Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Relapse Prevention, Part I

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Batter Up

Weight management is unlike many disciplines in the medical field. When a surgeon operates to remove a gallbladder, the operation is almost always successful. When you take an antibiotic for an infection, you usually get better. When you wear a cast, the bone generally heals. Weight management is more like baseball than medicine. If you’re a good major league hitting coach, your players may get a base hit three out of ten times. Your hitter may only hit a home run once every 20-30 at bats. Like hitting a 90-mile per hour fastball, weight management is hard. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program of studies that includes ongoing assessment of weight. One study from data including over 14,000 people sheds light on how difficult weight management can be.

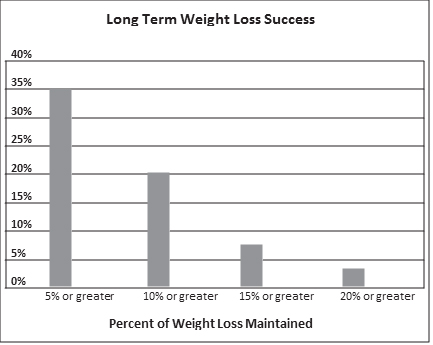

The figure below shows the percentages of people able to lose weight and keep it off for at least one year. As you can see, losing and keeping off 5 percent of weight (a 12-pound weight loss if you weigh 240 pounds) happens for just over one-third of people. This is sort of like hitting singles. The probability of losing and keeping off 20 percent of your body weight (48 pounds if you weigh 240 pounds) is similar to the average professional baseball player’s chances of hitting a homerun at any given at bat — 4.4 percent, or 1 out of 23.

One big problem with weight management is that most of us want to hit a home run; we forget that singles matter. Additional research tells us that a 5 to 10 percent weight loss improves health, helps prevent diseases like type 2 diabetes, and improves other health conditions such as high blood pressure.

It’s important to point out that the NHANES data don’t differentiate between people who had bariatric surgery and those who lost weight without it. However, during the time of the study only about one out of every 2500 people had bariatric surgery, suggesting almost all these data relate to people who chose not to have surgery.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery is much greater than this, but those patients also risk short and long-term complications. In addition, most bariatric surgery procedures aren’t appropriate for people who have less than 75 pounds of excess weight (gastric banding procedures are exceptions and can be performed for people with various medical conditions who are 30 to 40 pounds or more overweight).

The following section on relapse prevention isn’t about hitting home runs or being happy with singles. Instead, I want to explore your approach to hitting with questions such as these:

- Can you keep your head in the game even after consecutive strikeouts or making an error in the field? That is, how do you handle holiday mishaps without falling back into old habits for an extended period of time?

- What is your approach to vacations, eating chocolate, or getting back on track after a binge?

- Do you continue to exercise even when you’re struggling with your eating?

You may hit homeruns with the amount of weight you lose — or you may hit singles. The important part is staying in the game without giving up, and continuing to focus on your health while balancing other parts of your life.

As previously discussed, bariatric surgery is a bigger bat, so to speak, and only certain folks should use it. Surgery is not better in all cases, and many of you will be using a smaller bat. However, all great baseball players have common characteristics to their swing, no matter what size bat they use. Along those same lines, we need certain attributes for successful weight management.

Check Your Weight, AND Keep Your Eye on Behavior

Research shows that frequent weighing helps prevent relapse. People who keep weight off tend to step on the scale at least weekly. By comparison, those who are unsuccessful with their weight often view the scale as a tripwire that punishes them if they take a step in the wrong direction. They weigh when they know they’re following a safe path, but avoid the scale when they veer a little off course.

In previous posts we covered ways to adjust our thinking in order to view the scale as a dependable friend giving us positive feedback to help correct our course. I encourage each client to use these skills and eventually reach a point of weighing regularly, especially when the body reaches a natural plateau after weight loss.

Even though regular weighing is extremely helpful to prevent relapse, weight doesn’t tell the whole story about progress. For example, a 40-pound weight loss can represent different things for different people, based on starting weight and weight-loss treatment. If a 400-pound man has gastric bypass surgery, loses 40 pounds, and then has a six-month weight plateau, he has probably relapsed. His lack of expected weight loss tells us there are problems. He probably returned to unhealthy eating patterns that might include high-fat snacks, sweet tea, or fast food.

Let’s compare this surgery patient to a woman who is less overweight, lost 40 pounds, and kept it off for three years without bariatric surgery. In her case, the weight plateau is probably a sign that she’s following a healthy eating plan and regular physical activity — even if she’s still 30 pounds overweight by medical definition. Her metabolism and appetite have adjusted to her new weight, so the plateau isn’t necessarily a sign of unhealthy habits.

As the previous figure suggests, most people who lose weight are still considered overweight or obese by body mass index (BMI), a simple weight to height calculation. It’s crucial for you to remember that maintaining weight loss has many health benefits even if the charts still indicate you’re overweight. Just because your weight plateaus at a number higher than you desire (or a BMI chart recommends) doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong or you relapsed into old behavior. The only way to truly evaluate how you’re doing is to look at what you’re doing.

We can rarely define weight-related relapse with one behavior, so you need to look at many daily decisions when examining your lifestyle.

Comparing eating behavior relapse to drug abuse gives us another way to look at this concept. With drug use, an addicted person relapses when he returns to using drugs. It’s usually black or white — he’s either clean or relapsed. Although the addict often starts behaving in ways that predict relapse, we define relapse with specific behavior: He’s using again.

Weight management is different because the behaviors aren’t black and white. Eating cheesecake can be part of an overall healthy eating plan — or it may be one of many signals that someone has relapsed into old patterns. For successful long-term weight loss, you need to maintain a variety of healthy practices such as regular exercise, portion control, balance between food groups, and limiting calorie-dense foods.

Frequent weighing is a simple and helpful way to create a centerpiece for your relapse prevention plan. But remember, we weigh ourselves to become more aware of our behavior. And behavior should be the focus of our plan to get back on track when we struggle.

Identify and Plan for High-Risk Situations

If you have an important work-related meeting at eight o’clock in the morning and a snowstorm is supposed to hit your area at 4:00 a.m., what would you do? If you’re planning a long car trip, how do you prepare? What if your child complains of a stomachache before bed? Experienced snowy weather residents, veteran travelers, and wise parents understand each of these situations is high-risk for something undesirable to happen. Being on time for a meeting may require getting up early to shovel the driveway and allow for a longer commute. An experienced traveler packs in advance and has the car serviced before a long trip. When a child complains of stomach problems before bedtime, parents soon learn to prepare for a possible upchuck in the middle of the night. (My mother sent us to bed with “puke sacks,” and my wife’s family used bowls, which makes me leery of eating soup when visiting them.)

My point is, most of us know how to identify, plan, and prepare for high-risk situations in our lives. We know what works and what doesn’t. Based on experience, we change our approach over time.

When it comes to exercising and eating the right foods, high risk situations are all around us. What events jeopardize your weight management goals? Weekends, vacations, holidays, celebrations, stress, and any life transition can lead to lapses and even full-blown relapses. Think about the last time you lost weight and then began regaining it. What was going on? If similar things happened again, how could you prepare beforehand and how could you handle things differently?

Some high-risk situations are small, day-to-day events that throw us off course. Matt told me he had an issue with overeating cashews at work. He always kept a can of nuts in his desk drawer in case he worked late or missed lunch. But during normal work hours when he did have lunch, the cashews presented a problem. When things got hectic or he felt a bit hungry he’d help himself to “just one handful.” That small snack turned into mindlessly picking at cashews all afternoon until the entire can was empty. He could keep other foods at his desk without a problem, just not cashews. He said cashews weren’t a problem at home. But the combination of his work environment, plus cashews, created a perfect storm for Matt.

Other people may be overcome by shopping when hungry, having homemade cookies at home during a stressful time, driving with snack food in the passenger seat, and a dozen other scenarios that can be avoided by planning ahead.

Other high-risk situations are unavoidable. Only a hermit could totally avoid social events that challenge healthy eating. Still, we need to anticipate problems whenever possible and have a plan to stay on track. Every stressful event you prepare for is helping you develop skills to handle future situations, even the toughest ones. The longer you practice those coping behaviors and the more natural they feel, the less likely you are to fall apart when your life changes.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Use B-SMART Goals for Weight Loss Success

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

The B Is for Behavior

Outcome goals are king in weight management, but they shouldn’t be.

I will lose 30 pounds and keep it off

I’m going to get off my blood pressure medication.

This year I will run a 10k race.

There’s nothing wrong with these goals. Losing weight, getting off medication, and fitness events are all good things. But if this is the extent of goal setting you may fall short. Each outcome goal we set should be coupled with specific actions to support the goal. These actions are called behavioral goals. Although a baseball coach may have a goal to win the championship, nothing is going to happen without specific behavioral goals for the team. Likewise, if your desire to lose 30 pounds isn’t coupled with clear-cut behavioral goals, it probably won’t happen. Action-oriented goals for weight management can include anything that directly or indirectly impacts weight:

| Self-weighing | Food journaling | Weighing/measuring food |

| Shopping from a grocery list | Meal planning | Tracking steps |

| Going to the gym | Walking the dog | Rating/hunger |

| Sleep | Time spent watching TV | Alcohol intake |

| Dining out | Playing in a sports league | Eating less at night |

| Eating at the table | Walking on lunch hour | Prayer habits |

| Meditation | Journaling thoughts | Batch cooking |

| Seeing a therapist | Taking an exercise class | Attending a support group |

Specific (S) and Measurable (M)

Setting criteria you can measure is an excellent way to find and define specific goals. People frequently tell me their weight-related goals are to exercise more this month, eat better, or get back on track. What do these mean? One more step, one more bite of broccoli? Is getting back on track just a frame of mind or an actual set of behaviors?

Suppose you want to focus on increasing vegetables, eating breakfast, and reducing your calorie intake late at night. Specific and measurable goals could be:

- I will eat two cups of vegetables at least four days this week.

- I will eat something before 9:30 a.m. six days this week.

- I will track the calories in my snacks after dinner and stay under 300 for at least five days this week.

If your goal involves physical activity, take a few minutes to think about what you’ll do, how often you’ll do it, and the amount of time you’ll spend. Also consider factors that affect your activities, such as thunderstorms (if it’s raining I will walk on the treadmill instead of riding my bike outside). For example:

- This week I will walk outside or on my treadmill before work for at least 30 minutes.

- I will go to Zumba class on Saturday.

- I will wear my Fitbit every day this week and reach 10,000 steps on at least five days.

- I will walk on my lunch hour on Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday.

Generally speaking, the more specific and detailed the plan, the better. On one occasion, however, I got more information than I bargained for. Marie told me her plan was to continue doing resistance training three times per week with rubber tubing. I asked her what days and times she would work out and which exercises she would do. Marie told me she waited until the evening to do her exercises because that’s when her husband was home and he liked to watch her workout. Straight faced she added, “He likes it because I work out in the buff.” Since the success rates for maintaining marriages and fitness programs aren’t so great, I supported this plan. I decided to forego my usual questions about exercise form and technique and assumed she was working all her major muscle groups. Since that day, I always feel the need to wipe down rubber tubing before I use it at the gym!

A = Attainable

This step of goal setting is where things often fall apart. In our minds we know what’s recommended, ideal, or possible — and so we set goals accordingly. We ignore that the planets would have to align in perfect order to create the circumstances for us to achieve these goals. If you typically eat three vegetables per month, immediately transitioning to five servings per day is highly improbable. Even though 10,000 steps is recommended, increasing from 4,000 to 6,000 may be more realistic in the beginning. This approach worked well for Janet.

When Janet told me she was wearing her pedometer faithfully, I didn’t really believe this was true. I couldn’t imagine she was truly walking only 900 to 1,200 steps each day. She must be only wearing it a few hours during the day; maybe the pedometer is a lemon or the batteries are bad. The average American, who is notoriously sedentary, accumulates five times as many steps. Although she was overweight, Janet wasn’t disabled in any way. Her knees seemed to be in shape to handle walking and she didn’t complain of any other limitations. Janet would have to increase her walking by a factor of 10 to reach the recommended 10,000 steps per day.

When she described her lifestyle things began to make sense. She was a busy account manager at her firm but worked from home. She parked at her desk all day, only getting up to go to the bathroom or kitchen, both near her office. When she finished working, she would sometimes run an errand or do some light house cleaning, but that was about it for physical activity. In the evening Janet often returned to her computer to finish work, fall into the abyss of social media, or play solitaire. She and her husband would also watch an hour or two of TV. She’d never been an exerciser but was open to the idea of becoming more physically active. She had recently lost weight without exercise but knew her chances of keeping it off were not good unless she moved more. Janet also wanted to feel better. She felt sluggish. Like a toddler who can’t sit still, her body yearned for movement.

She started with a goal of 3,000 steps each day, which she achieved easily just by getting out of her chair more during her work day and doing a daily errand that required some walking. After several weeks of this, we set a goal of 5,000 steps per day at least five days per week. She was able to accomplish this on the weekend by doing yard work and more housecleaning. On work days she decided to walk for 20 minutes when she took a break for lunch. Janet enjoyed the concrete aspect of tracking her steps and the challenge of reaching her goals. She was also motivated by the fact that she felt more energetic, could concentrate better throughout the day, and slept soundly at night.

sometimes they simply keep us from sliding backward.

The next goal was to reach 8,000 steps at least three days per week. Again, the weekends were easier. Janet added a 40-minute walk to her already established weekend routine. She also began taking a 40-minute walk with her husband on Wednesday or Thursday evenings. Janet and I continued to set progressive goals and after six months she took 7,000 to 11,000 steps at least five days per week. We didn’t quite reach 10,000 steps every day, but we were close. Janet was now walking in place during long conference calls and enthusiastically signed up for her first 5K. She was always excited to tell me about her new step record, which finally hit 15,000 per day, thanks to a 40-minute Saturday walk plus a trip to the flea market.

Setting attainable goals requires setting aside our should thoughts and all or nothing thinking and focusing on progress, not perfection. Goals need not be like a light switch we flip on and off, going full force and then regressing back to nothing. Instead our goals can be more like a dimmer switch that’s always turned on, sometimes shining brightly and at other times softly illuminating. No matter the intensity of our goals, the act of setting them helps keep us mindful of long-term objectives. Each month, week, or day, consider what you can realistically accomplish. During a busy week of travel, you may focus on maintaining your weight by getting to the hotel gym three times and avoiding dessert and alcohol when dining out in the evening. When you’re at home with better control of the environment, you can turn the dimmer switch up to more frequent exercise, lower-calorie food preparation, and a greater variety of vegetables than were available while traveling. The famed Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson put it this way: “Don’t judge each day by the harvest you reap but by the seeds that you plant.”

“T” Is for Time Frame

Short-term and long-term goals are both important, especially when we focus on losing a substantial amount of weight. Losing 30 pounds means you have to create a 105,000 calorie deficit over an extended period of time. Unfortunately, once you lose weight, the hardest part of weight management awaits you — maintenance. To keep the weight off you’ll need to sustain most of the behavior that helped you lose weight in the first place. A 30-pound weight loss from conventional treatments may take six months to a year as you consistently burn more calories than you consume. Therefore, you’ll need to set many short-term goals along the way. You will have to manage your weight, just as supervisors manage a business, frequently evaluating success and failure while readjusting your goals and objectives.

A common error in goal setting is to have long-term goals without setting enough goals for the short run. In some circumstances I discourage long-term goals, such as overall weight loss, until a client has a chance to set short- term behavioral goals and see how much work weight loss requires. A healthy weight is the weight you reach when you do healthy things over an extended period of time. This can’t be determined by a chart, a formula, or even the weight you felt great at 20 years ago. You’re setting yourself up for disappointment if you set a weight goal you can only reach if you behave in a way that isn’t healthy or realistic to sustain.

That’s why specific shorter-term goals with a wait-and-see approach are often more effective. You’ll get immediate returns by feeling better and becoming more fit, instead of holding onto a distant “pie in the sky” goal. The idea of that goal may still exist, but it won’t be your main focus.

encourage you to be diligent about frequently evaluating your progress.

Although no secret formula exists for timing your goals and reviewing progress, I encourage at least weekly goal-setting sessions during the early stages of weight loss. Once a week you can either meet with a professional, a peer, or yourself to review how you did with the previous week’s goals. If you achieved them, how did you do it? If you didn’t, why not? Were your goals unrealistic, not specific enough, or maybe not that important to you? Or was it a problem with execution? Do you need a more specific action plan, such as making sure you go to the grocery store over the weekend and stock up on food to cook healthier meals? Perhaps your goal of exercising in the morning will only work if you have a plan that helps you get to bed earlier the night before. Did you put everyone else’s needs in front of your own? You might reevaluate your thinking.

Over time, accomplishing these short-term goals may lead to habits you follow without thinking. When this happens, weight management becomes easier. However, because obesity is a chronic, relapsing condition, I encourage you to be diligent about frequently evaluating your progress. If your behavior starts to drift in the wrong direction, you can quickly identify the problem areas and use goal setting to help you get back on track. This may be as simple as weighing daily and observing your weight graph once a month to spot trends. Some of my long-term clients, even if they’re doing well, return to the office every month or two for exactly this reason.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Disputing Your Dysfunctional Beliefs

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

I hope you agree that it’s a good idea to change thoughts and beliefs that stand between us and weight management. But how can we do it?

The first thing to remember is that thinking is automated. If we do nothing, we continue to think and behave the same way. Changing our thoughts requires practice and persistence. Earlier you read about the ABCs — activating events that lead to beliefs, followed by a consequence, such as an emotion.

One way to practice changing thoughts is to add a D to our ABCs. The D stands for dispute. What are we disputing? We are disputing beliefs that lead to undesirable reactions to situations. Here’s an example:

Activating Event:

Joanie vowed to begin eating better but a co-worker brought her wonderful lemon bars to work on Friday. Joanie ate four of them.

Belief:

I totally blew it today — I have absolutely no self-control! Since today was a disaster, it doesn’t really matter what we eat for dinner. We might as well order a pizza with extra cheese tonight — and go ahead and add those dessert bread stick thingies too. I can always get back on track at the beginning of next week.

Consequence: Frustrated with herself for not handling the lemon bar situation well, Joanie feels hopeless about managing day-to-day food choices. She loses focus on her goals and overeats for the rest of the weekend.

Dispute:

Let’s look at Joanie’s dysfunctional beliefs and how we can dispute them. Thinking she’d already blown it for the day and had absolutely no self-control are perfect examples of all-or-nothing thoughts that have a tone of failure and hopelessness. The idea that she should go ahead and eat more because she ate too much earlier is emotional reasoning. After having her wallet stolen, would Joanie withdraw money from the bank and set the money on fire? If she accidentally dropped a glass and it broke on her kitchen floor would she break more dishes, because ten broken glasses are the same as one? When a patient describes it-doesn’t-matter feelings, I’m often reminded of the lyrics from my favorite Kenny Wayne Shepherd song. It’s like:

…blue on black, tears on a river, push on a shove, it don’t mean much… whisper on a scream — doesn’t change a thing.

That’s how we feel when emotions run high. But feelings are not reality. The extra calories we eat after a snacking mishap aren’t the same as a whisper on a scream. They matter. More importantly, these beliefs interfere with your ability to handle slips. Thinking this way ultimately continues the diet-relapse cycle. Just as setting money on fire after getting your wallet stolen is illogical, so is continuing to make poor food choices just because you made one poor choice.

The belief I can always get back on track at the beginning of next week is a classic procrastination strategy that gives Joanie permission to think and act irrationally because she’ll start fresh at some time in the future. The procrastination thought helps her feel a little better because she has an obscure plan to get back on track. Procrastinating gives Joanie a little psychological space to forget about messing up earlier, so she can eat the pizza and dessert breadsticks without overwhelming guilt. But if Joanie took time to think rationally about her situation, she’d realize that going off the rails for the entire weekend leads to feelings of regret. So how could Joanie think about the lemon bar incident? Consider these ideas:

Disputing “I’ve already blown it for the today.”

Although I’m not happy about eating the lemon bars, I haven’t ruined my day. That extra 600 calories is a minor contributor to my weight, especially if I eat reasonably the rest of the evening.

Disputing “I have absolutely no self-control.”

That’s not true. I have a lot of self-control in many areas of my life. I often refuse buying things to stay within our budget. I don’t tell people off every time I have a negative thought about them, and when it comes to food, I’ve been making good choices more than not-so-good ones for weeks.

Disputing “It doesn’t matter what I eat for dinner, we might as well order a pizza.”

In actuality what I eat the rest of the evening does matt it only feels like it doesn’t. Making better choices the rest of the day will help me recover from slips more easily in the future. Possibly, Joanie really wants the pizza and dessert breadsticks for dinner. If that is the case, fine, but let that decision arise from rational thoughts that allow her to fully consider the pros and cons. The pizza meal should be her conscious choice, not an emotional reaction.

Disputing “I can always get back on track at the beginning of next week.”

Hold on, that isn’t a recovery plan — it’s a sneaky way of giving myself permission to stay on a path I’ll regret later. What can I do right now to get back on track? I’ll take a five-minute walk and think about the best way to handle food choices for the rest of the day.

The last part of the ABCs (and now D), is to add E. E reminds us to evaluate. At this stage, we examine how facing dysfunctional beliefs about weight management will change our emotions, and then alter our behavior in a positive way.

Did thinking different about a situation help calm your feelings?

Did you behave in a different way, with less drama and a better outcome?

If you’ve already begun reacting to situations in a more sensible, thoughtful way, then the thought changing exercises are working. If not, don’t feel discouraged. Take time to examine which thoughts are still holding you back. Remember that emotions are not a switch we turn on and off. Even if we begin thinking differently, our emotions can linger awhile. Just because you recognize something isn’t true doesn’t mean you immediately stop reacting emotionally to the initial thought. Combining the thought restructuring exercises above with deep breathing or moderate exercise may help settle your emotions.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: 8 Negative Thoughts that Interfere with Weight Loss

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

One of the first steps to changing your thinking is to identify thoughts that get in your way. Categorizing these irrational beliefs can lead to building a shortcut that will help lead to functional thinking and healthier behavior. Here are seven types of negative thinking that can interfere with weight loss.

1. All or Nothing Thinking

Did you go to bed as a late-night snacking bug and hope to awaken in the morning as a die-hard dedicated dieter? Motivation, drive, and excitement can be instrumental in helping us accomplish important goals such as losing weight. But when we look at things in a polarized way, we end up repeating cycles of weight loss and regain.

To learn more about how to combat this pattern of thinking, read Avoid “All or Nothing” Thinking.

2. Filter Focus

Some people filter out accomplishments and focus only on their deficiencies, especially those related to weight. An example would be ignoring the two pounds you lost, while focusing on a package of cookies you ate this morning. This viewpoint leads down a road of frustration and hopelessness, paved with the perceived tragedy of many failures. Don’t get me wrong, we do need to understand and evaluate our mishaps, but only if we also enjoy our positive attributes and success.

Learn how choosing to mainly focus on the positive aspects of life changes your outlook on every situation, the people you encounter, and yourself, in The Problem with Filter Focus.

3. Mind Reading

Mind reading can obstruct weight management by causing anxiety and concern over what others think about us. Thinking this way can result in self-imposed pressure to prove something to a boss, sibling, spouse, or co-worker. As a result, we may eat to help relieve the stress caused by these feelings — or we may lose focus on weight-related goals.

Mind reading can directly impact health behavior if we make assumptions about what others think about our size, what we eat, or our competence using exercise equipment at the gym.

Learn how trying to be a mind reader can obstruct weight management by causing anxiety and concern over what others think about us in Stop Trying to Be a Mind Reader.

4. Catastrophic Predictions

The idea that you’ll never lose weight if you don’t do it now is a good example of a catastrophic prediction. This way of thinking creates enormous pressure to change. Although this pressure can yield results in the short run, it doesn’t work well as a long-term perspective. A now-or-never mindset builds resentment and is emotionally exhausting. You may believe that putting intense pressure on yourself to change NOW will eventually lead to healthy habits. But our minds don’t work that way.

5. Labeling

In most instances, labeling is a poor way of explaining our behavior. We are unintentionally reasoning our way out of a solution. In other situations, using labels can be a copout. When you label yourself stupid, lazy, disorganized, or lacking willpower, you’re saying you can’t change — and that lets you off the hook for managing your weight.

Read how Catastrophic Predictions and Labeling Won’t Help You Lose Weight.

6. Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning permeates many areas of our lives, including relationships, career, self-image, and certainly weight management. Having a strong emotional reaction each time you see the scale move in the wrong direction may cause a surge of negative emotions that leads to irrational thinking. Maybe you vow to eat nothing all day forgetting that each time you try this it ends in disaster. Or perhaps you feel strongly that you’ll never succeed and, as a result, you stop trying to eat right or stay active.

Read The Problem with Emotional Reasoning.

7. Demands

If you want to manage your weight long-term, “shoulding” yourself is not the best strategy. It may actually prevent us from doing what’s important. Even if you have short-term success guilting yourself into action, this won’t be effective in the long run. Even if it worked, who wants to feel guilty or pressured all the time? Telling yourself you have to do something strips away your perception of freedom and can lead to feeling disgruntled and even angry.

If we want to make lasting behavior changes and feel good about it, we need to stop talking to ourselves that way. Be nice to yourself. A simple change in words can make all the difference.

Read Why Making Demands on Yourself Won’t Help You Reach Your Goals.

8. Rationalization

Instead of blaming themselves for everything, some people blame others or their situation in life. Sometimes we come up with complicated explanations for our behavior so we don’t have to take responsibility for it. Yes, we do live in a culture that promotes weight gain and inactivity, but we still have choices. Some rationalizers are the defensive, angry types and others are intellectuals, debating like high paid defense attorneys. Some of us have spent years “spinning” the responsibility of our actions to make it someone else’s fault when we can’t reach our goals. Always shifting the blame bogs down our ability to achieve health goals.

Read Rationalization — It’s Not My Fault.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Are You a Weight Management “Dry Drunk”?

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Have you ever tried to fake having a good time? Even if it’s only for a few hours while shopping for window coverings with your wife or walking through an antique car show with your husband, it’s hard to pretend you’re having fun when you’re thinking about a dozen other things you’d rather be doing. Now think about something more long-term, like a job or marriage. If your head isn’t into your work or a relationship, you can’t pretend things are wonderful day after day. Your behavior will eventually reveal your discontent.

Weight management is the same. If your thoughts, emotions, and behavior are not in sync you won’t be able to fake your way through it by using willpower or ignoring your true feelings year after year — that just won’t work. How long will you be able to eat healthy if your thoughts are “this diet is for the birds, I wish I could eat real food” or “I just want to eat the way everybody else eats?” Alcohol treatment circles like Alcoholics Anonymous have a name for this type of disconnect between thoughts and behaviors: a dry drunk. It goes something like this:

For many years Pete couldn’t control his drinking. He drank almost every day, much to his wife’s chagrin. Occasionally he white knuckled it for a day or two and didn’t drink, mainly to show his wife he had no problem and could stop anytime he wanted. He sometimes missed work due to hangovers and oversleeping. Recently things escalated as his boss wrote him up for skipping work, and two days later he received his third DWI and went to jail. This time, the judge revoked his driver’s license. Needless to say, Pete’s wife was not happy, knowing she’d be responsible for driving him to and from work and he wouldn’t be able to help take the kids to events. She let him sit in jail for two nights before bailing him out and then gave Pete an ultimatum — quit drinking or the marriage is over.

Not only was Pete getting tough love from his wife, the judge ordered him to alcohol treatment. Getting his license back was possible only if he completed treatment and had clean random urine screens for a prolonged period of time.

How did Pete react to these humiliating events? He got angry. First of all, the cop had no right to pull him over; he was driving fine and just had a broken tail light. From his perspective, no one was in danger. His wife was overreacting as usual — even her own mom agreed she could be too emotional. The judge, well, he was ridiculous. Pete, in his mind, was not like all of the other losers who appeared in court.

Besides the anger, Pete was jealous of his buddies who could seemingly drink without being harassed by a badgering wife, an uptight boss, and overzealous cops looking for a reason to lock people up. But he felt backed into a corner with no other option but to stop drinking so, reluctantly, he did. At the court-mandated AA meeting he sat with arms folded in the back of the room, feeling sorry for himself.

Pete was what we call a dry drunk. Dry in the respect that he wasn’t drinking, a drunk because he still had the thinking patterns of an alcoholic in the throes of denial: a toxic combination of blaming others and rationalization.

What happens with dry drunks? Usually they begin drinking again because their thinking patterns and attitudes have not changed. At some point, a person with Pete’s frame of mind glorifies the freedom to drink while ignoring the potential consequences. He takes the first sip and then finishes the drink. Since he’s already blown it, he has another. Not only has he already screwed up, but the effects of the alcohol are setting in and that feels good, so he keeps drinking, not for one night, but tomorrow, too. This lapse leads to a complete relapse into old patterns of behavior, all but destroying his confidence to give recovery another attempt.

But there is another possibility. In some cases, a dry drunk will change his thinking patterns and remain sober. Possibly, Pete will begin to notice his mind is clearer, he has more energy, and is getting along with his wife better now that he’s sober. He starts to remember why they got together in the first place. He is “present” with his kids and sees what he’s been missing all these years. His 9-year-old daughter is so smart and seems to enjoy having grown-up conversations with him. Shooting baskets with his 11-year-old son is much more rewarding than sitting on the couch drinking and watching TV. He hears the news about a drunk driver killing an entire family in an accident and starts to accept that his behavior could have led to the same terrible result. His buddies’ lives aren’t as great as they once seemed; their marriages and relationships with their kids leave much to be desired. If his positive thoughts about sobriety translate into changed behavior, it’s feasible, even likely, that Pete will stay sober.

People cannot easily overcome alcoholism, and Pete’s scenario shows that staying sober only happens when we align our thinking with our behavior. Changing both thoughts and behavior takes a lot of courage and hard work.

The same goes for managing weight. Over the years, I’ve encountered many weight management dry drunks. These folks follow a diet for a while, but what they really want is to eat whatever they want, whenever they want. Following a diet is akin to serving a prison sentence, and they feel they’re “doing time” for a crime they didn’t commit. They tell themselves, or other people tell them, they must follow a certain eating and exercise regimen. Certain foods are off limits and their choices are non-negotiable.

This constant oversight by the food police, whether themselves or others, can lead to sadness, anger, and jealousy. These feelings are often directed at friends or family members who don’t have to struggle with weight, despite their poor diets and little exercise. Typical thoughts include:

“I don’t know how she stays so thin eating like that—it isn’t fair!”

“I can’t have any pie because this miserable diet doesn’t allow it.”

“I have to get on that boring treadmill to burn more

calories.”

“What’s the point in going out to dinner if I can’t eat food I like?”

Some of these weight management dry drunks are distressed and saddened by the notion that they can only lose weight by giving up something they love so much — delicious food. Along with these thoughts comes the reality of what will happen if they don’t lose weight:

“My doctor said I can’t have knee surgery until I lose 50 pounds, and I can’t stand this pain.”

“I avoid any building that requires walking up stairs and I’m afraid if I fell I couldn’t get up—so I have to lose weight.”

“I have no choice because I can’t bear the thought of someone having to care for me when I get older. It would take two or three people just to lift me.”

Like Pete, these people feel backed into corners. They don’t really want to change their behavior and often think about the misery associated with dieting, exercise, and paying attention to their weight. They just want to live a “normal” life, but the threat of bad things to come will keep them on track for a while. Yet their heads are not in the game. They are reluctantly meandering away from bad things instead of running toward something they truly desire. Like a child who behaves only to avoid punishment, they are primed to rebel. They secretly look for a way to cheat the system or deceive those who are seemingly in charge.

After losing 20 pounds, Debbie hit a weight plateau. In fact, her weight was starting to creep back up ever so slightly. As we talked about this, she told me she was starting to “rebel.”

“That’s an interesting way to put it,” I said. “Tell me what you mean.”

“Well, I know I have to follow this diet, and knowing I have to makes me want to do just the opposite,” she said.

“Who said you had to follow the diet?”

“Well I guess no one actually said that.” She broke eye contact and looked down at the table.

“Do you feel like our team is pressuring you?”

She leaned forward, placed her elbow on the table, and rested her head in her hand. “No, it’s not you guys,” she said as she ran her fingers side to side above her eyebrow.

“Debbie, you can do whatever you want. You’re free to get up right now, head to Burger King, and order everything on the menu.”

She giggled and then sighed. “I guess you’re right, but it doesn’t feel that way. I tell myself I have to do this. The more I tell myself I have to follow a diet and exercise, the less I want to do it. I start to rebel against my own thoughts. Am I crazy?”

Debbie was not crazy, but she was right about feeling rebellious because of her own thoughts. She made demands on herself that caused her to feel as if she didn’t have a choice. Her compliant self was wagging a finger at her alter ego and saying, “You must eat this and you can’t eat that.” In response, the part of her that didn’t like being told what to do was feeling the urge to flip her the bird, take her I’ll-show-you attitude to a convenience store, and buy a candy bar and a regular, not diet, soda.

This back-and-forth type of thinking is not only exhausting, but can have a powerful effect on attitude — and our attitudes obviously impact our long-term behavior. The only way someone loses weight is to change behavior. We cannot educate our way to a healthier body, think our way to success, or pay our way to weight loss. In the end, it boils down to behavior: The types and amounts of food we eat and the physical activity we perform.

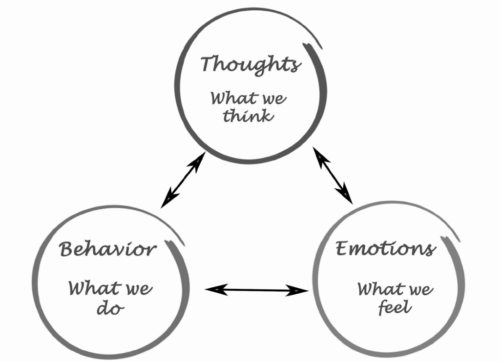

But focusing only on behavior is short-sighted when it comes to long-term weight management. Since most dieters already know about the behavior needed to lose weight, it makes sense to explore how our thoughts and feelings are connected to those behaviors. The following illustration shows that our thoughts, feelings, and behavior are connected, each influencing the other. The arrows between the three concepts are bi-directional which means that:

- Thinking can impact our behavior, and

- behavior can change our thinking.

- Thoughts can change our feelings, and

- our feelings impact our thoughts.

- Our feelings can affect behavior, similar to how

- behavior impacts our feelings.

While working to become a better weight manager, you’ll find it important to identify which of these connections most often gets in your way. Do you need a more structured behavior plan to improve your confidence? Or perhaps your plan is fine, but emotions derail your progress. Perhaps your thinking is the problem — how you interpret life situations leads to stress eating and abandoning your exercise routine. Pete and Debbie showed us how thoughts, feelings, and behavior interact to shape our attitudes .

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: How Our Environment Affects Our Weight Loss Efforts

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

After having twin boys, Ted and Linda hoped to become pregnant again. Neither of them hid their desire for a little girl. After five years of trying, they accepted that another child wasn’t in the cards for them. Once they reached their 40s, Ted and Linda were enjoying their teenage boys and had long given up on trying to increase the size of their family. Then they received amazing news — Linda was pregnant — and they were having a girl! They named her Emily, a name they picked out ten years earlier.

For the first five years of her life Emily lived in a fast-paced home, often eating on the run and snacking on junk food like her brothers. She accompanied her parents as they traveled out of town to watch the boys play tennis and baseball. During these trips everyone ate fast food and consumed not-so-healthy snacks. Soon after Emily’s sixth birthday her brothers moved away to college. Emily and her family no longer traveled to sporting events, and their home life became much calmer. In essence, Emily suddenly became an only child.

I met Emily four years after her brothers moved out of the house, when she was ten and the family no longer needed to eat on the run. Although the always-starving teenage boys hadn’t lived there for years, Emily and her parents still ate out frequently and kept the same types of food in the pantry. As a result, Emily had become quite overweight.

Her concerned parents and pediatrician enrolled Emily in our children’s weight management program. Although Emily’s mom came to the initial consultation, her work schedule and frequent travel made it difficult for her to attend regular sessions. Since her father Ted did the shopping, meal planning, and cooking as a stay-at-home dad, our staff worked with him in our efforts to help Emily lose weight. We soon realized Dad’s habits and perspective were a big part of Emily’s struggle with her weight. For instance, he regularly purchased large bags of tortilla chips, mainly for his personal late-night snacking. Because Dad wanted to keep snack foods in the house for himself, the conversation turned to Emily’s motivation and self-discipline. Emily respectfully listened to her father and tried to explain she wanted to do well in the program. After her father continued suggesting she could avoid the chips or only have a small serving for her after- school snack, she uncharacteristically snapped at him, “Dad, I have willpower, but I also have arms!”

We can all relate to Emily’s sentiment. The environment in which we live can make or break weight loss efforts. While Emily’s father wanted her to practice restraint and use willpower, Emily knew the environment was more than she could handle. Focusing on a ten-year-old’s willpower seemed a little silly when a more reasonable solution was to modify the food in the pantry. Doing so would also show support for Emily’s struggle.

loss efforts

On the other hand, Emily’s father couldn’t create a perfect environment, nor can you. At some point we all have to stop blaming the environment and using it to excuse our actions — at least according to a client named Marty.

In a discussion group of 12 people, Marty and I were the only men. One evening, as we discussed the challenges of weight management, ten ladies did a nice job of describing how their home environments, workplaces, and fast-paced lifestyles got in the way. Marty sat quietly for the first half hour, but toward the end of our time he began squirming in his chair. Finally, he sat up straight and sighed loudly to let everyone know he had something on his mind. We all looked at the 40-something chemist who’d gained 50 pounds since beginning work at a pharmaceutical company six years earlier. We already knew his long work hours and the addition of two children to his family created a lifestyle conducive to weight gain. We also knew Marty was irritated with himself for gaining weight and even more frustrated that he had to join a weight management group for help. In a previous session he had told us that obesity treatment seemed “stupid” because the solution was simple — eat less and move more. Now we all eagerly awaited his opinion on why weight management was so difficult. He took another deep breath, probably to swallow the four-letter words on the tip of his tongue.

Marty’s frustration showed in his furrowed brow and restless fingers that curled into a fist. “I hear what you’re all saying. But never, not once, has someone tackled me, pinned my arms to the floor and shoved food down my throat. Never! No person or situation makes us do anything — we’re doing this to ourselves.”

Marty had a valid point. Despite our food-centric society, we all have freedom to make choices. Although I’ve heard more than a few troubling stories from my patients about being forced to eat as children, most adults are entirely free to refuse food or eat in whatever quantities they want. Although the environment can limit our options or make certain behavior difficult to carry out, it does not force us to do anything. If we intentionally pay attention to hunger, fullness, our calorie needs, and the nutritional quality of our food, we can maintain a healthy diet despite the availability and ease of obtaining highly pleasurable, unhealthy foods.

But we live in a fast-paced world where it’s difficult to always self-monitor every food decision; to constantly be on alert regarding our calorie budgets and how well we’re sticking to them. Instead of being proactive, we easily get distracted and just react to our surroundings. In most industrialized nations the surroundings are obesogenic — teeming with food and conveniences that promote obesity.

In the United States, two-thirds of adults are overweight or obese, at least partly because of the environment we created. Consistent with human instincts, we tend to make choices based on what’s available, convenient, pleasurable, and socially acceptable. It’s no stretch to say that unhealthy foods are easier to find than healthier alternatives —think restaurants, gas stations, vending machines, sporting events, and the check-out lines of grocery stores.

Adding to the problem, modern technology has engineered physical activity out of our lives. Many of us drive to work and then sit at desks most of the day. We drive home, push the garage door opener, and walk a short distance to the mailbox. Exhausted from our busy-but-inactive day, we spend another few hours relaxing in front of the TV. To change the channel, we push a button the remote control. We even have robotic vacuum cleaners to clean our floors and entertain the cat. We take escalators and moving walkways to get through airports, perhaps to conserve energy for putting our tray tables in the upright position.

Sometimes our environment promotes unhealthy eating and inactivity at the same time. The Indiana State Fair, and most other state fairs, offer excellent examples. In Indianapolis, a long trolley pulled by an enormous John Deere tractor gives free rides around the fairgrounds. This is a helpful service for people with disabilities, but healthy people also jump at the opportunity to save a few steps. The remarkable part of this is that many people go to the fair primarily to sample the food. So a trolley provides transportation to the corn dog hut only to pick you up and take you to another area where you can have an elephant ear, a fried Snickers bar, deep fried macaroni and cheese, or a funnel cake. If you get too hot waiting for the trolley you can purchase a giant cup of lemonade filled with a little fresh squeezed lemon and a fourth cup of sugar. Bottled water is always an option, but it costs almost as much as the lemonade, and besides, it is the State Fair.

This all seems normal, even to those of us in the health field. When I attend large obesity or fitness conferences I like to observe the behavior of attendees. People leave a presentation with many good ideas after hearing a talk on the benefits of decreasing sedentary behavior and increasing patients’ motivation for physical activity. After they leave the room to go to another part of the conference hall, where they will again sit through a 90-minute symposium, they need to go up or down to another floor. When these attendees reach the escalator with a spacious carpeted set of stairs beside it, almost everyone stops walking and rides the escalator. This shows me how persuasive the environment is, even among people who are highly educated on the benefits of healthy behavior.