How McCloud Reinvented the Wheel for TV

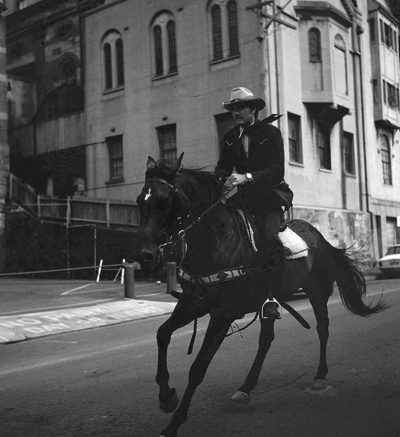

Some actors’ lives are just as colorful off-screen as on. Take Dennis Weaver, who was a Navy fighter pilot in World War II, an Olympic hopeful in decathlon, and an environmental activist. In front of the camera, he starred in Steven Spielberg’s first film, did nine years as sidekick Chester on Gunsmoke, and helped usher the cowboy hero into 1970s New York 50 years ago this week with McCloud. That fish-out-of-water cop show didn’t just lay the groundwork for later shows like Due North and Justified; it helped pioneer a format that allowed the network to introduce multiple shows in one timeslot, a plan that would usher in more than one TV classic.

McCloud debuted with a TV movie pilot on February 17, 1970. The premise had Deputy Marshal Sam McCloud (Weaver) escort a prisoner from his normal base in New Mexico to New York City. McCloud would be embroiled in solving a murder case, and thereafter end up on loan to the NYPD as a special investigator. That basic plot had its roots in the 1968 Clint Eastwood film, Coogan’s Bluff; Herman Miller, who wrote the story for Bluff, is credited as McCloud’s creator. Response to the pilot was strong enough that McCloud was selected as one of four programs for NBC’s Four in One.

The Four in One concept put four different shows in one timeslot as part of a “wheel” of programming. This was similar to other NBC “wheels” like The Name of the Game (which had three rotating stars) and The Bold Ones (which was built around four profession-based procedurals). McCloud was first at-bat, running six episodes through September and October of 1970. New series San Francisco International Airport was next, followed by Rod Serling’s successor to The Twilight Zone, Night Gallery, with The Psychiatrist taking the fourth slot. Like McCloud, Night Gallery had a well-received pilot before joining the rotation; those two series were chosen to continue after the Four in One experiment, while SFIA and The Psychiatrist were cancelled. Gallery went on to its own solo slot, while McCloud joined another wheel.

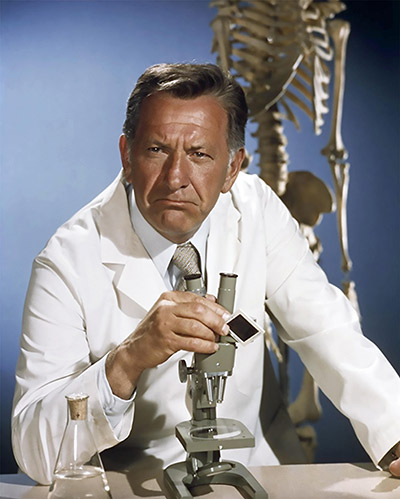

This new wheel, The NBC Mystery Movies, would become the home for other iconic shows. In addition to McCloud, the first season included Columbo (which had been tested in a 1968 TV movie) and McMillan & Wife. The setup turned out to be a strong draw for the network, with all three shows running several seasons. The network liked the concept enough to add a second mystery movie night on the schedule, Wednesdays; of those various series, the breakout hit was Quincy, M.E., which eventually spun off into its own one-hour slot for many years.

McCloud itself lasted seven seasons, though the total episode count is lower than a typical series because of the movie format. Weaver and other members of the cast reunited for The Return of Sam McCloud, a 1989 TV film. Weaver continued acting for the rest of his life, and was a regular on the ABC Family series Wildfire just prior to his death in 2006.

While it’s not an official brand on today’s networks, the wheel concept is still in effect in subtle ways. ABC did directly revive the concept in 1989, going so far as to bring back Columbo. A more modern take would be how a number of reality-competition series share timeslots or dovetail their runs, such as The Bachelor and The Bachelorette or Survivor and Big Brother. Other similar ideas include devoting one entire night of programming to related shows, such as NBC’s “One Chicago” concept, where Wednesday nights feature three shows (Chicago Med, Chicago Fire, Chicago P.D.) set in the same fictional universe. Another influence is the idea of putting more capital into smaller numbers of episodes, a practice also influenced by British TV and adopted at pay-networks and streaming platforms to great success. McCloud may have been an old-fashioned western in modern clothes, but it ushered in a new way of thinking about television.

Featured image : Copyright © Globe Photos/ZUMAPRESS.com / Alamy

How Hopalong Cassidy Brought the Western to Television

It’s not unusual for a character from novels and short stories to make the jump to film or television. In fact, so-called transmedia properties are extremely common today, with comics designed to be films or TV shows that get adapted into long-running series of books. However, it’s not every day that a character crosses over, and brings an entire genre with them. That was the case on June 24, 1949, when Hopalong Cassidy made the jump from books and movies to the small screen, kicking off the legacy of the Western on television.

Hopalong wasn’t new in 1949. The character first appeared in the writings of Clarence E. Mulford. He created the character in 1904, and the first book to feature Hopalong, Bar-20, saw publication in 1906. The original version of Hopalong was considerably more of a rude character than he would be onscreen; he also owed his nickname to a wooden leg. By the time that he became the title character of 1910’s Hopalong Cassidy, the cowboy already had a strong following.

Some of Cassidy’s rougher edges where smoothed when he made the transition to the big screen in 1935. Actor William Boyd took on the role, and the character became a bastion of fair play. Perhaps as a nod to his more dangerous literary persona, Cassidy (who earned his nickname from a gunshot-induced limp rather that a wooden leg) wore all black, including his hat, a departure when most good guys were clad in light colors and white hats. The first film, Hop-Along Cassidy (the inexplicable hyphen was dropped later), took elements from the books but wasn’t a slavish adaptation. Boyd would play Cassidy an astonishing 66 times between 1935 and 1948, with ten different sidekicks accompanying him throughout the films.

Producer Harry Sherman had grown tired of the films by 1944. Boyd took the unusually step of buying the right to the character from Mulford and the previously produced films from Sherman. By 1948, Boyd had a new idea. He took the films to NBC for broadcast; 52 of the movies were edited down to episode length for a Hopalong Cassidy TV series. The first episode, “Sunset Trail,” ran on June 24, 1949.

The young medium proved to be a perfect fit for Boyd and his character. Cassidy’s popularity went through the roof, with the show beloved by kids and adults alike. The remaining 12 films were edited for a second season, and Boyd put together a company to make new episodes (which also featured Edgar Buchanan as new sidekick Red Connors). The edited movies comprised the first two seasons, and the 40 new shows completed two more seasons through 1955. During that same period, Boyd starred in a radio drama version of the show that ran for 105 installments. With the films, TV, and radio (as well as an ongoing comic strip) behind him, Boyd became a massive celebrity, covered by magazines and touring the world.

When he finally retired in his sixties after 20 years of playing the character, Boyd’s primary reluctance at saying good-bye to the show was the employment of his production team and crew. By a stroke of luck, CBS was putting together the TV adaptation of another popular Western radio program. Boyd kept his crew employed by putting them to work at CBS on the new show. It was called Gunsmoke, and it would run for 20 years.

Hopalong Cassidy presaged the dominance that Westerns would display at both the movies and on television throughout the 1950s. While many of the early shows, like Cassidy, were child-friendly, Gunsmoke and its immediate prime-time antecedent, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, were directed at more adult audiences. Those programs led a Western expansion that saw more than 30 of the shows on the air by the end of the decade, with eight of the top ten shows in March of 1959 being Westerns. In the theaters, approximately 700 Westerns were released between 1950 and 1959.

Critics and scholars continue to debate what caused the decline of the Western. While the form was still popular in the 1960s, it wasn’t as pervasive. Pressure groups decried the violence present in some Westerns, while others were affected by general fatigue with the genre. The Space Race kicked off an interest in science fiction programming that, coupled with the rise of color TV, saw “space shows” replace “horse shows.” There was also a shift in the 1960s to programs set in both urban settings and contemporary times, both of which left the Western behind.

The Western itself has never completely left television, and it likely never will. Today, programs like Kevin Costner’s Yellowstone still run on outlets like the Paramount Network, while the general influence of the Western is seen in a variety of diverse 2000s shows like Justified, Hell on Wheels, and the genre-bending science-fiction of Westworld. The general appeal of the genre has never been in question; it relies on the idea of open ranges, the possibility of a bright future, and the notion that the proper person riding in on a good horse can make things right. The dream of the West might be a dream, but at least it’s a good one.

True Grit vs. The Wild Bunch: The Week of Peak Western

They opened one week apart 50 years ago. One featured the matchless giant of the genre; the other came from one of its great directors. True Grit opened first, followed just seven days later by The Wild Bunch. These two films reflected different views of the Western, but also proved how versatile and durable the form could be in the right hands.

Charles Portis’s True Grit first saw light as a novel serialized in The Saturday Evening Post in 1968; the following year, it was adapted into a screenplay by Marguerite Roberts. John Wayne had campaigned for the lead role of Rooster Cogburn after reading the book, and championed Roberts as a writer despite her having been “blacklisted” during the Red Scare. Wayne would later recall the script as the best he’d ever read.

Wayne, of course, typified the Western genre in the American consciousness. Of the approximately 170 films he appeared in, over 80 of them were Westerns. Wayne was conservative politically and curated his reputation to the point where he declined to appear in the Western comedy film Blazing Saddles because he felt that the raunchy material went against his family-friendly image. That image actually made a for a good fit with the material of Grit, where Wayne’s cantankerous U.S. marshal develops a vaguely paternal relationship with young Mattie (played by Kim Darby), who hires him to track down her father’s killer.

The original trailer for True Grit (Uploaded to YouTube by Paramount Movies)

Despite pushing against the boundaries of the traditional Western by highlighting the fact that Cogburn is an aging protagonist, much of the plot fits within the confines of what people were expecting of the genre and Wayne. The curmudgeonly Cogburn is a decent and heroic man, as is the third member of his and Mattie’s group, Texas Ranger Le Boeuf (country star and occasional Beach Boy substitute Glen Campbell). Justice is served, evil is punished, and Mattie even promises to have Cogburn interred at her family plot when he dies. The film traffics in themes of “found family” as much as it does in the well-worn revenge and justice tropes of the Old West.

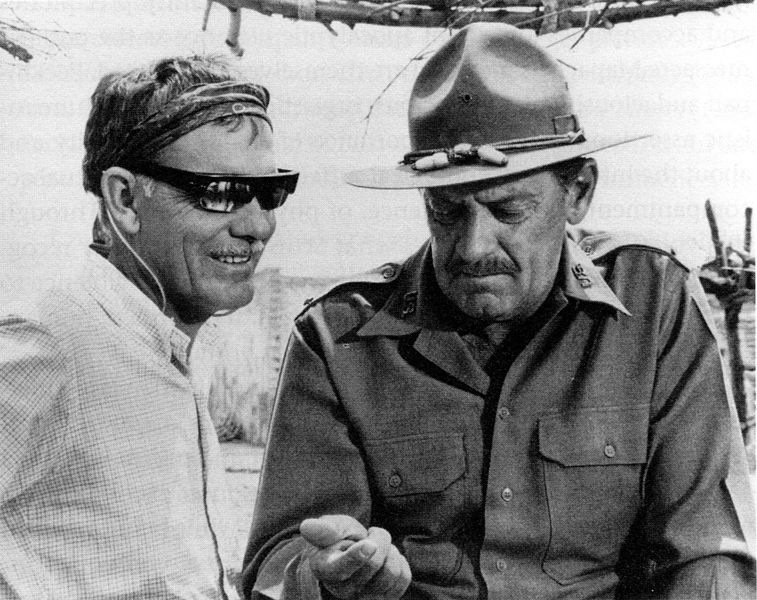

Released just one week later on June 18, 1969, The Wild Bunch leans into a very different sensibility. Directed by Sam Peckinpah, who rewrote the film from an original screenplay by Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner, The Wild Bunch captures the same ethos of the aging cowboy, but flips it from lawman to outlaw. The film taps into the idea of “honor among thieves,” challenging the audience to identify with a cast of hardened criminals while suggesting that they do indeed adhere to their own version of a code.

The original trailer for The Wild Bunch (Uploaded to YouTube by Warner Bros.)

The overall plot of The Wild Bunch, which involves a group of outlaws (led by William Holden and Ernest Borgnine) chasing their last score, isn’t that unusual. Neither is the subplot of the group being pursued by a now-deputized former ally (played by Robert Ryan). What sets the story apart is the way in which the steady approach of the modern world is transforming the West. The characters are aging, and the country they knew is changing around them; they recognize their own mortality and the fact that they are, in a sense, outdated characters.

But the larger, and more shockingly revolutionary change, is the frank depiction of violence. Peckinpah leans into the brutality. His shoot-outs pull no punches. They are bloody, messy affairs that strip away the lie of the clean gunfights that filled earlier movies of the type. Civilians, including women and children, die in public crossfires. Bodies are riddled with bullets. And the blood doesn’t just flow; it bursts. This is the same frank depiction of violence that began in part with Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 and continued throughout Peckinpah’s own work, including Straw Dogs and Cross of Iron, signaling the beginning of what was called “the new Hollywood,” which placed a greater emphasis on realism and cinema as visceral experience.

The two films met with very different receptions. Wayne won both the Golden Globe and Academy Award for best actor for True Grit, while the title song (sung by Glen Campbell) was nominated for both distinctions, as well. The movie turned out to be a solid box-office performer, as well.

The Wild Bunch was instantly polarizing; the late critic Roger Ebert recalled that, at the initial screening, he stood to defend the film against an attack from the critic for Reader’s Digest, who had questioned why such a film had even been made. A number of prominent critics did praise The Wild Bunch, including Vincent Canby of The New York Times; Time also weighed in with positive notices, offering unabashed praise of Holden and Ryan and going on to state that “[the film’s] accomplishments are more than sufficient to confirm that Peckinpah, along with Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Penn, belongs with the best of the newer generation of American filmmakers.”

One person that wasn’t a fan of The Wild Bunch was, perhaps unsurprisingly, John Wayne. Wayne noted privately and in interviews that he felt that that film destroyed the myth of the Old West. The actor commented on Clint Eastwood’s similarly nihilistic High Plains Drifter in 1973; in a 1993 interview with Premiere magazine, Eastwood recalled that Wayne wrote him directly and said, “That isn’t what the West was all about. That isn’t the American people who settled this country.”

Over the years, True Grit continued to be held in high esteem, while The Wild Bunch grew in reputation among critics and film scholars. Peckinpah’s command of violent action and quick editing can be seen today in the work of directors like John Woo and Quentin Tarantino. True Grit received an acclaimed remake in 2010, while The Wild Bunch has managed to avoid multiple efforts at a new version. It’s fair to say that Bunch helped usher in the age of the revisionist Western, seen in films like Unforgiven that take a more unflinching look at consequence of violence. It’s perhaps strange that two genre classics that were so different from one another were released in the same week, but it did seem to mark a tidal shift when the narratives of American film grew darker and the myth of the American West began to be resigned to just that: a myth.