circumstances and emotions that contribute to our food choices.

Redefining pleasure can help us eat healthy during times of celebration and still enjoy life. Monitoring weight, physical activity, and diet can keep us from veering off track during exciting times. But for many people, persistent distress is more connected to unhealthy weight than positive stress. With or without awareness, stressed-out employees, moms and dads, college students, and even children self-medicate with food.

I don’t want to turn you into an unemotional robot when it comes to eating. I do want to help you become intentional about how you react to stress. Being deliberate and aware of our reactions is often a challenge, because the interaction between emotions and eating is complex. Fortunately, we can begin making positive changes without understanding every detail of why we eat.

To simplify, let’s accept that emotions affect everyone’s eating habits to a certain degree. Your unique patterns may be so ingrained that you barely notice them. To better understand your patterns, it may help to answer the following questions:

- How often do you emotionally eat?

- When do you tend to do this (evenings, weekends, or when your mother-in-law visits)?

- How much food (and what) do you usually eat?

- At the time, do you realize you’re eating because of your emotional state or is it more like a mindless grazing pattern?

- Do you lose your appetite when you’re stressed but then end up overeating when you finally relax?

- Do you intentionally plan emotional eating (making sure you’ll be alone or have your preferred foods)?

- Do you eat until you’re uncomfortably full and/or feel out of control?

As the questions above illustrate, people have different patterns of emotional eating. You may be a grazer — tasting food as you hurriedly prepare dinner or inching your way through a sleeve of crackers while helping a reluctant child complete his homework. Maybe you tend to not eat when you’re stressed, but overcompensate later when the pressures of life subside. Or you may be a frequent binge eater, consuming food until you’re uncomfortably full, feeling out of control and only eating in private, and feeling embarrassed and guilty when you finish. If the last sentence describes you, consider seeking professional help. A therapist skilled in eating disorders can help you better understand your behavior.

In the next article, we’ll cover how to cope with emotions in a healthy manner.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Low Carb Eating

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of Dr. Creel’s columns here.

This week’s column is based on a questions from readers. Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

This week I’ve decided to address two questions related to low carbohydrate eating.

- High-protein “keto” diets seem to be extremely effective for many people. What’s your opinion of them as a weight-loss expert?

- I just love starchy food – bread, rice, potatoes – and I am not interested in going “paleo” and cutting them out of my diet entirely. What are some healthy weight loss tips?

Thanks for your questions!

Generally speaking, I’m not a fan of truly ketogenic diets for weight loss. Restricting carbohydrates to 20 grams per day — about what you’ll find in an apple — is not a long-term solution for most people with excess weight. These diets lack balance, eliminate important nutrients, and are generally not sustainable. But, in my experience, most people who say they are following a ketogenic diet are actually following a reduced carbohydrate diet that is not putting them into ketosis. These lower carbohydrate diets are more realistic and can be an effective approach to weight loss. In fact, several large studies show that low carbohydrate diets and low fat diets show similar long-term weight loss.

What matters most is finding a way to consume fewer calories through nutritious, filling foods. If you tend to do better on a lower carbohydrate diet, make sure your protein choices are healthy ones like fish, chicken, turkey, and eggs. At the same time, choose healthy fats that come from avocados, nuts, and vegetable oils. If your low carb eating consists of bacon, sausage, buttered coffee, pork rinds, and ribeye steaks, you may want to rethink what you’re doing.

Personally, I love healthy carbohydrates. Foods like oats, quinoa, brown rice, and fruits provide energy, fiber, and a multitude of nutrients. It is important to limit our processed grains and foods with added sugars (biscuits, sweet cereals, sugar-sweetened drinks, etc.). For my bread, rice, and potato-loving questioner, try balancing your meals with a lean source of protein and vegetables.

- Instead of a large plate of pasta with garlic bread, experiment with making a pasta dish that has diced vegetables and chicken along with a side salad. You’ll still get your pasta, but you won’t overdo it.

- Use rice to accompany a vegetable/meat stir-fry. You’ll enjoy the rice, but it won’t be the star of the show.

- Try hearty whole grain bread on a sandwich loaded with vegetables, avocado and a lean protein.

- And potatoes — they are packed with potassium, vitamin C, and fiber. If you love them, eat them. Just remember that preparation matters. Load a baked potato with ingredients like diced tomatoes, chives, spicy black beans, roasted chickpeas, mushrooms, or lightly sautéed spinach.

Lastly, don’t forget that food is fuel. The timing of our meals and snacks as well as what we’re eating should provide us with energy to move our bodies. In short, our diet fuels physical activity, a key to long term weight loss.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Gaining Weight After Quitting Smoking

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

This week’s column is based on a question from a reader. Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Reader Question: Help!!! I am one of those older women who finally quit smoking and find myself twelve pounds heavier. I eat the same way I have always eaten, although not necessarily the healthiest. All the weight is in the midriff/waistline area. I am so uncomfortable I can barely bend down. I hate the word diet, but I need to do something that I can hopefully stick to. Can you help?

First of all, congratulations on your persistence with quitting smoking—what an accomplishment!

Although smoking cessation often leads to weight gain, the net effect is generally a great improvement in overall wellbeing. One large study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed gaining weight after smoking cessation did not offset the beneficial effects on heart health.

But to your point, weight gain is something few desire, and gaining fat around our organs is related to increased risk of diseases. The obvious, ideal situation is to remain tobacco-free while maintaining a healthy weight.

Although there might be a slight change in metabolic rate after quitting smoking, it appears that increased appetite is more to blame. Although it might not seem like your eating has changed since you stopped smoking, sometimes these changes are so subtle we don’t recognize it. Consuming only 100 calories more than we burn each day can lead to 10 pounds of weight gain in one year. So, to your question—what’s a person to do?

There is no perfect diet for weight loss. In order to lose weight, we must create a calorie deficit. Many different diets/plans can help you accomplish this. Unfortunately, successful weight loss is often short-lived because the plan is unrealistic or people struggle to commit to a new lifestyle. Although I don’t know anything about your medical conditions, limitations, or preferences, I usually encourage the following:

- Begin monitoring what you are doing—track your food intake and your physical activity.

- Identify problem areas such as mindless snacking, skipping meals and overeating later on, late-night eating, portion problems, dining out, eating too few vegetables, or low levels of physical activity.

- Focus on a few small changes related to improved eating and increased physical Perhaps you could start by walking an extra mile per day and decreasing your calories by 300-500 per day.

- Consider professional accountability with a registered dietitian, fitness professional, physician or mental health provider specializing in weight management.

- Monitor trends on your scale to help you figure out what is working.

- Lastly, be patient. Frustration and perfectionism can kill commitments before they ever begin.

Thank you for your question. We’d love to hear back from you in the future. Good Luck!

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Creating Weight Loss Habits and a New Identity

We are pleased to bring you this regular column on weight loss by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Researchers Rena Wing and James Hill asked, “What do people who succeed at losing weight and keeping it off have in common?” To answer this question, they invited people who’d lost at least 30 pounds and kept if off for a year or more to join the National Weight Control Registry. Over the last 20 years, along with their colleagues and students, they’ve published studies to help us learn from those who succeed. One of those studies is related to a mindset that may help us succeed with long-term weight management.

In that study, Dr. Mary L. Klem provided questionnaires to over 900 people in the registry and assessed how they viewed the effort, attention, and pleasure associated with maintaining a lower weight. On average, the participants kept off about a 60-pound weight loss for almost seven years. They reported it became easier to keep their weight steady as time passed, requiring less effort and attention. And, they said the pleasure of maintaining weight loss did not diminish. Less work and continued satisfaction—who wouldn’t like that result?

This study shows how commitment can lead to habits that make it easier for us to maintain new behavior. These new, healthier behaviors usually require less motivation and attention because, well, they’re habits!

Why Should You Develop New Habits?

When you develop habits with intention (that is, on purpose), and merge these behaviors with the most important aspects of your life, they become part of your identity. Imagine you begin riding a bike to work or walking an extra mile every day. Imagine taking the stairs instead of the elevator, which is too crowded anyway. Visualize having a fresh, colorful salad for lunch on most days. Imagine having an occasional half-cup scoop of your favorite sherbet for dessert instead of a nightly bowl of ice cream with hot fudge sauce. Imagine having your favorite decadent food as a special treat, but not eating it in excess.

Once you and others begin to see these behaviors as part of who you are and what you do, these habits become part of your identity. Just as you might describe yourself as a non-smoker or pet lover, you also describe yourself as a healthy eater or a regular exerciser. Once this happens you begin to forget old unhealthy behavior patterns and the “new you” eventually becomes the “old you.” The new way of viewing yourself becomes part of who you are.

I can’t promise this is always easy. Many overweight people find it hard to see themselves as an exerciser or healthy eater because they don’t look fit. Buying extra-large clothing or looking at yourself in a full-length mirror can trigger negative thinking. Women compare themselves to size 4 fashion models, while guys sometimes look at their favorite athletes and tell themselves, “I’ll never get there. No use trying.” This attitude stands in the way of creating a new identity, and it definitely influences behavior. In fact, it becomes a vicious, self-fulfilling prophecy.

How Do We Define Our Identity? A Story

One of my clients told me about an encounter that shows how appearance, background, and conditions need not define our health identity.

Rob has been overweight for years. He’s a guy who loves football, beer, and a casual lifestyle. He’s single and works with a group of other men who don’t cook or even consider what they eat. As a result, Rob consumes a lot of fast food. In his mind, that’s what guys do, and so it became part of his identity. Other parts of his identity, less obvious to his friends, are his diabetes, which requires more insulin with each pound he gains, and his recent diagnosis of high blood pressure. Rob also has a heart for helping others, whether it’s taking care of a sick family member, building housing in Haiti, or helping a friend move. In a recent visit to my office he told me about an incident that made an impact on his weight loss efforts.

Doc, you won’t believe what happened to me this week. There’s this homeless guy I see almost every day close to my work. He’s maybe 50 or so—heck we’re probably about the same age. Anyway, he has dirty long dreads and he pushes around a shopping cart with some of his personal items. As far as I know he never really panhandles, but for some reason I just feel bad for him. So the other day I saw him on my way to lunch and decided to pick up something for him to eat, too. I was at Hardee’s and after I finished eating, I ordered him a cheeseburger, fries and a Coke. I thought I was doing something nice for the guy, you know? So I drove over to where he hangs out and I rolled down my window and said ‘Hey man, come here, I got you some lunch.’

He walked over to my car and I handed the sack through the window. But instead of taking the food and saying thanks, he just looked at the sack and said, ‘What’d you buy me?’

I said, ‘It’s just a burger and fries. Go ahead, take it.’

Then this guy says, ‘Man, I don’t eat that kind of stuff.’

I was like, ‘You mean, you don’t want it?’

Then he said, ‘Nah man, I got diabetes and my doctor told me that sort of food will kill me. If you want to get me something to eat, go over to McDonald’s and get me a salad.’

So here I was sitting in my car, with a homeless guy refusing the food I bought him because it wasn’t healthy enough. I couldn’t believe it!

Rob went on to tell me this incident made him think about his own behavior. If a homeless person can make good food choices, surely he could too. It also demonstrated that physical appearance and our surroundings don’t need to dictate identity. Rob assumed this man’s dirty clothes and unkempt appearance meant he wasn’t worried about what he ate.

Similarly, overweight people often find it difficult to view themselves as healthy because of their weight or appearance. Remember, a healthy weight results from healthy behaviors. In most cases it won’t lead you to a size four or ripped abs. Healthy people come in different shapes and sizes and I encourage you to let go of “ideal weights.” Although weight is related to health, it doesn’t define it.

Your Identity Is More Than Your Weight

It’s also crucial to accept that our size is only one component of appearance, and appearance is only one small part of who we are. Our intellect, personality, interests, abilities, purpose and pursuits need not be overshadowed by weight. Instead, if our drive for a healthier weight is integrated into other meaningful aspects of our lives, our weight management efforts won’t feel like a project disconnected from who we are. If I view managing my weight as part of becoming a better parent because I can go bike riding with my child, then managing weight takes on new meaning. If faith is a driving force in your life that encourages you to help others, your weight and health choices can either help or hinder your efforts.

Finding time to exercise doesn’t need to take away from what we give to our careers and the people we love. On the contrary, it will help us think more clearly, work more efficiently, manage stress better and probably increase our productivity.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel. Other recent columns:

- The Difference Between Motivation and Desperation

- How Important Is Exercise for Weight Loss?

- Tips for Eating Smart, Part 2

Featured image credit: Shutterstock

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: The Difference Between Motivation and Desperation

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

When you’ve failed at weight loss many times, your desire to change can turn into something that seems like motivation but isn’t. Loretta’s story is a good example.

Loretta showed up 15 minutes late for her psychological evaluation for bariatric surgery. I knew little about her aside from the information in her medical records. In her chart, I found that Loretta weighed well over 400 pounds and had diabetes, sleep apnea, arthritis, and low back pain. She checked the African American box on her intake form, and I noticed her address was in the middle of a crime-ridden part of a nearby city. When I met her in the waiting room she rocked backward and then forward while pushing on the arms of the chair in order to get to her feet. She groaned and grimaced with pain while walking with me to my office, barely acknowledging my introduction. She didn’t apologize for being late and seemed uninterested in small talk about weather or traffic. After we sat down, I explained the purpose of the required evaluation was to make sure surgery was a good fit for her, and if so, determine what things she could do to best prepare for the operation.

As Loretta began telling me about herself, it was clear our lives were only similar in the sense that we were both raised without much direct influence from other cultures and races. Her urban speech patterns were unlike mine, and her life was riddled by poverty and family members incarcerated or addicted to drugs. She casually admitted to having a drug problem in the not-so-distant past. On the other hand, I grew up in a Mayberry-like small town insulated from most of the problems found in inner cities.

Although I’ve tried to educate myself about other cultures and interact with people different from me, I can’t change the color of my skin or how I grew up. I could not simply, without invitation, step into Loretta’s world and understand her life. Our differences were important to her and she didn’t want to talk about the thing that was most personal to her—her weight—with someone like me. How could I blame her? After all, it’s hard enough to talk about personal struggles with someone who understands where you come from. Revealing these things to a stranger from a different culture and race adds to the difficulty.

I listened intently to Loretta and paid close attention to her body language. Although I tried hard to connect, she spoke to me with distrust, answering my questions with curt frustration. She was holding her cards close to her chest, afraid if I got a glimpse I’d take advantage of her. She feared I would win the game and taunt her with condescending psychobabble. Like many patients in this situation, she probably believed I’d use her words against her when it came to deciding if she was an appropriate candidate for surgery.

My attempts to convince her we were “on the same team” and I wanted to help did not resonate. I had real concerns that her lack of a support system, combined with financial hardships, would cause problems for her after surgery. Would she be able to afford the vitamins she needed to take daily for the rest of her life? When she couldn’t use food to cope with life difficulties would she turn to drugs again? Although she couldn’t see it, surgery could make her life worse if she wasn’t ready and equipped to make the necessary changes. As I continued to probe about how she would manage various aspects of her life after surgery, she stopped me.

“I don’t like where this is going.”

I put down my pen and stopped taking notes. “What are you concerned about?”

“I want to change my life.”

“How do you want your life to be different?” I asked, as our eyes finally connected.

Her expression softened and her eyes welled with tears. Like the small movement from the torque on a lid of a never-opened jar, I could sense something was about to give way. At that moment I didn’t notice her body that 30 minutes earlier had fallen into the oversized chair, out of breath from walking to my office. I didn’t notice her skin tone or the fullness of her face. Our age difference and dissimilar upbringings were insignificant. I just looked into her eyes and felt the gap between us closing. In a strained, high-pitch voice required to delay an ensuing sob, she quickly exclaimed,

“I can’t even wipe my own ass anymore.”

I didn’t know what to say. There it was, one of the most personal and embarrassing aspects of her life, out in the open. In those few words, she ripped through the veil I’d been tugging at the entire session. But I wasn’t ready for it; I could no longer sustain eye contact. It was like I accidentally saw her naked and was sorry I embarrassed her. As I felt the weight of her troubles, compassion stole my words. I looked down, nodding my head.

“I can only imagine how that makes you feel,” I said, after a long pause.

Her size had robbed her of her dignity. She was angry. As we continued talking, I learned she had been this size for quite some time. She depended on her husband to prepare food and help her dress, bathe, and get into and out of her car. It seemed illogical that up to the point of seeking bariatric surgery, she had done little to change course. How could it be that Loretta, like many other people, hated her situation so much, wanted to change, yet seemingly did nothing about it for so long?

Clearly, Loretta wanted to lose weight. In fact, she told me she’d wanted to lose weight for a very long time. Despite her desire for a different life, I imagine she had misguided family members who said, “When she wants it bad enough, she’ll do it.”

But Loretta’s problem wasn’t lack of desire. She had a strong desire to lose weight, but she wasn’t motivated: Loretta was desperate. A simple comparison will help explain what I mean.

Imagine you’re stranded on an island by yourself. You have sources for food, water, and primitive shelter. You’re happy to be alive, but also desperate to leave the island, interact with other humans, and enjoy a hot shower. Month after grueling month you try everything to escape the island—sort of like the old TV show Gilligan’s Island. After years of failed attempts, you still want to leave, but you’ve given up hope. Deep down you believe nothing will work—and you’re losing motivation. Any new idea to get off the island leads to a half-hearted pursuit before giving up. You’re so demoralized that you can no longer tell the difference between good ideas and dead ends—they all seem alike.

This is the point Loretta reached with weight management. Someone told her about bariatric surgery and she felt so desperate she made an appointment. She wanted to lose weight, had many good reasons to change, but wasn’t motivated. Our conversation revealed that, to her, bariatric surgery was no different than the grapefruit diet, the cold shower and potato diet, or having her mouth wired shut. In her desperation she hadn’t considered how this procedure was different than everything else she had tried.

Because of her perspective, she wasn’t ready to do the work required to be successful with bariatric surgery. When we offered to help Loretta prepare for surgery by changing her diet and beginning a modest physical activity program, she seemingly lost interest. Maybe over time she became motivated and pursued help elsewhere. Perhaps she’s still on her island—I hope not.

Desperation occurs at the intersection of hopelessness and motivation. We want to change, but have lost hope. We consider drastic efforts without truly believing they’ll lead to success, and after a while the drive to change begins to fade away.

Desperation can lead to motivation, but not always. Desperation can also rob us of clear thinking and make us vulnerable to things that will harm us, while safer solutions rest quietly within our reach. Many times people repeat the old saying: “You have to hit rock bottom before you can change.” In other words, life has to get really bad before we’re desperate enough to make changes. This can be true for weight loss, and sometimes it works, but it only works if someone will help you out of the mire and offer a safe, realistic plan. Even then, you must accept the help, believe in the plan, and do your part to make it happen. Otherwise, desperation usually leads to taking whatever someone will give you and hoping things will miraculously work out.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: How Important Is Exercise for Weight Loss?

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Here’s a story I’ve heard many times.

I hired a trainer I saw once a week for two months. I endured grueling workouts and was pretty faithful about working out on my own several times per week. I felt great, my endurance improved, and I could hold a plank for two minutes. But I only lost two pounds. Six-hundred dollars for two pounds! It doesn’t seem fair, nor does it make sense.

I agree this doesn’t seem fair. After all, when we work hard we want results. However, if we think about it logically, the results do make sense. Compared to making dietary changes, the short-term weight loss we experience from moderate exercise is modest at best.

Shantell is a good example. She reluctantly told me she drank approximately 12 regular sodas per day. Not counting french fries, she hadn’t consumed a vegetable in weeks. She and her kids ate fast food almost every day, and the meals she prepared at home included bologna sandwiches, hot dogs, or fish sticks. She would round out her meals with macaroni and cheese, potato chips, or tortilla chips. Although she didn’t eat a large volume of food, her diet needed a major overhaul.

Instead of trying to change everything at once, we focused on simply decreasing her soda consumption.

To my amazement, after our meeting she totally stopped drinking the ten-teaspoons-of-sugar-per-can stuff. When she returned a month later, she had lost 16 pounds. She didn’t make other changes in her eating, just the soda. If we assume Shantell consumed the same number of calories she was burning at the time we first met (her weight was stable), any calorie reduction would lead to weight loss. Table 2 illustrates how decreasing her consumption of soda (a total of 1800 calories per day) could lead to almost 16 pounds of weight loss in a month. Remember, burning 3500 calories more than we absorb equates to one pound of weight loss. So the math makes sense. Although Shantell’s diet still needed a lot of work, she was able to lose significant weight with only one change in her diet.

Now let’s look at how much exercise Shantell would need to do in order to lose a similar amount of weight. She weighed about 350 pounds, so walking burned more calories for her than for someone who weighed less and walked at the same speed. Think of it this way: The more someone weighs, the more work they do when moving that weight a given distance. For example, walking a mile with a 40-pound backpack requires more calories than walking a mile without it. In addition, because of her excess weight, Shantell’s resting metabolism was higher than an average-weight woman. I estimated she burned about two calories per minute simply sitting still. Table 3 shows Shantell would burn approximately 140 net calories per mile and would need to walk about 13 miles per day to burn the same number of calories she saved by not drinking 12 cans of soda. At two miles per hour, that would be almost 6½ hours of walking each day!

If you don’t drink 12 sodas per day, this example may seem a little extreme. But even if your extra 500 calories come from late night grazing, you’ll find it hard to “undo” those dietary indiscretions with physical activity. The point of these math gymnastics is to demonstrate that burning calories through exercise is generally more difficult than saving calories by eating differently.

This is especially true for people who can only exercise at low intensity. An elite runner can burn a lot of calories during an hour of exercise, whereas someone taking a slow walk burns far fewer calories. The runner may cover ten miles during that hour, while the overweight person walks two miles an hour. Many studies back up this principle of diet-versus-exercise for weight loss. We know that, in the short run, exercise doesn’t directly cause much weight loss. When we look at the long run, it’s an entirely different story.

| Diet Induced Weight Loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet Change | Calorie Savings per Day | Calorie Savings per Month | 30-Day Weight Loss |

| Stopped drinking 12 sodas/day | 12 sodas x 150 calories each = 1800 calories | 1800 calories x 30 days = 54,000 | 54,000 cals/3500 = 15.5 pounds |

| Walking Time Required to Lose 15.5 pounds in One Month | ||

|---|---|---|

| Extra Calories Burned/Mile | Miles of Walking to = 1800 Calories | Time required to walk 12.8 miles at 2 mph |

| 200 calories per mile – 60 calories burned at rest = 140 net calories | 1800 calories/140 calories per mile = 12.8 miles | 12.8 miles @ 2mph = 6.4 hours |

In order to understand long-term weight loss success, researchers study people who are good at it. Many studies show that people who lose weight and keep it off are

physically active. Data from the National Weight Control Registry and many studies conducted by Dr. John Jakicic at the University of Pittsburgh tell us that exercise is a crucial component in keeping lost weight from reappearing. Although studies vary on exactly how much exercise is necessary to keep weight off, most experts agree that engaging in 250 to 300 minutes of exercise each week will greatly increase your chances for success.

You may wonder why short-term weight loss from exercise tends to be modest, yet exercise is almost a requirement if you want to prevent weight regain. Researchers have not yet conclusively demonstrated why exercise is related to long-term success in weight loss. Although exercise, especially resistance training, may help prevent muscle loss and a lowering of metabolic rate that accompanies weight loss, not all studies support this idea. But when we look at the many other benefits of physical activity, we can draw logical conclusions about the long-term benefits of exercise.

- The longer we stick with an exercise routine, the more fit we become. As we become more fit we’re able to increase our exercise intensity for longer periods of time. The more we can do, the more calories we burn. When we’re feeling fit we gravitate toward physically challenging things that burn more calories.

- Exercise improves mood. If we feel less depressed and anxious we’re less likely to eat emotionally or be distracted from personal health goals.

- While exercising, we are not sitting in front of the TV. If we aren’t sitting in front of the TV, we can’t be eating in front of the TV.

- If we invest in our bodies by taking time to do good things for them, we probably don’t want to abuse the body with unhealthy eating. That would be like intentionally driving through the mud after a car wash.

- For those who enjoy physical competitions with themselves or others, eating is fuel for those endeavors. If high octane (healthy food) is available, we use it.

- Feeling accomplished about physical activity can improve confidence in other areas, including wise choices in what and how much we eat.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Tips for Eating Smart, Part 2

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Last week I offered four eating tips to help you lose weight and keep it off in a healthy manner. Here are three more helpful hints to help you manage calories and develop sound eating habits.

5. Choose Whole Grains

Our bodies like to operate on sugar (glucose), especially when we exercise at high intensities. When we eat whole grains, complex carbohydrates break down and sugar slowly enters our bloodstream, ready for use by our brain and working muscles. Whole grain foods such as wheat bread, brown rice, quinoa, and oats are rich in vitamins and minerals as well as fiber. Whole grains can be slightly higher in calories, which you will see if you compare white bread to whole wheat bread, because they contain the germ of the seed — a source of healthy fat. Despite the slightly higher calories, you’ll probably feel fuller longer because the whole grain fiber slows the rate at which food empties from the stomach. In addition, many foods made with refined grains (crackers, muffins, pastries, cookies, etc.) have added fats and sugars that boost the calorie count and increase our drive to overeat them.

6. Eat Lean Protein at Meals and Snacks

Calorie-for-calorie, protein tends to be more satiating than fat or carbohydrates. If I asked you to rate your fullness after eating 300 calories of pasta with red sauce (carbohydrates) versus the same calories worth of cheesecake (a tiny piece loaded with fat), compared to boneless skinless chicken breast (almost entirely protein), which would fill you up the most? Studies show it would be the chicken breast. Protein is important to help us feel satisfied after eating. Thus, adding an egg to your breakfast or a low-fat cheese stick to your afternoon snack may help curb overeating later in the day.

7. Watch for Hidden Fat

For several summers during college I worked breakfast and lunch room service in a high-end hotel. Each morning, dressed in my white Oxford shirt, black pants, and bow tie, I would grab something quick to eat between orders. Oatmeal was my favorite. I wasn’t sure why, but this was the best oatmeal ever. I thought maybe the hotel ordered exotic oats from overseas, which would explain the silky texture and rich flavor. Each morning I scarfed down a bowl or two of what I thought was the healthiest thing I could get my hands on. One morning I happened to enter the kitchen when Ms. B, as we called her, was making a large batch of the good stuff. Ms. B was a sweet black lady from Alabama who called everyone Honey. She seemed to cook from the depths of her soul and her food tasted better because you know she prepared it just for you. I can only imagine she learned to cook from her mother, who learned to cook from her mother.

Having family from the South, I knew all about the fat-is-flavor style of cooking. But I couldn’t believe my eyes when I walked in on Ms. B mid-oatmeal and saw her pouring a large carton of half-and-half creamer into the oats. I never imagined someone could do that to oatmeal! That day I learned a valuable lesson about hidden fat, especially when dining out. People often underestimate the calories in food because they don’t account for added fat, especially when others prepare it. Remember, one gram of fat has nine calories. A teaspoon of butter contains about four grams of fat or 36 calories. A stick of butter has over 800 calories (think cookies), compared to an equally sized banana of around 90 calories.

Follow This Diet

In summary, there is no best diet for weight loss and weight loss maintenance. But consuming a diet that’s rich in vegetables, lean protein sources, fruits, whole grains, and low-fat dairy will make weight loss more likely and give you the best chance of preventing diet-related diseases. In addition, eating a balanced diet can make you feel more energetic and give you the fuel to exercise consistently.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Getting Started with Weight Loss

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by David Creel, PhD, RD, who is a weight management specialist and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

Most people who want to lose weight try diet after diet, feeling worse after each successive failure. The weight almost always creeps back, along with discouragement and anger at themselves. Their hope quickly fades.

Statistics show that the probability of achieving and maintaining a ten percent weight loss without bariatric surgery is one-in-six. But I promise you that losing weight and keeping it off isn’t based on luck.

I don’t believe people are doomed to obesity. Although losing weight is never easy, I believe each of us has the ability to make permanent changes that result in a healthier weight. In these columns, which are based on my book, I plan to share the nutrition, exercise, and psychological principles I believe matter most.

Healthy living doesn’t look exactly the same for each person. Instead of a rigid, restrictive diet plan, we’ll explore how thoughts, emotions, and past experiences can work in your favor. Stories and patient experiences will help you change your thinking and strengthen specific skills, including:

- maintaining persistence

- eating mindfully

- setting goals

- managing the food environment

- quieting emotional eating

- preventing relapse

Let’s get started with the first weight loss fundamental.

Calories In, Calories Out

If I asked you to tell me in simple terms why someone is in debt, what would you say? Admittedly, finances can be complicated, but let’s cut to the core of it: people are in debt because they spend more money than they earn. They may spend too much, earn too little, or both.

By comparison, obesity is also a complex condition we can explain in simple terms. We gain weight when we absorb more calories than we burn. We lose weight when expend more calories than we consume. Like debt, many factors influence the calories-in-calories-out equation. Our genetics are certainly a factor, but rarely can we isolate one gene that makes us gain weight. Instead, a combination of genes may impact our physiology and our response to obesity-promoting environments. Even the bacteria in our guts may influence appetite or how efficiently we use the calories we consume.

Although not likely, it’s possible to lose weight eating doughnuts for breakfast, white-bread bologna sandwiches for lunch, and ice cream for dinner. As long as the calories you absorb from these foods are less than the calories burned, you, and your not-so-happy digestive and circulatory systems, will lose weight. That’s one reason the discussion about which diet is best (Atkins, Paleo, South Beach, Zone, etc.) isn’t so important. Calories matter more than the source of those calories.

A multi-site study published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that two-year weight loss did not differ among people who followed four different reduced-calorie diets. Over 800 subjects were randomly assigned to eat one of the following:

- a low-fat/average protein diet

- a low-fat/high protein diet

- a high-fat/average protein diet

- or a high-fat/high protein diet

Their carbohydrate intake was 35 to 65 percent of the calories they consumed, depending on the combination of fat and protein. Each participant’s diet was set 750 calories below what he or she needed to maintain weight at the beginning of the study. Not only was weight loss similar between groups, their hunger and levels of satisfaction were the same with each diet.

These results, along with other studies, suggest there is no single, optimal diet for weight loss. This is great news for people who want to lose weight, because you can choose from a variety of nutritional practices, based on your own preferences and lifestyle. Here’s the most important question to ask:

Is the reduced-calorie diet I want to follow both healthy and sustainable?

If your answer is, “yes,” then I encourage you not to call it a diet. Being on a diet sounds like a short-term project. Instead, I hope you’ll learn to eat in a way you can continue for the rest of your life. Think of it as your eating style.

Next week, we’ll get into some very practical advice on foods to eat.

Come back each week for more healthy weight loss advice from Dr. David Creel.

7 Wackiest Fad Diets

Do you find yourself longing for a return to the health and vitality of your salad days without the need for literal salad days? The best way to lose weight healthfully is with a gradual lifestyle change to a balanced diet and regular exercise, but where’s the fun in that? These fad diets promise mostly speedy results with little or no exercise, and we will eat our hats if they actually work.