The World War II Conference that Altered the Outcome of History

75 years ago, at the height of World War II, the leaders of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union came together for the first time. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Premier Joseph Stalin each knew that agreements and concessions had to be made, particularly toward Stalin’s strong desire to open a second front against the Axis powers in Europe. The four-day conference resulted in plans that would be crucial to the winning the war and to shaping the post-war world. Here are five ways that this historic gathering altered the outcome of history.

1. Together, for the First Time

While Churchill had met previously with FDR seven times across two continents and with Stalin twice in Moscow, the three men had never been in the same place at the same time prior to November 28, 1943, the first day of the summit. In fact, FDR and Stalin had never met at all until Stalin greeted FDR at the first meeting. Churchill arrived a half-hour later. The historic gathering not only got the leaders on the same page, but also set the stage for further important conferences in Yalta and Potsdam.

Footage of the Cairo and Tehran Conferences from the FDR Presidential Library.

2. The Hard Part Was the Easy Part

Stalin’s main objective was to get the others to open a second front against the Axis in western continental Europe. He’d been trying to persuade Churchill on this since 1941, but Churchill knew that it would have been hard to do with the Mediterranean and northern Africa in play. However, FDR told Stalin early in the conference that he intended to set a target date to open a second front with a mainland invasion of France in May of 1944.That invasion,code-named Operation Overlord, or, as it became known, D-Day, would ultimately be carried out on June 6. Stalin, knowing that his long-desired second front was in the works, also assented the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan as soon as Germany was beaten.

3. The Birth of the United Nations Was Assured

The League of Nations hadn’t been properly functional in years, and had done nothing concrete to prevent several crises, including the German expansionism that was a forerunner to World War II. In 1941, FDR, Churchill, and FDR’s aide Harry Hopkins created a “Declaration of the United Nations.” The United Nations was FDR’s term for the Allies. The document mentions “Four Policemen,” which were the major Allied powers of the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China. By January 2, 1942, representatives of 26 different countries had signed it. At the Tehran conference, FDR addressed the idea to Stalin directly, positing that there needed to be a consistent organization to try to resolve issues and prevent global warfare. All three leaders agreed that they needed to pursue the principle after the war. Conferences and meetings continued to further the project until the first official meeting of the U.N. General Assembly in 1946.

4. They Got Other Countries Involved

Turkey had continued to have relations with Germany into the war, but had promised enter the war on the side of the Allies when the country was more prepared. At the conference, Stalin pledged to aid Turkey if Germany or Bulgaria attacked. By 1944, Turkey broke off their relations with Germany and formally declared war on Germany and Japan early in 1945. While the length of time it took Turkey to get involved was seen by many as a more ceremonial or symbolic decision, it did pave the way for Turkey to join the United Nations and, later, NATO in 1952.

The three leaders also agreed to offer aid to partisans in Yugoslavia who were fighting the Axis in their country. Allied air support and Soviet troops on the ground bolstered the resistance and enabled the Yugoslavian troops to drive back the Axis. Many scholars refer to the Battle of Poljana in May of 1945 as the last battle of World War II in Europe.

Other major moves included Churchill and Stalin discussing a change to Poland’s borders. FDR abstained from the conversation as he didn’t want to alienate Polish-American voters at home. On the other hand, FDR did encourage Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to be reincorporated into the Soviet Union if the citizens of those countries voted for it.

5. Germany Would Be Divided

Though this would obviously cause many problems later, the powers agreed to an initial idea of dividing a post-war Germany. The theory was that as the driving force behind two world wars, a divided Germany would be less able to precipitate another global conflict. The ultimate result was that the divided Germany became a pivotal location in the later Cold War between East and West until its reunification in 1990.

John Lithgow Shares the Secret of Playing Churchill in Netflix’s ‘The Crown’

When I heard that John Lithgow was cast to play Winston Churchill in the new Netflix series, “The Crown,” I had to wonder. Lithgow as the legendary Prime Minister? The short and rotund Sir Winston hardly resembles the tall, slim Lithgow. The show, written by Peter Morgan, who also wrote “The Queen,” is a serious drama about the royal family and I knew he wouldn’t entrust the role to an American actor on a whim. Then I watched John on screen. He’s properly paunchy thanks to some padding under that waistcoat. Add a dead-on English accent and a stubby cigar clenched between his teeth, and it’s an amazing transformation. I got to congratulate John personally. He towers over me and had to lean down to give me a kiss on the cheek. As he bent way over I said, “Ok, you are more than a foot taller than Churchill – How did you handle that?” His eyes twinkled and he replied, “I relied on a special acting technique. I just kept telling myself, think short!”

Jeanne Wolf: You’ve often said that your life is a lot of lucky happenstance. How much does luck play into your life and how much does all your hard work, your talent?

John Lithgow: Well, luck plays into it of course. Actors just never know what’s coming along. You depend so much on bright ideas that other people have for you because very often they think of things you would never think of yourself. I would never cast myself as Winston Churchill but when Steven Daldry cast me as Winston Churchill, I couldn’t say yes fast enough.

JW: Fears and all?

JL: I trusted him. He’s a director that I’ve always wanted to work with. I knew Peter Morgan created the series. I just figured, “Well, if you want me, I may be scared of this but I’m certainly not gonna say no.”

JW: I have to know at which point you looked in the mirror and said, “Why did I ever say yes to this? What am I doing? How do I pull this off?”

JL: You know, in my career, I am fortified by the fact that the work that I’ve done that has been most satisfying to me, I have been scared to do. It was other people’s bright ideas that kind of took me aback. I went over to England and started working with the actors of “The Crown,” none of whom seemed to have the slightest problem with an American playing Winston Churchill, much to my surprise. My confidence grew and grew and grew. I collaborated with all these wonderful people—costume and makeup and dialect coaches—in every area.

JW: Did you have a cigar coach?

JL: I needed no coaching with the cigar. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to smoke good cigars. Just like in America, you’re only allowed to smoke these kind of dreadful, vegetable cigars on set, but I made it look like I enjoyed it.

JW: Yes you did. You know, as the series begins, we don’t get a picture of him that reminds us of the statesman that we all have idealized. Even his colleagues think they’re going to take over for him. Do you think that’s part of his trick that he didn’t let everyone see what he was seeing or see what he knew?

JL: Well that’s an interesting question. I think Churchill was so completely himself to a fault. He hadn’t the slightest problem with offending people or making enemies. He had a sort of reckless courage about his own convictions. It’s what made him incredibly unpopular until he became incredibly popular and his whole career was made up of those highs and lows and it was usually his bulldog personality which accounted for both.

JW: Did he know that they were practically making fun of him and trying to get him kicked out? Did he sense that? Was he enjoying it?

JL: I think both. I think he was threatened and I think his response is to fight back. He was a man with tremendous insecurities, a propensity for depression, and a sense of constant impending defeat and yet he fought back in all sorts of ways – and fascinating ways! He fought off depression by sitting outdoors and painting landscapes. He was a man full of conflicts, contradictions, and colors.

JW: Let’s talk about the moment where he has to speak to the radio audience and tell about the king being dead and all of a sudden, he looks different and sounds different. You understand what they meant for charisma with this strange guy and you understood how he commanded the room and the nation. Can you talk about his genius and can I use the word ‘charisma?’

JL: Of course! I think that’s wonderful that you took that away because it was certainly our intention. This was a man who was destroyed with grief at the loss of the king and fear of whether or not the monarchy would survive and he knew that if he failed in that speech on the radio then he was a goner. He knew that his rivals in the Tory party were counting on him to do a bad job. He did a magnificent job and I think it is that wonderful duality – a man who appears so defeated and so frail and incompetent suddenly being so much more than competent.

There’s something about British royalty, say what you like about the whole idea of a monarchy in the modern day, it’s got some sort of mysterious importance to the whole British experience. That’s why it makes such incredible drama. You can’t quite define what that importance is but you know the stakes are very high. Can this young girl be a queen at a moment when British society is in economic rubble post war? Do they really need a queen? Half of them don’t want it anymore. Churchill believed so fervently that they have got to have a strong sovereign. He’s the only Victorian left standing and he takes it upon himself to turn her into a great queen.

–Jeanne Wolf is our West Coast Editor

‘Never Give In’

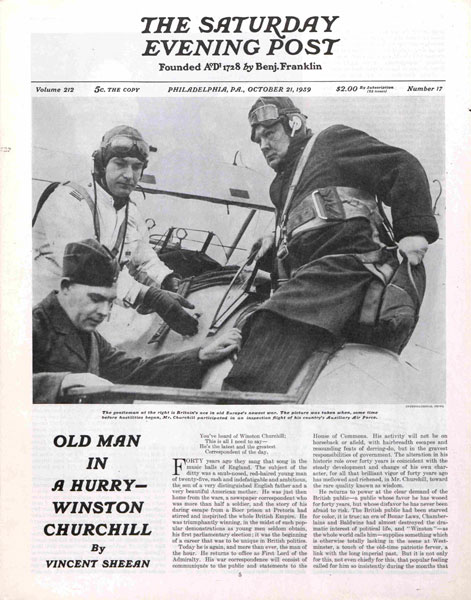

respect as well as affection for Churchill, as this camera study shows.

Britain’s best news of 1939 came just three days after the start of war. The news was so good, the British Admiralty ordered it to be sent to every ship in the fleet. It came as just three simple words that were filled with hope: “Winston is back.”

The news confirmed the rumors that Winston Churchill had been brought back into the government as the First Lord of the Admiralty, the post he’d held in World War I. His return to government marked a hopeful change of direction. Great Britain had steadily been losing ground before Hitler. Now, with war declared, the country needed a tough and relentless fighter. And that was Winston.

It seems he had always been “Winston.” As journalist Vincent Sheehan wrote of the man, “Today, when he is 65, they still, duchesses and taxi drivers, call him ‘Winston,’ just as they did when he was 25.” (Read the entire article “Old Man in a Hurry- Winston Churchill” by Vincent Sheean from the October 21, 1939 issue of the Post.)

Winston’s name had been popping up for years in the Post, as well as its sister publication. As far back as November 23, 1899, The Country Gentleman ran a brief update on England’s war against the South Africans. A detachment of British soldiers. it said, had been sent to rescue the besieged garrison at Ladysmith:

“These troops unfortunately attempted to ride in an armored train, with disastrous consequences. Encountering a party of Boers north of Frère, they began to withdraw. While retiring, some of the trucks were derailed … a company of Dublin Fusiliers … turned out and advanced toward the enemy, while the rest of the train appears to have returned without them to Estcourt. It is believed that these men were taken prisoners, 100 in number, including Winston Churchill, son of Lord Randolph Churchill, who was acting as correspondent, but who assisted actively in the fighting.” (Of course he was in the fight; Churchill was forever looking for opportunities to distinguish himself.)

No one, including Winston himself, could have known that his capture was the beginning of a long, remarkable public career. After only a month in a Boer POW camp in Pretoria, he escaped and returned to British lines. At the time, the war had been going badly for Great Britain and Churchill’s escape made him a popular hero. It boosted his career as a correspondent and, shortly afterward, as a politician.

Take our quiz: Did Winston Churchill Really Say That?

By 1912, he was an experienced, successful, and highly confident politician. A Post editor described him as a man of “charming impudence,” though admitted his opponents viewed this quality as “insufferable insolence.”

“In his early days in politics he took none of the stodgy political pretensions of the older statesmen seriously, but flouted them, laughed at them, was insolent, impudent, satirical, sarcastic, by turns. He would break a lance with any of them, and had no reverence for age, reputation, or awe of convention and precedent.” (Read the entire article “Who’s Who- and Why” from the December 7, 1912 issue of the Post)

According to the author, Churchill lived in his own special world. “His sunsets are always more beautiful, his sunrises more glorious, his dangers more vivid, his pleasures more pronounced, than those of any other. As he looks at it, the sunset is his personal perquisite, and the sun always rises for his especial benefit.

“The only American to whom he can be compared,” the author continued, “is Theodore Roosevelt; and that comparison isn’t especially apt, for Churchill writes far better than Roosevelt does, talks far better, and at thirty-eight has gone farther than Roosevelt had when he reached that age. Of course Churchill never can be king, and Roosevelt has been president; but Churchill will undoubtedly be a Prime Minister of England one of these days.”

The Post’s prediction came true, but not for another 28 years. And for much of that time, there were many—Churchill included—who believed he had lost any hope of ever becoming Prime Minister.

Early in the 1930s, he had argued with his party about granting self-government for the British colony of India. Then, in 1936, he urged King Edward VIII not to resign in order to marry American divorcée Wallis Simpson. When he publicly stated that the government was pressuring Edward to abdicate, his party turned against him. He was banished from the inner circles and soon lost much of his public support.

His political exile, which lasted for years, proved to be a challenge similar to Franklin Roosevelt’s polio; it increased the man’s resiliency and determination. And during his years on the outside, he continually spoke out against appeasing Germany. He repeated that Hitler couldn’t be trusted, and that abandoning Czechoslovakia to the Germans would only delay war, not buy peace.

And by 1939, Sheehan, among others, was writing about the hero’s return:

“He returns to power at the clear demand of the British public—a public whose favor he has wooed for 40 years, but whose disfavor he has never been afraid to risk. … It is a strange turn of the irony of circumstance that Winston, who was for so many years ‘too clever to be trusted,’ is now the man whom the whole Empire trusts to preserve it. …

“At first, I, like most others who have come near him, was frankly afraid. His personality is an army with banners; your first impulse is to get out of his way. His slightest sentence has weight because the words seem chosen from an altogether exceptional arsenal of words with altogether exceptional care. He has a huge vocabulary and no hesitation in using it according to the dictates of his own instinct and experience. This sometimes means a flood of words, sometimes the merest laconic, summing up, but there is never a word thrown away, meaningless.

“In all these respects, as well as in the more important ones, ‘Winston’ stands in the sharpest contrast to his protagonist in this war, the fanatical, teetotaler, vegetarian, neurotic Adolf Hitler. One is a rounded man—in more senses than one—who enjoys life to the full and wishes to preserve its freedom and variety for his people; the other is a haunted shell of a creature who would immolate the whole universe, if need be, to his adolescent dreams of revenge and fulfillment.”

By this time, Churchill was already pushing the British government to take action in Scandinavia. He realized that Great Britain needed to secure the mines and ports in Norway and Sweden that supplied its iron, but Prime Minister Chamberlain hesitated and took no action until April 1940, after Hitler invaded Norway.

The following month Chamberlain resigned. Churchill became prime minister just as Hitler began his sweep across Europe, conquering France, Britain’s chief ally. By the month’s end, nearly a half million British soldiers were clinging precariously to the Belgian coast, surrounded by the German army. They were alone, outnumbered, and outgunned. But they had Winston.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: