North Country Girl: Chapter 20 — The 60s Arrive in Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

In 1967, my eighth grade summer, the sixties finally trickled up to northern Minnesota. Up till then, we had existed in our own little insulated pocket of intact families, nosy neighbors, regular church-going, casual drunkenness, and a sincere belief in the virtue of conformity. Children were seen but not heard, teens were just big kids waiting to become adults, God was in his heaven, and all was right with the world.

Somewhere in the South people were marching for civil rights. Duluth had virtually no black people. We had a few grizzled Indians hanging around the liquor stores, waiting to buy booze for teen-agers in exchange for a few bucks or a can of beer. We had a handful of Jewish families, who were regarded suspiciously by my mother, although she had jumped at the chance to dump her two youngest kids in a half-day preschool at the Jewish Educational Center, where Lani, and later Heidi, learned to play the dreidel and build Sukkot tents.

Men were burning their draft cards in Berkeley and New York City; Walter Cronkite led off the news with stories of the war in Vietnam. But the college deferment was still in place, which meant that no boys who grew up in my neighborhood were at risk of being shot at by those awful Viet Cong.

Teen culture had started to seep in with the Beach Boys. But the California world of surfing and woodies seemed as exotic to us as an Indonesian dance troupe on Ed Sullivan. Our one and only radio station, WEBC (AM of course), played Top 40 music in an indiscriminate scramble: on a 15-minute drive to the store, we would hear “Ballad of the Green Berets,” “Monday, Monday,” and “Born Free.” When the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together” came out, WEBC beeped out the title line every time, in the interest of public morality.

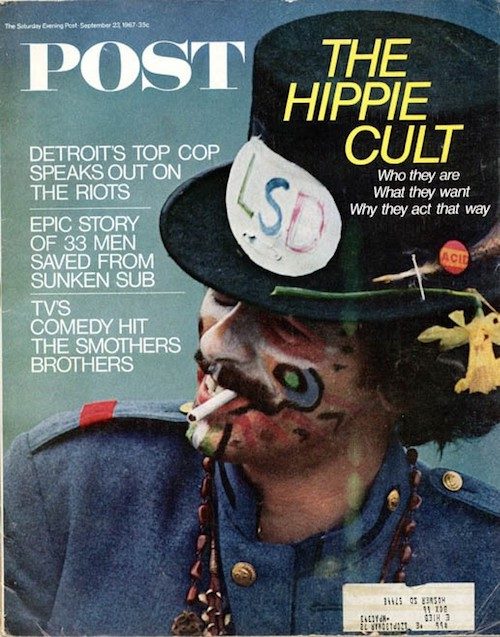

But cracks were opening up. Time and The Saturday Evening Post, which arrived weekly at our house, increased their coverage of civil rights and anti-war protests, and I began to tilt left. The TV shows Hullabaloo and Shindig! moved away from Petula Clark and Bobby Darrin and towards the Doors (sex!) and Jefferson Airplane (drugs!).

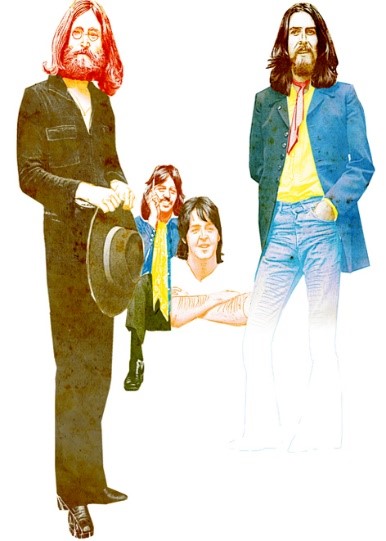

Drug culture took longer to reach us, too damn long as far as I was concerned. I had never succumbed to Beatlemania; the unwashed, sneering Rolling Stores were much more exciting. But it was mandatory that if you were between the ages of 13 and 21, you went gaga over the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I happily joined in, hoping that by listening to “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” I could get an aural contact high.

Somewhere, out in the real world, people were smoking marijuana and banana peels, ingesting morning glory seeds and LSD, expanding their consciousness in all kind of ways. But I was in a basement in International Falls, sitting around a tinny hi-fi system, with Sgt. Pepper on repeat and repeat, the record coming to a scratchy end and then flipped over, while the boy who lived there was dissolving Bayer aspirin in bottles of Coca-Cola, in an attempt to get himself and his pals, which included me but not my disapproving best friend, Wendy, high. We all claimed to feel something, although what I mostly felt was sick to my stomach.

I was huddled on that basement floor because that summer I was a long-term guest at Wendy’s grandma’s house. I had outgrown camp and the Northland Country Club pool. After the mandatory visit to Aberdeen, where I spent two weeks reading and sulking, my mother gratefully sent me north and out of her hair. International Falls was a small town, a lot like Aberdeen, but smellier, thanks to the paper mill. Wendy and I were regarded as sophisticated big city girls — “Wow, you live in Duluth!” —and welcomed everywhere. The day after the aspirin experiment, we were invited to a taffy pull at a neighbor’s, something I thought existed only in the pages of a Laura Ingalls Wilder book. My hands were buttered to the wrist, as if I were to be part of an adolescent orgy. The taffy was white and ropy and smelled of vanilla, and when finished was tooth-achingly sweet and tooth-shatteringly brittle. My father would have been horrified. I was annoyed at this wholesome party activity; I wanted to be back down in that basement, listening to records with boys and figuring out ways to get high.

I also participated in a bizarre experiment in reversing Down Syndrome. Wendy’s best friend before me had a baby sister with Down’s. I didn’t quite understand what was going on with this big-headed kid who couldn’t talk. The mom, searching for a cure, had fallen under the influence of a crack-pot theory that held that crawling was the basis of all subsequent learning. The mom spent hours manipulating her baby’s arms and legs in a swimming/crawling motion. When she got too tired she recruited anyone within shouting distance to take her place. I have no idea whether it helped or not. It was horribly creepy, moving the baby’s right arm and left leg for ten minutes, then switching to the left arm and right leg, while the kid made noises somewhere between a chortle and a howl. I hated going over to that house of sadness and madness.

The kid with the basement and the aspirin and the Sgt. Pepper’s album was International Fall’s leading Bad Boy. Wendy and I adored him. Several weeks into my visit, all of us 13-year-old aspiring juvenile delinquents were hanging out on a street corner, trying to be much cooler than we actually were. Bad Boy was smoking a cigarette (oooh!) and started lighting matches and tossing them into a red and blue mailbox. Of course, we found this, as everything Bad Boy did, hysterical. At about the twentieth match, smoke began seeping through the mailbox slot. All of us stood gazing horrified as the wisp became a serious plume, a “Yeah something is really burning” smoke signal. One of Bad Boy’s friends helpfully noted that we had probably committed a federal crime, setting the U.S. mail on fire. As the smoke darkened and streamed out of the mailbox, we fled in all four directions. Wendy and I bamboozled her poor grandma with some story about why we had to be back in Duluth immediately, and pooled our money for bus tickets, hoping to stay one step ahead of the law.

***

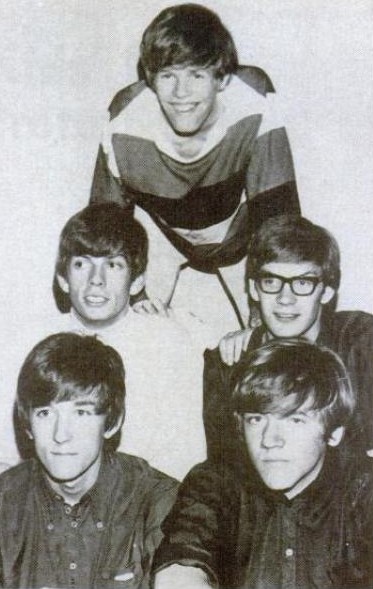

I got back to Duluth to find the entire teen universe abuzz. The Duluth auditorium, which had opened in 1966 and been home to hockey games, Ice Capades, and the Ringling Brothers Circus, was to have its first rock concert: Herman’s Hermits.

Wendy and I were speechless with joy. While Herman, aka Peter Noone, the lead singer, was almost a little too preciously adorable for my tastes (always a smile, never a sneer), he was undeniably cute. And I, like everyone under 25 in the country, had fallen under the perky, head-bobbing spell of “I’m Henry the Eighth, I Am,” which was played by the radio station at least once every hour, causing pre-teen girls to squeal, hop on one foot, and shout out “Second verse, same as the first!”

For weeks before the concert, I was lost in a whirl of daydreams where Peter Noone looked out in the audience, saw my adoring face, and fell madly in love. He would send someone out to escort me backstage, take me in his arms, kiss me, gently remove my clothes…and then stuff would happen that I was still having a difficult time imagining. I would get to that crucial point, sigh, and rewind my daydream back to the beginning.

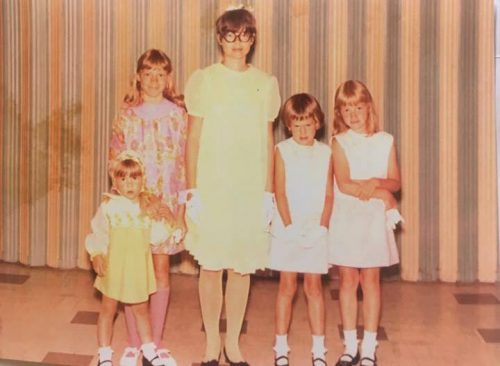

There was only one problem. I wore glasses, thick, hideous glasses which could kill the sex drive of any boy at ten paces. I could go to the concert without wearing my brown cat’s eye with sparkles (an improvement over the baby blue ones I had worn for years) but then I wouldn’t be able to see a thing onstage. How could I catch Peter Noone’s eye if he were just a fuzzy object? I wouldn’t even be able to tell him from the lesser, unnamed Hermits.

Shindig!, the TV music show, saved me. It was on during a school night, so Wendy and I had to watch it at our own homes, one ear glued to the phone, discussing which bands and boys we liked. Shindig! had a troupe of cute girl dancers (now there was a career!). One of these dancers wore, along with her mini skirts, Mondrian-inspired dresses, and go-go boots, a pair of perfectly round tortoise shell glasses. Thanks to some mysterious seismic movement or an alignment of the stars, a pair of those exact glasses showed up at my eye doctor’s, where before my choice had been between the baby blue or shit brown cat’s eyes with sparkles. My mother, the slave to fashion, was always delighted when I paid attention to what I wore and how I looked — which was still, with my badly cut mousy blonde hair, not good. But at least with my outrageously stylish new glasses, I commanded some attention from boys, most of it a startled reaction of “Weird.”

With my Shindig glasses and my own Mondrian color block mini dress, I was ready for Peter Noone to sweep me off my feet. I don’t remember what Wendy was wearing. It didn’t matter, she was only there to report back to all of Woodland Junior High that I was not in ninth grade because I had eloped with Herman.

My dad, who had been known to whistle “Henry the Eighth” himself occasionally, scored us seats a few rows from the stage. We had to sit through an opening act before Herman’s Hermits came on. That band was The Who. I had heard “I Can See for Miles” on WEBC a few times the winter before, enjoyed it, but relegated The Who to the category of British Bands I Kinda Liked: The Kinks, The Animals, The Zombies.

Seeing The Who live rocked my little Duluthian world. There I was, nicely dressed, waiting to see that sweet young man who politely told Mrs. Brown she had a lovely daughter. I got Roger Daltrey’s unhinged vocals (ooh, he was really cute!), Keith Moon’s spastic flailing over his drums, and Pete Townsend smashing his guitar on the stage floor over and over (and John Entwhistle noodling about in the background). The Who killed off any residual Minnesota nice girl in me and I was pitched head first into full-fledged Youth in Revolt. At the end of “I Can See for Miles” Townsend stomped offstage with the splintered neck of his guitar in hand while everyone around me politely applauded while muttering “Were they on drugs? What was that all about?” I knew what it was about, it was about smashing the old to make way for something completely new, whether the world or Duluth or Woodland Junior High was ready for it or not.

The crowd stood and roared when Herman’s Hermits took the stage; I was still in a daze; sorry Peter Noone, you are no longer my type.

North Country Girl: Chapter 17: Life in a Boy’s Dorm

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I never became one of the popular or cool girls at Woodland Junior High, although thanks to my shopaholic mother’s inability to stay out of department stores, I was voted Best Dressed. I was not doomed to friendlessness though; history repeated itself when I was scooped up by another pale blonde with an outré home life.

When I was in sixth grade, Congdon had offered weekly violin, viola, or cello lessons, complete with an instrument to take home, to any student who wanted them. (Someone must have noticed the complete lack of arts in the curriculum.) My mother pushed me to take violin, and I gave in, daydreaming of playing on stage, dressed in the figure-hugging black sequined dress, “Solo in the Spotlight” from my Barbie collection, accompanied by a very handsome man at a grand piano, although the image of a long-haired Bugs Bunny at the Steinway kept intruding. Every Wednesday, I brought my violin to school, lied to the saint of a violin teacher about how much I had practiced that week, and screeched out an unchanging set of scales and simple tunes.

At Woodland Junior High, seventh and eighth grade students were required to take a music class: orchestra, band, choir, or for the hopelessly tin-eared, music appreciation class, where I probably should have been. But my year of sawing out “Twinkle Twinkle” earned me a place in the last row of second violins, where I shared a music stand with Wendy Miller. We immediately bonded over our lowly status in Orchestra and our hatred of the teacher/conductor, Mr. Peleski, who constantly stopped in the middle of a piece, tapping his stand furiously with his baton, to single us out and with good reason. If Wendy and I were not ruining the music, we were hiding behind our music stand, whispering.

Like my old pal Becky Sweet, Wendy was a transplant, a rarity in a place where it seemed everyone grew up, went to school, got a job, married, and started their own families without ever leaving Duluth. People lived next door to their grandparents, or grew up in the same house their parents had been born in. Everyone knew everyone else (“Now do you mean the Andersons who live on Arrowhead Road or the Andersons who go to Sacred Heart?”) Meeting two girls in two years who were newcomers to Duluth was almost astronomically improbable.

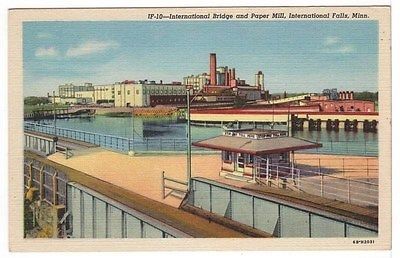

Wendy was from International Falls, a town known (even in the Icebox City, Duluth) as being way too cold, even though Wendy confessed to feeling a tingle of pride every time she saw Frostbite Falls on “Rocky and Bullwinkle.” International Falls was even better known for being permeated with the unholy stink from its huge paper factory, the reason for the town’s existence.

Wendy’s father had worked at this factory. That was all the information I ever got out of Wendy. I had been raised not to ask personal questions, and at twelve, I was too young to go immediately into the heat-seeking confessional mode with a new friend. Everyone had two parents, just like everyone had two arms and two legs. I would never ask anyone “What happened to your arm?” A misplaced parent was just too embarrassing to talk about, so I never knew whether Wendy’s father was dead or still back in International Falls, inhaling paper fumes.

Wendy’s mom was that rare creature I thought existed only on TV: a working mother. The two of them had moved to Duluth because Wendy’s mom had gotten a job as a dorm mother at the University. My new best friend lived in a boy’s dormitory.

How anybody thought it was a good idea to have a youngish, not unattractive single mom and her pre-teen daughter live with fifty eighteen-year-old guys, even in those days of innocence, is baffling.

The first week of school, I told my mother I was going the next afternoon to my new friend Wendy’s and her mother would drive me home. “Her mother works for the college,” I said, knowing instinctively to leave out her mother’s actual job title and the lack of a father.

Wendy and I lugged our textbooks and homework (no backpacks, and evidently we were all too stupid to even put our shit in a bag) up the hill from Woodland Junior High to the uninspired modern mediocrity that was the University of Minnesota Duluth campus. Most of the old gothic red stone buildings had been torn down and replaced by flat-topped white or red brick ones; the campus looked as if it were made of Legos. One of the long narrow buildings, which resembled a motel gone incognito, was the home of my new best friend.

Wendy and her mother lived in a tiny two-bedroom apartment at the front of the dorm. I was enchanted. It looked like my old Barbie Dream House! The couch was attached to the wall and the TV sat on a built-in shelf. The kitchen was just one side of the living room, with fridge, stove, and dishwasher, all slightly smaller than normal, lined up in a neat row. Wendy’s bedroom was just a bit wider than the space taken up by the two single beds. And there were boys everywhere: hanging around outside, cruising down the dorm halls, sprawled on the dorm mother’s sofa.

These spotty farm boys (most of the students in the dorms came from towns ever smaller than Duluth) were Olympians to Wendy and me, who looked upon even ninth grade boys as being as unobtainable as Illya Kuriakan or Napoleon Solo, our beau ideals from our favorite TV show, “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” (thankfully Wendy preferred Illya). These freshmen were a separate species, not boys, but not grown-ups either.

Not one of those college boys took any notice at all of the two glasses-wearing, flat-chested, giggly girls who were always around. If we had caught the eye of even the homeliest, most acned boy, things could have gone horribly wrong.

Wendy’s mom was required to be at the dorm almost all of the time, but her actual duties, other than sewing on a button, or giving instructions on the use of an iron, were non-existent. The freshman boys got up to nothing worse that drinking near-beer semi-secretively and smoking cigarettes openly in their rooms, but I guess the dorm mom was there to provide a semblance of adult supervision, locking up the front door at midnight (latecomers just rapped on dorm room windows till someone let them in).

The dorm boys all looked and acted pretty much the same. I kept learning their names and then immediately forgetting them. Except for one.

Let’s call him Joe. Joe was different because he had a drum kit in his dorm room. I never saw it as Wendy and I were strictly forbidden to go back into the boys’ rooms, or even into the hallway, but I imagine it as one big drum, one little, and two cymbals, a “My First Drum Kit.” Over and over, a vaguely familiar drum track with a six-count bang bang bang in the middle echoed down the dorm hallway. A few weeks into the school year, the dorm boys were saying that Joe was the drummer on “I Fought the Law.” The Bobby Fuller Band were not the Beatles or The Rolling Stones. I may have been able to find a photo of the Bobby Fuller Band in a teen fan magazine, if I ever bought one; even if the band had appeared on ”Hullabaloo” or “Shindig!” the camera would never have lingered on the drummer. Joe could be the drummer for Gary and the Pacemakers, for all we knew; after all, he did have drums.

A few days later Wendy gave me the news that Joe had admitted that he was the drummer on “I Fought the Law,” wowing everyone on campus. Someone famous was in Duluth and we knew him! Rosy-faced girls began to hang around outside the dorm, gloved hands shoved in coat pockets, necks craned, hoping for a glimpse of the rock ‘n’ roll guy. He gave an interview to the “Bulldog,” the UMD newspaper, about his other life as a member of a band, when he wasn’t studying plant biology or geography. Alongside the interview ran his photo, sticks in the air as ready as a sixgun.

Then Joe cracked. He contacted Channel 6, one of our three TV stations, told them that he was the drummer for the Bobby Fuller Band, and offered to play his drums live on their station. At the appointed times, I sat cross-egged in front of my television, thrilled by my brush with fame. Our kitchen phone cord was stretched from a coil to a taut line, so Wendy and I could talk; she told me there were so many guys smashed around the TV in her living room you couldn’t move. A voice announced, “Ladies and gentleman, Joe from the Bobby Fuller Band!” The camera turned on Joe, in black and white, sweating and shaking. There were no drums. Joe stammered out that he had to come clean. He wasn’t the drummer from The Bobby Fuller Band. He had made it all up. He just really, really, liked that song.

Wendy had hung up from her end. I turned off the TV and walked away and never saw Joe again.

My former best friend, Becky Sweet, was obsessed with George Harrison and sex; I don’t think she knew the name of a single boy in our sixth grade class. My new best friend, Wendy, was obsessed with boys and getting a boyfriend. I was twelve, a year younger than Wendy, but my own hormones were starting to percolate. I was literally fertile grounds. Whenever I found even a slightly suggestive scene in a book, I would read it over and over again, imagining myself as the character, whether her clothes were being gently removed or if she was being gang-raped. I relied on books, my oldest and best friends, to tell me about sex, which seemed equally horrifying and thrilling. I wondered, what did it feel like to have a boy touch your breast? What did a penis actually look like? And most important, why didn’t any of my books tell me how to get a boy to like you?

Wendy was convinced that the first steps to winning a boyfriend were cute clothes and lip gloss. My mother, who would have picked out clothes for a potted cactus, agreed. Mom was thrilled that I was finally taking an interest in what she bought for me, instead of sulking while she pawed through dresses in Glass Block’s Junior Department, hoping we would get ice cream at Bridgeman’s when this ordeal was over, while Lani ran amok in the store, knocking down racks of clothing.

I still hadn’t gotten through my straight-A-student brain that seventh grade boys had no appreciation for teen fashion. Wendy and I and our cute clothes held zero appeal for them. But I found almost all of the boys fascinating. They were new. I hadn’t spent years in elementary school with them. I had never seen them pick their nose and eat it, or cheat on a spelling test. These boys hadn’t pushed me off a swing or thrown a dodgeball right at my face.

Some of these Woodland boys were mini-hoodlums, who got into daily after-school fights at “The Hill,” a grassy mound behind the parking lot, fights that were pointedly ignored by teachers headed for their cars. I lurked at the farthest back of the crowd, not knowing the contestants or their beefs. These fights were usually shoving and name-calling, and ended in minutes with a split lip, bloody nose, or black eye. Girls either followed the winner or tried to console the loser. I would file away the new curse words I learned and head over to Wendy’s to lie about how close I had been to the fight.

Some of these boys were jocks in the making, playing all four junior varsity sports and growing muscles and confidence. Groups of jocks always hovered around the popular girls’ table in the cafeteria, a table ruled over by Colleen Finuchin. Wendy and I could do nothing but look on with awe. Every few weeks, Colleen would invite some girl who was not a member of her clique to sit at her table. The poor sap would be so happy, surrounded by cute boys, soaking in popularity. Until the inevitable day would arise: the sap would show up at Colleen’s table, lunch tray in hand, and find her spot taken by a new grinning sucker. “Sorry, there’s no room,” Colleen would say, and turn to whisper something in her new best friend’s ear while the exile turned red and trembled before turning away in shame, wondering what sin she had committed to be banished. Wendy and I were so low in seventh grade status that we were never invited to sit at Colleen’s table. I like to think that we would have been smart enough to say no.

The clutch of smart, nerdy boys was the only pool where I had a chance of fishing for a boyfriend. I had an entrée into this group: there were a few boys I knew from that wonderful fifth grade enrichment program. They squinted at me and said, “Oh yeah. Gay. You read that Greek myth wrapped in a bed sheet.” I could talk to Bart Schneider or Tom Hoff without feeling that I needed to pee, but neither they nor any of their geeky pals asked me to a junior high afternoon football game or offered to buy me a sundae at Bridgeman’s,